Russell Square a Lifelong Resource for Teaching and Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Aylsham Town 7 Miles Circular Walk

AYLSHAM TOWN 7 miles Aylsham is full of historic interest. The bustling market town bristles with charming features, including the John Soame Memorial Pump and The Black Boys coaching Inn, welcoming visitors today as it has for centuries. Humphry Repton (1752-1818), the famous landscape gardener, chose Aylsham as his final resting place. Sheringham Park, which Repton described as his ‘most favourite work’, is managed by The National Trust who are, coincidentally, Lords of the Manor of Aylsham and own Aylsham Market Place. You’ll pass Aylsham Staithe; opened in 1779 it was once the main artery to Aylsham’s agricultural industry. At its peak it carried over 1000 boats annually; mainly Norfolk wherries. The junction of river and roads, plus later railways, are crucial to the situation and importance of the town. Aylsham North, a Great Eastern Railway station, opened in 1883 only a short distance from the staithe. It quickly out-competed wherries for transporting freight. Devastating floods in 1912 destroyed bridges and locks, causing Aylsham Staithe’s final demise. The flood caused problems on the railway too. Over 200 people were stranded overnight after a train from Great Yarmouth was trapped at Aylsham North following multiple bridge collapses. Spa Lane, to the south of Aylsham, is named after the spa that existed there in the early 1700s. The mineral rich waters were considered good for health. Spa Lane can become muddy in winter. The alternative route shown, using another section along Marriott’s Way, offers a shorter, but drier, walk. A Norfolk Wherry moored at the water mill at Aylsham Staithe. -

Deification in the Early Century

chapter 1 Deification in the early century ‘Interesting, dignified, and impressive’1 Public monuments were scarce in Ireland at the begin- in 7 at the expense of Dublin Corporation, was ning of the nineteenth century and were largely con- carefully positioned on a high pedestal facing the seat fined to Dublin, which boasted several monumental of power in Dublin Castle, and in close proximity, but statues of English rulers, modelled in a weighty and with its back to the seat of learning in Trinity College. pompous late Baroque style. Cork had an equestrian A second equestrian statue, a portrait of George I by statue of George II, by John van Nost, the younger (fig. John van Nost, the elder (d.), was originally placed ), positioned originally on Tuckey’s Bridge and subse- on Essex Bridge (now Capel Street Bridge) in . It quently moved to the South Mall in .2 Somewhat was removed in , and was re-erected at the end of more unusually, Birr, in County Offaly, featured a sig- the century, in ,8 in the gardens of the Mansion nificant commemoration of Prince William Augustus, House, facing out over railings towards Dawson Street. Duke of Cumberland (–) (fig. ). Otherwise The pedestal carried the inscription: ‘Be it remembered known as the Butcher of Culloden,3 he was com- that, at the time when rebellion and disloyalty were the memorated by a portrait statue surmounting a Doric characteristics of the day, the loyal Corporation of the column, erected in Emmet Square (formerly Cumber- City of Dublin re-elevated this statue of the illustrious land Square) in .4 The statue was the work of House of Hanover’.9 A third equestrian statue, com- English sculptors Henry Cheere (–) and his memorating George II, executed by the younger John brother John (d.). -

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage

Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage London, WC1 Mixed-Use Investment Opportunity www.geraldeve.com Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage, WC1 Investment summary • Freehold • Midtown public house, retail unit and residential flat • 3,640 sq ft (338.16 sq m) GIA of accommodation • WAULT of 8.1 years unexpired • Total passing rent of £106,700 pa • Seeking offers in excess of £1,850,000 subject to contract and exclusive of VAT • A purchase at this price would reflect a net initial yield of 5.44%, assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.23% www.geraldeve.com 44 Red Lion Street & Lamb’s Conduit Passage, WC1 Midtown 44 Red Lion Street & Lamb’s Conduit Passage is located in an enviable position within the heart of London’s Midtown. Midtown offers excellent connectivity to the West End, City of London and King’s Cross, appealing to an eclectic range of occupiers. The location is typically regarded as a hub for the legal profession, given the proximity of the Royal Courts of Justice and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but has a diverse occupier base including, tech, media, banking and professional firms. The area is also home to several internationally renowned educational institutions such as UCL, King’s College London, London School of Economics and the University of Arts, London. The surrounding area attracts a range of occupiers, visitors and tourists with the Dolphin Tavern being a named location on several Midtown walking tours. The appeal of the location is derived in part from the excellent transport links but also the diverse and exciting range of local amenities and attractions on offer, including The British Museum, Somerset House, the Hoxton Hotel, The Espresso Room and the Rosewood Hotel. -

