Captivated Pages Corrected:Captivated Pages 12/2/09 13:37 Page 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan in and out of Time

06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page iii J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan In and Out of Time A Children’s Classic at 100 Edited by Donna R. White C. Anita Tarr CHILDREN’S LITERATURE ASSOCIATION CENTENNIAL STUDIES SERIES, NO. 4 THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Oxford 2006 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page v Contents Introduction vii Donna R. White and C. Anita Tarr Part I: In His Own Time 1 Child-Hating: Peter Pan in the Context of Victorian Hatred 3 Karen Coats 2 The Time of His Life: Peter Pan and the Decadent Nineties 23 Paul Fox 3 Babes in Boy-Land: J. M. Barrie and the Edwardian Girl 47 Christine Roth 4 James Barrie’s Pirates: Peter Pan’s Place in Pirate History and Lore 69 Jill P. May 5 More Darkly down the Left Arm: The Duplicity of Fairyland in the Plays of J. M. Barrie 79 Kayla McKinney Wiggins Part II: In and Out of Time—Peter Pan in America 6 Problematizing Piccaninnies, or How J. M. Barrie Uses Graphemes to Counter Racism in Peter Pan 107 Clay Kinchen Smith v 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page vi vi Contents 7 The Birth of a Lost Boy: Traces of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House 127 Rosanna West Walker Part III: Timelessness and Timeliness of Peter Pan 8 The Pang of Stone Words 155 Irene Hsiao 9 Playing in Neverland: Peter Pan Video Game Revisions 173 Cathlena Martin and Laurie Taylor 10 The Riddle of His Being: An Exploration of Peter Pan’s Perpetually Altering State 195 Karen McGavock 11 Getting Peter’s Goat: Hybridity, Androgyny, and Terror in Peter Pan 217 Carrie Wasinger 12 Peter Pan, Pullman, and Potter: Anxieties of Growing Up 237 John Pennington 13 The Blot of Peter Pan 263 David Rudd Part IV: Women’s Time 14 The Kiss: Female Sexuality and Power in J. -

Alice Syfy Mini Series Torrent Download WE LOVE INDONESIA

alice syfy mini series torrent download WE LOVE INDONESIA. Neverland Mini Series on SYFY Torrent : Syfy gamble huge featuring its two-night authentic miniseries occasion Neverland and yes it paid back. The actual best of Part One particular involving Neverland came A couple of.6 000 0000 overall readers from 9-11 p.michael. in Saturday nighttime, upwards Five percent make up the wire network's most recent miniseries Alice (the bring up to date about Alice in Wonderland) via 09. Describes associated with Alice drew A couple of.Three or more trillion viewers. watch Neverland miniseries today, a prequel from Peter Pan and to watch Neverland streaming online and available in torrent links, Megavideo, Sockshare, VideoBB, Videozer, and more. Neverland Mini Series on SYFY. In the advertiser-coveted grown ups 18-49 group, Neverland -- which usually began Syfy's next yearly Countdown to be able to Christmas time - - averaged practically One million audiences. In the elderly 25-54 demo, the two-hour telecast enticed One.Tough luck million readers. The final a part of Neverland broadcast about Syfy about Friday nighttime; ratings to the telecast is going to be accessible overdue Thursday or even earlier Friday. It is just a prequel to T.Mirielle. Barrie's traditional Peter Pan history glaring Rhys Ifans, Keira Knightley, Ould - Friel, Bob Hoskins, Raoul Trujillo and also Charlie Rowe because Chris Skillet. Neverland is manufactured by Dublin-based Similar Films on behalf of MNG Motion pictures, in colaboration with Syfy and also Atmosphere Films Hi-def and is written by RHI Amusement Watch Neverland Mini Series on SYFY Online Free or Download Neverland Mini Series on SYFY. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Study Guide for Educators

Study Guide for Educators A Musical Based on the Play by Sir James M. Barrie Music by Mark Charlap Additional Music by Jule Styne Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh Additional Lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green Originally Adapted and Directed by Jerome Robbins 1 This production of Peter Pan is generously sponsored by: Ng & Ng Dental and Eye Care Joan Gellert-Sargen Jerry & Sharon Melson Ron Tindall, RN Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. -

