Five Theories of Voting Action Strategy and Structure of Psychological Explanation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christmas Story of Brunswikians Lubomír Kostroň in Our

The Christmas Story of Brunswikians Lubomír Kostroň In our country, Czechia (Bohemia) and Moravia, people bake an exclusive longish kind of Christmas cake, which is called ―vánočka‖. Vánočka is composed of three layers of dough braids: six of them are entangled together as the bottom flat layer, four are put on them, as the middle layer and then the last two on the very top. The raisins, almonds and nuts are included, of course. Since I began to collect the information, which the following story is composed of, purposefully at the Christmas time of 2017, this metaphor for the story seems to be appropriate: the individual destinies are entangled together for some time, then the next generation of folks comes in, adds to the story and in some sense continues … and so on. This way even the ideas are shared, connecting the individuals, for some time… This is the substance of this story. People, exciting ideas, work …. In Brunswik´s terminology, the focus is on wide ―distal to distal relationships‖. Therefore, the story will be composed of individual memories and impressions of those who participated – or at least of those – as far as I know – who played some significant role in the story. Now, we have to begin with the oldest layer of our story, which is on the top of the cake . As it is usual: once upon the time …. The history of Egon Brunwik´s stretches long way back. The origins of the Austrian Hungarian family of von Brunswick or de Brunswik are uncertain, though they point to the city of Braunschweig in Germany. -

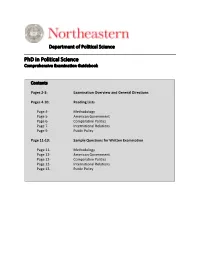

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

Hegel and the Metaphysical Frontiers of Political Theory

Copyrighted material - provided by Taylor & Francis Eric Goodfield. American University Beirut. 23/09/2014 Hegel and the Metaphysical Frontiers of Political Theory For over 150 years G.W.F. Hegel’s ghost has haunted theoretical understanding and practice. His opponents first, and later his defenders, have equally defined their programs against and with his. In this way Hegel’s political thought has both situated and displaced modern political theorizing. This book takes the reception of Hegel’s political thought as a lens through which contemporary methodological and ideological prerogatives are exposed. It traces the nineteenth- century origins of the positivist revolt against Hegel’s legacy forward to political science’s turn away from philosophical tradition in the twentieth century. The book critically reviews the subsequent revisionist trend that has eliminated his metaphysics from contemporary considerations of his political thought. It then moves to re- evaluate their relation and defend their inseparability in his major work on politics: the Philosophy of Right. Against this background, the book concludes with an argument for the inherent meta- physical dimension of political theorizing itself. Goodfield takes Hegel’s recep- tion, representation, as well as rejection in Anglo-American scholarship as a mirror in which its metaphysical presuppositions of the political are exception- ally well reflected. It is through such reflection, he argues, that we may begin to come to terms with them. This book will be of great interest to students, scholars, and readers of polit- ical theory and philosophy, Hegel, metaphysics and the philosophy of the social sciences. Eric Lee Goodfield is Visiting Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. -

Friedrich Stadler, Leslie Topp, Chair: William Johnston

1 Workshop VIENNA 1900: CURRENT DISCOURSES ON FIN-DE-SIECLE VIENNA International Center, University of New Orleans (UNO), October 24-25, 2016 SLIDE 1 Roundtable IV: Interdisciplinary Models Friedrich Stadler, Leslie Topp, Chair: William Johnston Friedrich Stadler (University of Vienna): “The Sciences and Humanities as Culture” SLIDE 2 INTRODUCTION Based on William Johnston’s path breaking trilogy of books on Austrian-Hungarian intellectual history I will focus mainly on the role of philosophy, the sciences and humanities from a trans- and interdisciplinary point of view. (Of course, the publications of Carl Schorske, Allan Janik/Stephen Toulmin, Edward Timms, David Luft, and Steven Beller and many others are to be mentioned as essential background knowledge). SLIDES 3-4: Constructive Unrest. Austrian Conference on Contemporary History Graz 2016 According to the new model of the “Long 20th Century” in Austrian history (from Habsburg Monarchy to the Republic) in general, and as applied to the history of the University of Vienna, specifically, I make a plea for this conception more or less also regarding Vienna 1900 / Fin-de-Siécle Vienna. This can be illustrated by a short report on a panel dealing with the “Paradigmenwechsel zum langen 20. Jahrhundert” (paradigm shift on the long 20th century) at the last “Österreichischer Zeitgeschichtetag” (ÖZT) in Graz, June 2016. SLIDE 5: “Wissenschaft als Kultur” (Frankfurt 1995) Following this perspective, I will argue for the need to cover all sciences (including humanities) under the umbrella of (Austro-Hungarian) culture, which seems to me the main deficit in the related historiography. Instead, the image of all sciences as an essential part of culture (Wissenschaft als Kultur) is leading up to transgressing disciplinary boundaries. -