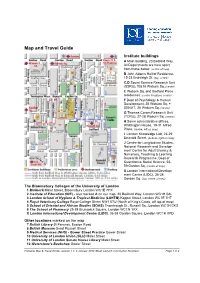

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Traffic Order 2019 the Camden (Parking Places) (CA-D) (Amendment No

The Camden (Waiting and Loading Restrictions) (Civil Enforcement Area) (Amendment No. 104) Traffic Order 2019 The Camden (Parking Places) (CA-D) (Amendment No. 29) Traffic Order 2019 The Camden (Parking Places) (CA-F) (Amendment No. 21) Traffic Order 2019 The Camden (Parking Places) (CA-P) (Amendment No. 21) Traffic Order 2019 The Camden (Parking Places) (CA-S) (Amendment No. 7) Traffic Order 2019 The Camden (Parking Places) (Dedicated Disabled) (Amendment No. 43) Traffic Order 2019 The Camden (Free Parking Places) (Disabled Persons) (Amendment No. 44) Traffic Order 2019 Notice is hereby given that the Council of the London Borough of Camden proposes to make the above Order under Sections 6, 45. 46. 49 and 124 and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended. The general nature and effect of the orders are set out below: GUILFORD STREET, WC1N: 24-hour waiting and loading restrictions to apply from a point 25.3 metres west of the western kerb line of Millman Street eastwards to a point 5.2 metres east of the eastern kerb line of Millman Street. GREAT ORMOND STREET, WC1N: 24-hour waiting restrictions to apply on the north side for a distance of approximately 5 metres west of the junction with Millman Street. MILLMAN STREET, WC1N: west side Revocation of the residents permit parking place between the junctions with Guilford Street and Millman Mews. Three disabled persons’ (Blue Badge) parking spaces to be designated between the junctions with Guilford Street and Millman Mews to operate as such on Mondays to Fridays, 8.30am – 6.30pm and on Saturdays between 8.30am and 1.30pm, maximum stay 3 hours. -

Local Restaurants

RESTAURANTS & QUICK BITES NEAR KING’S CROSS JAPANESE Itsu, 16, Brunswick Centre, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AF, open: Mon-Fr 10 am-9pm, Sat-Sun 11am-8pm, £15-£25 Hare & Tortoise, 11-13 Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AF, open: Mon- Sun 12 noon-11pm, £25-£35 PORTUGUESE Nando’s, The Brunswick Centre, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AE, open: Mon-Thu 11:30 am-10:30pm, Fr-Sat 11:30am-11:00pm, Sun 12:00-23:00, £20-£30 AMERICAN Gourmet Burger Kitchen (Brunswick), 44/46 The Brunswick Centre, Marchmont St, London WC1N 1AE, open: Mon-Tue 11am-10pm, Wed-Sun 11am-11pm, Sun 12noon- 10pm, £25-£30 ITALIAN Pizza Express, Clifton House, 93-95 Euston Road, London NW1 2RA, open: Mon-Tue, Sat-Sun 11:30am-11pm, Wed-Fr 11:30am-11:30pm, £25-£35 BRITISH Giraffe, 19-21 Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AF, open: Mon-Fr 8am- 11pm, Sat 9am-11pm, Sun 9am-10:30pm, £25-£35 Rotunda Restaurant and Bar, King’s Place, 90 York Way, King’s Cross, London N1 9AG, open: Mon-Wed, Sat 11am-11pm, Thu-Fr 11am-12 midnight, Sun 11am- 10:30pm, £40-£50 Plum & Spilt Milk, Great Northern Hotel, King’s Cross St. Pancras Station, Pancras Road, London N1C 4TB, open: Mon-Fr 7am-11pm, Sat 8am-11pm, Sun 8am-10pm, £45-£55 The Gilbert Scott, St Pancras Renaissance Hotel, Euston Rd, King’s Cross, London NW1 2AR, open: Mon-Thu lunch 12pm-2:45pm, dinner 5:30pm-9:45pm, Fr lunch 12noon- 2:45pm, dinner 5:30pm-10:45pm, Sat 12noon-10:45pm, Sun 12noon-8:45pm, £45- £55 MEXICAN Las Iguanas, 15-17, The Brunswick Centre, Marchmont St, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AF, open: Mon-Do, Sun 10am-10:30pm, Fr-Sat 10am-11:30pm, £25-£35 VIETNAMESE Cô Ba Restaurant, 244 York Way, London N7 9AG, open: Tue-Fr 12noon-3pm, 6pm- 10pm, Sat 6pm-10pm, £30-£40 ITALIAN CAFÉ Carluccio’s, 1 Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AF, open: Mon-Fr 7:30am-11:30pm, Sat 9am-11:30pm. -

