Grasslands in the South?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mesowear Analysis of the Tapirus Polkensis Population from the Gray Fossil Site, Tennessee, USA

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Mesowear Analysis of the Tapirus polkensis population from the Gray Fossil Site, Tennessee, USA Julia A. Schap and Joshua X. Samuels ABSTRACT Various methods exist for measuring and analyzing dental wear patterns in mam- mals, and these patterns have been extensively studied in ungulates. Mesowear has proven useful as a method to compare large numbers of individuals, particularly fossil individuals, observe trends through time or between groups, and estimate paleoenvi- ronmental conditions. Levels of attrition (tooth-on-tooth wear) and abrasion (tooth-on- food wear) can be readily compared by observing the shape of the cusp and relative crown height of the tooth. This study uses a modified method of mesowear analysis, examining actual cusp angles of the population of Tapirus polkensis from the Gray Fos- sil Site, a densely canopied, hickory and oak dominated forest located in Gray, Tennes- see. Crown height and cusp angle were measured for 38 specimens arranged into eruption series from young juveniles to old adults. Results found a strong correlation between eruption series and cusp angle with a steady increase in mean angle as the individuals increase in age. A strong correlation between cusp angle and crown height was also found. Overall, the population showed relatively low wear rates, as would be expected of a forest-dwelling browser. As a mesowear analysis across all age groups for a population has not been conducted before, this study could be useful for measur- ing relative wear rates at different life stages and could be applied across other com- munities. Julia A. -

Nature 166(4219): 423

(1950). "PROF. L. Breitfuss." Nature 166(4219): 423. (1968). "New species in the tropics." Nature 220(5167): 536. (1968). "Weeds. Talking about control." Nature 220(5172): 1074-5. (1970). "Polar research: prescription for a program." Nature 226(5241): 106. (1970). "Locusts in retreat." Nature 227(5256): 340. (1970). "Energetics in the tropics." Nature 228(5266): 17. (1970). "NSF declared sole heir." Nature 228(5269): 308-9. (1984). "Nuclear winter: ICSU project hunts for data." Nature 309(5969): 577. (2000). "Think globally, act cautiously." Nature 403(6770): 579. (2000). "Critical politics of carbon sinks." Nature 408(6812): 501. (2000). "Bush's science flashpoints." Nature 408(6815): 885. (2001). "Shooting the messenger." Nature 412(6843): 103. (2001). "Shooting the messenger." Nature 412(6843): 103. (2002). "A climate for change." Nature 416(6881): 567. (2002). "Maintaining the climate consensus." Nature 416(6883): 771. (2002). "Leadership at Johannesburg." Nature 418(6900): 803. (2002). "Trust and how to sustain it." Nature 420(6917): 719. (2003). "Climate come-uppance delayed." Nature 421(6920): 195. (2003). "Climate come-uppance delayed." Nature 421(6920): 195. (2003). "Yes, we have no energy policy." Nature 422(6927): 1. (2003). "Don't create a climate of fear." Nature 425(6961): 885. (2004). "Leapfrogging the power grid." Nature 427(6976): 661. (2004). "Carbon impacts made visible." Nature 429(6987): 1. (2004). "Dragged into the fray." Nature 429(6990): 327. (2004). "Fighting AIDS is best use of money, says cost-benefit analysis." Nature 429(6992): 592. (2004). "Ignorance is not bliss." Nature 430(6998): 385. (2004). "States versus gases." Nature 430(6999): 489. -

PRACTICAL LAB II : DEVELOPMENT BIOLOGY and EVOLUTION, GENETICS and MICROBIOLOGY Author: Dr

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY [Accredited with ‘A+’ Grade by NAAC (CGPA:3.64) in the Third Cycle and Graded as Category–I University by MHRD-UGC] (A State University Established by the Government of Tamil Nadu) KARAIKUDI – 630 003 Directorate of Distance Education M.Sc. [Zoology] II - Semester 350 24 PRACTICAL LAB II : DEVELOPMENT BIOLOGY AND EVOLUTION, GENETICS AND MICROBIOLOGY Author: Dr. Ngangbam Sarat Singh, Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology, Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Government Arts College, Yanam, Puducherry (UT) “The copyright shall be vested with Alagappa University” All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Alagappa University, Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Alagappa University, Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT. LTD. E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 • Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi 110 055 • Website: www.vikaspublishing.com • Email: [email protected] Work Order No. -

