Violet N Okemaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

An Examination of Aboriginal Post-Secondary

THE POLITICS OF INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT : AN EXAMINATION OF ABORIGINAL POST-SECONDARY INSTITUTIONS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA AND SASKATCHEWAN A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Master of Arts In the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Helen Weir © Copyright Helen Weir, April 2003 . All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission . It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis . Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to : Head of the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT The central objective of this study is to examine the politics and policies regarding the development and operation of Aboriginal controlled post-secondary institutions, especially First Nations initiated post-secondary institutions in Western Canada. -

Indigenous Women and Feminism

INDIGENOUS WOMEN AND FEMINISM © UBC Press Sample Chapter suzack hi_res.pdf 1 9/14/2010 12:00:23 PM Women and Indigenous Studies Series The series publishes works establishing a new understanding of Indigenous women’s perspectives and experiences, by researchers in a range of fields. By bringing© women’s UBC issues to the forefront, Press this series invites and encourages innovative scholarship that offers new insights on Indigenous questions past, present, and future. Books in this series will appeal to readers seeking stimu- lating explorations and in-depth analysis of the roles, relationships, and representations of Indigenous women in history, politics, culture, ways of knowing,Sample health, and community well-being. Chapter Other books in the series: Being Again of One Mind: Oneida Women and the Struggle for Decolonization, by Lina Sunseri Taking Medicine: Women’s Healing Work and Colonial Contact in Southern Alberta, -, by Kristin Burnett repl ii.pdf 1 9/14/2010 2:55:34 PM INDIGENOUS WOMEN AND FEMINISM Politics, Activism, Culture Edited by Cheryl Suzack, Shari M. Huhndorf, Jeanne Perreault, and Jean Barman © UBC Press Sample Chapter suzack hi_res.pdf 3 9/14/2010 12:01:01 PM © UBC Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. Printed in Canada on FSC-certified ancient-forest-free paper (% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free. -

Best Practices in Increasing Aboriginal PS Enrolment Rates…

Best Practices in Increasing Aboriginal Postsecondary Enrolment Rates Prepared for The Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) Prepared by R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. 3rd Floor 910 View Street Victoria, BC V8V 3L5 Phone: (250) 384-2770 Fax: (250) 384-2774 May 2002 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... 4 Section A INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY........................................................... 5 Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 7 Methodological Challenges ................................................................................................. 9 Section B THE STATE OF ABORIGINAL POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION................ 11 Aboriginal Education Attainment Data.............................................................................. 11 Barriers to Aboriginal Postsecondary Success in Canada ............................................... 14 Existing Initiatives or Programs......................................................................................... 21 Section C BEST PRACTICES: LESSONS AND SHORTCOMINGS ............................... -

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada This report is in the public domain. Anyone may, without charge or request for permission, reproduce all or part of this report. 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Website: www.trc.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future : summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Issued also in French under title: Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir, sommaire du rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Issued also in printed form. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-660-02078-5 Cat. no.: IR4-7/2015E-PDF 1. Native peoples--Canada--Residential schools. 2. Native peoples—Canada--History. 3. Native peoples--Canada--Social conditions. 4. Native peoples—Canada--Government relations. 5. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 6. Truth commissions--Canada. I. Title. II. Title: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. E96.5 T78 2015 971.004’97 C2015-980024-2 Contents Preface ........................................................................................................ -

Loss and Revitalization of First Nations Languages in Manitoba

1 LOSS AND REVITALIZATION OF FIRST NATIONS LANGUAGES IN MANITOBA An Investigation into the Loss and Revitalization of First Nations Languages in Manitoba: Perspectives of First Nations Educators By: Adeline Mercredi A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of MASTER IN EDUCATION Faculty of Education University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2021 Adeline Mercredi 2 LOSS AND REVITALIZATION OF FIRST NATIONS LANGUAGES IN MANITOBA Abstract The main purpose of this research is to utilize the perspectives of research participants to address language loss in First Nations schools in Manitoba. The current status of some Aboriginal [Indigenous] languages are considered to be endangered (Statistics Canada, 2016). Most may be lost if we do not address this critical state. Indigenous languages are vital to the culture and knowledge systems of Indigenous peoples. The Indigenous Languages Act (2019) is now legislation after having passed its third reading through parliament. This Act gives hope for much needed funding to implement strategies for retaining and revitalizing Indigenous languages. It is hoped that the Indigenous Languages Act will help to empower Indigenous people to promote the worldview that highlights the importance of the Indigenous cultures and languages. It is important to note that the colonization process has had the most detrimental effect on language loss (Kirkness, 1998). As Kirkness had indicated in her 1998 collection of talks and papers: The intergenerational impacts of the residential school era have seriously disrupted the transmission of Indigenous languages. The power of government systems imposed over Indigenous peoples has also severely affected the retention of Indigenous languages. -

