The Benedict Option Through American Eyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Identity College Guide

NATIONAL CATHOLIC REGISTER, SEPTEMBER 7, 2014 C1 The Register’s 10th Annual CATHOLIC IDENTITY 2014 COLLEGE GUIDE C2 AQUINAS COLLEGE C2 THE AUGUSTINE INSTITUTE C2 AVE MARIA UNIVERSITY C2 BELMONT ABBEY COLLEGE C2 BENEDICTINE COLLEGE C2 CAMPION COLLEGE AUSTRALIA his National Catholic Register C4 THE CatHOLIC DIStaNCE UNIVERSITY resource is made possible through C4 THE CatHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERIca the cooperation of bishops, college C4 CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE T presidents, our benefactors and our C4 COLLEGE OF SAINT MARY advertisers. This year, 38 schools went on C4 COLLEGE OF ST. MARY MAGDALEN record in answer to these questions: C4 DESALES UNIVERSITY C4 DONNELLY COLLEGE C4 FRANCIScaN UNIVERSITY OF StEUBENVILLE C5 HOLY APOSTLES COLLEGE AND SEMINARY C5 HOLY CROSS COLLEGE C5 HOLY SPIRIT COLLEGE C5 INSTITUTE FOR THE PSYCHOLOGIcaL Text of the questionnaire we sent to Catholic colleges. ScIENCES C5 INTERNatIONAL THEOLOGIcaL 1. Did the president make the public “Profession of Faith” and INSTITUTe — sCHOOL OF catHOLIC take the “Oath of Fidelity”? THEOLOGY 2. Is the majority of the board of trustees Catholic? C5 PONTIFIcaL JOHN PaUL II INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES ON MARRIAGE AND FAMILY at 3. Is the majority of the faculty Catholic? THE catHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERIca 4. Do you publicly require all Catholic theology professors to have C6 JOHN PAUL THE GREat catHOLIC UNIVERSITY the mandatum? C6 LIVING WatER COLLEGE 5. Did all Catholic theology professors take the “Oath of OF THE ARTS Fidelity”? C6 MADONNA UNIVERSITY 6. Do you provide daily Mass and posted times (at least weekly) for C6 MARYVALE INSTITUTE individual confession? C6 mOUNT ST. MARy’S 7. -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Contents • Abbreviations • International Education Codes • Us Education Codes • Canadian Education Codes July 1, 2021

CONTENTS • ABBREVIATIONS • INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES • US EDUCATION CODES • CANADIAN EDUCATION CODES JULY 1, 2021 ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN PROVINCES PROVINCES PROVINCES AL ALABAMA OH OHIO AK ALASKA OK OKLAHOMA CANADA AS AMERICAN SAMOA OR OREGON AB ALBERTA AZ ARIZONA PA PENNSYLVANIA BC BRITISH COLUMBIA AR ARKANSAS PR PUERTO RICO MB MANITOBA CA CALIFORNIA RI RHODE ISLAND NB NEW BRUNSWICK CO COLORADO SC SOUTH CAROLINA NF NEWFOUNDLAND CT CONNECTICUT SD SOUTH DAKOTA NT NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DE DELAWARE TN TENNESSEE NS NOVA SCOTIA DC DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TX TEXAS NU NUNAVUT FL FLORIDA UT UTAH ON ONTARIO GA GEORGIA VT VERMONT PE PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND GU GUAM VI US Virgin Islands QC QUEBEC HI HAWAII VA VIRGINIA SK SASKATCHEWAN ID IDAHO WA WASHINGTON YT YUKON TERRITORY IL ILLINOIS WV WEST VIRGINIA IN INDIANA WI WISCONSIN IA IOWA WY WYOMING KS KANSAS KY KENTUCKY LA LOUISIANA ME MAINE MD MARYLAND MA MASSACHUSETTS MI MICHIGAN MN MINNESOTA MS MISSISSIPPI MO MISSOURI MT MONTANA NE NEBRASKA NV NEVADA NH NEW HAMPSHIRE NJ NEW JERSEY NM NEW MEXICO NY NEW YORK NC NORTH CAROLINA ND NORTH DAKOTA MP NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS JULY 1, 2021 INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES International Education RN/PN International Education RN/PN AFGHANISTAN AF99F00000 CHILE CL99F00000 ALAND ISLANDS AX99F00000 CHINA CN99F00000 ALBANIA AL99F00000 CHRISTMAS ISLAND CX99F00000 ALGERIA DZ99F00000 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS CC99F00000 ANDORRA AD99F00000 COLOMBIA -

