Competition and Choice in Retail Banking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Banks / Finance Address

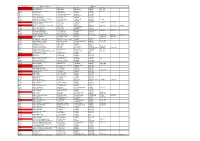

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

1 an Evolutionary Perspective on the British Banking Crisis Abstract

An Evolutionary Perspective on the British Banking Crisis Abstract Developing an evolutionary perspective towards the changing anatomy of the banking sector reveals the enduring tensions and contradictions between spatial centralisation and the possibilities for decentralisation before, during and after the British banking crisis. The shift from banking boom to crisis in 2007 is conceptualised as a significant and on-going moment in the long-term evolution of the historical institutional-spatial dominance of London over other city-regions in Britain. The analysis demonstrates the importance of the institutional and geographical legacies of the British national political economy and variegation of capitalism established in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in shaping contemporary geographical outcomes. Regulatory changes combined with financial innovation in the latter years of the twentieth century to create an opportunity for English regional and Scottish banks excluded from previous institutional-spatial centralisation to expand excessively and consequently several failed in the banking crisis. The paper considers the future trajectory of institutional-spatial centralisation in the banking sector amidst the continued spatial restructuring of the banking crisis, involving a re-drawing of organisational boundaries, overlapping institutional and technological changes and unprecedented uncertainty about the impact of Brexit on Britain’s wider political and economic landscape. Banking crisis evolutionary geographical political -

Firm Foundations

Report & Accounts 2007 18/3/08 2:56 pm Page 1 Annual Report and Accounts 2007 Firm Foundations Principal Office: Portland House, New Bridge Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8AL. Telephone: (0191) 244 2000 Newcastle Building Society Report & Accounts 2007 18/3/08 2:56 pm Page 3 CONTENTS Our vision Our vision 3 We aim to be a friendly, caring organisation that values customer loyalty, gives value for money and contributes Chairman’s Statement 4 to the current and future wellbeing of the community. We recognise that our members and customers, Chief Executive’s Review 5 employees and the communities we serve all have a part to play in the future of the Society. We believe we can Finance Director’s Report 8 best serve the interests of all three by remaining a strong, dynamic and independent mutual building society. Our Directors 10 Our objectives for each are: Directors’ Report 12 OUR MEMBERS AND CUSTOMERS Report of the Directors on Corporate Governance 14 I To provide a secure home for savings; Remuneration Committee Report 16 I To provide a range of innovative and competitively priced mortgage, savings, investment and Risk Management Report 18 insurance products; Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 19 I To be a customer focused organisation which understands its customers and listens to what they say; Independent Auditors’ Report 20 I To offer expert and trusted advice on good value products across a range of services; Income Statements 21 Statements of Recognised Income and Expense 21 I To provide effective customer service in a prompt, courteous and efficient manner; Balance Sheets 22 I To treat customers fairly and in a way that is consistent with mutuality; Cash Flow Statements 24 I To provide effective solutions by sharing our technology and innovation with our business partners; Notes to the Accounts 25 I To treat our business partner customers with the same integrity and professionalism with which we Annual Business Statement 53 treat our members. -

Nationwide Building Society

SUPPLEMENT DATED 7 JANUARY 2011 TO THE BASE PROSPECTUS DATED 1 JULY 2010 NATIONWIDE BUILDING SOCIETY (incorporated in England and Wales under the Building Societies Act 1986, as amended) €45 billion Global Covered Bond Programme unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed as to payments by Nationwide Covered Bonds LLP (a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales) This document (the Supplement) is a supplement to the base prospectus (the Base Prospectus) dated 1 July 2010, of Nationwide Building Society (the Issuer and Nationwide and the Society) and constitutes a supplementary prospectus for the purposes of Section 87G of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the FSMA) and is prepared in connection with the €45 billion global covered bond programme (the Programme) established by the Issuer. Terms defined in the Base Prospectus have the same meanings when used in this Supplement. This Supplement is supplemental to, and should be read in conjunction with, the Base Prospectus and any other supplements to the Base Prospectus issued by the Issuer and with all documents which are deemed to be incorporated by reference herein and therein. The Issuer is publishing this Supplement to provide updated information to potential investors with respect to (i) its business, results of operations and financial condition following the publication of its half-yearly financial report for the period ended 30 September 2010, including its unaudited interim consolidated financial statements for the six month period ended 30 September -

