How Warhol Foundation Head Joel Wachs Built a Pop Art Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Equestrian and Hiking Trails Plan*

Major Equestrian and Hiking Trails Plan* an Element of the Master Plan of the City of Los Angeles Prepared by the Department of City Planning and the Department of Recreation and Parks *Language transcribed verbatim from the plan December 1, 2009 by the Los Angeles Equine Advisory Committee. (All illustrations and maps omitted.) City of Los Angeles Major Equestrian and Hiking Trails Plan This plan consists of Statement of Policy, Features of the Plan, and Major Equestrian and Hiking Trails map Tom Bradley, mayor CITY COUNCIL Pat Russell, president Ernardi Bernardi Hal Bernson Marvin Braude David Cunningham Robert Farrell John Ferraro Howard Finn Joan Milke Flores Gilbert W. Lindsay Joy Picus Arthur K. Snyder Peggy Stevenson Joel Wachs Zev Yaroslavsky City Planning Commission Daniel P. Garcia, president Robert Abernethy William Luddy Suzette Neiman Board of Recreation and Parks Commissioners A.E. England, president Mrs. Harold C. Morton, vice-president Brad Pye, Jr. James Madrid Miss Patricia Delaney Master Plan Advisory Board Robert O. Ingman, public facilities committee chairman Department of Recreation and Parks William Frederickson, Jr., general manager Chester E. Hogan, executive officer John H. Ward, superintendent Alonzo Carmichael, planning officer Ted C. Heyl, assistant to planning officer Department of City Planning Calvin S. Hamilton, director of planning Kei Uyeda, deputy director of planning Glenn F. Blossom, city planning officer Advance Planning Division Arch D. Crouch, principal city planner Facilities Planning Section Maurice Z. Laham, senior city planner Howard A. Martin, city planner Ruth Haney, planning associate Brian Farris, planning assistant Franklin Eberhard, planning assistant Photographs by the Boy Scouts of America, the Los Angeles City Department of Recreation and Parks and the Los Angeles County Parks and Recreation Department. -

Public Matching Funds Summary 1993-2001

CITY ETHICS COMMISSION PUBLIC MATCHING FUNDS SUMMARY PRIMARY ELECTION GENERAL ELECTION MATCHING FUNDS MATCHING FUNDS ELECTION & CANDIDATE RECEIVED RECEIVED 1993 MAYORAL CANDIDATES Linda Griego $272,585.50 Nate Holden $135,154.00 Richard Katz $585,574.69 Nick Patsaouras $176,563.99 Stan Sanders $158,279.00 Joel Wachs $264,836.64 Mike Woo $667,000.00 $800,000.00 1993 CD-3 CANDIDATES Laura Chick $69,869.00 $92,789.34 Joy Picus $72,920.00 $73,475.77 Dennis Zine $24,101.00 1993 CD-5 CANDIDATES Laura Lake $45,930.00 1993 CD-7 CANDIDATES Richard Alarcon $27,708.00 $70,395.34 LeRoy Chase $22,056.00 Albert Dib $32,380.00 Lyle Hall $16,609.00 $52,549.34 Ray Magana $39,280.33 1993 CD-11 CANDIDATES Daniel Pritikin $29,538.00 1993 CD-13 CANDIDATES Jackie Goldberg $100,000.00 $111,358.34 Tom LaBonge $100,000.00 $106,313.34 Efren Mamaril $21,115.00 Tom Riley $48,673.00 Conrado Terrazas $45,272.50 Michael Weinstein $47,399.75 1993 CD-15 CANDIDATES Joan Milke-Flores $78,429.00 $82,999.26 Warren Furutani $100,000.00 Janice Hahn $54,328.00 Diane Middleton $66,440.00 Rudy Svorinich $51,492.90 $82,207.34 TOTAL: $3,353,535.30 $1,472,088.07 PRIMARY ELECTION GENERAL ELECTION MATCHING FUNDS MATCHING FUNDS ELECTION & CANDIDATE RECEIVED RECEIVED 1995 CD-5 CANDIDATES Jeff Brain $19,138.84 Mike Feuer $98,855.00 $92,170.70 Roberta Weintraub $100,000.00 1995 CD-10 CANDIDATES J. -