XXII Jornadas De La Sociedad Española De Paleontología

XXII Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Paleontología y simposios de los proyectos PICG 493, 503, 499, y 467 Libro de Resúmenes E. Fernández-Martínez (Editora) Diseño y maquetación: Antonio Buil Dibujos de portada y contraportada: Cristina García Núñez © Universidad de León Secretariado de Publicaciones © Los autores I.S.B.N. : 84-9773-293-6 Depósito Legal: LE-1584-2006 Impresión: Universidad de León. Servicio de Imprenta XXII Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Paleontología Organizado por: Universidad de León Sociedad Española de Paleontología Con la colaboración de: Caja España Programa Internacional de Correlación Geológica (IUGS, UNESCO) Conjunto Paleontológico de Teruel - Dinópolis Diputación de León Ayuntamiento de León Ayuntamiento de Los Barrios de Luna Ayuntamiento de La Pola de Gordón Comité Organizador Dra. Esperanza M. Fernández Martínez (Secretaria). Universidad de León. Dra. Rosa Mª. Rodríguez González. Universidad de León. Dra. Mª Amor Fombella Blanco. Universidad de León. Dr. Manuel Salesa Calvo. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC). Sra. Mª Dolores Pesquero Fernández. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC). Coordinación de Proyectos PICG Dr. Patricio Domínguez. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Dr. José Antonio Gámez Vintaned. Universidad de Zaragoza. Dr. J. Ignacio Valenzuela Ríos. Universidad de Valencia. Dra. Ana Márquez-Aliaga. Universidad de Valencia. Coordinación de excursiones Excursión A Dr. Jenaro Luis García-Alcalde. Universidad de Oviedo. Dra. Isabel Méndez-Bedia. Universidad de Oviedo. Dr. Luis Pedro Fernández. Universidad de Oviedo. Dra. Esperanza M. Fernández Martínez. Universidad de León. Dr. Francisco M. Soto Fernández. Universidad de Oviedo. Excursión B Dr. Carlos Aramburu. Universidad de Oviedo. Dr. Miguel Arbizu Senosiain. Universidad de Oviedo. -

Rockhounds Herald

The official bulletin of the Dothan Gem & Mineral Club, Inc. Rockhounds Herald 920 Yorktown Road, Dothan, AL 36301-4372 www.wiregrassrockhounds.com April 2014 Words from… The President What a show we had!!! If you weren’t there, you missed a first-rate event. Despite the torrential rain on Sunday, we had a great crowd both days and the vendors all seemed very, very happy. Some even remarked that they preferred the Farm Center to the venue we’ve been using. I have to agree. With the lower ceiling and better lighting, the space was more intimate and one truly befitting a gem show---the sparkle of all the shiny stuff didn’t get lost in a cavernous expanse of empty space like it always did at the gymnasium. There will be lots to discuss as we review the weekend’s events at the meeting on April 27th. Bring your observations and your comments as to what could have and should have been done differently. With the 2014 show out of the way, it’s never too early to start planning for 2015.☺ Looking a couple months ahead to the start of the summer break, if you expect to find yourself vacationing in the Great Smokies you might want to skip a day of singing stage shows and drive a couple hours northeast of Gatlinburg to Gray, TN. There you’ll find the East Tennessee State University (ETSU) & General Shale Natural History Museum Visitor Center and Gray Fossil Site. (There’s a short profile about the center on page 6.) ETSU has quite a collection of fossils, and the cool part is they literally dug them up from their own backyard. -

Evidence of a False Thumb in a Fossil Carnivore Clarifies the Evolution of Pandas