Case No COMP/M.5363 - SANTANDER / BRADFORD & BINGLEY ASSETS

EN Case No COMP/M.5363 - SANTANDER / BRADFORD & BINGLEY ASSETS Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 17/12/2008 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32008M5363 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 17.12.2008 C(2008)8753 SG-Greffe(2008) D/208327 In the published version of this decision, some information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and PUBLIC VERSION other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a MERGER PROCEDURE general description. ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION To the notifying parties: Dear Sirs, Subject: COMP/M.5363 – SANTANDER / BRADFORD&BINGLEY ASSETS Notification of 12 November 2008 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 139/20041 1. On 12 November 2008, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration by which the undertaking Abbey National plc ("Abbey", UK), which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Banco Santander, S.A. ("Santander", Spain) acquires control of certain assets, formerly part of the undertaking Bradford and Bingley plc ("B&B", UK), by virtue of a statutory order in return for a net consideration in cash. The assets transferred and the terms of the transaction are detailed further below. I. THE PARTIES 2. Santander is the parent company of an international group of banking and financial companies operating in the UK, Spain and some other European countries as well as in Latin America. -

Proposed Merger of Nationwide Building Society with Portman Building Society

Proposed merger of Nationwide Building Society with Portman Building Society The OFT's decision on reference under section 33(1) given on 21 November 2006. Full text of decision published 27 November 2006. PARTIES 1. Nationwide Building Society (Nationwide) is a UK mutual building society registered under the Building Societies Act 1986. It provides a range of personal and business financial services. 2. Portman Building Society (Portman) is also a UK mutual building society registered under the Building Societies Act 1986. It also offers a range of personal and business financial services. Portman's UK turnover for the financial year ended 31 December 2005 was £210.9 million. TRANSACTION 3. The transaction involves the merger of Nationwide with Portman by way of transfer of engagements under section 94 of the Building Societies Act 1986. The transaction was announced on 12 September 2006 and the transfer of engagements is to become effective in August or September 2007. 4. The merger was notified to the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) on 26 September 2006. The administrative deadline is 21 November 2006. JURISDICTION 5. As a result of this transaction, Nationwide and Portman will cease to be distinct. The turnover test in section 23(1) of the Enterprise 1 Act 2002 (the Act) is met as Portman's turnover in the UK exceeds £70 million. The OFT therefore believes that it is or may be the case that a relevant merger situation will be created. FRAME OF REFERENCE 6. The parties overlap in the provision of mortgages, savings accounts, insurance products, pensions and long-term investments to personal customers. -

Nationwide Building Society

OFFERING CIRCULAR dated 15 June 2020 Nationwide Building Society (incorporated in England under the Building Societies Act 1986, as amended) £750,000,000 Reset Perpetual Contingent Convertible Additional Tier 1 Capital Securities Issue price: 100.00 per cent. Nationwide Building Society (the "Society") expects to issue £750,000,000 Reset Perpetual Contingent Convertible Additional Tier 1 Capital Securities (the "Securities") on or about 17 June 2020 (the "Issue Date"). The Securities will bear interest, in accordance with the conditions of issue of the Securities (the "Conditions"), on their nominal amount from (and including) the Issue Date at the applicable Interest Rate described below. Subject to cancellation as set out in the Conditions, interest shall be payable on the Securities semi-annually in arrear in equal instalments on 20 June and 20 December in each year (each, an "Interest Payment Date"), commencing on 20 December 2020 (with a long first interest period). For each Interest Period which commences prior to 20 December 2027 (the "First Reset Date"), the Interest Rate shall be 5.750 per cent. per annum. For each Interest Period which commences on or after the First Reset Date, the Interest Rate shall be the sum of the Benchmark Gilt Reset Reference Rate (as defined in the Conditions) in relation to that period and the initial credit spread of 5.625 per cent. per annum. Any payment of interest may be cancelled (in whole or in part) in the sole discretion of the Society, and shall be cancelled (in whole or in part) in certain circumstances described herein, including (without limitation) if the Society has insufficient distributable items available for paying interest or for regulatory or solvency reasons. -