Donnelly College Faculty & Staff

TABLE OF CONTENTS Official Email Address ...................... 18 Peer-to-Peer Policy .......................... 18 Smoking Policy ................................ 18 About Donnelly College ............................ 3 Student Identification ....................... 18 Mission ............................................... 3 Visitors on Campus Policy ............... 18 Vision Statement ................................ 3 Voter Registration ............................ 19 Donnelly’s Values .............................. 3 Weapons Free Campus Policy ........ 19 Accreditation ...................................... 3 Academic Policies ................................... 20 Memberships ..................................... 4 Academic action............................... 20 Philosophy of General Education ...... 4 Academic Dishonesty ...................... 20 Academic Calendar 2018-2019 ................. 4 Admissions Policies ................................. 5 Academic Honors ............................ 21 Registration Procedures .................... 5 Academic Probation/Suspension .... 22 Admissions deadline .......................... 5 Attendance Policy ............................ 22 Transcripts for Admissions ................. 5 Changing Course Schedules ........... 22 Foreign Education Transcripts ........... 5 Class Cancellation ........................... 22 Placement Testing ............................. 5 Class Standing ................................. 22 Placement Policies ............................. 6 Course Audit ................................... -

VISITATION POLICIES at U.S. CATHOLIC COLLEGES by Adam Wilson February 2016

VISITATION POLICIES AT U.S. CATHOLIC COLLEGES by Adam Wilson February 2016 Summary This study of campus policies at Catholic colleges in the United States finds that the vast majority permit students of the opposite sex to visit campus bedrooms behind closed doors until late at night—and on many campuses, visitation is allowed without any hour limitation. When compared to a selection of devout Protestant and nondenominational Christian colleges, a similar selection of Catholic colleges has more relaxed policies pertaining to opposite-sex visitation in student bedrooms. About the Author Adam Wilson is Managing Editor of The Newman Guide to Choosing a Catholic College and Director of Communications at The Cardinal Newman Society. All of The Cardinal Newman Society’s research and analysis, including this paper, is available online on the Society’s website at www.CardinalNewmanSociety.org. Copyright © 2016 The Cardinal Newman Society. Permission to reprint is hereby granted provided no modifications are made to the text and it is identified as a publication of The Cardinal Newman Society. Note: The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Cardinal Newman Society. The Cardinal Newman Society 9720 Capital Court Suite 201 Manassas, Virginia 20110 703/367-0333 [email protected] The Cardinal Newman Society Visitation Policies at U.S. Catholic Colleges Visitation Policies at U.S. Catholic Colleges by Adam Wilson Introduction his report presents the results from a Cardinal Newman Society study of the visitation T policies in student residences at residential Catholic colleges, not including seminaries, in the United States.1 Data used in the report was collected during the summer of 2015. -

The Gazetteer of the United States of America

THE NATIONAL GAZETTEER OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA KANSAS 1984 THE NATONAL GAZETTEER OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA KANSAS 1984 Frontispiece Harvesting wheat in Kansas. Sometimes called the Wheat State, Kansas is the leading producer of grain in the United States. Its historical and cultural association with the land is reflected in such names as Belle Plaine, Pretty Prairie, Richfield, Agricola, Grainfield, Feterita, and Wheatland. THE NATIONAL GAZETTEER OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA KANSAS 1984 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1200-KS Prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey in cooperation with the U. S. Board on Geographic Names UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE:1985 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Donald Paul Model, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES BOARD ON GEOGRAPHIC NAMES Robert C. McArtor, Chairman MEMBERS AS OF DECEMBER 1984 Department of State ——————————————————————————————— Sandra Shaw, member Jonathan T. Olsson, deputy Postal Service ——————————————————————————————————— Eugene A. Columbo, member Paul S. Bakshi, deputy Department of the Interior ———————————————————————————— Rupert B. Southard, member Solomon M. Long, deputy Dwight F. Rettie, deputy David E. Meier, deputy Department of Agriculture———————————————————————————— Sotero Muniz, member Lewis G. Glover, deputy Donald D. Loff, deputy Department of Commerce ————————————————————————————— Charles E. Harrington, member Richard L. Forstall, deputy Roy G. Saltman, deputy Government Printing Office ———————————————————————————— Robert C. McArtor, member S. Jean McCormick, deputy Library of Congress ———————————————————————————————— Ralph E. Ehrenberg, member David A. Smith, deputy Department of Defense ————————————————————————————— Carl Nelius, member Charles Becker, deputy Staff assistance for domestic geographic names provided by the U.S. Geological Survey Communications about domestic names should be addressed to: Donald J. -