A Century of Fighting Traffic Congestion in Los Angeles 1920-2020

A CENTURY OF FIGHTING TRAFFIC CONGESTION IN LOS ANGELES 1920-2020 BY MARTIN WACHS, PETER SEBASTIAN CHESNEY, AND YU HONG HWANG A Century of Fighting Traffic Congestion in Los Angeles 1920-2020 By Martin Wachs, Peter Sebastian Chesney, and Yu Hong Hwang September 2020 Preface “Understanding why traffic congestion matters is … not a matter of documenting real, observable conditions, but rather one of revealing shared cultural understandings.” Asha Weinstein1 The UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy was founded in 2017 through a generous gift from Meyer and Renee Luskin. It is focused on bringing historical knowledge to bear on today’s policy deliberations. Meyer Luskin stated that “The best way to choose the path to the future is to know the roads that brought us to the present.” This study is quite literally about roads that brought us to the present. The Los Angeles region is considering alternative forms of pricing roads in order to address its chronic congestion. This is a brief history of a century of effort to cope with traffic congestion, a perennial policy challenge in this region. The authors, like the Luskins, believe that the current public debate and ongoing technical studies should be informed by an understanding of the past. We do not duplicate technical or factual information about the current situation that is available elsewhere and under scrutiny by others. We also do not delve deeply into particular historical events or past policies. We hope this overview will be useful to lay people and policy practitioners participating in the public dialog about dynamic road pricing that will take place over the coming several years. -

Joel Wachs Gay and Lesbian Records, 1983-1996 Coll2014.119

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8df6vc8 No online items Finding Aid to the Joel Wachs Gay and Lesbian Records, 1983-1996 Coll2014.119 Kyle Morgan Processing this collection has been funded by a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 (213) 821-2771 [email protected] Finding Aid to the Joel Wachs Gay Coll2014.119 1 and Lesbian Records, 1983-1996 Coll2014.119 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Title: Joel Wachs gay and lesbian records creator: Wachs, Joel Identifier/Call Number: Coll2014.119 Physical Description: 1 Linear Feet1 flat archive box Date (inclusive): 1983-1996 Abstract: Gay and lesbian-related legal records, correspondence, and awards of Los Angeles City Councilmember Joel Wachs, 1983-1996. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open to researchers. There are no access restrictions. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the ONE Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Preferred Citation [Box/folder #, or item name] Joel Wachs Gay and Lesbian Records, Coll2014-119, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California. Immediate Source of Acquisition Date and method of acquisition unknown. -

A Touch of Wilderness: Oral Histories on the Formation of the Santa

A Touch of Wilderness: The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area A TOUCH OF WILDERNESS Oral Histories on the Formation of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area by Leonard Pitt, Ph.D. Professor of History Emeritus California State University, Northridge Los Angeles, California April 2015 A Touch of Wilderness: The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area A Touch of Wilderness: The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Report Certification I certify that A Touch of Wilderness: Oral Histories on the Formation of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area has been reviewed against the criteria contained in 43 CFR 7.18(a)(1) and upon the recommendation of Phil Holmes, Cultural Anthropologist, and Gary Brown, Cultural Resource Program Manager, has been classified as Available. ____________________________________ David Szymanski, Superintendent Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area _April 23, 2015________________________ Date A Touch of Wilderness: The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area A Touch of Wilderness: The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area A TOUCH OF WILDERNESS Oral Histories on the Formation of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area by Leonard Pitt, Ph.D. Professor of History Emeritus California State University, Northridge Funded under Cooperative Agreement No. 1443 CA8540-94-003 between The Santa Monica Mountains and Seashore Foundation and The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, National Park Service, Pacific West Region -

Joel Wachs Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c82r3sdr No online items Joel Wachs Papers Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu © 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Joel Wachs Papers CSLA-29 1 Joel Wachs Papers Collection number: CSLA-29 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Clay Stalls Date Completed: 2006 Encoded by: Clay Stalls © 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Joel Wachs papers Dates: 1951-2002 Bulk Dates: 1969-2002 Collection number: CSLA-29 Creator: Wachs, Joel Collection Size: 116 archival document boxes, 1 records storage box, 4 oversize boxes, 4 flat files Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: This collection contains constituent correspondence, mayoral and city council campaign records, and some personal papers of Joel Wachs, Los Angeles city councilman from 1971 until 2001. The holdings are especially valuable for understanding the critical mayoral campaigns in Los Angeles in 1993 and 2001, as well as issues of concern to the constituents of his city council district. These materials are not official city records; the official records of his city council tenure are located in the Los Angeles City Archives (213-473-8449). To learn more about the contents of this collection and their organization, consult the following sections of this on-line guide. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. -

