The Dark of the Covenant: Christian Imagery, Fundamentalism, and the Relationship Between Science and Religion in the Halo Video Game Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2015 Halo Championship Series (HCS) Season 1 Handbook

2014-2015 Halo Championship Series (HCS) Season 1 Handbook Version 1 Last updated: December 3, 2014 Table of Contents General Information…………………………………………………………………………………………..…....3 Definitions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……4 League Format…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……..4 Schedule…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….....5 How to Participate……………………………………………………………………………………………..…..…6 Online Tournament Format……………………………………………………………………………………...6 LAN Tournaments…………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 HCS Points……………..………………………………………………………………………………………………...10 Halo Championship Series Tournament Application……………………………………………….11 Team Structure and Player Trading……………………………………………………………………….…11 Official Tournament Map Pool & Game Types……………………………………………………...…13 Amendments & Additions………………………………………………………………………………………..15 2 General Information Description The Halo Championship Series (“HCS”) is the official Halo eSports league established by 343 Industries (“343”) to create the best environment and platform for competitive Halo gameplay. 343 is responsible for the coordination of partner management, direction, and government of the HCS. The official Halo game of the 2014-2015 year is Halo 2: Anniversary. Teams will compete in a mix of online and in-person LAN tournaments of varying tournament formats, prize pools, and “HCS Points” values. Turtle Entertainment / Electronic Sports League (“ESL”) is the official tournament organizer. Twitch Interactive, Inc. (“Twitch”) is the official HCS broadcast partner. Player Eligibility -

Halo: Combat Evolved Map Structure

Halo: Combat Evolved Map Structure Snowy Mouse Revision 2.1.2 This is a guide on the structure of the map files built for the game, Halo: Combat Evolved. Games discussed are as follows: • Xbox version - Halo: Combat Evolved on Xbox as released by Bungie • Retail PC version - Halo: Combat Evolved as released by Gearbox (and MacSoft for the Mac version) • Demo version - Demo / Trial versions of the PC version of the game • Custom Edition version - Halo Custom Edition on PC, an expansion to the PC version that enables the creation of custom maps • Anniversary version - Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary on MCC (also known as CEA) This document will not discuss the Xbox 360 version of Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary, nor will it discuss betas of the game due to the fact that these are numerous and also outdated. This document will also not discuss any community-created formats, as that would make it difficult to maintain and update this document every time someone made another formator updated an existing one. This document will also not go over the structure of tags, themselves, as this would require a lot of work as well as possibly hundreds of pages. If you actually need this information, you can find an up-to-date set of definitions in the Invader repository which canbefound on GitHub at https://github.com/SnowyMouse/invader/ All information here is provided freely, but this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (CC BY 3.0 US). For more information, you can read the license at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/ Copyright © 2021 by Snowy Mouse Halo: Combat Evolved Map Structure Snowy Mouse Contents 1 About the author 3 2 What is a map file? 4 2.1 Resource maps . -

Digital Commons@WOU Luminance

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2018 Luminance Ella Young Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Young, Ella, "Luminance" (2018). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 158. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/158 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Luminance a novel By Ella Young An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr Henry Hughes, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director June 2018 !1 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Plot Summary 3 Acknowledgements 50 Bibliography 51 Luminance Chapter One 4 Chapter Two 19 Artistic Reflection In the Beginning 35 Of Solar Flares and Shifting Poles 39 The Nitty Gritty 42 Fiction Becomes Reality 44 What the Future Holds 47 Only the first and second chapters have been included here. If you would like to read this work in its entirety, please visit Amazon.com to purchase the full novel. !2 Abstract For my thesis I decided to go the creative route and write a novel. There is a definite lack of LGBTQ+ genre fiction for young adults being written, and so I wanted to add to this slowly growing literary niche. -

Exploring the Experiences of Gamers Playing As Multiple First-Person Video Game Protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’S Single-Player Narrative

Exploring the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative Richard Alexander Meyers Bachelor of Arts Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Creative Practice Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords First-Person Shooter (FPS), Halo 3: ODST, Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), ludus, paidia, phenomenology, video games. i Abstract This thesis explores the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST, with a view to formulating an understanding of player experience for the benefit of video game theorists and industry developers. A significant number of contemporary console-based video games are coming to be characterised by multiple playable characters within a game’s narrative. The experience of playing as more than one video game character in a single narrative has been identified as an under-explored area in the academic literature to date. An empirical research study was conducted to explore the experiences of a small group of gamers playing through Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as a methodology particularly suited to exploring a new or unexplored area of research and one which provides a nuanced understanding of a small number of people experiencing a phenomenon such as, in this case, playing a video game. Data were gathered from three participants through experience journals and subsequently through two semi- structured interviews. The findings in relation to participants’ experiences of Halo 3: ODST’s narrative were able to be categorised into three interrelated narrative elements: visual imagery and world-building, sound and music, and character. -