There Is Freedom Catholic Foundation of Northeast Kansas | 2017-2018 Annual Report Dear Friends in Christ

1989 2019 Where the Spirit of the Lord is There is Freedom Catholic Foundation of Northeast Kansas | 2017-2018 Annual Report Dear Friends in Christ, The Holy Spirit empowers each of us with the freedom to walk in a new life in Christ. St. Paul writes, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.” Our Christian understanding of freedom is quite different than the prevailing concept in our secular culture. The notion of freedom popular in our society is the ability to do whatever we want as long as it does not harm anyone else. Where the Spirit The Christian understanding of authentic freedom is the ability to choose the “ good and the noble, no matter the external circumstances of our life. of the Lord is, Archbishop Joseph F. Naumann Each of us is blessed with the freedom to live a holy and fruitful life. “But there is freedom.” the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things, there is no law. 2 Corinthians 3:17 Those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires. Since we live by the Spirit, let us keep in step with the Spirit.” Galatians 5:22-25 The gifts of the Holy Spirit are manifested every day in the goodness of our faithful Catholic community in Northeast Kansas. I witness the fruits of the The Catholic Foundation of Holy Spirit in the wisdom of clergy and our parish and school leaders, in the Northeast Kansas is pleased to dedication of our teachers and employees, in the kindness and generosity of present this Annual Report to you, thousands of Catholic faithful. -

Catalyst Schools Davidson Cristo

2007 - 2009 Report William G. McGowan Charitable Fund High Jump Catalyst Schools Archbishop Carroll High School Access Living Solace Tree DeSales High School Project Exploration Women’s Davidson Resource Cristo Rey Academy Center NSTEP Perfect Wings Merit School King’s College of Neveda Umoja Marywood University Center for Inspired TeacConnected.hing Committed.Gardner Institute Zero to Three Project Sanctuary Young Women’s LeadershipCollaborative. Charter School Lourdesmont Camp Good Days and Special Times Bishop Ward Northeast Regional High School Cancer Institute Loyola Big Shoulders Night Ministry KIPP Note-Ables DePaul University KC Healthy Kids Sacred Heart Contents Letter from the President and Executive Director 2 William McGowan Connected. 3 William G. McGowan (1927-1992), a pioneering Initiatives in Education entrepreneur, was the motivating force behind the success of MCI and the inspiration for the William G. Committed. 11 McGowan Charitable Fund. A visionary leader, Mr. Healthcare & Medical Research Initiatives McGowan understood that opportunity unlocked the limitless power of innovation. During his 24 years as Collaborative. 15 the head—and very public face—of MCI, Mr. McGowan Community Initiatives for Those Most Vulnerable expanded the company from a struggling local radio service to a $9.5 billion telecommunications giant. Financial Statement 22 He was the driving force behind the toppling of the Ma Bell monopoly, and thanks to his dogged efforts and Grant Distribution 2007-2009 23 successful antitrust litigation, the previously regulated telecommunications industry was opened to competition Grant Making & Geographic Guidelines 24 and an entire industry was transformed. Vision To impact lives today, create sustainable change A man born of modest means, Mr. -

Library Director, Dean, Or University Librarian

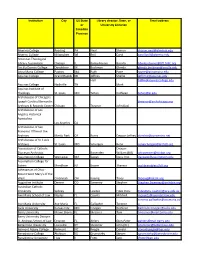

Institution City US State Library director, Dean, or Email address or University Librarian Canadian Province Alvernia College Reading PA Neal Sharon [email protected] Alverno College Milwaukee WI Brill Carol [email protected] American Theological Library Association Chicago IL Bailey-Hainer Brenda bbailey-hainer@ATLA RC.org Ancilla Domini College Donaldson IN Bockman Glenda [email protected] Anna Maria College Paxton MA Ruth Pyne [email protected] Aquinas College Grand Rapids MI Jeffries Shellie [email protected] Hall [email protected] Aquinas College Nashville TN Mark Aquinas Institute of Theology St. Louis MO Tehan Kathleen [email protected] Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin [email protected] Archives & Records Center Chicago IL Treanor John (Jac) Archdiocese of Los Angeles Historical Apostolate Los Angeles CA Archdiocese of San Francisco Office of the Archives Menlo Park CA Burns Deacon Jeffrey [email protected] Archdiocese of St. Louis Archives St. Louis MO Schergen Rena [email protected] Association of Catholic Deacon Diocesan Archivists Bissenden William (Bill) [email protected] Assumption College Worcester MA Sweet Doris Ann [email protected] Assumption College for Sisters Mendham NJ Bower Theresa [email protected] Athenaeum of Ohio - Mount Saint Mary's of the West Cincinnati OH Koenig Tracy [email protected] Augustine Institute Denver CO Sweeney Stephen [email protected] Australian Catholic University Sydney Lawton Fides Datu [email protected] Ave Maria School of Law Naples FL Counts Mitchell [email protected] [email protected] Ave Maria University Ave Maria FL Gallagher Terence u Avila University Kansas City MO Finegan Kathleen [email protected] Barry University Miami Shores FL Messner Tom [email protected] Barry University Dwayne O. -