Own 51 Library, the New Festival ••••• 59 Going Out

• • , • • • • • • , NEWS Dancing Out. 72 Theory and Practice 10 Bar Guide 73 Notes From Home 12 Community Directory 75 News 14 Classifieds 79 Eye Spy 14 Personals 87 > Queer Planet.. 16 ARTS Rim Shots ; .20 , Film: Truth or Dare May:!r Rus man.ds at theBaIgirI. •• 52 DEPARTMEN:TS EXPOSED . ' - , .- Manica Dorenkamp watches a Outspoken .t~,':~.4'•world of m;srepresentation. ••• :54 'Letters , 5 ~ 1; .. BOOKS: Essex Hemphill Stonewall Riots 5 Michael S. Smith talks to the Blurt Out ~.. 6 poet/editor •................... 55 Sotomayor , .. 8 , BOOKS: Brother to Brother , - Jennifer Camper · 8 Jim Marks on the hotly awilited Stomping Out. ; 9 anthology ....••..•••...•...••. 56 " Insider Trading .•....... ",..:26 MUSIC: A Month at the Opera AIDS This Week :,.:28 Bruce-Michael Gelbert spends Milestones ~.~30 one. ~.••.•..•. e••••••••••••••• 57 Look Out.. :.44 SIT AND SPIN Gossi p Watch '::46 New York:SMark Cicero ..... 58 Gaydar ,: 47 LIP SERVICE Field Tripping •.......... : .. 50 Daddy Kane update, the Center Out on the Town 51 Library, the New Festival ••••• 59 Going Out. 67 POETRY:This Dark Apartment Tuning In 71 James Schuyler •••.•..•••••• 60 FEATURES Keep Your Cool , Michael Wakefield documents queer summer fantasies. ••••••••••••••••••••• 34 - , • Cove...·Photo: Michael Wakefield • C9ver model: Heather Murray " OutWeek (lSSN 1047-34421 is published weekly (51 iss~1 by OutWeek Publishing Corporation. 159 Wm 25th St. New Yor!r. N.Y. 10001 (2121337·1200. AppliCation to mall at $8COnd class postage rates is pending at New YorIc; N.Y. Subscription prices: $69.95 per year. ' Postmaster send change of address to OutWeek Magazine. 159 West 25 Street. 7th Floor. New YorlcNY 10001 The entil8 contents of OutWeek al8 copyright«l1!l91 by OutWeek Publishing Corporation. -

