Mapping the Spread of Mounted Warfare Peter Turchin1,2, Thomas E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

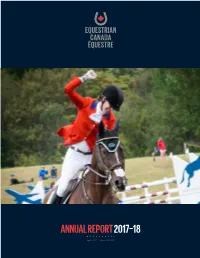

Annual Report 2017–18

ANNUAL REPORT 2017–18 April 1, 2017 — March 31, 2018 ABOUT EQUESTRIAN CANADA Equestrian Canada (EC) is the national governing body for equestrian sport and industry in Canada, with a mandate to represent, promote and advance all equine and equestrian interests. With over 16,000 Sport Licence Holders, 90,000 registered participants, 11 provincial/territorial sport organization partners and 10+ national equine affiliate organizations, EC is a significant contributor to the social, physical, emotional and economic wellbeing of the equestrian industry across Canada. OUR OUR VISION MISSION An aligned Canadian equestrian To lead, support, promote, govern and community that inspires and serves advocate for the equine and equestrian equestrians in their pursuit of personal community in Canada. excellence from pony to podium. OUR CORE VALUES WE BELIEVE IN: 04 05 Service Integrity Effectively and proactively Championing an serving the Canadian ethical, responsible and equestrian community to respectful approach to all support the advancement roles, levels and areas of of sport and industry. equestrian participation. 1 01 03 Excellence Partnership Upholding world- Generating a culture of class standards in all unity and collaboration our initiatives. across the equestrian community. 02 Welfare Protecting the safety and welfare of equestrians and equines equally. 2 Equestrian Canada Annual Report 2017-18 | 3 PROVINCIAL/TERRITORIAL PARTNERS Horse Council British Columbia Alberta Equestrian Federation Saskatchewan Horse Federation Manitoba Horse Council -

CHANGE YOUR CALENDAR – TROT's ANNUAL DINNER And

-- Join TROT today! And encourage your riding buddies to join, too! January, 2017 Founded 1980 Number 219 INSIDE THIS ISSUE CHANGE YOUR CALENDAR – TROT's ANNUAL DINNER Annual Dinner – Venue Change 1 and SILENT AUCTION is still SATURDAY, MARCH 4, President's Message 1,3 2017, 6 PM, but at HOWARD COUNTY FAIRGROUNDS Horse World Expo, Jan 20-22 2 Help Trails-Speak to Your Legislators 3 (4-H building) from Gale Monahan and Priscilla Huffman 2017 Hunting Bills 3 TROT was to hold its Annual Meeting at the Fire Hall in Mt. Airy, as it has for several Howard County Bow Hunting Bills 4 years. However, TROT just learned that their renovations are delayed, so we had to Bun Bags in Anne Arundel County? 4 !nd another option. Happily, at the Howard County Fairgrounds (where TROT held its Possible Patapsco Greenway 4 annual dinners several years ago) Gale was able to arrange for the use of their 4-H building (the !rst building on the right by the #agpole as you enter the gate) on the New trails on Pepco Powerlines 5 originally planned date. This venue is conveniently near the intersection of Rt I-70 and Rt The Lisbon Horse Parade 5 32 (2210 Fairgrounds Rd., West Friendship, MD 21794). Check the Hunt Schedule 5 TROT Awarded Grant for Display 6 All are welcome to TROT's Annual Dinner (as always, a potluck) and Silent Auction, on Saturday, March 4, 2017, at 6:00 PM. But remember, this year it will be at Rachel Carson Park 6 the 4-H building of the Howard County Fairgrounds! [NOT in Mt. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

