Proposed West Midlands Low Emissions Vehicle Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Marches Growth Hub Steering Group 19 March 2020

Minutes of Marches Growth Hub Steering Group 19 March 2020 Present Paul Hinkins PH Marches Growth Hub Chair, Marches LEP Board Deputy Chair Oliver Hindle OH Marches Are Lead – Cities and Local Growth Unit, BEIS Frank Myers MBE FM LEP Board Member, Chair of Herefordshire Business Board – Director MCP Systems Consultants Ltd Colin Preece CP Marches Skills Provider Network Executive Officer Amy Bould AB Marches LEP PR & Marketing, Director Be Bold Media Ltd Maisy Owen MO Chamber Member - Chair of Members Committee, Director MO Management Consultancy Ltd Beth Heath BH Shropshire Business Board Representative, Director Shropshire Festivals, Director Shropshire Think Tank Hollie Whittles HW Federation of Small Businesses - Area Lead Shropshire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire and Director Fragglesworks Richard Nicklin PB University of Wolverhampton, External Relations Deputy Director – Business Engagement Steve Havins SH D epartment for International Trade, Head of Business Development & Partnerships Nick Webster NW Herefordshire Council - Economic Development Manager Delia Yapp DY Shropshire Council, Key Accounts and Investment Manager Yasmin Sulaman YS Marches LEP Business Support Project Officer Kathryn Jones LP Marches LEP Partnership Manager Apologies: Matt Potts - Shropshire Council Business Growth and Inward Investment Manager Katharine Clough – University of Wolverhampton, Director – External Relations Colin Thaw - Marches Skills Provider Network Chair, Director SBC Training Not Present: Kathy Mulholland - Telford & Wrekin Council - Inward Investment & Business Support Service Delivery Manager ITEM ACTION 1. Welcome and Introductions PH welcomed Steering Group (SG) Members to the telephone call meeting and highlighted new members to the group. Roundtable introductions were followed by YS confirming apologies. 2. Declarations of Member Interest No declarations of interest were noted in relation to any agenda item. -

Acceptance of Tenders for Local Bus Services

Shropshire County Council - Passenger Transport Group Transport Act 1985 Section 89 - Acceptance of Tenders for Local Bus Services Closing Date : 23 August 1999 Introduction Date : 1 November 1999 TENDER CONTRACT ROUTE DAYS OF NO. OF SUCCESSFUL COST OF HIGHEST LOWEST NUMBER NUMBER OPERATION TENDERS TENDERER SUCCESSFUL TENDER TENDER TENDER £ per week £ per week £ per week Z249 SOPT115 702 Ludlow Circular Mondays to 3 R & B Travel 810.00 MC 1660.00 MC 414.10 MC (A) Saturdays 918.00 MS 450.00 MS Notes (A) - Option 2 not taken up MS - Minimum Subsidy MC - Minimum Cost H:\Imp_Div\ITU_TranServ\Shared\School & Public Transport\Contracts\Contract Documents\LBS Tender Results\LBS Tender Results 1999 to 31 March 2009.doc Shropshire County Council - Passenger Transport Group Transport Act 1985 Section 89 - Acceptance of Tenders for Local Bus Services Closing Date : 1 September 1999 Introduction Date : 1 November 1999 TENDER CONTRACT ROUTE DAYS OF NO. OF SUCCESSFUL COST OF HIGHEST LOWEST NUMBER NUMBER OPERATION TENDERS TENDERER SUCCESSFUL TENDER TENDER TENDER £ per week £ per week £ per week Z251 COPT201 Shrewsbury Park & Ride Mondays to 3 Arriva Midland 3,852.00 MC 9984.36 MC 3,852.00 MC Meole Brace - Town Centre Saturdays North Notes MS - Minimum Subsidy MC - Minimum Cost H:\Imp_Div\ITU_TranServ\Shared\School & Public Transport\Contracts\Contract Documents\LBS Tender Results\LBS Tender Results 1999 to 31 March 2009.doc Shropshire County Council - Passenger Transport Group Transport Act 1985 Section 89 - Acceptance of Tenders for Local Bus Services Closing Date : 31 October 2000 Introduction Date : 18 November 2000 TENDER CONTRACT ROUTE DAYS OF NO. -

Flock Book 111 (2011)