1990 Annual Report -2- Fire and Police Pension Systems CITY of Los ANGELES CALIFORNIA

ANNUAL REPORT < 1990 CITY OF LOS ANGELES DEPARTMENT OF PENSIONS FIRE AND POLICE PENSION SYSTEMS Department of Pensions, _ 360 East Second Street • Suite 600 • Los Angeles, California 90012 Annual Report 1990 Gary Mattingly General Manager James J. Mcfhiigan Allan Moore Assistant Manager Assistant Manager Siegfried O. Hillmer Dennis R. Sugino Assistant CityAttorney Chief Investment Officer Actuary Auditor Custodian Bank The Wyatt Company Deloitte & Touche Bankers Trust Company Table of Contents Membership Active Membership, ,.,, , .. , , . 5 Retired Membership ,, ., , , . , .... 7 Types of Pensions o S er'V'.l,ce.n..-enswns. , , , , ¥l,A,"' Disability Pensions . .,, ' .,. .. .. 12 Actuarial Report , . , . , , .. ,, 16 Investments , , ,, , 20 Auditor's Report. , , , ,24 Budget , . , , 29 Legal Summary , ,,. ,., 31 Description of Pension Benefits 38 Milestones , ., .. 42 MAYOR Tom Bradley City Attorney Controller James Kenneth Hahn Rick Tuttle CITY COUNCIL John Ferraro, President Marvin Braude, President Pro Tempore Gloria Molina Joel Wachs JoyPicus First District Second District Third District John Ferraro ZevYaroslavsky Ruth Galanter Fourth District Fifth District Sixth District Ernani Bernardi Robert C. Farrell Gilbert W.Lindsay Seventh District Eighth District Ninth District Nate Holden Marvin Braude Hal Bernson Tenth District Eleventh District Twelfth District Michael Woo Richard Alatorre Joan Milke Flores Thirteenth District Fourteenth District Fifteenth District BOARD OF PENSION COMMISSIONERS Dellene Arthur, President Kenneth E. Staggs Kenyon S. Chan VicePresident Commissioner Sam Diannitto Paul C. Hudson Commissioner Commissioner Dave Velasquez Leland Wong Commissioner Commissioner Dept. of Pensions 1990 Annual Report -2- Fire and Police Pension Systems CITY OF Los ANGELES CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF ALLAN E.MOORE PENSIONS ASSISTANT GENERAL MANAGER-FISCAL 360 EAST SECOND STREET JAMES J. McGUIGAN SUITE 600 ASSISTANT GENERAL MANAGER-BENEFITS LOS ANGELES. -

Los Angeles City Council File No. 85-0869 S2 Los Angeles City Council File No

Pages 3 – 89: Los Angeles City Council File No. 85-0869 S1 Pages 3 – 7: Public Health, Human Resources, and Senior Citizens Committee Report to Council of the City of Los Angeles (8/13/85) Pages 91 – 105: Los Angeles City Council File No. 85-0869 S2 Los Angeles City Council File No. 85-0869 S2 File No. 85-0869 Sl TO THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES -1- Your PUBLIC HEALTH, HUMAN RESOURCES, AND SENIOR CITIZENS Committee reports as follows: RECOMMENDATION That the proposed ordinance providing for civil penalties against those who discriminate against persons with AIDS or AIDS related conditions in the fields of housing, employment, and/or public services and accommodations BE PLACED UPON ITS PASSAGE. SUMMARY Your Public Health, Human Resources and Senior Citizens Committee began a series of hearings on the subject of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) medical condition pursuant to a Motion (Yaroslavsky-Bernardi-Stevenson) requesting recommendations on ways that the City can involve itself in fighting the epidemic and supporting its citizens who have been touched by the disease. After the first of these hearings, a second Motion (Wachs-Snyder) requesting an ordinance prohibiting discrimination against persons with AIDS was referred to your Committee. At hearings conducted on June 19, July 23, and August 13, 1985, your Committee learned that the first cases involving AIDS were reported in Los Angeles in 1981. Since that time over 900 cases of AIDS have been reported in Los Angeles County. The number of reported cases is growing geometrically, currently doubling every fourteen months. -

Laws, Policies, Panel Says

Cos ~-\ngrlc.6 OTimc.6 Friday. M~y 20, 1988 Changes in Family ~ife Requir~ ~ew Laws, Policies, Panel Says By KEVIN RODERICK, Times Staff Writer Family life in Los Angeles has changed so much,Plat partner status and announced Wednesday that he and city officials can help by helping city workers with many laws and policies should be changed to acknowl would seek a change in the personnel practices that child care and giving preference on contracts to firms edge the new order, a task force of citizens recom govern Los'Angeles city employees. that provide child care for their own employees. He said employees who are not married but who mended Thursday to Mayor Tom Bradley and the City Developers should also be allowed to build bigger Council. have established a household with someone should be For instance, with so many people in Los Angeles given the same family sick and bereavement leave as buildings as an enticeme)lt to provide child-care not married, the City Council and other arms of . married couples. Woo said he planned to introduce the facilities, the report said. government should give some legal "domestic part measure in the City Council today. In a city with a population estimated at 3.5 million, ner" status to unmarried couples and forbid consumer the rep~rt said, about 500,000' have some disability and discounts that aim only at married people,· the Task Non-TractltloDal LiviD' ArrangemeDts Force on Family Diversity report said. The report seeks to make the point that most people another 200,000 are gay men or lesbians. -

Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project

Los Angeles Unified School District Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Los Angeles Unified School District Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Written and Edited by Bob and Sandy Collins All publication, duplication and distribution rights are donated to the Los Angeles Unified School District by the authors First Edition August 2016 Published in the United States i Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Founding Committee and Contributors Sincere appreciation is extended to Ray Cortines, former LAUSD Superintendent of Schools, Michelle King, LAUSD Superintendent, and Nicole Elam, Chief of Staff for their ongoing support of this project. Appreciation is extended to the following members of the Founding Committee of the Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project for their expertise, insight and support. Jacob Aguilar, Roosevelt High School, Alumni Association Bob Collins, Chief Instructional Officer, Secondary, LAUSD (Retired) Sandy Collins, Principal, Columbus Middle School (Retired) Art Duardo, Principal, El Sereno Middle School (Retired) Nicole Elam, Chief of Staff Grant Francis, Venice High School (Retired) Shannon Haber, Director of Communication and Media Relations, LAUSD Bud Jacobs, Director, LAUSD High Schools and Principal, Venice High School (Retired) Michelle King, Superintendent Joyce Kleifeld, Los Angeles High School, Alumni Association, Harrison Trust Cynthia Lim, LAUSD, Director of Assessment Robin Lithgow, Theater Arts Advisor, LAUSD (Retired) Ellen Morgan, Public Information Officer Kenn Phillips, Business Community Carl J. Piper, LAUSD Legal Department Rory Pullens, Executive Director, LAUSD Arts Education Branch Belinda Stith, LAUSD Legal Department Tony White, Visual and Performing Arts Coordinator, LAUSD Beyond the Bell Branch Appreciation is also extended to the following schools, principals, assistant principals, staffs and alumni organizations for their support and contributions to this project. -

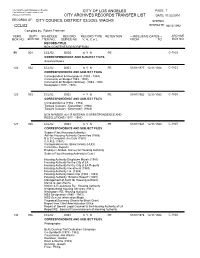

CD 02 Joel Wachs

City Clerk/Records Management Division PAGE: 1 City Archives Records Transfer List CITY OF LOS ANGELES (Revised 03/29/2000) CITY ARCHIVES RECORDS TRANSFER LIST DATE: 01/22/2004 RECORDS OF: CITY COUNCIL DISTRICT 02/JOEL WACHS SHIPNO: CCL/02 SHIPDATE: 06/12/1992 Compiled by: Robert Freeman VERS. DEPT. SCHEDULE RECORD RECORD TYPE RETENTION ---INCLUSIVE-DATES--- ARCHIVE BOX NO.BOX NO. ITEM NO. SERIES NO. V, H, C or L FROM TO BOX NO. RECORD-TITLE BOX CONTENTS/DESCRIPTION 99 001 CCL/02 O003 N Y NPE C-1822 CORRESPONDENCE AND SUBJECT FILES Assorted Books 124 002 CCL/02 O003 N Y N PE 01/01/1977 12/31/1984 C-1823 CORRESPONDENCE AND SUBJECT FILES Correspondent & Newspapers (1983 - 1984) Comments on Budget 1983 - 1984) Comments on Budget (continue) (1983 - 1984 Newspaper (1977 - 1983) 125 003 CCL/02 O003 N Y N PE 01/01/1982 12/31/1983 C-1824 CORRESPONDENCE AND SUBJECT FILES Correspondence (1982 - 1983) Tissues (January - December) (1982) Tissues (January - December) (1983) BOX NUMBER 004 IS MISSING (CORRESPONDENCE AND RESOLUTIONS (1977 - 1981) 127 005 CCL/02 O003 N Y N PE 01/01/1981 12/31/1983 C-1825 CORRESPONDENCE AND SUBJECT FILES Subject Files (Housing Authority) Ad Hoc Housing Authority Committee (1983) B & S Complaint-Jim Cato (1981) C.A.R.E. (1981) Corrspondence Re. Block Grants (HUD) Committee Reports Employee Attitude Survey for Housing Authority Subject Files (Housing Authority) (Cont.) Housing Authority Employee Morale (1983) Housing Authority for the City of LA Housing Authority for the City of LA Reports Housing Authority Investment (1983) Housing Authority Lat.