Finding Neverland

BARRIE AND THE BOYS 0. BARRIE AND THE BOYS - Story Preface 1. J.M. BARRIE - EARLY LIFE 2. MARY ANSELL BARRIE 3. SYLVIA LLEWELYN DAVIES 4. PETER PAN IS BORN 5. OPENING NIGHT 6. TRAGEDY STRIKES 7. BARRIE AND THE BOYS 8. CHARLES FROHMAN 9. SCENES FROM LIFE 10. THE REST OF THE STORY Barrie and the Llewelyn-Davies boys visited Scourie Lodge, Sutherland—in northwestern Scotland—during August of 1911. In this group image we see Barrie with four of the boys together with their hostess. In the back row: George Llewelyn Davies (age 18), the Duchess of Sutherland and Peter Llewelyn Davies (age 14). In the front row: Nico Llewelyn Davies (age 7), J. M. Barrie (age 51) and Michael Llewelyn Davies (age 11). Online via Andrew Birkin and his J.M. Barrie website. After their mother's death, the five Llewelyn-Davies boys were alone. Who would take them in? Be a parent to them? Provide for their financial needs? Neither side of the family was really able to help. In 1976, Nico recalled the relief with which his uncles and aunts greeted Barrie's offer of assistance: ...none of them [the children's uncles and aunts] could really do anything approaching the amount that this little Scots wizard could do round the corner. He'd got more money than any of us and he's an awfully nice little man. He's a kind man. They all liked him a good deal. And he quite clearly had adored both my father and mother and was very fond of us boys. -

The Lost Boys of Bird Island

Tafelberg To the lost boys of Bird Island – and to all voiceless children who have suffered abuse by those with power over them Foreword by Marianne Thamm Secrets, lies and cover-ups In January 2015, an investigative team consisting of South African and Belgian police swooped on the home of a 37-year-old computer engineer, William Beale, located in the popular Garden Route seaside town of Plettenberg Bay. The raid on Beale came after months of meticulous planning that was part of an intercontinental investigation into an online child sex and pornography ring. The investigation was code-named Operation Cloud 9. Beale was the first South African to be arrested. He was snagged as a direct result of the October 2014 arrest by members of the Antwerp Child Sexual Exploitation Team of a Belgian paedophile implicated in the ring. South African police, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Heila Niemand, cooperated with Belgian counterparts to expose the sinister network, which extended across South Africa and the globe. By July 2017, at least 40 suspects had been arrested, including a 64-year-old Johannesburg legal consultant and a twenty-year-old Johannesburg student. What police found on Beale’s computer was horrifying. There were thousands of images and videos of children, and even babies, being abused, tortured, raped and murdered. In November 2017, Beale pleaded guilty to around 19 000 counts of possession of child pornography and was sentenced to fifteen years in jail, the harshest punishment ever handed down in a South African court for the possession of child pornography. -

Published Version

PUBLISHED VERSION Maggie Tonkin From 'Peter Panic' to proto-modernism: the case of J.M. Barrie Changing the Victorian Subject, 2014 / Tonkin, M., Treagus, M., Seys, M., Crozier De Rosa, S. (ed./s), pp.259-281 © 2014 The Contributors This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. PERMISSIONS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ http://hdl.handle.net/2440/84284 13 From ‘Peter Panic’ to proto-Modernism: the case of J.M. Barrie Maggie Tonkin The author may be dead as far as Roland Barthes is concerned, but the news is yet to hit the street. Probably nothing speaks more loudly of the gap between academic literary criticism and the culture of reading outside the academy than the latter’s continuing obsession with the author. Barthes’s claim that the author is neither the originator nor the final determiner of textual meaning has assumed the status of orthodoxy in scholarly poetics. Whilst the early austerity has faded somewhat, such that discussion of the historical specificity of the author is no longer scorned in literary studies, the Romantic privileging of the author as the ‘fully intentional, fully sentient source of the literary text, as authority for and limitation on the “proliferating” meanings of the text’, as Andrew Bennett puts it (55), has never regained its former currency. -

Tracy Wells Big Dog Publishing

Tracy Wells Adapted from the 1911 novel by J.M. Barrie Illustration by Alice B. Woodward Big Dog Publishing Peter Pan and Wendy 2 Copyright © 2013, Tracy Wells ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Peter Pan and Wendy is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and all of the countries covered by the Universal Copyright Convention and countries with which the United States has bilateral copyright relations including Canada, Mexico, Australia, and all nations of the United Kingdom. Copying or reproducing all or any part of this book in any manner is strictly forbidden by law. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or videotaping without written permission from the publisher. A royalty is due for every performance of this play whether admission is charged or not. A “performance” is any presentation in which an audience of any size is admitted. The name of the author must appear on all programs, printing, and advertising for the play and must also contain the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Big Dog/Norman Maine Publishing LLC, Rapid City, SD.” All rights including professional, amateur, radio broadcasting, television, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved by Big Dog/Norman Maine Publishing LLC, www.BigDogPlays.com, to whom all inquiries should be addressed. Big Dog Publishing P.O. Box 1401 Rapid City, SD 57709 Peter Pan and Wendy 3 For my children. -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H. -

Verge 10 Anna Richardson Broken Fragments

Verge 10 Anna Richardson Broken Fragments of Immortality: Why People Will Always Love Peter Pan Elbow-deep into my research, I asked my fifty-four year old mother why she liked Peter Pan. She was visiting for the weekend, and while discussing my project had expressed her deep sentiments for Peter Pan. I was curious. I simply asked what it was about the story, and about the boy himself, that she found so appealing. She told me that she hadn’t wanted to grow up as a child, that Neverland had been so full of adventure and possibility. Frowning slightly, she said, “You know, I just was Peter Pan.” Chances are that many people, of varying ages, will answer similarly when asked about their feelings for Peter Pan. The boy who wouldn’t grow up has a firm grasp on the hearts and minds of generations of people across the globe who, being human, would give anything to stop time from steamrolling ahead, even if just for a few days. What is so fascinating about this phenomenon is that the story, the play, the movies, and the boy himself are inherently tragic, ridden with dilemmas and life-altering decisions. Peter is a “betwixt and between,” as author J. M. Barrie called him, part boy, part bird, part specter (Wiggins 95). Indeed, Peter Pan was not simply a character inked into being, living only on the page. He first came into existence via the childhood games of Barrie and the five Llewelyn Davies boys with whom Barrie had a strong personal relationship, becoming their main caregiver after their parents died. -

Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci

S.No. Film Name Genre Director 1 Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci . 2 The Dreamers (2003) Bernardo Bertolucci . 3 Stealing Beauty (1996) H1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 4 The Sheltering Sky (1990) I1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 5 Nine 1/2 Weeks (1986) Adrian Lyne . 6 Lolita (1997) Stanley Kubrick . 7 Eyes Wide Shut – 1999 H1.M Stanley Kubrick . 8 A Clockwork Orange [1971] Stanley Kubrick . 9 Poison Ivy (1992) Katt Shea Ruben, Andy Ruben . 1 Irréversible (2002) Gaspar Noe 0 . 1 Emmanuelle (1974) Just Jaeckin 1 . 1 Latitude Zero (2000) Toni Venturi 2 . 1 Killing Me Softly (2002) Chen Kaige 3 . 1 The Hurt Locker (2008) Kathryn Bigelow 4 . 1 Double Jeopardy (1999) H1.M Bruce Beresford 5 . 1 Blame It on Rio (1984) H1.M Stanley Donen 6 . 1 It's Complicated (2009) Nancy Meyers 7 . 1 Anna Karenina (1997) Bernard Rose Page 1 of 303 1 Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1964) Russ Meyer 9 . 2 Vixen! By Russ Meyer (1975) By Russ Meyer 0 . 2 Deep Throat (1972) Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato 1 . 2 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) Elia Kazan 2 . 2 Pandora Peaks (2001) Russ Meyer 3 . 2 The Lover (L'amant) 1992 Jean-Jacques Annaud 4 . 2 Damage (1992) Louis Malle 5 . 2 Close My Eyes (1991) Stephen Poliakoff 6 . 2 Casablanca 1942 H1.M Michael Curtiz 7 . 2 Duel in the Sun (film) (1946) I1.M King Vidor 8 . 2 The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) H1.M David Lean 9 . 3 Caligula (1979) Tinto Brass 0 . -

Peter and Alice

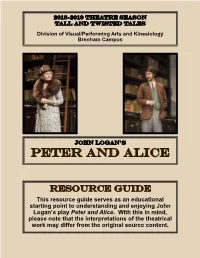

2018-2019 Theatre Season Tall and Twisted Tales Division of Visual/Performing Arts and Kinesiology Brenham Campus John Logan’s Peter and Alice Resource Guide This resource guide serves as an educational starting point to understanding and enjoying John Logan’s play Peter and Alice. With this in mind, please note that the interpretations of the theatrical work may differ from the original source content. Performances February 14 - 16 7 p.m. February 17 2 p.m. High School Preview Performances February 14 & 15 1 p.m. Dr. W.W. O’Donnell Performing Arts Center Brenham, Texas Tickets can be purchased in advance online at www.blinn.edu/BoxOffice, by calling 979-830-4024, or by emailing [email protected] Directed by TCCSTA Play Festival Entry Brad Nies Peter and Alice is Blinn College-Brenham’s entry to the 2019 Texas Community College Speech and Technical Theatre Direction by Theatre Association Play Festival. This state- Kevin Patrick wide organization has been actively enriching the lives of Texas Community College students since Costume, Makeup, and Hair Design by 1922. The annual Play Festival celebrates the art Jennifer Patrick of theatre in an atmosphere of friendliness and respect and provides an opportunity for two-year Produced by Special Arrangement with colleges to share their work in a festival setting, Samuel French, Inc. receiving awards and important feedback from educated theatre critics. Synopsis This remarkable new play is based on the real-life meeting of Alice Hargreaves and Peter Davies at the 1932 opening of a Lewis Carroll exhibition in a London bookshop.