THE SHROPSHIRE SHEEP BREEDERS’ ASSOCIATION AND FLOCK BOOK SOCIETY FLOCK BOOK Volume 111 2011 Ram Registrations 1785 ‐ 1899 Ewe Registrations F09752 – F10847 Secretary: Mr Simon Mackay 146 Chandlers Way Sutton Manor St Helens WA9 4TG Tel/FAX: 00 44 (0)1744 811124 E‐Mail: shropshire_sheep @ hotmail.com Web Site: www.shropshire‐sheep.co.uk REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER 1115599 The Shropshire Sheep Breeders’ Association and Flock Book Society Flock Book Volume 111 2011 Ram Registrations 1785 ‐ 1899 Including Rams Exported: 1495,1751,1754,1788,1819,1823,1825,1827,1828,1829,1830,1831,1833,1838 Ewe Registrations F09752 – F10847 Produced by Mrs A Schofield Brookfield Farm Sproston Green Holmes Chapel Cheshire CW4 7LN Tel/Fax 01477 533256 -2- Contents Page Index of Advertisers………………………………………….……. .….4 An Introduction to Shropshire Sheep…………………………… …..5 Shropshire Facts and Figures…………………………………….. …..7 Official Breed Description…………………………….………….. …..8 Objectives of the Society……………………………...…………... …..9 List of Officers, Council and Committee Members……………. ..11 Past Presidents…………………………………..………………… …12 Secretaryʹs Report to the Annual General Meeting 2011……… …13 President’s Report to the Annual General Meeting 2011……… …17 Sales Officer’s Report to the Annual General Meeting 2011….. …21 Showing Shropshire Sheep………………………………...…….. …26 Society’s Annual Show Points Trophy Winners …27 Show Trophies and Winners……………………………………... …28 Regulations and Conditions of Entry to Flock Book…………... …30 Regulations on the Export of Sheep……………………………... …33 SSBA Official Ear Marking System………………...………......... …41 Ram Registrations for 2011…………………………....……......... …43 Ewe Registrations for 2011…………………………....……......... …65 Rams Exported 2011………………………………..……………... ..171 Ewes Exported 2011………………………………..……………… ..175 Annual Flock Returns for 2011…………………………………... ..191 New Flocks Introduced to the Society in 2011…….……………. ..213 Show Results 2011………………………………………..……….. ..218 List of Members, with Prefix Letters and Addresses………… ..233 Regulations on the Upgrading of Unregistered Ewes…..……. -

Local Bus Services Funded by Worcestershire County Council Consultation Response Analysis Other Indicators

Local Bus Services Funded by Worcestershire County Council Consultation Response Analysis Other Indicators Consultation Responses Responses Consult- Consult- Petitions Nominal Weighted Concess- School Rural Evening, Responses as a Ranking ation ation Received Subsidy per Perform- ionary Journeys Service: Sunday, Percentage of Response Response Number of passenger ance Passengers Alternativ Total Pass- Passenger Score: Score Signatures Indicator Percentage es enger Journeys Unweighted Ranking: Available Service Journeys Unweighted Operator Number Description Days / Notes pa Diamond 4 / 4A Fairfield -> Kidderminster via Puxton Drive, Franche, Ferndale Monday to Saturday 29,784 88 0.3% 59 2.00 38 £0.51 75 45% Bus Diamond Monday to Saturday, 5 Kidderminster -> Puxton Drive -> Kidderminster 21,216 91 0.4% 52 2.52 3 £0.49 75 45% Bus Afternoon journeys Central 007 The Oakhalls - Bromsgrove - Halesowen via Catshill, Romsley Monday to Saturday 47,218 238 0.5% 47 2.00 38 £1.34 70 51% Y Y Buses Whittles 7 Kidderminster - Fairfield via Greenhill, Sion Hill Monday to Saturday 55,145 99 0.2% 70 2.38 8 £0.42 75 37% WCC 7A Kidderminster - Offmore Road Monday to Friday 1,347 23 1.7% 17 2.25 19 £1.41 64 96% Whittles 15, S15 Kidderminster - Stourport - Bewdley via Wilden Monday to Saturday 32,785 221 0.7% 40 2.00 38 £2.16 69 49% Y WCC 17 Droitwich - Cockshute Hill (Circular) Monday to Saturday 11,000 32 0.3% 62 2.50 4 £0.39 63 62% WCC 18 Droitwich - New Chawson (Chalverton Court) Monday to Saturday 9,500 61 0.6% 42 2.25 19 £0.63 63 62% WCC 19A / 19C Droitwich -