Stories of Secwepemc Immersion from Chief Atahm School

Trickster’s Path to Language Transformation: Stories of Secwepemc Immersion from Chief Atahm School by Kathryn A. Michel B.A., University of British Columbia, 1987 M.A. Ed., Simon Fraser University, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Educational Leadership and Policy) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2012 © Kathryn A. Michel, 2012 Abstract I am a Secwepemc woman. I weave my identity around my land, my nation, and my family. My journey has led me to live my life working to help revitalize the Secwepemc language through immersion education. Through this qualitative study, framed by the oral tradition of stsptekwle, I share stories of my own involvement in language regeneration and stories from community members who worked alongside me to develop an Indigenous immersion school. These stories are set within the village of Sexqeltqin, in the South-Central Interior of British Columbia. They focus on the early experiences of the founding members of Chief Atahm School to help uncover how an Indigenous community, filled with hegemonic beliefs of its own obsolescence, worked to reconnect the self to community, through language. Throughout this research journey, narrative and autoethnographical elements merge with the Secwepemc oral tradition. Through using the oral tradition as a theoretical and conceptual tool, I reframe Aboriginal language revitalization as a journey of reconnecting self to community. The development of the “Restorying” Coyote Research and Theoretical Model not only asserts my rights as a Secwepemc researcher, but also, my responsibility to give back to community. -

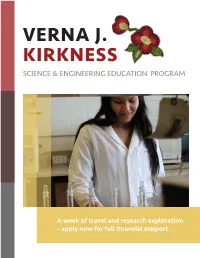

Verna J. Kirkness Science and Engineering Education Program

VERNA J. KIRKNESS SCIENCE & ENGINEERING EDUCATION PROGRAM A week of travel and research exploration - apply now for full fnancial support. CONNECTING STUDENTS FROM ACROSS CANADA The Verna J. Kirkness Science and Engineering Education program ofers scholarships to First Nations, Métis and Inuit grade 11 students to spend a week as a student researcher at a Canadian university, interacting with scientists in their research laboratories. During their week on campus the students have the opportunity to meet role models, learn about the support systems that are available to them on campus and experience the excitement of doing research. There are several participating universities across Canada, bringing together youth from all corners of the country to experience the unique learning experience the Verna J. Kirkness Science and Engineering Education program has to ofer. “This program not only educated me on how I could be involved in the science and engineering world, but “If more people in my exposed me to the world of university. Coming from a community were aware of small town this was single handedly the most impactful how much science comes into moment in my life. It gave me the confdence and our everyday lives, I feel like reassurance that there is a place for me in the world to there would be way more jobs do whatever I want wherever I want.” and interest... This program is - Drew - Courtenay, BC opening my eye to university life. Also it’s encouraging me to pursue fnishing high school, and get ready for my future” “ The Verna.J.Kirkness program has helped me in so - Sara - Gift Lake, AB many ways, it has given me valuable learning tools in my quest for post-secondary. -

Indigenous Peoples, Global Issues and Sustainability

Indigenous Peoples, Global Issues, and Sustainability IndigenousIndigenous Peoples, Peoples, Global Global Issues, Issues, and and Sustainability Sustainability Introduction From time immemorial, the First Peoples (ancestors of today’s First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) inhabited every region of the land that would become Canada. From the coastal areas west of the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean to the Arctic and sub-Arctic to the Great Plains, there was a great diversity in language and culture. Within each cultural grouping, there were many distinct languages and dialects. Equally diverse were the social customs, economies, political practices, and spiritual beliefs of the First Peoples. Communities ranged in size from single-family hunting groups typical of the Arctic to the multi- nation confederacy that was the achievement of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois). Whatever their size or political sophistication, First Peoples’ social organizations were based on the family. All Canadians can benefit from the preservation of unique Indigenous identities in that there are many things to learn from the variety of traditions and beliefs of Indigenous Peoples. For example, environmental stewardship, cooperation, and community development are all aspects of Indigenous worldviews that would be beneficial to Canada as a whole. As Canada is a multicultural country, everyone can learn from the cultures of others. BG-13.3 IndigenousIndigenous Peoples, Peoples, Global Global Issues, Issues, and and Sustainability Sustainability Exploring the Issues Define Indigenous. The United Nations has spent a lot of time discussing the definition of “Indigenous Peoples,” but Indigenous organizations have rejected the idea of adopting such a formal, universal definition. They believe Indigenous Peoples ought to define themselves for themselves rather than have a definition imposed on them. -

