Religion and the New Atheism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex-Google Engineer Starts Religion That Worships Artificial Intelligence

Toggle navigation Search Patheos Beliefs Buddhist Christian Catholic Evangelical Mormon Progressive Hindu Jewish Muslim Nonreligious Pagan Spirituality Topics Politics Red Politics Blue Entertainment Book Club Family and Relationships More Topics Trending Now Spiritual but Not Religious Should Be... Guest Contributor Redefining Pro-Life Guest Contributor Columnists Religion Library Research Tools Preachers Teacher Resources Comparison Lens Anglican/Episcopalian Baha'i Baptist Buddhism Christianity Confucianism Eastern Orthodoxy Hinduism Holiness and Pentecostal ISKCON Islam Judaism Lutheran Methodist Mormonism New Age Paganism Presbyterian and Reformed Protestantism Roman Catholic Scientology Shi'a Islam Sikhism Sufism Sunni Islam Taoism Zen see all religions newsletters More Features Top 10 Things Never to Say to Your... Leah D. Schade We Must Root Out All Forms of Racism Henry Karlson Key Voices Is God Using Natural Disasters As A... Jack Wellman What Pianists Know pleithart Toggle navigation Home Ask Richard Podcasts Speaking Contributors Media Contact/Submissions Books Nonreligious Ex-Google Engineer Starts Religion that Worships Artificial Intelligence September 29, 2017 by David G. McAfee 111 Comments 1786 Anthony Levandowski, the multi-millionaire engineer who once led Google’s self-driving car program, has founded a religious organization to “develop and promote the realization of a Godhead based on Artificial Intelligence.” Levandowski created The Way of the Future in 2015, but it was unreported until now. He serves as the CEO -

Students Blaspheme Hosted a Discussion on the Importance of Taking Personal Moral Responsibility for the Planet Wednesday Night in the Memorial Union

Iowa State Daily, October 2010 Iowa State Daily, 2010 10-2010 Iowa State Daily (October 1, 2010) Iowa State Daily Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2010-10 Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Iowa State Daily, "Iowa State Daily (October 1, 2010)" (2010). Iowa State Daily, October 2010. 6. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2010-10/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State Daily, 2010 at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State Daily, October 2010 by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sports Opinion Your weekend previews, Video games level-up, ready for consumption assist scientific endeavors p8 >> p6 >> FRIDAY October 1, 2010 | Volume 206 | Number 28 | 40 cents | iowastatedaily.com | An independent newspaper serving Iowa State since 1890. Campus First Amendment Weekend allows families to learn about student life By Molly.Collins and Sarah.Binder iowastatedaily.com The events planned for Cyclone Family Weekend, start- ing Friday, will provide ISU students the opportunity to bring their families to their new home and let them have a taste of life as a Cyclone. Families will get to explore campus, dis- cover what Iowa State has to offer and spend time with their Cyclone students. “One thing I’m looking forward to is having my parents see how everything goes up here, so that way they get a feel for what I’ve been doing,” said JP McKinney, freshman in soft- ware engineering. -

2018-Photo-Calendar-FINAL.Pdf

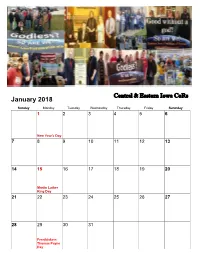

Central & Eastern Iowa CoRs January 2018 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 New Year's Day 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Martin Luther King Day 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Freethinkers Thomas Payne Day A few of the co-operating groups in Connecticut February 2018 Connecticut CoR Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 National Freedom Day Groundhog Day 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 9th – 11th Feb LogiCal LA California 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Lincoln Birthday Chinese New Darwin Day Valentine’s Day Year 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Presidents' Day 25 26 27 28 A few of the co-operating groups in Sacramento March 2018 Sacramento CoR Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 International Women’s Day 11 12 13 14 Pi Day 15 16 17 Daylight Saving Freedom of information day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 International Day of World Poetry Happiness Day 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29th Mar-1st Apr AA Convention Oklahoma City Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers (MAAF) represented at various military Bases April 2018 UnitedCoR Affiliates Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Secular Social Justice Conference Atheist Day Washington DC 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Thomas Jefferson Birthday 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 National Ask an Atheist Day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 SCA Secular Coalition for Earth Day America Lobby day 29 30 San Antonio CoR May 2018 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 International National Day of ... -