Public Buses for Pupils and Students

Shropshire Council Covid-19 - Public Buses for Pupils and Students In 2020 the Government introduced on-bus social distancing on public transport buses as part of measures to deal with Covid-19, which in turn significantly reduced the carrying capacity of these buses. In September 2020 Shropshire Council, in partnership with the Department of Education and local transport operators introduced additional buses (‘Shadow’ buses) to carry pupils and students to school/college where their usual public bus service didn’t have enough capacity. During the 2020/21 academic year the ‘Shadow’ buses provided enough extra capacity to ensure that all pupils and students could travel as normal. In summer 2021 the Government began relaxing on-bus social distancing rules as the Covid-19 emergency eased, thus increasing bus capacity. Planning for the removal of the ‘Shadow’ buses was then begun, focused on where the extra capacity was no longer needed or to coincide with the end of the school summer term 2021. Details of the ‘Shadow’ buses provided are shown in Table 1 below, along with the date of their last day of operation. Some other public bus services were changed into ‘Schools Only’ services in 2020 and their operators will consider whether or not to open these up to the general public from September 2021. From September 2021 it is not planned to provide any ‘Shadow’ buses or additional capacity, but Shropshire Council and bus operators will monitor passenger capacity on public buses and where needs be address any capacity issues. Any remaining tightness in capacity may be further eased by the Government’s on-going Covid-19 social distancing strategy. -

User Company Register Number Registered Office Category of Use Date Signed 3R Enenrgy Solution Limited SC354680 , the Mechanics

User Company Register Number Registered Office Category of Use Date Signed 3R Enenrgy Solution Limited SC354680 , The Mechanics Workshop, New Lanark, Lanark, Lanarkshire ML-11 9DB Directly Connected Power Station Aberarder Wind Farm 00398487 Beaufort Court,Egg Farm Lane,Kings Langley,Hertfordshire,WD4 8LR Directly Connected Power Station Aberdeen Offshore Wind Farm Limited SC278869 Johnstone House, 52-54 Rose Street, Aberdeen, AB10 1HA Directly Connected Power Station Abergelli Power Limited 08190497 33 Cavendish Square, London, WIG OPW Directly Connected Power Station Abernedd Power Company Limited 06383166 6th Floor, Riverside Building, County Hall, London SE1 7BF Directly Connected Power Station ABO WIND UK LIMITED SC314110 1 Houstoun Interchange Business Park, Livingston, West Lothian, EH54 5DW Directly Connected Power Station A'Chruach Wind Farm Limited 06572505 First Floor , 500 Pavillion Drive , Northampton Business Park ,Northampton ,NN4 7YL Directly Connected Power Station Addito Supply Limited 8053202 1 America Square, Crosswall, London, EC3N 2SG Interconnector User AES Energy Limited 3896738 37 Kew Foot Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 2SS Supplier Aikengall Community Wind Company Limited SC313596 Edinburgh Quay, 133 Fountain Bridge, Edinburgh, EH3 9AG Embedded Exemptable Large Power Station Airies Wind Farm Limited SC407954 Suite F3 Clyde View, Riverside Business Park, 22 Pottery Street, Greenock, Inverclyde, PA15 2UZ Directly Connected Power Station Airtricity Developments (Scotland) Limited SC212524 Inveralmond House, 200 Dunkfield -

2015 National Fares Survey

TAS National Fares Survey 2015 30210 February 17 Final Quality Assurance Document Management Document Title TAS National Fares Survey 2015 Name of File 30210 REP TAS National Fares Survey 2015.docx Last Revision Saved On 06/02/2017 12:10:00 Version Final Draft Prepared by AS/MM/RT Checked by SW Approved by AG Issue Date Jan 2017 Copyright The contents of this document are © copyright The TAS Partnership Limited, with the exceptions set out below. Reproduction in any form, in part or in whole, is expressly forbidden without the written consent of a Director of The TAS Partnership Limited. Cartography derived from Ordnance Survey mapping is reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of HMSO under licence number WL6576 and is © Crown Copyright – all rights reserved. Other Crown Copyright material, including census data and mapping, policy guidance and official reports, is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland under licence number C02W0002869. The TAS Partnership Limited retains all right, title and interest, including copyright, in or to any of its trademarks, methodologies, products, analyses, software and know-how including or arising out of this document, or used in connection with the preparation of this document. No licence under any copyright is hereby granted or implied. Freedom of Information Act 2000 The TAS Partnership Limited regards the daily and hourly rates that are charged to clients and the terms of engagement under which any projects are undertaken, as trade secrets and therefore exempt from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act. -