Download This Dissertation

Copyright © 2013 Timothy J. Collins Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The journey has only begun, but what a blessing it has been for me and for my academic work to have the encouragement and support of many, many folks. It is not lost on me that, “it takes a village.” My family has made many sacrifices for me that allowed for the “guilt-free” focus of time and energy on this endeavor. So many colleagues at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory have coached, mentored, taught, and even occasionally prodded me throughout the doctoral program. I am particularly thankful for those closest to me at the Lab. Many times their extra effort in the workplace made things easier for me or ensured that I did not get lost in the forest. I am grateful for the educational experience offered to me by the faculty and staff of Benedictine University, who are so committed to the success of their learners. My extended family and friends, brother Knights of Columbus, BU cohort, colleagues from the armed forces, fellow aviators, “Holy Catholic College,” technical editor, neighbors, and many others who always seemed to be there at just the right time to say or do just the thing that was needed at the moment. I am thankful for the genuinely special people and deep thinkers on my dissertation committee who served this effort. -

1 2015-2016 Catalog 608 North 18Th Street Kansas City, KS 66102 P: (913)

2015-2016 Catalog 608 North 18 th Street Kansas City, KS 66102 P: (913) 621-6070 F: (913) 621-8719 www.donnelly.edu Donnelly College is a Catholic institution of higher education that seeks to continue the mission of Jesus Christ in our time by making the love of God tangible in our world. Specifically, the mission of Donnelly College is to provide education and community services with personal concern for the needs and abilities of each student, especially those who might not otherwise be served. 1 Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Mission ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Vision Statement ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Values ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Accreditation ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Directory of Catholic Libraries and Archives

Institution City US State or Website Canadian Province Alvernia College Reading PA http://www.alvernia.edu/library/ Alverno College Milwaukee WI https://www.alverno.edu/library/ American Theological https://www.atla.com/Pages/default.aspx Library Association Chicago IL Ancilla Domini College Donaldson IN https://www.ancilla.edu/current- students/ancilla-library/ Anna Maria College Paxton MA https://www.annamaria.edu/student- life/services/library Aquinas College Grand Rapids MI https://woodhous.aquinas.edu/ http://aquinascollege.libguides.com/homepa Aquinas College Nashville TN ge Aquinas Institute of https://www.ai.edu/Resources/Aquinas- Theology St. Louis MO Library Archdiocese of Chicago’s http://dnn7.archchicago.org/10156/Home.as Joseph Cardinal Bernardin px Archives & Records Center Chicago IL Archdiocese of Los https://laassubject.org/directory/profile/arch Angeles Historical diocese-los-angeles-archival-center Apostolate Los Angeles CA Archdiocese of San https://sfarchdiocese.org/chancellors-office Francisco Office of the Archives Menlo Park CA Archdiocese of St. Louis http://archstl.org/archives Archives St. Louis MO Association of Catholic http://diocesanarchivists.org/ Diocesan Archivists Assumption College Worcester MA https://www.assumption.edu/library Assumption College for http://acs350.org/library/ Sisters Mendham NJ Athenaeum of Ohio - http://library.athenaeum.edu/friendly.php?s Mount Saint Mary's of the =home West Cincinnati OH Augustine Institute Denver CO https://www.augustineinstitute.org/graduate -school/library/ Australian Catholic http://library.acu.edu.au/ University Sydney Ave Maria School of Law Naples FL https://www.avemarialaw.edu/library/ https://www.avemaria.edu/library/ Ave Maria University Ave Maria FL Avila University Kansas City MO https://www.avila.edu/academics/learning- commons Barry University Miami Shores FL https://www.barry.edu/library-services/ Barry University Dwayne https://www.barry.edu/law/future- O.