Emigrant Gap Field Trip Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By David S. Harwood, G. Reid Fisher, Jr., and Barbara J. Waugh

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-2341 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE DUNCAN PEAK AND SOUTHERN PART OF THE CISCO GROVE 7-1/2' QUADRANGLES, PLACER AND NEVADA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA By David S. Harwood, G. Reid Fisher, Jr., and Barbara J. Waugh LOCATION AND ACCESS Province (fig. 1). The fault-bounded Feather River peridotite belt lies about 15 km west of the map area (fig. 1) and This map covers an area of 123 km2 on the west marks a major tectonic boundary separating rocks of the slope of the Sierra Nevada, an uplifted and west-tilted northern Sierra terrane from Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks range in eastern California (fig. 1). The area is located to the west that were accreted to the northern Sierra 20 km west of Donner Pass, which lies on the east es terrane during the Mesozoic (Day and others, 1985). A carpment of the range, and about 80 km east of the Great variety of plutonic rocks, ranging in age from Middle Jurassic Valley Province. Interstate Highway 80 is the major route to Early Cretaceous, intrude the metamorphic rocks in over the range at this latitude and secondary roads, which the map area. The metamorphic and plutonic rocks are spur off from this highway, provide access to the northern unconformably overlain by erosional remnants of T er part of the area. None of the secondary roads crosses tiary volcanic rocks and scattered Quaternary glacial the deep canyon cut by the North Fork of the American deposits. River, however, and access to the southern part of Metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks in the the area is provided by logging roads that spur off from northern Sierra terrane have been divided into sequences the Foresthill Divide Road that extends east from Auburn that are separated by regional unconformities. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE Chinese Railroad Workers’ Experience Exhibit | 4th Grade | 2020 CHINESE RAILROAD WORKERS’ EXPERIENCE EXHIBIT The nation’s first Transcontinental Railroad, completed on May 10, 1869, had a profound impact on the nation’s development. More than ninety percent of the Central Pacific Railroad’s workforce was Chinese. They were vital to the successful completion of the railroad that changed life in America forever. Based on the latest research, this teacher’s guide provides you with background information and engaging student activities. 1. Summit Tunnel, No. 119. WHAT’S INSIDE THIS GUIDE - Background information on the building of the Transcontinental railroad & the Chinese railroad workers’ experience fueled by the latest research. - Transcontinental Railroad Timeline - Glossary of Terms - Resources for further reading CaliforniaStateRailroad.Museum - Student Activities [email protected] (916) 323-9280 California State Railroad Museum Chinese Railroad Workers’ Experience Exhibit Teacher’s Guide 4th Grade California State Railraod Museum Interpretation & Education Research & Writing: Debbie Hollingsworth, M.A. Graphic Design & Interpretation: Kim Whitfield, M.A. First Edition, 2020. California Teaching Standards: 4.4.1, 4.4.3, RI 4.1, 4.3. 4.6, W 4.1, 4.2, 4.3 © 2020 California State Parks & California State Railroad Museum californiarailroad.museum/education www.parks.ca.gov Questions about this handbook should be directed to: California State Railroad Museum Interpretation & Education California State Parks 111 I Street, Sacramento, California 95814 Phone: (916) 323-9280 [email protected] Teacher’s Guide: Chinese Railroad Workers’ Experience Exhibit 2020 3 INTRODUCTION The nation’s first transcontinental Experience offers visitors a view railroad, completed on May 10, of a labor force that achieved the 1869, had a profound impact impossible and was subsequently on the nation’s development. -

A Historical Context and Methodology for Evaluating Trails, Roads, and Highways in California