Creative Personality and Social Risk-Taking Predict Political Party Affiliation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library THE ‘RIGHT’ SIDE OF CREATIVITY 2 The ‘right’ side of creativity: Creative personality and social risk-taking predict political party affiliation Vaibhav Tyagi University of Plymouth and Queen Margaret University Yaniv Hanoch University of Plymouth Becky Choma Ryerson University Susan L Denham University of Plymouth This research was funded by the Marie Curie Initial Training Network FP7-PEOPLE-2013- ITN, grant number 604764. Corresponding author: Vaibhav Tyagi, Marie Curie Fellow, University of Plymouth, UK, PL4 8DR E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +44-7440125590 THE ‘RIGHT’ SIDE OF CREATIVITY 3 Abstract Factors that predict political party affiliation are of particular importance in research due to the wider implications in politics and policy making. Extending this line of work, the idea that creativity predicts party affiliation was tested using two conceptualizations of creativity: creative personality and creative ideation. Participants (N = 406) based in the US completed measures of creativity, socio-political attitudes, domain specific risk-taking and indicated their party affiliation. Results revealed a significant link between creative personality and political party affiliation. Furthermore, in addition to the socio-political attitudes, this link was explained, in part, by individuals’ social risk-taking. Specifically, individuals with higher scores on creative personality were more likely to affiliate to the Democratic party, whereas the reverse was true for affiliation to the Republican party. This article provides new insights into factors that predict political party affiliation and presents wider social implications of the findings. -

BEHAVIORAL and POST BEHAVIORAL APPROACH to POLITICAL SCIENCE Sunita Agarwal1 and Prof

ISSN: 2455-2224 Contents lists available at http://www.albertscience.com ASIO Journal of Humanities, Management & Social Sciences Invention (ASIO-JHMSSI) Volume 1, Issue 1, 2015: 18-22 BEHAVIORAL AND POST BEHAVIORAL APPROACH TO POLITICAL SCIENCE Sunita Agarwal1 and Prof. S K Singh2 1Govt. College, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India 2Department of Political Science, Govt. College, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT The Behaviourailsts had laid too a great deal significance on value-free research. Review Article History In fact it was one of their essential points. They stood for value neutrality in research at all levels. Values for all practical purposes were out of their consideration. Post Behaviourailsts however, did not agree with this perspective Corresponding Author: and stressed on value loaded political Science. According to them all information Sunita Agarwal† stands on values and that unless value is considered as the basis of knowledge there is every threat that knowledge will become meaningless. They are of the view that in political research values have big role to play. The behaviouralists Govt. College, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India argue that science had some ideal commitments and that behaviouralism shared these ideal commitments of science. This thesis of the behaviouralists is not acceptable to the post-behaviouralists. They think that the technical research and scientific knowledge pursued by the behaviouralists should not be cut off from the realities of life. It should be related to vital social problems and aim at solving some problems. It is a reform movement of Behaviouralism which appreciates the work done by Behaviourailsts in developing tools, techniques and methods of research but wish that those should be used for the good of the society. -

Voting Behaviour in India and Its Determinants

Voting Behaviour in India and Its Determinants Dr. Telani Meena Horo, Associate Professor & Head Dept. of Political Science Magadh Mahila College, P.U Email: [email protected] Topic: Voting Behaviour in India Subject: Political Science Course: B.A III Paper: VII Introduction „Voting‟ is one of the most commonly used terms in contemporary age of democratic politics. The ever increasing popularity of democratic theory and practice has even made this term a household name. In democratic systems, and their number is quite large and even increasing, each adult citizen uses „voting‟ as a means for expressing his approval or disapproval of governmental decisions, policies and programmers of various political parties and the qualities of the candidates who are engaged in the struggle to get the status of being the representatives of the people. In a limited way voting refers to the function of electing representatives by casting votes in elections. However, in broad terms, as Richaed Rose and Harve Massavir point out, voting covers as many as six important functions:- 1. It involves individual‟s choice of governors or major governmental policies; 2. It permits individuals to participate in a reciprocal and continuing exchange of influence with office- holders and candidates; 3. It contributes to the development or maintenance of an individual‟s allegiance to the existing constitutional regime; 4. It contributes to the development or maintenance of a voter‟s disaffection from existing constitutional regime; 5. It has emotional significance for individuals; and 6. For some individuals it may be functionless i.e devoid of any emotional or political significant personal consequences. -

From Modernism to Messianism: Liberal Developmentalism And

From Modernism to Messianism: Liberal Developmentalism and American Exceptionalism1 Following the Second World War, we encounter again many of the same developmental themes that dominated the theory and practice of imperialism in the nineteenth century. Of course, there are important differences as well. For one thing, the differentiation and institutionalization of the human sciences in the intervening years means that these themes are now articulated and elaborated within specialized academic disciplines. For another, the main field on which developmental theory and practice are deployed is no longer British – or, more broadly, European – imperialism but American neoimperialism. At the close of the War, the United States was not only the major military, economic, and political power left standing; it was also less implicated than European states in colonial domination abroad. The depletion of the colonial powers and the imminent breakup of their empires left it in a singular position to lead the reshaping of the post-War world. And it tried to do so in its own image and likeness: America saw itself as the exemplar and apostle of a fully developed modernity.2 In this it was, in some ways, only reproducing the self-understanding and self- regard of the classical imperial powers of the modern period. But in other ways America’s civilizing mission was marked by the exceptionalism of its political history and culture, which was famously analyzed by Louis Hartz fifty years ago.3 Picking up on Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that Americans were “born equal,” Hartz elaborated upon the uniqueness of the American political experience. -