ROMAN REPUBLICAN CAVALRY TACTICS in the 3Rd-2Nd

ACTA MARISIENSIS. SERIA HISTORIA Vol. 2 (2020) ISSN (Print) 2668-9545 ISSN (Online) 2668-9715 DOI: 10.2478/amsh-2020-0008 “BELLATOR EQUUS”. ROMAN REPUBLICAN CAVALRY TACTICS IN THE 3rd-2nd CENTURIES BC Fábián István Abstact One of the most interesting periods in the history of the Roman cavalry were the Punic wars. Many historians believe that during these conflicts the ill fame of the Roman cavalry was founded but, as it can be observed it was not the determination that lacked. The main issue is the presence of the political factor who decided in the main battles of this conflict. The present paper has as aim to outline a few aspects of how the Roman mid-republican cavalry met these odds and how they tried to incline the balance in their favor. Keywords: Republic; cavalry; Hannibal; battle; tactics The main role of a well performing cavalry is to disrupt an infantry formation and harm the enemy’s cavalry units. From this perspective the Roman cavalry, especially the middle Republican one, performed well by employing tactics “if not uniquely Roman, were quite distinct from the normal tactics of many other ancient Mediterranean cavalry forces. The Roman predilection to shock actions against infantry may have been shared by some contemporary cavalry forces, but their preference for stationary hand-to-hand or dismounted combat against enemy cavalry was almost unique to them”.1 The main problem is that there are no major sources concerning this period except for Polibyus and Titus Livius. The first may come as more reliable for two reasons: he used first-hand information from the witnesses of the conflicts between 220-167 and ”furthermore Polybius’ account is particularly valuable because he had serves as hypparch in Achaea and clearly had interest and aptitude in analyzing military affairs”2. -

Introduction 1 Introduction in a Recent Review of Guy Halsall's Warfare And

introduction 1 INTRODUCTION In a recent review of Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West, 450-900, which is ostensibly meant to be a new standard in the field, Bryan Ward-Perkins approves of the author’s findings, summarizing of early medieval warfare that: It remains very difficult to imagine a seventh- or eighth-century army, except as a hairy and ill-equipped horde, or as a Beowulfian band of heroes, and almost impossible to envisage what such an army did when faced with an obstacle such as a walled town[.]1 Ward-Perkins is being willfully—not to say wonderfully—provocative. He is well aware of the substantial and growing body of scholarship on early medieval warfare that has rendered clichés of hairy barbarians obsolete.2 But quips aside, he highlights a serious gap in existing historiography. While many scholars recognize the similarity (and to varying extents con- tinuity) between Roman and high medieval siege warfare, this has never been demonstrated in any detail. Hence, a notable number of scholars favor a minimalist interpretation of warfare in which the siege is accorded little importance, especially in the West, arguing that post-Roman society lacked the necessary demographic, economic, organizational and even cultural prerequisites. Continuity of military institutions is unquestioned in the case of the East Roman, or Byzantine Empire, but Byzantine siege warfare has received only sporadic attention, and it has been even more marginal in explaining the Islamic expansion.3 This study seeks to examine the organization and practice of siege war- fare among the major successor states of the former Roman Empire: The 1 Ward-Perkins 2006, reviewing Halsall 2003. -

COMPENDIO DOTES BETA.Pdf

Índice de Manuales Manual del Jugador Guía del Dungeon Master Manual del Jugador II Manual de Monstruos MJ2 MM El Aventurero Completo El Divino Completo El Arcano Completo El Combatiente Completo AC DC RC CC Draconomicón Especies Salvajes Héroes de Guerra Heroes of Horror D ES HG HH Faerûn: Guía del Jugador El Este Inaccesible Razas de Faerûn Escenario de Campaña GJF EI RF E Eberron: Guía del Jugador Libro de Obras Elevadas Libro de Oscuridad Vil Libris Mortis GJE OE OV LM Capítulo 1 – Presentación NOMBRE DE LA DOTE [TIPO DE DOTE] [CORRUPTA]: presentada en Heroes of Horror. Las dotes corruptas sólo Una descripción sencilla de lo que la dote hace o representa. pueden ser elegidas por aquellos que están corruptos, como se describe en el Requisitos: la puntuación mínima de característica, la dote o dotes, el apéndice. Ciertas dotes requieren una mayor corrupción que otras, o un tipo ataque base mínimo, la habilidad o el nivel de experiencia que se debe tener de corrupción específica (perversión o depravación). Cualquiera con una dote para poder adquirir esta dote. Este apartado no aparece en aquellas dotes que corrupta que reduzca su puntuación de corrupción por debajo de los carecen de requisito. Una dote puede tener más de un requisito. requisitos de la dote, pierde el acceso a esa dote. Sin embargo, no pierde la Beneficio: lo que la dote permite hacer al personaje (“tú” en la dote. No posee un espacio vacío para llenar con otra dote y recupera al descripción). Si un personaje tiene la misma dote más de una vez, sus instante el uso de la dote si alguna vez sube su nivel de corrupción al nivel beneficios no se apilan a no ser que en la descripción ponga otra cosa. -