Defense Research Agency Seeks to Create Supersoldiers, by Bruce

The following is mirrored from its source at: http://www.govexec.com/dailyfed/1103/111003nj1.htm Defense research agency seeks to create supersoldiers by Bruce Falconer National Journal / Government Executive Magazine 10 November 2003 Critics maligned the idea as "unbelievably stupid," "bizarre and morbid," and even "an incentive" for someone to actually "commit acts of terrorism." Once members of Congress and the media in July got wind of FutureMAP -- a plan by the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to create online futures markets where traders could speculate in the likelihood of terrorist attacks -- it was only a matter of hours before the project was sacrificed on the altar of political damage control. But even this, it seems, was too little, too late to appease an outraged Congress: House and Senate appropriations conferees working on the Defense budget have since voted to abolish large portions of the agency’s Terrorism Information Awareness program. The program -- of which FutureMAP was a small part -- was designed to mine private databases for information on terrorist suspects. DARPA, meanwhile, soldiers on with the kind of "blue-sky" thinking that is its charge. Indeed, the Pentagon agency that underwrote the development of some of the world’s most advanced technologies, such as the Internet, the Global Positioning System, and stealth aircraft, is now looking at technologies that will help U.S. troops soldier on, and on, and on. DARPA thinkers are saying that maybe humans themselves need an upgrade. "The human is becoming the weakest link," DARPA warned last year in an unclassified report. -

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

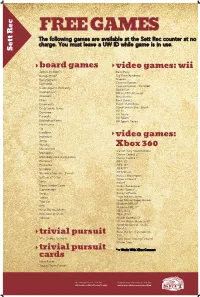

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Game Enforcer Is Just a Group of People Providing You with Information and Telling You About the Latest Games

magazine you will see the coolest ads and Letter from The the most legit info articles you can ever find. Some of the ads include Xbox 360 skins Editor allowing you to customize your precious baby. Another ad is that there is an amazing Ever since I decided to do a magazine I ad on Assassins Creed Brotherhood and an already had an idea in my head and that idea amazing ad on Clash Of Clans. There is is video games. I always loved video games articles on a strategy game called Sid Meiers it gives me something to do it entertains me Civilization 5. My reason for this magazine and it allows me to think and focus on that is to give you fans of this magazine a chance only. Nowadays the best games are the ones to learn more about video games than any online ad can tell you and also its to give you a chance to see the new games coming out or what is starting to be making. Game Enforcer is just a group of people providing you with information and telling you about the latest games. We have great ads that we think you will enjoy and we hope you enjoy them so much you buy them and have fun like so many before. A lot of the games we with the best graphics and action. Everyone likes video games so I thought it would be good to make a magazine on video games. Every person who enjoys video games I expect to buy it and that is my goal get the most sales and the best ratings than any other video game magazine. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Architecting & Launching the Halo 4 Services

Architecting & Launching the Halo 4 Services SRECON ‘15 Caitie McCaffrey! Distributed Systems Engineer @Caitie CaitieM.com • Halo Services Overview • Architectural Challenges • Orleans Basics • Tales From Production Presence Statistics Title Files Cheat Detection User Generated Content Halo:CE - 6.43 million Halo 2 - 8.49 million Halo 3 - 11.87 million Halo 3: ODST - 6.22 million Halo Reach - 9.52 million Day One $220 million in sales ! 1 million players online Week One $300 million in sales ! 4 million players online ! 31.4 million hours Overall 11.6 million players ! 1.5 billion games ! 270 million hours Architectural Challenges Load Patterns Load Patterns Azure Worker Roles Azure Table Azure Blob Azure Service Bus Always Available Low Latency & High Concurrency Stateless 3 Tier ! Architecture Latency Issues Add A Cache Concurrency " Issues Data Locality The Actor Model A framework & basis for reasoning about concurrency A Universal Modular Actor Formalism for Artificial Intelligence ! Carl Hewitt, Peter Bishop, Richard Steiger (1973) Send A Message Create a New Actor Change Internal State-full Services Orleans: Distributed Virtual Actors for Programmability and Scalability Philip A. Bernstein, Sergey Bykov, Alan Geller, Gabriel Kliot, Jorgen Thelin eXtreme Computing Group MSR “Orleans is a runtime and programming model for building distributed systems, based on the actor model” Virtual Actors “An Orleans actor always exists, virtually. It cannot be explicitly created or destroyed” Virtual Actors • Perpetual Existence • Automatic Instantiation • Location Transparency • Automatic Scale out Runtime • Messaging • Hosting • Execution Orleans Programming Model Reliability “Orleans manages all aspects of reliability automatically” TOO! TOO! TOO! Performance & Scalability “Orleans applications run at very high CPU Utilization. -