A Historical Context and Methodology for Evaluating Trails, Roads, and Highways in California Prepared by The California Department of Transportation Sacramento, California ® ® © 2016 California Department of Transportation. All Rights Reserved. Cover photography provided Caltrans Headquarters Library. Healdsburg Wheelmen photograph courtesy of the Healdsburg Museum. For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate formats upon request. Please call: (916) 653-0647 Voice, or use the CA Relay Service TTY number 1-800-735-2929 Or write: Chief, Cultural Studies Office Caltrans, Division of Environmental Analysis P.O. Box 942874, MS 27 Sacramento, CA 94274-0001 A HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND METHODOLOGY FOR EVALUATING TRAILS, ROADS, AND HIGHWAYS IN CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Cultural Studies Office Division of Environmental Analysis California Department of Transportation Sacramento 2016 © 2016 California Department of Transportation. All Rights Reserved. OTHER THEMATIC STUDIES BY CALTRANS Water Conveyance Systems in California, Historic Context Development and Evaluation Procedures (2000) A Historical Context and Archaeological Research Design for Agricultural Properties in California (2007) A Historical Context and Archaeological Research Design for Mining Properties in California (2008) A Historical Context and Archeological Research Design for Townsite Properties in California (2010) Tract Housing In California, 1945–1973: A Context for National Register Evaluation (2013) A Historical Context and Archaeological Research Design for Work Camp Properties in California (2013) MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) prepared this study in response to the need for a cohesive and comprehensive examination of trails, roads, and highways in California, and with a methodological approach for evaluating these types of properties for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). -

The First Transcontinental Railroad Adapted From: "The First Transcontinental Railroad." the First Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad Adapted from: "The First Transcontinental Railroad." The First Transcontinental Railroad. Web. 07 July 2016. http://www.tcrr.com/ The First Transcontinental Railroad in the United States was built in the 1860s. It linked the railway network of the eastern U.S. coast with California. The main line was completed on May 10, 1869. The U.S. economy increased because of the railroad and the lines connected to it. It allowed many people and products to quickly and inexpensively travel across the country. It also changed the way of life for the Native Americans and changed the environment. The rail line was an important goal of President Abraham Lincoln and was completed four years after his death. An important reason to build the railroad at this time was to connect California to the Union during the American Civil War. When completed, the Transcontinental Railroad replaced the slower and more dangerous land routes used by wagon train or stagecoach. It also ended the need for the difficult sea routes around the southern tip of South America. In fact, travel time from coast to coast was reduced from six months to one week. The railroad is considered by some to be the greatest technological feat of the 19th century. The central route followed the Oregon, Mormon and California Trails used by early settlers. The new line began in Omaha, Nebraska and followed the Platte River. It crossed the Rocky Mountains at South Pass in Wyoming. Then it continued through northern Utah and Nevada before crossing the Sierras to Sacramento, California. -

Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental

When the Locomotive Puffs: Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental Railroad Builders, 1863-69 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Leland K. Wood August 2009 © 2009 Leland K. Wood. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled When the Locomotive Puffs: Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental Railroad Builders, 1863-69 by LELAND K. WOOD has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Patrick S. Washburn Professor of Journalism Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract WOOD, LELAND K., Ph.D., August 2009, Journalism When the Locomotive Puffs: Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental Railroad Builders, 1863-69 (246 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Patrick S. Washburn The dissertation documents public-relations practices of officers and managers in two companies: the Central Pacific Railroad with offices in Sacramento, California, and the Union Pacific Railroad with offices in New York City. It asserts that sophisticated and systematic corporate public relations were practiced during the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, fifty years before historians generally place the beginning of such practice. Documentation of the transcontinental railroad practices was gathered utilizing existing historical presentations and a review of four archives containing correspondence and documents from the period. Those leading the two enterprises were compelled to practice public relations in order to raise $125 million needed to construct the 1,776-mile-long railroad by obtaining and keeping federal loan guarantees and by establishing and maintaining an image attractive to potential bond buyers. -