The Emergence of the Light, Horse-Drawn Chariot in the Near-East C. 2000-1500 B.C. Author(S): P. R. S. Moorey Source: World Archaeology, Vol

The Emergence of the Light, Horse-Drawn Chariot in the Near-East c. 2000-1500 B.C. Author(s): P. R. S. Moorey Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 2, Weaponry and Warfare (Oct., 1986), pp. 196-215 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/124615 Accessed: 06-11-2015 06:35 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 141.211.4.224 on Fri, 06 Nov 2015 06:35:53 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Tlhe emergence of the light, horse-drawn chariot in the Near-East c. 2000-1500 B.C.* The recent appearance of three richly documented monographs assembling the diverse and often complex evidence for riding and traction in the pre-classical societies of the Near East and Europe (Littauer and Crouwel 1979: Crouwel 1981: Piggott 1983) provides an opportunity for reassessing a number of critical issues in the earliest history of the light, horse-drawn chariot, whose arrival in many ancient communities has long been seen as a source of significant change in politics and society. -

M. Witzel (2003) Sintashta, BMAC and the Indo-Iranians. a Query. [Excerpt

M. Witzel (2003) Sintashta, BMAC and the Indo-Iranians. A query. [excerpt from: Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Western Central Asia] (to appear in : Sino-Platonic Papers 129) Transhumance, Trickling in, Immigration of Steppe Peoples There is no need to underline that the establishment of a BMAC substrate belt has grave implications for the theory of the immigration of speakers of Indo-Iranian languages into Greater Iran and then into the Panjab. By and large, the body of words taken over into the Indo-Iranian languages in the BMAC area, necessarily by bilingualism, closes the linguistic gap between the Urals and the languages of Greater Iran and India. Uralic and Yeneseian were situated, as many IIr. loan words indicate, to the north of the steppe/taiga boundary of the (Proto-)IIr. speaking territories (§2.1.1). The individual IIr. languages are firmly attested in Greater Iran (Avestan, O.Persian, Median) as well as in the northwestern Indian subcontinent (Rgvedic, Middle Vedic). These materials, mentioned above (§2.1.) and some more materials relating to religion (Witzel forthc. b) indicate an early habitat of Proto- IIr. in the steppes south of the Russian/Siberian taiga belt. The most obvious linguistic proofs of this location are the FU words corresponding to IIr. Arya "self-designation of the IIr. tribes": Pre-Saami *orja > oarji "southwest" (Koivulehto 2001: 248), ārjel "Southerner", and Finnish orja, Votyak var, Syry. ver "slave" (Rédei 1986: 54). In other words, the IIr. speaking area may have included the S. Ural "country of towns" (Petrovka, Sintashta, Arkhaim) dated at c. -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