![Arxiv:1510.04980V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 22 Nov 2015 Eet Ta.21;D Aprne L 04.Hwvr Radio However, 2014)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3277/arxiv-1510-04980v2-astro-ph-co-22-nov-2015-eet-ta-21-d-aprne-l-04-hwvr-radio-however-2014-983277.webp)

Arxiv:1510.04980V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 22 Nov 2015 Eet Ta.21;D Aprne L 04.Hwvr Radio However, 2014)

DRAFT VERSION JULY 30, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 THE SCALING RELATIONS AND THE FUNDAMENTAL PLANE FOR RADIO HALOS AND RELICS OF GALAXY CLUSTERS 1,2 1 1 Z.S. YUAN ,J.L.HAN ,Z.L.WEN 1National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20A Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100012, China; [email protected] 2School of Physics, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China Draft version July 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Diffuse radio emission in galaxy clusters is known to be related to cluster mass and cluster dynamical state. We collect the observed fluxes of radio halos, relics, and mini-halos for a sample of galaxy clusters from the literature, and calculate their radio powers. We then obtain the values of cluster mass or mass proxies from previous observations, and also obtain the various dynamical parameters of these galaxy clusters from optical and X-ray data. The radio powers of relics, halos, and mini-halos are correlated with the cluster masses or mass proxies, as found by previous authors, with the correlations concerning giant radio halos being, in general, the strongest ones. We found that the inclusion of dynamical parameters as the third dimension can significantly reduce the data scatter for the scaling relations, especially for radio halos. We therefore conclude that the substructures in X-ray images of galaxy clusters and the irregular distributions of optical brightness of member galaxies can be used to quantitatively characterize the shock waves and turbulence in the intracluster medium responsible for re-accelerating particles to generate the observed diffuse radio emission. -

Score Pause Game Settings Fire Weapon Reload/Action Switch Weapo

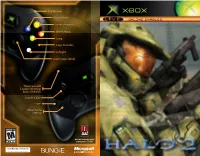

Fire Weapon Reload/Action ONLINE ENABLED Switch Weapons Melee Attack Jump Swap Grenades Flashlight Zoom Scope (Click) Throw Grenade E-brake (Warthog) Boost (Vehicles) Crouch (Click) Score Pause Game Settings Get the strategy guide primagames.com® ® 0904 Part No. X10-96235 SAFETY INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS About Photosensitive Seizures Secret Transmission ........................................................................................... 2 A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who Master Chief .......................................................................................................... 3 have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these Breakdown of Known Covenant Units ......................................................... 4 “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or Controller ............................................................................................................... 6 face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from Mjolnir Mark VI Battle Suit HUD ..................................................................... 8 falling down or striking -

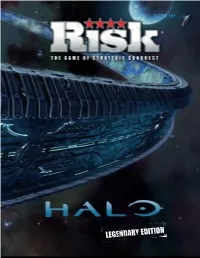

Halo Legendary Edition Overview of Components Cont

2-5 AGES 10+ PLAYERS RISK: HALO LEGENDARY EDITION OVERVIEW OF COMPONENTS CONT. “In a distant corner of the galaxy a new Halo ring, one of the ancient superweapons of the mysterious Forerunner civilization is found and the battle sparks anew: Brave Humanity, battling for survival and DICE discovery against the discipline and zealotry of the Covenant alliance of alien species who worship the long-absent Forerunners...and looming terrifying above both of these factions is the parasitic You use the dice when attacking and defending territories. Flood infection which threatens to corrupt all living creatures into mindless creatures of violence ( see ATTACKING, pg.10) and rage. Which faction will triumph in this legendary new front in the battle for the Halo universe? ATTACK DICE DEFENSE DICE That, players, is up to you...” MOBILE TELEPORTERS Pairs of Mobile Teleporters will be placed on the board onto different OVERVIEW OF COMPONENTS territories. These connect two previously separated territories. Forces can maneuver and attack normally via these Mobile Teleporters. (see USING Mobile Teleporters, pg. 8 for further explanation) WHAT’S INSIDE UNITS CONTENTS Every player will control a faction of one color. • 4 Battlefields • 2 UNSC Factions* • 22 Campaign cards Heroes • 2 Double-sided Game Boards • 2 COVENANT Factions** • 44 Faction cards Heroes possess elite skills in both attack • 10 Mobile Teleporters • 1 FLOOD Faction*** • 5 Bases and defense that can turn the tide of battle. • 5 Dice *UNSC - 1 spartan, 1 firebase, 36 marines, 18 tanks ( see ATTACKING, pg. 10 for further explanation) **Covenant - 1 aribiter, 1 command center, 36 grunts, 18 wraiths UNSC COVENANT FLOOD ***Flood - 1 thasher, 1 proto-gravemind, 36 infection forms and 18 carrier forms Not all components are used in every game mode.