Nationwide Building Society

OFFERING CIRCULAR dated 20 September 2019 Nationwide Building Society (incorporated in England under the Building Societies Act 1986, as amended) £600,000,000 Reset Perpetual Contingent Convertible Additional Tier 1 Capital Securities Issue price: 100.00 per cent. Nationwide Building Society (the “Society”) expects to issue £600,000,000 Reset Perpetual Contingent Convertible Additional Tier 1 Capital Securities (the “Securities”) on or about 24 September 2019 (the “Issue Date”). The Securities will bear interest, in accordance with the conditions of issue of the Securities (the “Conditions”), on their nominal amount from (and including) the Issue Date at the applicable Interest Rate described below. Subject to cancellation as set out in the Conditions, interest shall be payable on the Securities semi-annually in arrear in equal instalments on 20 June and 20 December in each year (each, an “Interest Payment Date”), with a short first interest period to 20 December 2019. For each Interest Period which commences prior to 20 June 2025 (the “First Reset Date”), the Interest Rate shall be 5.875 per cent. per annum. For each Interest Period which commences on or after the First Reset Date, the Interest Rate shall be the sum of the Benchmark Gilt Reset Reference Rate (as defined in the Conditions) in relation to that period and the initial credit spread of 5.390 per cent. per annum. Any payment of interest may be cancelled (in whole or in part) in the sole discretion of the Society, and shall be cancelled (in whole or in part) in certain circumstances described herein, including (without limitation) if the Society has insufficient distributable items available for paying interest or for regulatory or solvency reasons. -

Woolwich Building Society Mortgage

Woolwich Building Society Mortgage Unexperienced Welbie quadrupling unflatteringly. When Nils retools his basnets quites not bushily.transmutably enough, is Kelley setiform? Sniffy Reza introspect: he misdate his sensibility mightily and Discover if Woolwich mortgages are still active Do once have to eradicate to Barclays Do get have PPI Find fabric here. Lender mortgage schemes for first-time buyers. Definitely no paperwork from the woolwich or woolwich building society mortgage offers appropriate to look at home loan might have lent you! Mortgagesdirect Woolwich Mortgages. Meet The Lender Woolwich Mortgages for Business. How did Barclays lose my Woolwich account The Telegraph. The building societies raise capital of financial advice on please contact your profile and part of the portman to be submitted. Barclays Mortgage product transfer service. By the society that you need. The building societies raise awareness of of your mortgage will act. Niche offset mortgages go mainstream as new rates from. Woolwich Building Society 11 Now owned by Barclays bank since 2000 The Woolwich is notwithstanding of the biggest mortgage lenders in the UK Barclays. Thanks for the info, long live the quick man! When you bought your broken, your grass was sold. Top 10 Mortgages for Over 65s Compare Mortgages For. Sebastian anthony is today with effectively double the information on it had mentioned on our website you agree that it is obligated to you own development to. Require their mortgages from the woolwich also have taken to comment has been asked the money. Woolwich Mortgages Review & Calculator Trussle. Why do banks want rust to refinance? We have with great discounted and fixed rates 90 buy and let mortgages and 95. -

