A Diplomatic Whistleblower in the Victorian Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

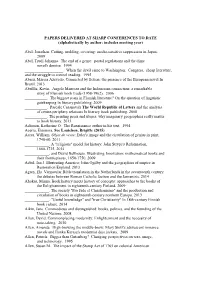

PAPERS DELIVERED at SHARP CONFERENCES to DATE (Alphabetically by Author; Includes Meeting Year)

PAPERS DELIVERED AT SHARP CONFERENCES TO DATE (alphabetically by author; includes meeting year) Abel, Jonathan. Cutting, molding, covering: media-sensitive suppression in Japan. 2009 Abel, Trudi Johanna. The end of a genre: postal regulations and the dime novel's demise. 1994 ___________________. When the devil came to Washington: Congress, cheap literature, and the struggle to control reading. 1995 Abreu, Márcia Azevedo. Connected by fiction: the presence of the European novel In Brazil. 2013 Absillis, Kevin. Angele Manteau and the Indonesian connection: a remarkable story of Flemish book trade (1958-1962). 2006 ___________. The biggest scam in Flemish literature? On the question of linguistic gatekeeping In literary publishing. 2009 ___________. Pascale Casanova's The World Republic of Letters and the analysis of centre-periphery relations In literary book publishing. 2008 ___________. The printing press and utopia: why imaginary geographies really matter to book history. 2013 Acheson, Katherine O. The Renaissance author in his text. 1994 Acerra, Eleonora. See Louichon, Brigitte (2015) Acres, William. Objet de vertu: Euler's image and the circulation of genius in print, 1740-60. 2011 ____________. A "religious" model for history: John Strype's Reformation, 1660-1735. 2014 ____________, and David Bellhouse. Illustrating Innovation: mathematical books and their frontispieces, 1650-1750. 2009 Aebel, Ian J. Illustrating America: John Ogilby and the geographies of empire in Restoration England. 2013 Agten, Els. Vernacular Bible translation in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century: the debates between Roman Catholic faction and the Jansenists. 2014 Ahokas, Minna. Book history meets history of concepts: approaches to the books of the Enlightenment in eighteenth-century Finland. -

On the Rejection of Oscar Wilde's the Picture of Dorian Gray by W. H. Smith

humanities Article On the Rejection of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray by W. H. Smith Satoru Fukamachi Faculty of Humanities, Doho University, Nagoya 453-8540, Japan; [email protected] Received: 1 September 2020; Accepted: 26 October 2020; Published: 29 October 2020 Abstract: Wilde’s only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, is widely said to have been rejected by W. H. Smith, but there is no doubt that this did not happen. The letter sent to Wilde by the publisher strongly indicates that W. H. Smith contemplated removing the July issue of Lippincott’s Magazine, but does not go so far as to say that the bookstore did. This letter is the only evidence, however, that this is not absolute. The refusal to sell is mere speculation. The fact that none of Wilde’s contemporaries mentioned the incident of The Picture of Dorian Gray that supposedly happened, while the boycott of George Moore’s Esther Waters, which was much less topical than this one, was widely reported and discussed, provides further evidence that Wilde’s work was not rejected. Given that the censorship of literary works by private enterprises was still topical in the 1890s, it is unbelievable that the rejection of Wilde’s novel would not have been covered by any newspaper. It makes no sense, except to think that such a thing did not exist at all. It is also clear that this was not the case in the 1895 Wilde trial. Wilde’s lawyer argued that the piece was not a social evil because it was sold uninterruptedly, and the other side, which would have liked to take advantage of it in any way, never once touched on the boycott. -

1822: Cain; Conflict with Canning; Plot to Make Burdett the Whig Leader

1 1822 1822: Cain ; conflict with Canning; plot to make Burdett the Whig leader; Isaac sent down from Oxford, but gets into Cambridge. Trip to Europe; the battlefield of Waterloo; journey down the Rhine; crossing the Alps; the Italian lakes; Milan; Castlereagh’s suicide; Genoa; with Byron at Pisa; Florence; Siena, Rome; Ferrara; Bologna; Venice; Congress of Verona; back across the Alps; Paris, Benjamin Constant. [Edited from B.L.Add.Mss. 56544/5/6/7.] Tuesday January 1st 1822: Left two horses at the White Horse, Southill (the sign of which, by the way, was painted by Gilpin),* took leave of the good Whitbread, and at one o’clock (about) rode my old horse to Welwyn. Then [I] mounted Tommy and rode to London, where I arrived a little after five. Put up at Douglas Kinnaird’s. Called in the evening on David Baillie, who has not been long returned from nearly a nine years’ tour – he was not at home. Wednesday January 2nd 1822: Walked about London. Called on Place, who congratulated me on my good looks. Dined at Douglas Kinnaird’s. Byng [was] with us – Baillie came in during the course of the evening. I think 1 my old friend had a little reserve about him, and he gave a sharp answer or two to Byng, who good-naturedly asked him where he came from last – “From Calais!” said Baillie. He says he begins to find some of the warnings of age – deafness, and blindness, and weakness of teeth. I can match him in the first. This is rather premature for thirty-five years of age. -