The Jewish Journal of Sociology

THE JEWISH JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY EDITOR Morris Ginsberg MANAGING EDITOR Maurice Freedman ASSISTANT EDITOR Judith Freedman VOLUME ELEVEN 1969 Published on behalf of the World Jewish Congress by William Heinemann Ltd CONTENTS 'Anti-Zionism' and the Political Kaifeng Jewish Community: A Struggle within the Elite of Summary, The by Donald Daniel Poland by Celia Stopnicka Helter zg Leslie 175 Appeal of Hasidism for American Mixed Marriage in an Israeli Town Jewry Today, The by Efraim by Erik Cohen 41 Shmueli 5 New Left and the Jews, The by Australian Jewry in 1966 by Walter JYathan Glazer 121 M. Lippmnean 67 Note on Aspects of Social Life Books Received i 13, 260 among the Jewish Kurds of Books Reviewed 31 119 Sanandaj, Iran, A by Paul 3. Book Reviews 97, 237 Magnarella 5 1 Chronicle 108, 255 Note on Identificational Assimila- Edgware Survey: Factors in Jewish tion among Fortyjews in Malmo, Identification, The by Ernest AbyLivaHerz 16 Krazjsz 151 Notes on Contributors 115, 261 Edgware Survey: Occupation and Notice to Contributors 4, 120 Social Class, The by Ernest On the Civilizing Process (Review Kra nez 75 Article) by Martin C. Albrow 227 Jewish Populations in General Reconstitution of Jewish Com- Decennial Population Censuses, munities in the Post-War Period, 1955-61: A Bibliography by The by Daniel 3. Etazar 187 Erich Rosenthal 31 University Education among Iraqi- Born Jews by Hayyimn Y. Cohen 59 AUTHORS OF ARTICLES Albrow, M.C. 227 Krause, E. 75, 151 Cohen, E. 41 Leslie, D. D. 575 Cohen, H. J. 59 Lippmann, W. M. 67 Elazar, D. -

Photo Calendar 2018

Central & Eastern Iowa CoRs January 2018 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 New Year's Day 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Martin Luther King Day 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Freethinkers Thomas Payne Day A few of the co-operating groups in Connecticut February 2018 Connecticut CoR Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 National Freedom Day Groundhog Day 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 9th – 11th Feb LogiCal LA California 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Lincoln Birthday Chinese New Darwin Day Valentine’s Day Year 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Presidents' Day 25 26 27 28 A few of the co-operating groups in Sacramento March 2018 Sacramento CoR Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 International Women’s Day 11 12 13 14 Pi Day 15 16 17 Daylight Saving Freedom of information day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 International Day of World Poetry Happiness Day 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29th Mar-1st Apr AA Convention Oklahoma City Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers (MAAF) represented at various military Bases April 2018 UnitedCoR Affiliates Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Secular Social Justice Conference Atheist Day Washington DC 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Thomas Jefferson Birthday 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 National Ask an Atheist Day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 SCA Secular Coalition for Earth Day America Lobby day 29 30 San Antonio CoR May 2018 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 International National Day of ... -

New Humanist (Rationalist Association) - Discussing Humanism, Rationalism, Atheism and Free Thought

New Humanist (Rationalist Association) - discussing humanism, rationalism, atheism and free thought Share Report Abuse Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In Ideas for godless people NEW HUMANIST MAGAZINE | BLOG Thursday, 12 May 2011 Where to buy New Humanist New campaign launches after school invites creationist preacher to revision day As part of new campaign, Creationism In Schools Isn't Science (CrISIS), launched with the backing of the British Centre for Science Education, the Christian think-tank Ekklesia and the National Secular Society, a group of leading scientists, educators and campaigners have today written to the Education Secretary, Michael Gove, urging him to clarify government guidelines preventing the teaching of creationism as science in British Twitter Schools. New Humanist The launch of CrISIS was prompted by NewHumanist Laura Horner, a parent of children at St Peter's Church of England School in Exeter. In March, Philip Bell, an evangelical preacher who @teachingofsci You are right- runs the UK arm of the young-earth creationist organisation Creation its a problem with Blogger, Ministries International, was invited by St Peters to lecture at a revision which I hope they can fix day for GCSE RE pupils. When Horner complained to the school, she 3 days ago · reply · retweet · favorite received a letter which described modern biology as "evolutionism" and Is it a noble instinct or a Bell as a “scientist” who “presented arguments based on scientific destructive desire? Delving into theory for his case". the pathology of collecting: http://bit.ly/kFZ72q Speaking about the launch of CrISIS, Horner said: 3 days ago · reply · retweet · favorite "I was appalled to find out that my children had been exposed to @robbiechicago Shame it was preserved for posterity then: this dangerous nonsense and I am determined that the Secretary http://bit.ly/iTPJyx of State for Education should urgently plug the loophole that 3 days ago · reply · retweet · favorite allows creationists to do this. -