Summit. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-203 195 No 52

Stereo Page Geographic Ima~ graph number Title Geographic area sequence num er msts? of album Aaoss Blue Canyon, looking East. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-130 158 No 33 Aaoss Blue Canyon, looking West. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-133 161 No 34 Advance of Civilization. End of Track near Iron Point. Humboldt River, The Desert G-322 321 No 83 Advance of Civilization. Scene on the Humboldt Desert . Humboldt River, The Desert G-323 322 No 84 Almve in Palisades, Ten Mile Canyon. Humboldt River, The Desert G-340 339 No 88 Alkali Flat. Construction train in distance. Humboldt River, The Desert G-313 312 No 81 All Aboard for Virginia City. Wells, Fargo &: Co.'s Express. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-I80 217 No 46 Alta from the North. Altitude 3,635 feet. 69 miles from Saaamento. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-I02 68 No 26 Alta from the South. Altitude 3,635 feet. 69 miles from Saaamento. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-I0l 67 No 26 American Peak, in Spring, View near the Pass, Western Summit. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-203 195 No 52 American River and Canyon from Cape Hom. River below Railroad Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-78 44 Yes 20 1,400 feet. 57 miles from Sac. American River Bridge, 400 ft. long. Valley of the Saaamento G-4 144 No 1 American River Bridge. Railroad around Cape Hom, 1,400 feet above. Sierra Nevada Mountains, Western Summit G-79 229 Yes 21 American River, from Green Bluffs. -

Pioneer Monument at 100 We’Re Pretty Parochial at the Donner Summit Historical Society’S Heirloom Offices

June, 2018 issue #118 Pioneer Monument at 100 We’re pretty parochial at the Donner Summit Historical Society’s Heirloom offices. We focus on Donner Summit history, of which there is a lot and so no need to go elsewhere for good stories. Coming up this month, though, on June 9 (see the ad later in this issue), is the one hundredth anniversary of the Pioneer Monument at the Donner State Park. At first look, that has nothing to do with us since it’s down at Donner Lake, miles away, and a thousand feet lower in elevation. Since we’re addressing the subject here in the Heirloom, though, you can guess that there is a connection to Donner Summit. The Pioneer Monument celebrates the achievement of thousands of emigrants who came over Donner Summit on their way to new opportunities and new lives in California. They’d just endured almost unimaginable hardships crossing the deserts of Utah and Nevada and must have been so glad when they reached the Truckee Meadows (today’s Reno) where there was water, grass, and rest. And then they approached the Sierra. To Edwin Bryant in 1846 the Sierra was a "formidable and apparently impassable barrier...” David Hudson (1845) said, “When we reached Sierra Nevada mountains they looked terrible." William Tustin (1846) said that when they saw the Sierra “every heart was filled with terror at the awful site [sic].” Wm. Todd (1845) said the Sierra were "Tribulations in the extreme.” We’ve carefully acquired a long list of emigrant quotes so we could continue, but you have the idea. -

A. A. Hart Stereographs of the Central Pacific Railroad: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8b85bds Online items available A. A. Hart Stereographs of the Central Pacific Railroad: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2014 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. A. A. Hart Stereographs of the photCL 184 1 Central Pacific Railroad: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: A. A. Hart Stereographs of the Central Pacific Railroad Dates (inclusive): approximately 1864-1869 Collection Number: photCL 184 Creator: Hart, Alfred A., 1816-1908 Extent: 372 photographs in 2 boxes : prints on card mounts ; mounts 9 x 18 cm (stereograph format) + 20 copy prints in 1 additional box Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains 372 stereographic photographs (including some variants and duplicates) by photographer A. A. Hart (1816-1908) that document the construction of the western half of first transcontinental railroad by the Central Pacific Railroad between 1864 and 1869. Hart served as the Central Pacific's first official photographer, and his images chronicle the advancement of the railroad over 742 miles from Newcastle, California, through the Sierra Nevada Mountains and into Nevada and Utah. Language: English. Note: Finding aid last updated on September 19, 2014. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION Location and Setting Background Information National Historic Trail Designation National Park Service Responsibilities Bureau of Land Management Responsibilities Trail Description Major Problems and Issues PART II - MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES AND CONSTRAINTS General Management Objectives Management Constraints PART III – OREGON/MORMON TRAIL GENERAL MANAGEMENT POLICY Limitations of the Management Plan Split-Estate Lands Federal Minerals - Private or State Surface Federal Surface - Private or State Minerals Protective Corridor Concept Establishment of Corridor Requirements for Corridors Segments Mineral Management Mineral Leasing Salable Minerals Locatable Minerals Valid Existing Rights Trail Marking Inventory Requirements National Register of Historic Places Monitoring and Use Supervision Special Recreation Use Permits (SRUP) Off-Road Vehicle (ORV) Designation Impacts on Private Landowners Facilities Interpretation Brochure Standard Land Management Procedures Volunteers Land Tenure Adjustment Cooperative Management Agreements Other Private Sector Involvement Cross-Country Trekking Industrial Use of the Trails PART IV - THE MANAGEMENT PROGRAM Introduction Management Actions for Trails Torrington to Independence Rock Segment Sweetwater/South Pass Segment Lombard Ferry Segment Bridger Segment Bear River Divide Segments Table of Contents Mormon/California Trail Segment Seminoe Cutoff Lander Road Sublette Cutoff Kinney Cutoff Slate Creek Cutoff Dempsey-Hockaday Cutoff Blacks Fork Cutoff Maintenance Administration -