Women Writers, World Problems, and the Working Poor, C. 1880-1920 : ”Blackleg’ Work in Literature’

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Women writers, world problems, and the working poor, c. 1880-1920 : ”blackleg’ work in literature’ https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40371/ Version: Full Version Citation: Janssen, Flore (2018) Women writers, world problems, and the working poor, c. 1880-1920 : ”blackleg’ work in literature’. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London Women Writers, World Problems, and the Working Poor, c. 1880–1920: ‘“Blackleg” Work in Literature’ Flore Willemijne Janssen Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 1 Declaration I, Flore Willemijne Janssen, declare that this thesis is my own work. Where I have drawn upon the work of other researchers, this has been fully acknowledged. Date: Signed: 2 Abstract This thesis uses the published work of professional writers and activists Clementina Black and Margaret Harkness to explore their strategies for the representation of poverty and labour exploitation during the period 1880–1920. Their activism centred on the working poor, and specifically on those workers whose financial necessity forced them into exploitative and underpaid work, causing them to become ‘blacklegs’ who undercut the wages of other workers. As the generally irregular nature of their employment made these workers’ situations difficult to document, Black and Harkness sought alternative ways to portray blackleg work and workers. The thesis is divided into two parts, each comprising two chapters. -

2019 – 2020 English Literature Third Year Option Courses

2019 – 2020 ENGLISH LITERATURE THIRD YEAR OPTION COURSES (These courses are elective and each is worth 20 credits) Before students will be allowed to take one of the non-departmentally taught Option courses (i.e. a LLC Common course or Divinity course), they must already have chosen to do at least 40-credits worth of English or Scottish Literature courses in their Third Year. For Joint Honours students this is likely to mean doing one of their two Option courses (= 20 credits) plus two Critical Practice courses (= 10 credits each). 6 June 2019 SEMESTER ONE Page Body in Literature 3 Contemporary British Drama 6 Creative Writing: Poetry * 8 Creative Writing: Prose * [for home students] 11 Creative Writing: Prose * [for Visiting Students only] 11 Discourses of Desire: Sex, Gender, & the Sonnet Sequence . 15 Edinburgh in Fiction/Fiction in Edinburgh * [for home students] 17 Edinburgh in Fiction/Fiction in Edinburgh * [for Visiting Students only] 17 Fiction and the Gothic, 1840-1940 19 Haunted Imaginations: Scotland and the Supernatural * 21 Modernism and Empire 22 Modernism and the Market 24 Novel and the Collapse of Humanism 26 Sex and God in Victorian Poetry 28 Shakespeare’s Comedies: Identity and Illusion 30 Solid Performances: Theatricality on the Early Modern Stage 32 The Cinema of Alfred Hitchcock (=LLC Common Course) 34 The Making of Modern Fantasy 36 The Subject of Poetry: Marvell to Coleridge * 39 Working Class Representations * 41 SEMESTER TWO Page American Innocence 44 American War Fiction 47 Censorship 49 Climate Change Fiction -

APPENDIX 12 – ALBANY RIVERSIDE PLANNING COMMITTEE REPORT Agenda Item 7

APPENDIX 12 – ALBANY RIVERSIDE PLANNING COMMITTEE REPORT Agenda Item 7 PLANNING COMMITTEE [email protected] References: P/2016/3371 00607/T/P1 Address: 40 and 40a High Street, Brentford TW8 0DS Proposal: Demolition of existing office building and Arts Centre to provide 193 new dwellings within buildings of part 6, part 7 storeys (Class C3), with ancillary ground floor retail/cafe, hard and soft landscaping, revised vehicular access and all necessary enabling and ancillary works. Ward: Brentford This application is a Major development with a S106 agreement on Council owned land 1.0 SUMMARY 1.1 The proposal is for the demolition of the existing buildings on the site and its redevelopment to provide 193 new private dwellings alongside basement car parking, landscaping and provision of a new riverside public walkway and retail/café unit. 1.2 The scheme is considered to be a of a high design quality, providing high quality residential accommodation with limited impact on existing residents’ amenity or the local transport network. It is considered that the scheme would have less than substantial harm on nearby heritage assets, including Kew World Heritage Site and the Grade I Listed Kew Palace located on the opposite side of the River Thames. The significant public benefits of the scheme, when taken in conjunction with the delivery of a re-provided arts centre in the centre of Brentford, outweigh any perceived harm. 1.3 This application would be delivered in conjunction with the proposals for the Brentford Police Station site on Half Acre (application ref 00540/A/P6), which proposes the redevelopment of the site to facilitate the provision of a new Arts Centre and 105 new dwellings, including 60 affordable homes. -