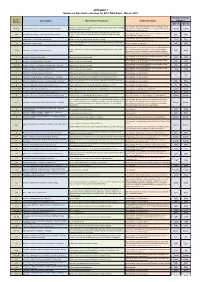

APPENDIX 1 Update on Bus Service Review for ECC O&S Panel

APPENDIX 1 Update on Bus Service Review for ECC O&S Panel - March 2015 Weekly Passenger Service Description Bus Review Proposals Additional Notes Numbers Number Oct-13 Oct-14 As per proposal. Route then amended in Jan 15 to incorporate part of Minimum of hourly service for all areas to be retained through most of the day. Timetables 4 / 4A / 5 Fairfield -> Kidderminster via Puxton Drive, Franche, Ferndale route affected by withdrawal of Whittles services. Some initial operating revised. Some new links provided. Comm Comm problems with new route in January. Simliar replacement service between Bromsgrove and Halesowen via Catshill and As per proposal. Service between Bromsgrove and Halesowen provided 007 The Oakalls - Bromsgrove - Halesowen via Catshill, Romsley Romsley. A service between Oakalls and Bromsgrove will be provided by rerouting commercailly and extended to Worcester. N/A N/A another service. As per proposal. Route then amended in Jan 15 to incorporate part of 7 Kidderminster - Fairfield via Greenhill, Sion Hill Similar level of service to be provided, with some retimings route affected withdrawal of Whittles services 728 719 Service not being replaced but close to other bus routes and Community Transport also 7A Kidderminster - Offmore Road Commercial replacement provided. provides an alternative. N/A N/A As per propsal, then revised and extended to serve Lickhill and Burlish in Similar replacement service but incorporating additional Stourport Estates and include Jan 15 following withdrawal of Whittles services. From Dec 2014 15, S15 Kidderminster - Stourport - Bewdley via Wilden Tesco. reduced level of service to Bewdley following withdrawal of Whittles 507 683 services. -

The Works Brass Band – a Historical Directory of the Industrial and Corporate Patronage and Sponsorship of Brass Bands

The works brass band – a historical directory of the industrial and corporate patronage and sponsorship of brass bands Gavin Holman, January 2020 Preston Corporation Tramways Band, c. 1910 From the earliest days of brass bands in the British Isles, they have been supported at various times and to differing extents by businesses and their owners. In some cases this support has been purely philanthropic, but there was usually a quid pro quo involved where the sponsor received benefits – e.g. advertising, income from band engagements, entertainment for business events, a “worthwhile” pastime for their employees, corporate public relations and brand awareness - who would have heard of John Foster’s Mills outside of the Bradford area if it wasn’t for the Black Dyke Band? One major sponsor and supporter of brass bands, particularly in the second half of the 19th century, was the British Army, through the Volunteer movement, with upwards of 500 bands being associated with the Volunteers at some time – a more accurate estimate of these numbers awaits some further analysis. However, I exclude these bands from this paper, to concentrate on the commercial bodies that supported brass bands. I am also excluding social, civic, religious, educational and political organisations’ sponsorship or support. In some cases it is difficult to determine whether a band, composed of workers from a particular company or industry was supported by the business or not. The “workmen’s band” was often a separate entity, supported by a local trade union or other organisation. For the purposes of this review I will be including them unless there is specific reference to a trade union or other social organisation. -