Camping and Picnicking Yuba River Ranger District Hwy 20, Bowman Rd, Interstate 80 Areas Tahoe National Forest

Camping and Picnicking Yuba River Ranger District Hwy 20, Bowman Rd, Interstate 80 Areas Tahoe National Forest Welcome campgrounds in the Highway 20 corridor and Interstate 80 corridor have limited first-come, first-serve Welcome to the Tahoe National Forest, where each year availability, but may be reserved. Reservations can be over several million visitor days are spent enjoying the made online at www.recreation.gov or by calling scenic variety and clean air of the high Sierra. These 877-444-6777. public lands are dedicated to the conservation of the forests, water, grazing areas, wildlife, and recreational Unless noted, each campsite has a table and fire ring, or opportunities. The Forest name, taken from the famed cooking stove/grill. Many campsites also have bear Lake Tahoe, is probably from a Washoe Indian word proof food lockers. meaning Big Water. In order to protect soil and vegetation resources, family The Tahoe National Forest is located northeast of campsites are limited to six persons or one immediate Sacramento in the Central Sierra Nevada Mountains. family per site. Several highways, including Interstate 80; State Highways 20, 49, 89, and 267; and Forest roads, provide Group Campgrounds excellent access to most portions of the Forest. Skillman, Faucherie and Big Bend group Campgrounds The central Sierra Nevada Mountains offer scenic beauty are available by reservation only. Reservations can be and an attractive climate that have made the area an made online at www.recreation.gov or by calling outstanding year-round center for outdoor recreation. 877-444-6777. Elevations within the Forest vary from about 1,500 feet in the foothills to over 9,000 feet at the Sierra Crest. -

Sword in the Stone

April 1, 2018 issue #116 Sword in the Stone - Donner Summit Edition Sometimes there are long lines. People wait patiently their turns in summer heat, or the fall chill before the snow, their turns to try to remove the sword from the stone. As they wait they share their stories and why it will be they for whom the sword will loosen. All have failed. The story is that he (she) who pulls the sword from the stone inherits the dragons’ treasure (see “The Dragons of Donner Summit” in the April, ’14 Heirloom) but no one has been able to extract the sword from the stone. Here is where rigorous historical research should be of use. No one knows for sure that sword extraction and treasure go together. No one knows what the source of that story is so the veracity is questionable. There is a sword in the stone near Lake Angela however as you can see in the above photograph too. There were dragons on Donner Summit (see the April first,’ 14 Heirloom) and there was treasure. No one doubts any of that. No one, of the many, who has tried to pull out the sword has been successful – clearly no one has been in possession of the right characteristics. But what are the right characteristics? What happens when the sword is extracted? Despite searches, nothing has turned up satisfying answers. We do know that the snows of winter fall each year on the sword in the stone on Donner Summit and it remains buried until spring. ©Donner Summit Historical Society April 1, 2018 issue 116 page 1 Story Locations in this Issue In This Issue Sword in the Stone pg 1 Maiden's -

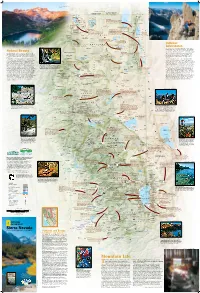

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt.