Bigdeh Shesh (Paperback)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

י Three Steps to Father's House

בס“ד Parshat Bo 8 Shevat, 5777/February 4, 2017 Vol. 8 Num. 22 This issue of Toronto Torah is dedicated by Rochel and Jeffrey Silver נ“י in honour of the birth of their granddaughter Faigy Rivka Three Steps to Father’s House Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner Over a two-week period our ancestors To Father’s House works on several Seen in this light, the Exodus requires were told how to prepare for our levels, one of which is a parable for our that we be identified as the rightful national Exodus. Those commands, departure from Egypt. As the Talmud heirs of Avraham and Sarah, to merit recorded in our parshah, described (Sotah 11a) describes, our labour in that return home. This is the role of three activities: Egypt was perpetual and unrewarding, the three preparatory activities outlined Designation and sacrifice of the and we shared the protagonist’s sense in our parshah: korban pesach (Shemot 12:1-6); of not belonging. Suffering made us long Circumcision was Avraham’s mitzvah, Placement of blood from the korban for the house of our Father, and we left and it became the mark of the Jew. pesach on the entrances of their in haste. (Shemot 12:11) We displayed Korbanot were a hallmark of Avraham homes (12:7, 21-23); great ambivalence, though, en route to and Sarah, who built altars each time Circumcision of all males (12:43-50). our land; we even claimed that we had they settled a new part of Canaan. been better off in Egypt. The end of the Placement of blood from the korban We could view these three activities as book of Yehoshua (24:2-4) is part of the pesach marks the structure as a elements of the korban pesach. -

The Jewish Observer L DR

CHESHVAN, 5738 I OCTOBER 1977 VOLUME XII, NUMBER 8 fHE EWISH SEVENTY FIVE CENTS "Holocaust" - a leading Rosh Yeshiva examines the term and the tragic epoch it is meant to denote, offering the penetrating insights of a Daas Torah perspective on an era usually clouded with emo tion and misconception. "Holocaust Literature" - a noted Torah educator cuts a path through ever-mounting stacks of popular and scholarly works on "Churban Europe," highlighting the lessons to be learned and the pitfalls to be avoided. THE JEWISH BSERVER in this issue "Holocaust" - A Study of the Term, and the Epoch it is Meant to Describe, from a discourse by Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner K"t:l•7w. translated by Chaim Feuerman and Yaakov Feitman ......... .3 Dealing With "Ch urban Europa", THE JEWISH OB.SERVER is publi$ed a review article by Joseph Elias .................................................... 10 monthly, excePt July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman St., New York, N.Y. Thumb Prints, Simcha Bunem Unsdorfer r, .. , ................................ 19 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N.Y. Subscription: Torah Ambassadors at large $7.50 per year; Two years, $13.00; Three years, $18.00; outside of the I. Bringing Torah to the Valley, Moshe Turk ....................... 22 United States $8.50 per year. II. The Mexico City Junket, Single copy seventy~five cents. Printed in the U.S.A. Suri Rosenberg and Rochel Zucker ........................ 25 Letters to the Editor ............................................................................ 30 RABBI N1ssoN WotrJN Editor Subscribe ------Clip.andsave------- Editorial Board The Jewish Observer l DR. ERNST L. BODENHEIMER Chairman Renew 5 Beekman Street/ New York, N.Y. -

Rav Yisroel Abuchatzeira, Baba Sali Zt”L

Issue (# 14) A Tzaddik, or righteous person makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. (Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach; Sefer Bereishis 7:1) Parshas Bo Kedushas Ha'Levi'im THE TEFILLIN OF THE MASTER OF THE WORLD You shall say it is a pesach offering to Hashem, who passed over the houses of the children of Israel... (Shemos 12:27) The holy Berditchever asks the following question in Kedushas Levi: Why is it that we call the yom tov that the Torah designated as “Chag HaMatzos,” the Festival of Unleavened Bread, by the name Pesach? Where does the Torah indicate that we might call this yom tov by the name Pesach? Any time the Torah mentions this yom tov, it is called “Chag HaMatzos.” He answered by explaining that it is written elsewhere, “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li — I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine” (Shir HaShirim 6:3). This teaches that we relate the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and He in turn praises us. So, too, we don tefillin, which contain the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and HaKadosh Baruch Hu dons His “tefillin,” in which the praise of Klal Yisrael is written. This will help us understand what is written in the Tanna D’Vei Eliyahu [regarding the praises of Klal Yisrael]. The Midrash there says, “It is a mitzvah to speak the praises of Yisrael, and Hashem Yisbarach gets great nachas and pleasure from this praise.” It seems to me, says the Kedushas Levi, that for this reason it says that it is forbidden to break one’s concentration on one’s tefillin while wearing them, that it is a mitzvah for a man to continuously be occupied with the mitzvah of tefillin. -

Exile and Exodus 2 the Kabbalist Haggadah: a Handbook of the Seder

Exile and Exodus 2 The Kabbalist Haggadah: A Handbook of the Seder The Exile of Da’at – Knowing In order to understand the meaning of Passover, celebrating the Exodus from Egypt, we must be clear about the meaning of the Egyptian exile. It was, to use the terminology of the Kabbalah, ‘The Exile of Knowing.’ The Hebrew word for ‘Knowing’ is Da’at - ,gs. Of all the trees in the Garden of Eden, one was forbidden to Adam. In the text of Genesis (2 :9), it is named the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, the Tree of Da’at of Tov and Ra. In the simplest of terms, eating of the Tree of Knowledge precipitated a crisis in the world - it became and remains impossible to separate good and evil absolutely. Since the time of the eating, good and evil are mingled, confused and often indistinguishable. An example of the confusion that prevails: In Ger- many between the years 1933-45, cruelty toward animals was considered a hei- nous crime, and progressively harsher laws were passed to punish it. What can one say to such a statement? Is any part of it good or bad? Is the good not inex- tricably confused with the evil? Maimonides, in his monumental work on Jewish Law (Hilchoth Teshuvah 5:5) discusses ‘Knowing’ both in the divine and human spheres. If you ask: Since God knows everything, does He have prior knowledge of who will be virtuous and who will be evil, or does God not know? If God knows someone will be virtuous is it possible for him not to be so? If you say that God knows the person will be virtuous but the possi- bility remains that he will be evil, is there not something confused about God’s knowledge? Know, the answer to this question measures longer than the world, broader than the ocean. -

Vayikra-Bulletin-5780

בס'' ד בס''ד SHABBAT SCHEDULE WEEKLY SCHEDULE Minha 6:05pm Kahal Kadosh, due to the unfortunate SUNDAY Shir Hashirim: 6:20pm Shaharit: 6:30am spread of the Corona Virus in our areas, Candle Lighting: 7:17pm the Bet Hakenesset is Closed for Shaharit #2 8:00am Second Minha 7:20pm Minha/Arvit 7:25pm Services. Hashem should speedily remove Shaharit Netz Minyan: 6:20am Followed by Teenager Program Shaharit: 8:30am from us this pandemic and cure all of Am & Mishnayot In Recess Yisrael Amen. Youth Minyan: Recess MONDAY TO FRIDAY Zeman Keriat Shema 9:46am We have a few daily Shiurim on Zoom. nd Shiur Recess 2 Zeman Keriat Shema 10:20am Please take advantage & Zoom in to Shaharit 6:30am Daf Yomi Marathon Recess what’s important in life! Hodu Approx: 6:50am Shiur Recess Shaharit #2 Recess Minha: 6:55pm The Pesah Guide is already ready and all Daf Yomi 7:45am Followed by Seudat Shelishit, Pesah info & Mechirat Hametz forms Children’s/Teenager Program, & Arvit Minha 7:25pm Shabbat Ends: 8:17pm can be found on our Website! Arvit 8:15pm Shiur Hilchot Pesah 8:30pm Rabbenu Tam 8:48pm We would like to remind our Kahal Kadosh to please Donate wholeheartedly towards our Beautiful Kehila. Anyone interested in donating for any occasion, Avot Ubanim $120, Kiddush $350, Seudat Shelishit $275, Weekly Bulletin $150, Weekly Daf Yomi $180, Daf Yomi Masechet $2500, Yearly Daf Yomi $5000, Weekly Breakfast $150, Daily Learning $180, Weekly Learning $613, Monthly Rent $3500, & Monthly Learning $2000, Please contact the Board Thanking you in advance for your generous support. -

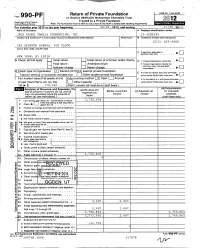

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545 -0052 Fonn 990 -PFI or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Sennce Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/01 , 2012 , and endii 11/30. 2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMT FAMILY FOUNDATION. INC. 13-3202295 Number and street ( or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) (212) 629-9600 463 SEVENTH AVENUE, 4TH FLOOR City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is , q pending , check here . NEW YORK, NY 10018 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ izations . check here El Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name chang e computation . • • • • • • . H Check type of organization X Section 501 ( cJ 3 exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507(bxlXA ), check here . Ill. El I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accountin g method X Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col. (c), line 0 Other ( specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ under section 507(b )( 1)(B), check here 16) 10- $ 17 0 , 2 4 0 . -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Matot of Bnei Yisrael? 2

Dear Youth Directors, Youth chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI is excited to continue our very successful Parsha Nation Guides. I hope you’re enjoying and learning from Parsha Nation as much as we are. Putting together Parsha Nation every week is indeed no easy task. It takes a lot of time and effort to ensure that each section, as well as each age group, receives the attention and dedication it deserves. We inspire and mold future leaders. The youth leaders of Young Israel have the distinct honor and privilege to teach and develop the youth of Young Israel. Children today are constantly looking for role models and inspirations to latch on to and learn from. Whether it is actual sit-down learning sessions, exciting Parsha trivia games, or even just walking down the hall to the Kiddush room, our youth look to us and watch our every move. It’s not always about the things we say, it’s about the things we do. Our children hear and see everything we do whether we realize it or not. This year we are taking our Youth Services to new heights as we introduce our Leadership Training Shabbaton. This engaging, interactive shabbaton will give youth leaders hands on experience and practical solutions to effectively guide your y outh department. Informal education is key. What the summer shows us as educators is that informal education can deliver better results and help increase our youth’s connection to Hashem. More and more shuls are revamping their youth program to give their children a better connection to shul and to Hashem. -

Chinuch’= Religious Education of Jewish Children and Youngsters

‘Chinuch’= Religious Education of Jewish Children and Youngsters Prof. Rabbi Ahron Daum teaches his youngest daughter Hadassah Yemima to kindle the Chanukah-lights during a family vacation to Israel, 1997 1 ‘Chinuch’ =Jewish Religious Education of Children Including: Preparation Program for ‘Giyur’ of Children: Age 3 – 18 1. ‘Chinuch’ definition: The Festival of Chanukah probably introduced the word “Chinuch” to Judaism. This means to introduce the child to Judaism and to dedicate and inaugurate him in the practice of ‘Mitzvot’. The parents, both mother and father, are the most important persons in the Jewish religious education of the child. The duty of religious education already starts during the period of pregnancy. Then the child is shaped and we should influence this process by not speaking ugly words, shouting, listening to bad music etc, but shaping it in a quiet, peaceful and harmonious atmosphere. After being born, the child already starts its first steps with “kashrut” by being fed with mother’s milk or with kosher baby formula. 2 The Midrash states that when the Jewish people stood at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah, they were asked by G-d for a guarantee that they would indeed observe the Torah in the future. The only security which God was willing to accept, concludes the Midrash, was the children of the Jewish people. This highlights the overwhelming significance of ‘Chinuch’. The duty to train children in ‘Mitzvah’-observance is rabbinic in nature. Parents are rabbinic ally obligated to make sure that their children observe the Torah, so that they will be accustomed to doing this when they reach the age of adulthood. -