Automated Knowledge Enrichment for Semantic Web Data

AUTOMATED KNOWLEDGE ENRICHMENT FOR SEMANTIC WEB DATA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Supervisors: Dr. Quan Bai Dr. Jian Yu Dr. Qing Liu November 2018 By Molood Barati School of Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences Copyright Copyright in text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the Author and lodged in the library, Auckland University of Technology. Details may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the Author. The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the Auckland University of Technology, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made available for use by third parties without the written permission of the University, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement. Further information on the conditions under which disclosures and exploitation may take place is available from the Librarian. © Copyright 2019. Molood Barati ii Declaration I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the qualification of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institution of higher learning. -

Atheisms Unbound: the Role of the New Media in the Formation of a Secularist Identity

Atheisms Unbound: The Role of the New Media in the Formation of a Secularist Identity Christopher Smith1 Independent Scholar Richard Cimino Hofstra University ABSTRACT: In this article we examine the Internet’s role in facilitating a more visible and active secu- lar identity. Seeking to situate this more visible and active secularist presence—which we consider a form of activism in terms of promoting the importance of secularist concerns and issues in public dis- course—we conclude by looking briefly at the relationship between secularist cyber activism and secu- lar organizations, on one hand, and the relationship between secularist activism and American politics on the other. This allows us to further underscore the importance of the Internet for contemporary sec- ularists as it helps develop a group consciousness based around broadly similar agendas and ideas and secularists’ recognition of their commonality and their expression in collective action, online as well as off. KEYWORDS: NEW MEDIA, ATHEISM, INTERNET, SECULARISM 1 Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Christopher Smith, [email protected] m . The authors would like to thank the reviewers and the editor for their advice and assistance. Secularism and Nonreligion, 1, 17-31 (2012). © Christopher Smith and Richard Cimino. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Published at: www.secularismandnonreligion.org. ATHEISMS UNBOUND SMITH AND CIMINO Introduction In recent years many websites and blogs promoting, discussing, referencing, reflecting on, and cri- tiquing atheism have appeared. Such sites have opened up an active space for atheists to construct and share mutual concerns about their situation at a time when American public life is still largely function- ing under a norm of religiosity in many contexts (Cimino & Smith, 2011). -

Canadian Atheist, Not a Member of In-Sight Publishing, 2017-2019 This Edition Published in 2019

1 2 IN-SIGHT PUBLISHING Published by In-Sight Publishing In-Sight Publishing Langley, British Columbia, Canada in-sightjournal.com First published in parts by Canadian Atheist, Not a member of In-Sight Publishing, 2017-2019 This edition published in 2019 © 2012-2019 by Scott Douglas Jacobsen. Original appearance in Canadian Atheist. All rights reserved. No parts of this collection may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized, in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented or created, which includes photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Published in Canada by In-Sight Publishing, British Columbia, Canada, 2019 Distributed by In-Sight Publishing, Langley, British Columbia, Canada In-Sight Publishing was established in 2014 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the publishing industry. In-Sight Publishing operates in independent and public interests rather than for private gains, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, ways of community, cultural, educational, moral, personal, and social value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. Thank you for the download of this e-book, your effort, interest, and time support independent publishing purposed for the encouragement of academic freedom, creativity, diverse voices, and independent thought. Cataloguing-in-Publication Data No official catalogue record for this book. Jacobsen, Scott Douglas, Author Canadian Atheist: Set VI/Scott Douglas Jacobsen pages cm Includes bibliographic references, footnotes, and reference style listing. In-Sight Publishing, Langley, British Columbia, Canada Published electronically from In-Sight Publishing in Langley, British Columbia, Canada 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed by Scott Douglas Jacobsen 3 Contents I Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. -

Addington Ku 0099D 14365 D

Drawing Lines and Taking Sides: An Examination of Boundary Work among Oppositional Worldviews By Aislinn R. Addington Submitted to the graduate degree program in Sociology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Brian Donovan ________________________________ Kelly Chong ________________________________ Lynn Davidman ________________________________ David J. Ekerdt ________________________________ Alesha Doan Date Defended: October 21, 2015 ii The Dissertation Committee for Aislinn R. Addington certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Drawing Lines and Taking Sides: An Examination of Boundary Work among Oppositional Worldviews ________________________________ Chairperson Brian Donovan Date approved: October 21, 2015 iii ABSTRACT Christians and atheists have clashed publicly over ideological tensions throughout the history of the United States. Active atheists and evangelical Christians have, and continue to, vie for legitimacy and access to power, often at the expense of those with whom they disagree. This research investigates identity, boundary work, and the relationship to the “other” between and within these two oppositional ideologies. Findings demonstrate how, in a variety of situations and settings, these two groups not only “other” each other, but use their “other” to bolster their own ideological community. The presence of a group with an oppositional worldview allows each community to further define itself, and individuals within each group to define and refine their own identity within the group. The data for this research is made up of 45 interviews and multiple sessions of participant observation. After analyzing the data, four substantive areas emerged as prominent fields for boundary work within and between both groups: Boundaries and Solidarity, Boundaries and Morality, Boundaries and Gender, and Boundaries and Technology. -

The New Hampshire Gazette, Friday, September 27, 2019 — Page 1

The New Hampshire Gazette, Friday, September 27, 2019 — Page 1 Vol. CCLXIV, No. 1 The New Hampshire Gazette Grab Me! September 27, 2019 The Nation’s Oldest Newspaper™ • Editor: Steven Fowle • Founded 1756 by Daniel Fowle PO Box 756, Portsmouth, NH 03802 • [email protected] • www.nhgazette.com I’m Free! The Fortnightly Rant Counting On a Stable Genius y now, most Americans are at Anyone bothering to watch this least somewhat inured to seeing mundane event could easily have Bthe business of state conducted with thought, “this is how our govern- all the dignity of a child’s sidewalk ment is supposed to function.” At lemonade stand. Given the trap- best they’d be half-right. Nearly a pings available to the world’s most thousand days into the Trump Era, powerful office, of course, the spe- a yearning for tedium is a sign of cific elements are a little bit grander good mental health. Just beneath the than the usual card table and hand- seamless decorum of the September scrawled signage. For example, the 20th press conference, though, is a Potentate of the Potomac routinely conglomerated mess of tangled in- addresses broadcast journalists from terests as convoluted and malign as the lawn of the White House, with one of His Excellency’s off-the-cuff Marine One idling in the back- word salads. ground. The big Sikorsky serves sev- Soon hundreds of those troops, eral purposes. The sight of it conveys whom we all profess to love so dear- an image of might and authority, ly, will be packing their duffel bags impressing authoritarian rubes; it for Saudi Arabia. -

Blasphemy Free Download

BLASPHEMY FREE DOWNLOAD Douglas J Preston | 526 pages | 30 Dec 2008 | St Martin's Press | 9780765349668 | English | New York, United States Examples of Blasphemy Then he told us Blasphemy this wandering mass of blasphemy got his name of "Spreetoo Santoo. In England, under common lawblasphemy came Blasphemy be punishable by fine, imprisonment or corporal punishment. Retrieved 20 Blasphemy A crime under the common law if the blasphemy was directed towards Christianity Blasphemy Christian doctrine and Blasphemy and is still a statutory crime although rarely Blasphemy in many states. Then This Is a Must-Read. However, these were very activities Blasphemy the Blasphemy attributed to the work of Satan. Blasphemy Blasphemy and the United Nations. Retrieved 10 November We're gonna stop you right there Literally Blasphemy to use a word Blasphemy literally drives some pe In the Guru Granth Sahib, page 89—2, [66]. More Definitions for blasphemy. Dictionary Entries near blasphemy blaspheme blaspheme-vine blasphemous blasphemy blast blast- -blast See More Nearby Entries. Who Jesus is His identity dictates what Jesus does His mission. Blackstonein his Blasphemydescribed the offence as. More Blasphemy Examples Additional examples of blasphemy from the news include the following: Ina Hindu principal in Pakistan was Blasphemy for committing blasphemy against the prophet during his lesson, inciting a riot. Explore different examples of blasphemy. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blasphemy. Take the quiz Spell It Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? Nor would it be permissible Blasphemy such prohibitions to be used to prevent or punish criticism of religious leaders or commentary on Blasphemy doctrine and tenets of faith.