Languages and Migrations in Prehistoric Europe Roots of Europe Summer Seminar

Languages and migrations in prehistoric Europe Roots of Europe summer seminar 7–12 August 2018 National Museum of Denmark & the University of Copenhagen Languages and migrations in prehistoric Europe Roots of Europe summer seminar 7–10 August 2018 National Museum of Denmark Festsalen Ny Vestergade 10 Prinsens Palæ DK-1471 København K 11–12 August 2018 University of Copenhagen Faculty of Humanities (KUA) Multisalen (Room 21.0.54) Emil Holms Kanal 6 The Roots of Europe Summer Seminar Preface The Roots of Europe Research Center has its origins in a so-called Programme of Excellence funded by the University of Copenhagen and hosted by the De- partment of Nordic Studies and Linguistics. The founding members were a group of historical linguists specializing in Indo-European Studies, a disci- pline that goes back two centuries at the University of Copenhagen, to the days when the linguist and philologist Rasmus Rask (1787–1832) carried out 2 his ground-breaking research. The programme marked a new epoch in modern-day Indo-European stud- ies in that it began to incorporate the findings of archaeology and genetics in its quest to understand the prehistorical spread of the Indo-European lan- guages. This was not the first attempt to relate the many branches of the fam- Preface ily tree to material cultures and, indeed, genes. However, previous attempts were abandoned, after the field was, figuratively speaking, taken hostage by a nefarious alliance of pseudoscientific researchers and politicians around the turn and first half of the 20th century. After the Second World War, collaborations between archaeologists and linguists became rare and generally frowned upon. -

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry Under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias The last war between the Eastern Romans and the Sassanids was likely the most important of Late Antiquity, exhausting both sides economically and militarily, decimating the population, and lay- ing waste the land. In Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium, Walter Kaegi, concludes that the Romaioi1 under Herakleios (575-641) defeated the Sassanian forces with techniques from the section “Dealing with the Persians”2 in the Strategikon, a hand book for field commanders authored by the emperor Maurice (reigned 582-602). Although no direct challenge has been made to this claim, Trombley and Greatrex,3 while inclided to agree with Kaegi’s main thesis, find fault in Kaegi’s interpretation of the source material. The development of the katafraktos stands out as a determining factor in the course of the battles during Herakleios’ colossal counter-attack. Its reforms led to its superiority over its Persian counterpart, the clibonarios. Adoptions of steppe nomad equipment crystallized the Romaioi unit. Stratos4 and Bivar5 make this point, but do not expand their argument in order to explain the victory of the emperor over the Sassanian Empire. The turning point in its improvement seems to have taken 1 The Eastern Romans called themselves by this name. It is the Hellenized version of Romans, the Byzantine label attributed to the surviving East Roman Empire is artificial and is a creation of modern historians. Thus, it is more appropriate to label them by the original version or the Anglicized version of it. -

Maryland Naval Warfare Center Case Study

MARYLAND NAVAL WARFARE CENTER Customer Case Study • Simple and efficient system with reporting functionality TECHNOLOGY/PRODUCTS: • HID ProxPro® proximity readers • Cost-effective, safe alterna- tive to existing systems • HID ProxCard® II proximity card tags • HID ProxKey® II key-chain proximity tags It’s Anchors Away for Navy Base’s Access Control System The munitions group at Maryland’s Naval Surface Warfare Center was in an access control quandary. A Sign-in/out log had proved impractical and electronics were too expensive or too dangerous due to the potential of explosion. The unlikely solution came from a nearby cow pasture. Call it bovine intervention. That’s the best way to describe the solution ESTECH, an electronic security systems integrator located in Annandale, Va., selected to solve the access control quagmire served up by the munitions testing group within the U.S. Naval Surface Warfare Center in Indian Head, Md. The installation’s environment demanded a creative approach because of the frequent handling of reactive substances and volatile chemicals. Before the Navy made all the security experts they had enlisted walk the plank, ESTECH climbed aboard and righted the ship. The company devised a solution based upon a most unorthodox impetus. The result was a simple, efficient system that was also cost-effective. Job Takes Dealer to Historic U.S. Site Indian Head, the site of the Naval Surface Warfare Center, sits on a 3,500-acre peninsula in the Potomac River, 30 miles south of Washington, D.C., with a rich history of security concerns. Nowadays, this secure government facility is the center for numerous core technical capabilities for the U.S.