Contaminated Land Strategy

REPORT CONTAMINATED LAND INSPECTION STRATEGY Carried out for : Warwick District Council June 2001 Report No : 271040 CONTAMINATED LAND INSPECTION STRATEGY Carried out for : Warwick District Council CL Associates, Station House, Old Warwick Road, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV31 3NR, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1926 431007 Fax: +44 (0) 1926 431008 Email: [email protected] 2 WARWICK DISTRICT COUNCIL CONTAMINATED LAND INSPECTION STRATEGY SUMMARY Regulations under Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 require Warwick District Council to produce a strategy to identify, inspect and remediate contaminated land within its area. The strategy covers all land within the district including that owned, previously owned or occupied by the Council. The strategy explains how the Council will take a rational, systematic and efficient approach to inspection; having regard to information and comments from statutory consultees (such as the Environment Agency) and other interested parties. Apart from the need to comply with the legislation the Council’s priorities in dealing with contaminated land are : • To protect human health • To protect controlled waters • To protect designated ecosystems • To prevent damage to property • To encourage re-use of brownfield land • To encourage voluntary remediation The Council's power to act applies only to "contaminated land" as defined by statute and may not therefore apply to every site which the public or even the Council may otherwise consider to be contaminated. The principle employed in the regulations is that land must be 'suitable for use'. This means that each site will have to be assessed separately to see whether a significant pollutant linkage is present. -

The Buzzard Shropshire Ornithological Society’S Quarterly Magazine

The Buzzard Shropshire Ornithological Society’s Quarterly Magazine No 256 Summer 2019 Society Officers and Officials President Peter Deans Vice Presidents Brian Andrews, Hugh Blofield, Chris Whittles Chairman and John Arnfield 01694 724170 Website [email protected] Honorary Helen J Griffiths, 104 Noel Hill Road, Cross Houses, Secretary Shrewsbury SY5 6LD 01743 761507 [email protected] Treasurer Jean Rickard, 17 Ebnal Road, Shrewsbury SY2 6PW 01743 367576 [email protected] Membership Annie Andrews, 6 Sytche Close, Much Wenlock TF13 6JJ 01952 727531 [email protected] Management Society Officers, and Graham Walker, Annie Andrews, Board Jim Almond, Sue Brealey, Tim Devanney Conservation: Graham Walker, 32 Sutton Grove, Shrewsbury SY2 6DN Chair 01743 351686 [email protected] Conservation John Tucker, Allan Dawes, Geoff Holmes, Simon Twigger, Sub-committee Leo Smith, Helen J Griffiths, Linda Munday, Jon Groom, Ian Grant, Gerry Thomas Development/ Sue Brealey, 6 Nobold, Baschurch, Shrewsbury SY42EA Publicity and 01939 262450 Field Trips [email protected] [email protected] Indoor Steve Dawes Programme [email protected] Trip Leaders See the annual programme County Bird Ian Grant 07590 422568 Recorder [email protected] Buzzard Editor Tim Devanney [email protected] Social Media Yvonne Chadwick [email protected] Bird Notes Jim Almond [email protected] Images and (Greenland White-fronted Goose at Attingham) Cover Image 2 Table of Contents Society Officers and Officials 2 Table of Contents 3 Welcome to New Members 4 From the Chair 4 SHROPSHIRE ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY Chair’s Report 2018/19 7 A study of the plastic ingestion and associated diet of great skua (Stercorarius skua) breeding on Fair Isle Shetland, through the dissection of pellets. -

Covid-19 - Public Buses for Pupils and Students

Shropshire Council Passenger Transport Group Covid-19 - Public Buses for Pupils and Students from 8th March 2021 Introduction Many Shropshire school pupils and students use public (LBS) buses to get to school/college, but because of Covid-19 seating regulations bus loading capacities are below 50%. When schools/colleges returned from the winter Lockdown in March 2021 many public buses still didn’t have enough capacity. Extra buses So, Government continue to ask local authorities to liaise with their schools and operators and arrange for additional peak time buses (or coaches) to be provided for school children and students in cases where there isn’t enough capacity. Where this was most likely, the Council has arranged via tender for extra temporary school/college only ‘Shadow’ buses to directly follow the main public bus with a ‘Schools Service’ sign and a service number displayed at the front of the bus, in order to provide extra capacity (please see list in Table 1. below). All school children and students should travel on these extra peak time buses, which were originally provided wef 2/9/20 in term time, but which were suspended in the Covid Lockdown between 6/1/21 and 7/3/21, and then reactivated on 8/3/21. Adult fare paying passengers should continue to use the main existing public buses. Principles Governing Extra Bus Deployment The provision of extra capacity by the Council on the public bus network for Shropshire residents is based on providing extra ‘shadow’ buses for inter urban and rural services only, where pupil/student numbers are over 10 on peak journeys.