Coming in the NEXT ISSUE

Association News contributors to the international scientific DBASSE can be accessed at http://sites. community. Nearly 500 members of the nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/index. Coming NAS have won Nobel Prizes” (See http:// htm. Presiding over DBASSE presently nasonline.org/about-nas/mission). is political scientist Kenneth Prewitt. in the For the past century and a half, mem- Scholars who are not NAS members also NEXT bers have investigated and responded to regularly participate as members of NAS questions posed by our national leaders committees, and we urge all political sci- ISSUE as a form of service to the nation without entists to give serious consideration to financial recompense. As Ralph Cicerone, these requests. A preview of some of the articles in the president of the NAS, never fails to relate The discussion at this year’s meeting April 2014 issue: to new members at the annual installation of NAS-member political scientists at ceremony, while our advice is often solic- the APSA convention centered on how to SYMPOSIUM ited—its first report to the Lincoln admin- effectively transmit the best social science US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION istration addressed whether our country knowledge to the government through FORECASTING should adopt the metric system, and sent the NRC. One issue facing the NRC in Michael Lewis-Beck and back a consensus “yes” answer—this ad- general and the DBASSE in particular Mary Stegmaier, guest editors vice is not always followed. Scientific is that by charter the NAS is not permit- FEATURES objectivity is the goal of the Academy, not ted to solicit contracts from government political advocacy. -

Ithe Emporia State Studies

ITHE EMPORIA STATE STUDIES 0 THE GRADUATE PUBLICATION OF THE EMPORIA STATE UNIVERSITY ' .w L'.;;q bm bm mF. Parsons, Behavioralism, and the ResponsibilitvJ Walter B. Roettger EMPORIA STATE UNIVERSITY EMPORIA, KANSAS J Parsons, Behavioralism, and the Notion of Responsibility Walter B. Roettger Volume XXV Spring, 1977 Number 4 THE EMPORIA STATE RESEARCH STUDIES is published quarterly by The School of Graduate and Frofessional Studies of the Emporia State University, 1200 Commercial St., Emporia, Kansas, 66801, Entered as second-class matter September 16, 1952, at the post office at Emporia, Kansas, llnder the act of Angust 24, 1912. Postage paid at Emporia, Kansas. EMPORIA STATE UNIVERSITY EMPORIA, KANSAS JOHN E. VISSER President of tlle University SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES HAROLD DURST, Dean EDITORIAL BOARD WILLIAMH. SEJLER,Profezsor of History and Chirporson, Division of Social Sciences CHARLESE. WALTON,Professor of English and Chairperson of Department GREEND. WYRICK,Professor of English Editor of this Issue: WILLIAMH. SEILER Papers published in this periodical are written by faculty members of the Emporia- State University and by either undergraduate or graduate students whose studies are conducted in residence under the supervision of a faculty member of the University. , r,l-v-a PROCESSBNB APH eg 3d~ "Statement required by the Act of October, 1962; Section 4369, Title 39, United States Code, showing Ownership, Management and Circula- tion." The Emporia State Research Studies is published quarterly. Edi- torial Office and Publication Office at 1200 Commercial Street, Emporia, Kansas. (66801). The Research Studies is edited and published by the Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas. A complete list of all publications of The Emporio State Research Studies is published in the fourth number of each volume. -

The Place of Egon Brunswik in the History of Psychology*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Psychology Faculty Publications Psychology 1987 From Act Psychology to Problematic Functionalism: The lP ace of Egon Brunswik in the History of Psychology David E. Leary University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/psychology-faculty- publications Part of the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Leary, David E. "From Act Psychology to Problematic Functionalism: The lP ace of Egon Brunswik in the History of Psychology." Psychology in Twentieth-Century Thought and Society. Ed. Mitchell G. Ash and William Ray Woodward. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987. 115-42. Print. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 5 FROM ACT PSYCHOLOGY TO PROBABILISTIC FUNCTIONALISM: THE PLACE OF EGON BRUNSWIK IN THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY* DAVIDE. LEARY In the coming years, Egon Brunswik will hold an ever increasingly significant and important position in the history of psychology. (from Edward C. Tolman's eulogy, 1956) Despite Tolman's prediction, Egon Brunswik's place in the history of psy chology has yet to be firmly established. Although his name and his con cepts are frequently invoked, they are rarely used in defense of positions that he would have recognized as his own. And although most contem porary psychologists have failed to comprehend either the details or the underlying rationale of his psychological theory, historians of psychology have done even less to clarify the context, development, and import of his life and work.' This neglect is unfortunate.