Gi-Miigiwemin Gi-Gikinô' Amaagoowininaan

Gi-miigiwemin Gi-gikinô’ amaagoowininaan: Giving of Our Scholarly Learning 2011 Profile of Students in the PhD Studies for Aboriginal Scholars (PSAS) Program Dedicated to our families and the mentors and Elders who have helped each of us on the paths of our life journeys. Miigwetch! Chi-miigwetch! Ekosi! Pidamaya! Marci/Marsi/ Marsee! Merci! Thank you! © PSAS Program, 2011, University of Manitoba The title of this publication was gifted by: Helen Agger and her mother, Dedibaayaanimanook Sarah Keesick Olsen The majority of the photos in this publication, plus the design and layout were provided courtesy of: EB2 (Imaging, Design & Research) Proprietors: Marlyn Bennett and Mike Elliott Email: [email protected] Printed by: All Nations Print Ltd. http://www.allnationsprint.com This publication is available online at: http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/graduate_studies/admissions/programs/doctoral/554.htm Gi-miigiwemin Gi-gikinô’amaagoowininaan: Giving of Our Scholarly Learning 2011 Profile of Students in the PhD Studies for Aboriginal Scholars (PSAS) Program Table of Contents Members of the PSAS Council 4 Message from the Dean of Graduate Studies 5 Introduction 7 Helen Agger 9 Marlyn Bennett 11 Paul Cormier 13 Ben Dionne 15 Ryan Duplessie 17 Lorena Fontaine 19 Shirley Fontaine 21 Emily Grafton 23 April Krahn 25 Margaret Kress-White 27 Heather McRae 29 Nora Murdock 31 Sherry Peden 33 Maggie Penfold 35 Margaret Scott 37 Kandy Sinclair 39 Members of the PSAS Council1 Dr. Jay Doering, Chair Dean, Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Manitoba Dr. Deo H. Poonwassie, Coordinator Professor Emeritus, University of Manitoba Dr. Verna Kirkness, OC2, OM3; Community Representative Associate Professor Emeritus, University of British Columbia Dr. -

Spring 2014 HISTORY • ABORIGINAL STUDIES the Edge of the Woods Iroquoia, 1534 – 1701 Jon Parmenter

University of Manitoba Press 301 St. John’s College, 92 Dysart Road UMP Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3T 2M5 1083120 Distributed in Canada by UTP Distribution Distributed in the United States by Michigan State University Press University ofManitoba Press University Spring UMP 2014 Subject Index Announcing our new series: First Voices, First Texts How to Order Contact Us Aboriginal & Indigenous Studies / 1, 3, Series Editor: Warren Cariou, University of Manitoba 5, 6, 7, 10, 12, 13 Contemporary Studies on the North / 8 First Voices, First Texts aims to re-connect contemporary readers with some Individuals Editorial Office Critical Studies in Native History / 9 of the most important Aboriginal literature of the past, much of which U of M Press books are available at bookstores and University of Manitoba Press Education / 6 has been unavailable for decades. This series reveals the richness of these on-line retailers across the country. Order through 301 St. John’s College, 92 Dysart Rd., Winnipeg, MB R3T 2M5 Environment / 2, 10 works by providing newly re-edited texts that are presented with particular your local bookseller and save shipping charges, Ph: 204-474-9495 Fax: 204-474-7566 First Voices, First Tests / 1 sensitivity toward Indigenous ethics, traditions, and contemporary or order direct from uofmpress.ca or one of our www.uofmpress.ca Gender Studies / 5 realities. The editors strive to indigenize the editing process by involving distributors listed below. History / 2, 3, 4, 7, 11–13 Director: David Carr, [email protected] communities, by respecting traditional protocols, and by providing critical Examination Copy Policy Senior Acquisitions Editor: Jean Wilson, [email protected] Immigration and Culture / 4, 6, 14 introductions that give readers new insights into the cultural contexts of Please submit requests for examination copies to Managing Editor: Glenn Bergen, [email protected] Literary Criticism / 6, 8 these unjustly neglected classics. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document. Vocabularies and Dictionary Development: a Cautionary Note" (Blair A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 231 RC 023 385 AUTHOR Burnaby, Barbara Jane, Ed.; Reyhner, Jon Allan, Ed. TITLE Indigenous Languages across the Community. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Stabilizing Indigenous Languages (7th, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 11-14, 2000). INSTITUTION Northern Arizona Univ., Flagstaff. Center for Excellence in Education. ISBN ISBN-0-9670554-2-3 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 274p.; For selected individual papers, see RC 023 386-401. AVAILABLE FROM Center for Excellence in Education, Northern Arizona University, Box 5774, Flagstaff, AZ 86011-5774 ($15 plus $3.00 shipping) .Tel: 928-523-5342. For full text: http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/-jar/ILAC/. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Education; *American Indian Languages; Bilingual Education; *Community Action; Community Programs; Cultural Maintenance; Elementary Secondary Education; Eskimo Aleut Languages; Higher Education; Immersion Programs; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Maintenance; Language Planning; *Native Language Instruction IDENTIFIERS Endangered Languages ABSTRACT Conference papers examine efforts by Indigenous communities, particularly Native American communities, to maintain and revitalize their languages. The 27 papers are: "Ko te reo te mauri o te mana Maori: The Language Is the Life Essence of Maori Existence" (Te Tuhi Robust); "The Preservation and Use of Our Languages: Respecting the Natural Order of the Creator" (Verna J. Kirkness); "Maori: New Zealand Latin?" (Timoti S. Karetu); "Using Indigenous Languages for Teaching and Learning in Zimbabwe" (Juliet Thondhlana); "Language Planning in a Trans-National Speech Community" (Geneva Langworthy); "The Way of the Drum: When Earth Becomes Heart" (Grafton Antone, Lois Provost Turchetti); "The Need for an Ecological Cultural Community" (Robert N.