Bloomsbury Sub Area 10

E N A 1 L 2 N E 9 E m 3 1 R . o 9 t 1 G 3 1 3 5 G T R N I U O L 2 C 3 R E W E O R O 4 N T B R A 1 E 1 6 6 P t o 2 PH A 4 1 7 A h R g u o r 1 8 T 58 54 1 1 PH 9 1 0 56 9 1 1 t 1 r 2 5 1 0 1 u 3 t t o o o 1 1 1 7 C 0 0 ths 6 ffi ri 2 G 2 e 1 rin he at Cycle Hire 1 6 4 o 6 t Station Listed Building 62 1 8 5 1 1 Positive Building 9 T o 74 R t D E 67 A C 16.1m RO E R N 1 4 O Sub Area 10 3 t T D o 1 G 4 Car Park 5 S N 8 3 I t o e 15.2m 8 5 K R n L R A a Y A F L A 9 W l s ' nne b D u T R b 1 R 5 a C 1 8 TON P LA A 9 AT 1 H D 5 3 2 Y Bloomsbury Sub Area 10 3 6 1 El Sub Sta 1 1 TCBs 7 t 9 E o 3 0 1 PH 2 1 5 N 1 2 5 I 7 V L HILL 1 HE RBA 5 1 1 0 t 7 r C 7 RAWFORD PASSAGE 1 3 u 1 o t 5 7 f Balle 1 2 0 o C ol 3 3 5 o ho t 4 6 8 tral Sc 8 r Cen 8 1 o o 1 t 1 8 t 5 2 7 9 c t r 5 5 1 e r 1 6 u 1 L o t o t o o t 1 o 6 t 4 e 6 5 s p o 9 u C i H l e p 2 a r T 1 h T 5 C y c lwa PH 3 1 E ai S E R 2 d 1 1 E n 6 u 3 E 0 ro 9 r g 1 6 nde R 2 t o R U o 1 T t 7 1 1 47a T S 8 4 9 1 6 2 7 o S t 1 4 PH 7b M 8 1 8 1 A 2 5 1 S 3 5 o H t House S t 3 o Printing & P h 3 9 Caslon O 5 1 1 c 0 s 1 r O 9 9 ' D t 4 7 4 r o u R 3 T London College of 9 The London Institute e o h t t A 6 1 57 Distributive Trades e 3 C C 4 Design P O n 5 t 4 a T 3 i l R PCs S n College of Art & a 4 2 S t o 0 Post Central Saint Martins i a 2 B I t A 7 KE L 5 50 t a R' 49 o t S R 22 47 O t L 48 1 4 S W o Warner House 2 24 e 4 E 8 r 6 i 1 1 4 44 L 3 5 F 2 d B L 7 I 1 W 5 F H K N 5 3 C 4 y E 40 A o Drill Tower t 42 d 8 5 E B B 4 4 K 9 5 39 0 o R t B 1 6 1 5 A L R 8 36 g to 38 2 H 6 U f & 9 T e E -