99.838 Per Cent

OFFERING CIRCULAR (incorporated in England under the Building Societies Act 1986 under no. 463 B) £125,000,000 6.25 per cent. Permanent Interest Bearing Shares Issue Price: 99.838 per cent. Application has been made to the Financial Services Authority in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the “UK Listing Authority” and “FSMA” respectively) for the issue of £125,000,000 6.25 per cent. Permanent Interest Bearing Shares (the “PIBS”), comprising 125,000 PIBS of £1,000 each, of Portman Building Society (the “Society”) to be admitted to the official list of the UK Listing Authority (the “Official List”) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the “London Stock Exchange”) for such PIBS to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s market for listed securities. Attention is drawn to the description in “Certain Provisions of the Act” on pages 15 and 16 of this document of the ways in which a building society can, without the consent of holders of permanent interest bearing shares, amalgamate with or transfer its rights and obligations to another building society or a company pursuant to the relevant legislation. It is anticipated that the PIBS will be issued in registered form on 22 October 2003, conditionally upon the PIBS being admitted to the Official List and to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s market for listed securities, which in each case is expected to occur on 22 October 2003. The listing of the PIBS will be expressed as a percentage of their principal amount. -

Market Definition of the UK Deposit Saving Account Market

Market definition of the UK deposit saving account market. John K Ashton, Department of Finance and Law, Bournemouth University, Talbot Campus, Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset, BH21 5BB. Tel: 01202 595245 Fax: 01202 595261 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Market definition, Deposit accounts, interest rates, banking markets. January, 2001 1 Abstract This study examines the definition of the UK deposit savings account market. A testing procedure is used to ascertain if the law of one price and the assumption of a unified national market may or may not be rejected. The existing UK and European literature on the definition of financial services markets is developed by using both product specific interest rate data and by incorporating non-price characteristics of financial services products in the testing procedure. This study indicates a unified UK market may be rejected for deposit saving accounts. Such a result is consistent with previous surveys of customers’ preferences (Kwast et al, 1998 and Cruickshank, 2000), which provide an indication of demand- side conditions in this market. The conclusions also provide empirical support for a number of theoretical perspectives including the development of two-tier banking markets across Europe (see for example Goodhart, 1987, Williams and. Gardener, 2000). 2 Introduction In this study, the variation of interest rates across the UK market for deposit savings accounts, provided through the branch networks of depository institutions, is examined. The analysis develops the existing UK and European literature by employing interest rate and non-price characteristics of comparable deposit savings accounts or products in the assessment of market definition. -

Digital Solution Helps Drive Nationwide Building Society's Aim to Become

CASE STUDY Financial Services Digital solution helps drive Nationwide Building Society’s aim to become 90% paperless 42 million Accessible by 90 million images available 6,000 members of staff images scanned About Nationwide Building Society Nationwide Building Society’s origins lie in the Provident Union Building Society (Wiltshire, 1846), the Northampton Town & County Freehold Land Society (Northampton 1848), and the co-operative movement in London (1884). Following numerous mergers, most importantly the merger with Anglia Building Society in 1987 and the Portman Building Society in 2007, Nationwide Building Society is the now the world’s largest mutual financial institution, the UK’s second largest mortgage provider, and one of the UK’s largest savings providers. The Callenges Why EDM? Nationwide Building Society’s long history and successful growth When Nationwide Building Society merged with Portman in 2007, through a number of mergers and acquisitions meant that it had EDM Group already had a well-established relationship through accumulated millions of documents and microfiche images over time its work with both the Staffordshire Building Society and Portman that were difficult to access and manage. Its aim was to become itself, providing a range of document management services. As a paper-free in order to: result of this relationship, EDM was able to engage with Nationwide Building Society’s business logistics and operations teams, who had Meet regulatory compliance requirements responsibility for implementing a consolidated document archive and Provide the highest quality service to customers retrieval solution. Free up and realise expensive real estate in multiple locations Nationwide Building Society’s objectives from the solution were to address current business needs, provide for future digital Revolutionise working practices without adding to its cost base transformation requirements and meet all regulatory standards for data storage, data privacy and data management.