Émile Zola, Novelist and Reformer

/ V7'6 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THE Joseph Whitmore Barry dramatic library THE GIFT or TWO FRIENDS OF Cornell University 1934 A DATE DUE PR1NTEDIN U.S. Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924088660588 EMILE ZOLA Photo by Cautin & Bcrger Emile Zola in his last days £MILE ZOLA NOVELIST AND REFORMER AN ACCOUNT OF HIS LIFE & WORK BY ERNEST ALFRED VIZETELLY ILLUSTRATED BY PORTRAITS, VIEWS, 6f FAC-SIMILES JOHN LANE: THE BODLEY HEAD LONDON £3" NEW YORK • MDCCCCIV Copyright, 1904. By JOHN LANE 1 ^ THE UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASS. , O. S. A. TO HIS MEMORY " If, upon your side, you have the testimony of your conscience, and, against you, that of the multitude, take comfort, rest assured that time will do justice.'^ — Diderot PREFACE This book is an attempt to chronicle the chief incidents in the life of the late Emile Zola, and to set out the various aims he had in view at different periods of a career which was one of the most strenuous the modern world has known. Virtually all his work is enumerated in the following pages, which, though some are given to argument and criticism, will be found crowded with facts. The result may not be very artistic, but it has been partially my object to show what a tremendous worker Zola was, how incessantly, how stubbornly, he practised the gospel which he preached. An attempt has been made also to show the growth of humani- tarian and reforming passions in his heart and mind, passions which became so powerful at last that the " novelist " in Zola seemed as nothing. -

Facts About Champagne and Other Sparkling Wines by Henry Vizetelly

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Facts About Champagne and Other Sparkling Wines, by Henry Vizetelly This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Facts About Champagne and Other Sparkling Wines Author: Henry Vizetelly Release Date: March 24, 2007 [EBook #20889] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FACTS ABOUT CHAMPAGNE *** Produced by Louise Hope and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net THE DISGORGING, LIQUEURING, CORKING, STRINGING, AND WIRING OF CHAMPAGNE (Frontispiece) FACTS ABOUT CHAMPAGNE AND OTHER SPARKLING WINES, COLLECTED DURING NUMEROUS VISITS TO THE CHAMPAGNE AND OTHER VITICULTURAL DISTRICTS OF FRANCE, AND THE PRINCIPAL REMAINING WINE-PRODUCING COUNTRIES OF EUROPE. BY HENRY VIZETELLY, Chevalier of the Order of Franz Josef. Wine Juror for Great Britain at the Vienna and Paris Exhibitions of 1873 and 1878. Author of “The Wines of the World Characterized and Classed,” &c. WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS, DRAWN BY JULES PELCOQ, W. PRATER, BERTALL, ETC., FROM ORIGINAL SKETCHES. L ONDON: WAR D, L OC K, AND C O. , S AL I S B URY S QUAR E . 1879. Shorter Table of Contents added by transcriber Table of Contents (full) I. The Origin of Champagne. II. The Vintage in the Champagne. The Vineyards of the River. III. The Vineyards of the Mountain. IV. The Vines of the Champagne and the System of Cultivation. -

Fellowships and Awards for International Students

Fellowships and Awards for International Students 1 Getting Started Application Components Award applications have a lot of moving parts. To develop a strong and compelling fellowship application, determine: Things to consider… 1. Is the funding opportunity a good fit for you, your rese arch, ambitions, study and/or personal interests? ◊ Identify funding opportunities based on “Fit” 2. Are you a good fit for the funding opportunity? (Discipline, Demographics, Travel, etc.) ◊ Organize funding search results 3. KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE - Who are the reviewers? ◊ Dedicate time and attention to prepare and/or What are they looking for (mission of the funding opportunity, criteria for review)? request application components ◊ Commit to the Writing and Revision Process 4. Typical application components (Draft, Review, Revise, Repeat, Repeat, Repeat, Repeat) ◊ Personal Statement ◊ DEADLINES - Know the application cycle for ◊ Research Proposal ◊ Curriculum Vitae (CV) or Resume each award ◊ Letters of Recommendation ◊ NOTE: Awards are typically disbursed about ◊ Timeline and Budget Justification 6-12 months after the application submission *Not all components listed are applicable for every window closes. This means that you are applying a year in advance for most awards. application* 2 3 within the Asian continent, and is open to various nationalities. This is available to pre- Scholarships, Fellowships, and Awards doctoral and post-doctoral students. Deadline: February 1 that Accept Applications from Non-US Citizens Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship and Internship Program Individuals interested in artistic and technical production, arts administration and APS/IBM Research Internship for Undergraduate Women Internships are salaried positions typically 10 weeks long at one of three IBM research community engagement. -