Divrei Torah, Present- Hopeful Sign

, t'-1==··1<<~.-,.~~ . ,>.,.~... a>·>F Haolam, the most trusted name in Cholov Yisroel Kosher Cheese. A reputation earned through 25 years of scrupulous devotion to quality and kashruth. With 12 delicious varieties. Hao!am, a tradition you'll enjoy keeping. All Haolam cheese products are made in the U.S.A. under the strict rabbinical supervision of: The Rabbinate of K'hal Adath Jeshurun 1~-:v1 Washington Heights. NY Cholov l'isroel THURM BROS. WORLD CHEESE CO. INC. BROOKLYN.NY 11232 I The Thurm Families wish Kial Yisroel a nn'V1 1'\V:J ln If it has no cholesterol, a better than-butter flavor, and a reputation for kashruth you can trust... It has to be 111 I the new, improved parve I a I unsalted margarine I~~ I Under the strict Rabbinical supervision of K'hal Adas jeshurun, NY. COMMERCIAL QUALITY • INSTITUTIONAL & RESIDENTIAL • WOOD • STEEL • PLASTIC • SWINGS • SLIDES • PICNIC TABLES • SCHOOL & CAMP EQUIPMENT • BASKETBALL SYSTEMS • RUBBER FLOORING • ETC. • Equipment meets or exceeds all ASTM and CPSC safety guidelines • Site planning and design services with state-of-the-art Auto CAD • Stainless steel fabrication for I ultimate rust resistance New Expanded I Playground Showroom! I better 5302 New Utrecht Avenue• Brooklyn, NY 11219 health Phone: 718-436-480 l INSHABBOS Swimmhlg in •'".:n.o Night Hike to Sattaf Heruliya Beach MeJava Malka nan 11 July 19 nrin"1' INSHABBOS 11'#.:nJI Brieflng & Packing for South nrin t:> Aug.2 OFFSHABBOS Special Visit To Spurts & Field Day Yad Vashem! in "l/'lfl' TJ :i.K 0 Aug. 13 :i.K t Aug. -

Shatnez in Turkish Talleisim: What Happened and the Lessons to Be Learned Interview with Rabbi Yosef Sayagh

Article written by the Yated Ne’eman 3 Adar 5769, Feb 27th ‘09 Shatnez in Turkish Talleisim: What Happened and the Lessons to Be Learned Interview With Rabbi Yosef Sayagh Recently, a significant number of ‘Turkish’ talleisim made in Tunisia were found to contain shatnez, while yet others were found not be 100% wool. When this first came to light, not all the details were clear and we were advised to refrain from reporting the story until all the facts emerged. We sat down with Rabbi Yosef Sayagh of the Lakewood Shatnez Laboratory, who provided background information, as well as some of the relevant halachic details, regarding the recent find. • • • • • Yated: Can you provide a basic background of what was found and which talleisim are/were affected? Rabbi Sayagh: The only talleisim, which are an issue, are ‘Turkishe’talleisim. First let us briefly discuss the history of Turkishetalleisim. Turkishe talleisim have been made from wool that comes from Turkey. The reason why, historically,Chassidim have used talleisim with Turkish wool is because Turkey was a country that was known not to have any linen. Thus, if there was no linen around, the wool was obviously pure ofshatnez, and for that reason they preferred to use talleisim made of Turkish wool. The Belzer Rebbe, the Sar Shalom, was quoted as saying that after thechurban Bais Hamikdosh, the maalos, the qualities, of the land of Eretz Yisroel, became dispersed to other areas of the world. The mountains, for example, went to Switzerland. Theshvach, quality, of wool, he said, went to Turkey. That is another reason why some Chassidim preferred to use Turkishe talleisim.