Evidence of a false thumb in a fossil carnivore clarifies the evolution of pandas Manuel J. Salesa*†, Mauricio Anto´ n*, Ste´ phane Peigne´ ‡, and Jorge Morales* *Departamento de Paleobiologı´a,Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Jose´Gutie´rrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain; and ‡Laboratoire de Ge´obiologie, Biochronologie et Pale´ontologie Humaine, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unite´Mixte de Recherche 6046, Universite´de Poitiers, 40 Avenue du Recteur Pineau, 86022 Poitiers, France Edited by F. Clark Howell, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved October 7, 2005 (received for review June 12, 2005) The ‘‘false thumb’’ of pandas is a carpal bone, the radial sesamoid, and thus uncommon in larger, terrestrial carnivores. Simocyon, which has been enlarged and functions as an opposable thumb. If about the size of a puma, is the largest known arctoid carnivore the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and the red panda with such lumbar morphology, likely reflecting a scansorial (Ailurus fulgens) are not closely related, their sharing of this habit, meaning that the animal would forage on the ground but adaptation implies a remarkable convergence. The discovery of would readily climb when necessary (5). Many features of the previously unknown postcranial remains of a Miocene red panda appendicular skeleton indicate climbing abilities and the lack of relative, Simocyon batalleri, from the Spanish site of Batallones-1 cursorial adaptations. The scapula has a large process for the (Madrid), now shows that this animal had a false thumb. The radial teres major muscle, shared only with the arboreal kinkajou sesamoid of S. -

Tennessee – Paleontology and Geology Overview

Learning Series: Basic Rockhound Knowledge Tennessee – Paleontology and Geology Overview Geologic Periods The Precambrian: In the Precambrian, the future state of Tennessee lay beneath marine waters far south of the equator. Sediments that accumulated Quaternary on the sea floor were later metamorphosed and intruded by molten material during mountain building. These igneous and metamorphic rocks are now Tertiary exposed in the Blue Ridge Mountains along the eastern border of Tennessee. Cretaceous The Paleozoic: During this time, Tennessee lay along the southern margin of future North America as the continent drifted north toward the equator. Shallow sea water covered the state through most of this interval (Cambrian Jurassic through Early Carboniferous), and the sea floor was home to a variety of animals, including brachiopods, trilobites, crinoids, bryozoans, and corals. Triassic In the Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian), mountain-building to the east produced vast amounts of sediment that was carried by westward-flowing Permian rivers into the shallow sea. Huge, swampy deltas developed. These low- lying areas were lush with scale trees, horsetail rushes, and other plants Carboniferous that would eventually produce Tennessee’s coal deposits. The state lay above sea level by the end of the era, and erosion outpaced deposition. Devonian The Mesozoic: Tennessee lay above sea level for much of the Mesozoic, and erosion outpaced deposition. The sea advanced across the western Silurian part of the state in the Cretaceous, bringing a return to marine conditions in that region. Crinoids, clams, oysters, and snails thrived in the shallow Ordovician waters, while dinosaurs walked the dry land farther east. Cambrian The Cenozoic: During the Early Cenozoic (Tertiary), warm, tropical marine waters periodically advanced across western Tennessee, while the rest of Precambrian the state remained above sea level. -

Highlights • Cavilignum Pratchettii Is a New Neogene Angiosperm From

!"#$%"#$&'( ! •! !"#$%$&'()*+,"-./0--$$!"#!$!%&'!(&)*&%&!$%*")#+&,-!.,)-!&$#/&,%!0&%%&##&&1! 234353! ! •! !"#$%$&'()!"#!6$#&7!)%!.)8,9:;$-6&,&7!.)##"<!&%7):$,+#!'"/;!)+&%!*&,-"%$/")%! +),! ! •! !"#$%$&'()!:$%%)/!6&!7&."%"/"=&<>!:<$##"."&7!'"/;"%!$%*")#+&,-#3! ! •! !"#$%$&'()!"#!/;&!.",#/!&?/"%:/!+<$%/!-$:,).)##"<!*&%8#!.,)-!@,$>!A)##"<!4"/&3! ! !"#$%&'"()")(##%*"'+,(-./0#"/'0/'#'+&%+1"."+'2"&.3(+")/(4"&5'"'./*6"7*%(-'+'"8/.6" 9(##%*":%&';"<'++'##'';"=>:>!>;"%#",'#-/%?',".#"!"#$%$&'()*+,"-./0--$$*1'+>"'&"#0>"+(@>" !"#$%$&'()"%#"/'0/'#'+&',"?6"-%/-$*./"&("(?*(+1"'+,(-./0#"&5.&"5.@'"."&/$+-.&'".0'3;"." 4$-/(+.&'"?.#';".+,"."#4((&5"($&'/"#$/).-'>"<5'"'+,(-./0"2.**"5.#"&5/''"*.6'/#>"<5'" ($&'/4(#&"*.6'/"%#"()"$+-'/&.%+"-(40(#%&%(+>"<5'"%++'/"2.**"#&/$-&$/'"%#")%?/($#;"2%&5".+" ($&'/"*.6'/"()"/.,%.**6A(/%'+&',")%?'/#".+,".+"%++'/"*.6'/"()"-%/-$4)'/'+&%.**6A(/%'+&'," )%?'/#>"<5'"'+,(-./0#"&60%-.**6"5.@'")($/"-5.4?'/#"B*(-$*'#C",%@%,',"?6"&5%-D"#'0&.E"&2(" +.//(2"-.+.*#"0'+'&/.&'"&5'"#'0&.")/(4"&5'".0'3"&("&5'"?.#'"()"'.-5"'+,(-./0>"<5'" *(-$*'#"./'"(0'+".0%-.**6>"F'-.$#'"+("'@%,'+-'"()"#&/$-&$/'#"&5.&"4.6"5.@'"#'.*',"&5'" -5.4?'/#"2.#")($+,;"!"#$%$&'()*%#"%+&'/0/'&',".#"5.@%+1"(0'+"1'/4%+.&%(+"0(/'#>" !0%-.**6A(/%'+&',;"(0'+"1'/4%+.&%(+"0(/'#"4(#&"(?@%($#*6"#$11'#&".+".))%+%&6"2%&5"&5'" .+1%(#0'/4").4%*6":640*(-.-'.';"?$&"'+,(-./0#"()":640*(-.-'.'",%))'/")/(4" !"#$%$&'()*%+"#'@'/.*"-/%&%-.*"-5./.-&'/%#&%-#"B'>1>;"2.**"5%#&(*(16;"0/'#'+-'"()"."?.#.*" 0%&C>"G5%*'"#'@'/.*"(&5'/"1/($0#"B'>1>;"!+.-./,%.-'.';"H(/+.*'#C"0/(,$-'",/$0.-'($#" )/$%&#"2%&5"'+,(-./0#"-(40./.?*'"%+"#(4'"-5./.-&'/%#&%-#"&("&5(#'"()"!"#$%$&'();"+(+'" -

A New Species of Teleoceras from the Late Miocene Gray Fossil Site, with Comparisons to Other North American Hemphillian Species Rachel A

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 A New Species of Teleoceras from the Late Miocene Gray Fossil Site, with Comparisons to Other North American Hemphillian Species Rachel A. Short East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Paleobiology Commons Recommended Citation Short, Rachel A., "A New Species of Teleoceras from the Late Miocene Gray Fossil Site, with Comparisons to Other North American Hemphillian Species" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1143. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1143 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A New Species of Teleoceras from the Late Miocene Gray Fossil Site, with Comparisons to Other North American Hemphillian Species A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Geosciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Geosciences by Rachel A. Short May 2013 Steven C. Wallace, chair Blaine W. Schubert Jim I. Mead Keywords: Gray Fossil Site, Teleoceras, Morphology, Post-cranial 1 ABSTRACT A New Species of Teleoceras from the Late Miocene Gray Fossil Site, with Comparisons to Other North American Hemphillian Species by Rachel A. Short A thorough morphological description of Teleoceras material from the Gray Fossil Site, Gray, Tennessee is provided. -

Comparative Genomics Reveals Convergent Evolution Between the Bamboo-Eating Giant and Red Pandas

Comparative genomics reveals convergent evolution between the bamboo-eating giant and red pandas Yibo Hua,1,QiWua,1, Shuai Maa,b,1, Tianxiao Maa,b,1, Lei Shana, Xiao Wanga,b, Yonggang Niea, Zemin Ningc, Li Yana, Yunfang Xiud, and Fuwen Weia,b,2 aKey Laboratory of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; bUniversity of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; cWellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, United Kingdom; and dStraits (Fuzhou) Giant Panda Research and Exchange Center, Fuzhou 350001, China Edited by Steven M. Phelps, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Joan E. Strassmann December 15, 2016 (received for review August 19, 2016) Phenotypic convergence between distantly related taxa often mirrors genetic base” (13), and Stephen J. Gould later featured the new adaptation to similar selective pressures and may be driven by genetic digit in the title of his popular 1980 book, “The Panda’sThumb” convergence. The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca)andred (14). In the red panda, the pseudothumb also facilitates arboreal panda (Ailurus fulgens) belong to different families in the order Car- locomotion (15). Despite this widespread interest, its genetic basis nivora, but both have evolved a specialized bamboo diet and adaptive has remained elusive. These shared characteristics between giant pseudothumb, representing a classic model of convergent evolution. and red pandas represent a classic model of convergent evolution However, the genetic bases of these morphological and physiological under presumably the same environmental pressures. convergences remain unknown. -

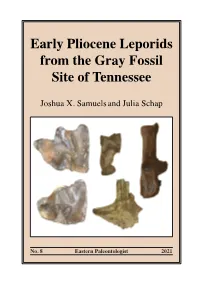

Early Pliocene Leporids from the Gray Fossil Site of Tennessee

Early Pliocene Leporids from the Gray Fossil Site of Tennessee Joshua X. Samuels and Julia Schap No. 8 Eastern Paleontologist 2021 EASTERN PALEONTOLOGIST Board of Editors ♦ The Eastern Paleontologist is a peer-reviewed jour- nal that publishes articles focusing on the paleontology Richard Bailey, Northeastern University, Boston, MA of eastern North America (ISSN 2475-5117 [online]). Manuscripts based on studies outside of this region that David Bohaska, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, provide information on aspects of paleontology within DC this region may be considered at the Editor’s discretion. Michael E. Burns, Jacksonville State University, Jack- ♦ Manuscript subject matter - The journal welcomes sonville, AL manuscripts based on paleontological discoveries of Laura Cotton, Florida Museum of Natural History, terrestrial, freshwater, and marine organisms and their Gainesville, FL communities. Manuscript subjects may include paleo- Dana J. Ehret, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ zoology, paleobotany, micropaleontology, systematics/ Robert Feranec, New York State Museum, Albany, NY taxonomy and specimen-based research, paleoecology (including trace fossils), paleoenvironments, paleobio- Steven E. Fields, Culture and Heritage Museums, Rock geography, and paleoclimate. Hill, SC ♦ It offers article-by-article online publication for Timothy J. Gaudin, University of Tennessee, Chatta- prompt distribution to a global audience. nooga, TN ♦ It offers authors the option of publishing large files Russell Graham, College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, such as data tables, and audio and video clips as online University Park, PA supplemental files. Alex Hastings, Virginia Museum of Natural History, ♦ Special issues - The Eastern Paleontologist wel- Martinsville, VA comes proposals for special issues that are based on conference proceedings or on a series of invitational Andrew B. -

15 June 2021 Aperto

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino KEY INNOVATIONS AND EVOLUTIONARY CONSTRAINTS DURING THE EVOLUTION OF AVIAN TAKE-OFF This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/1703196 since 2019-05-29T09:44:33Z Publisher: Andy Farke; Amber MacKenzie; Jess Miller-Camp Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 06 October 2021 See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308474671 Key innovations and evolutionary constraints during the evolution of avian flight Conference Paper · October 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 82 2 authors: Loredana Macaluso Emanuel Tschopp Università degli Studi di Torino American Museum of Natural History 5 PUBLICATIONS 3 CITATIONS 50 PUBLICATIONS 222 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Ten Sleep Wyoming Jurassic dinosaurs View project Diplodocid sauropod diversity across the Morrison Formation View project All content following this page was uploaded by Loredana Macaluso on 23 September 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. mammaliaform fossils are the consequence of the labile chondrogenesis of the otic Poster Session II (Thursday, October 27, 2016, 4:15–6:15 PM) capsule relative to the cochlear nerve(s) and its cochlear ganglion, which also contributed KEY INNOVATIONS AND EVOLUTIONARY CONSTRAINTS DURING THE to the varying degrees of the cochlear canal curvature and coiling among different EVOLUTION OF AVIAN FLIGHT mammalian clades.