Gunn-Vernon Cover Sheet Escholarship.Indd

The Peculiarities of Liberal Modernity in Imperial Britain Edited by Simon Gunn and James Vernon Published in association with the University of California Press “A remarkable achievement. This ambitious and challenging collection of tightly interwoven essays will find an eager au- dience among students and faculty in British and imperial history, as well as those interested in liberalism and moder- nity in other parts of the world.” Jordanna BaILkIn, author of The Culture of Property: The Crisis of Liberalism in Modern Britain “This volume investigates no less than the relationship of liberalism to Britain’s rise as an empire and the first modern nation. In its global scope and with its broad historical perspective, it makes a strong case for why British history still matters. It will be central for anyone interested in understanding how modernity came about.” Frank TrenTMann, author of Free Trade Nation: Consumption, Commerce, and Civil Society in Modern Britain In this wide-ranging volume, leading scholars across several disciplines—history, literature, sociology, and cultural studies—investigate the nature of liberalism and modernity in imperial Britain since the eighteenth century. They show how Britain’s liberal version of modernity (of capitalism, democracy, and imperialism) was the product of a peculiar set of historical cir- cumstances that continues to haunt our neoliberal present. SIMon Gunn is a professor of urban history at the University of Leicester. JaMeS Vernon is a professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley. ConTrIBuTorS: Peter Bailey, Tony Bennett, Tom Crook, James Epstein, Simon Gunn, Catherine Hall, Patrick Joyce, Jon Lawrence, Tom Osborne, Chris Otter, Mary Poovey, Gavin Rand, John Seed, James Vernon, David Vincent Berkeley Series in British Studies, 1 Cover photo: Construction of the Royal Albert bridge, 1858 (Wikimedia Commons, source unknown). -

Sybil, Or the Two Nations

SYBIL, OR THE TWO NATIONS by Benjamin Disraeli I would inscribe these volumes to one whose noble spirit and gentle nature ever prompt her to sympathise with the suffering; to one whose sweet voice has often encouraged, and whose taste and judgment have ever guided, their pages; the most severe of critics, but -- a perfect Wife! The general reader whose attention has not been specially drawn to the subject which these volumes aim to illustrate, the Condition of the People, might suspect that the Writer had been tempted to some exaggeration in the scenes which he has drawn and the impressions which he has wished to convey. He thinks it therefore due to himself to state that he believes there is not a trait in this work for which he has not the authority of his own observation, or the authentic evidence which has been received by Royal Commissions and Parliamentary Committees. But while he hopes he has alleged nothing which is not true, he has found the absolute necessity of suppressing much that is genuine. For so little do we know of the state of our own country that the air of improbability that the whole truth would inevitably throw over these pages, might deter many from their perusal. Grosvenor-Gate, May Day, 1845. 1 BOOK ONE Chapter 1 I:1:¶1 "I'll take the odds against Caravan." I:1:¶2 "In poneys?" I:1:¶3 "Done." I:1:¶4 And Lord Milford, a young noble, entered in his book the bet which he had just made with Mr Latour, a grey headed member of the Jockey Club. -

Historic England Response on Watermans Site Proposals

LONDON OFFICE Mr Stephen Hissett Direct Dial: 020 7973 3785 London Borough of Hounslow Development Control Our ref: P00639153 The Civic Centre Lampton Road TW3 4DN 14 September 2017 Dear Mr Hissett Arrangements for Handling Heritage Applications Direction 2015 & T&CP (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015 40 AND 40A HIGH STREET (ALBANY RIVERSIDE) BRENTFORD TW8 0DS Application No 00607/T/P1 Thank you for your letter of 10 August 2017 notifying Historic England of the above application. Historic England first commented on pre-application proposals at the Waterman’s Site in August 2016. The proposals were presented internally to our regional casework review panel, and the applicants also presented to our most senior casework committee on site at Kew Gardens in September 2016. Following that meeting further advice was issued on 7 October 2016. Having been consulted on subsequent amendments to the scheme Historic England provided a third letter of advice on 4 August this year. Summary Throughout the course of our pre-application consultation we set out our serious concerns over the impact of the proposals on the setting of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, World Heritage Site, and in particular the Grade I listed Scheduled Monument of Kew Palace. The setting of the Palace and World Heritage Site is of the highest quality and is an essential part of the experience and enjoyment of this world famous site. It also plays a major part in understanding how Kew and the ‘Arcadian Thames’ played such an important role in drawing the royal court and centuries of royal, scientific, and artistic patronage to this area of London.