Architecture MPS

Architecture_MPS Landscape and Consumer Culture in the Design Work of Humphry Repton and Gordon Cullen: A Methodological Framework Mira Engler*,1 How to cite: Engler, M. ‘Landscape and Consumer Culture in the Design Work of Humphry Repton and Gordon Cullen: A Methodological Framework.’ Architecture_MPS, 2018, 13(1): 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.amps.2018v13i2.001. Published: 09 March 2018 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the journal’s standard double blind peer-review, where both the reviewers and authors are anonymised during review. Copyright: © 2017, The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited • DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.amps.2018v13i2.001. Open Access: Architecture_MPS is a peer-reviewed open access journal. *Correspondence: [email protected] 1 Iowa State University, USA Amps Title: Landscape and Consumer Culture in the Design Work of Humphry Repton and Gordon Cullen: A Methodological Framework Author: Mira Engler Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 13, no. 2. March 2018 Affiliation: Landscape Architecture, Iowa State University Abstract The practice of landscape and townscape or urban design is driven and shaped by consumer markets as much as it is by aesthetics and design values. Since the 1700s gardens and landscapes have performed like idealized lifestyle commodities via attractive images in mass media as landscape design and consumer markets became increasingly entangled. This essay is a methodological framework that locates landscape design studies in the context of visual consumer culture, using two examples of influential and media-savvy landscape designers: the renowned eighteenth-century English landscape gardener Humphry Repton and one of Britain’s top twentieth-century draftsmen and postwar townscape designers, Gordon Cullen. -

Camden Outdoor

Camden IS OPEN FOR BUSINESS OUTDOOR SPACES Content: The Camden Events Service supports community, corporate and 01. Britannia Junction, Camden private events in the Borough. Town / Page 02 Camden have 70 parks and open spaces available for event hire. The 02. Russell Square / Page 06 events service offers a number of untraditional, experiential and street 03. Bloomsbury Square / Page 08 locations as well as many indoor venues. 04. Great Queen Street, Covent Camden is one of London’s creative hubs, Garden / Page 10 welcoming a number of events and activities throughout the year. These include street parties, filming, street promotions, experiential 05. Neal Street, Covent Garden / marketing, sampling and community festivals. Page 12 Our parks, open spaces and venues can accommodate corporate team building days, conferences, exhibitions, comedy nights, parties, weddings, exams, seminars and training. The events team are experienced in managing small and large scale events. 020 7974 5633 [email protected] 01 Camden is open for business Highgate Hampstead Town Frognal & Fitzjohns Fortune Green Gospel Oak Kentish Town West Hampstead Haverstock Belsize Cantelowes Swiss Cottage Camden Town 01 & Primrose Hill Kilburn St Pancras & Somers Town Regents Park King’s Cross 02 Bloombury Holborn & 03 Covent Garden The Camden Events Service supports community, 04 05 corporate and private events in the Borough. Camden have 70 parks and open spaces available for event hire. The events service offers a number of untraditional, experiential and street locations as well as many indoor venues. Camden is one of London’s creative hubs, welcoming a number of events and activities throughout the year. -

Our Future in Place the Report on Consultation

THE FARRELL REVIEW of Architecture + the Built Environment OUR FUTURE IN PLACE THE REPORT ON CONSULTATION BY THE FARRELL REVIEW TEAM Contents P.2 INTRODUCTION P.5 TERMS OF REFERENCE P.6 1. EDUCATION, OUTREACH AND SKILLS P.36 2. DESIGN QUALITY P.66 3. CULTURAL HERITAGE P.83 4. ECONOMIC BENEFITS P.113 5. BUILT ENVIRONMENT POLICY P.120 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE FARRELL REVIEW THE REPORT ON CONSULTATION 1 Introduction This Review has engaged widely from the start. In that respect it set itself apart from many other government reviews and has been independent in both its methods and its means. Over the last year, the team has reached out and consulted with thousands of individuals, groups and institutions. They have been from private, public and voluntary sectors, and from every discipline and practice relating to the built environment: architecture, planning, landscape architecture, engineering, ecology, developers, agents, policymakers, local government and politicians. “We are the editors and curators in the terms of reference that were issued by the of many voices.” Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) Sir Terry Farrell CBE (see page 5). Over 200 responses were received from individuals, companies, groups and This Report on the consultation process by institutions, with many organising questionnaires the Review team, led by Max Farrell and co- for members representing over 370,000 people. ordinated by Charlie Peel, is a structured narrative of the key themes of the Review, told Third were a series of workshops hosted through the many voices of its respondents and around the country. Each of these workshops participants.