Introducing the Flourish Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digraphs Th, Sh, Ch, Ph

At the Beach Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph • Generalization Words can have two consonants together that are pronounced as one sound: southern, shovel, chapter, hyRJlen. Word Sort Sort the list words by digraphs th, sh, ch, and ph. th ch 1. shovel 2. southern 1. 11. 3. northern 4. chapter 2. 12. 5. hyphen 6. chosen 7. establish 3. 13. 8. although 9. challenge 10. approach 4. 14. 11. astonish 12. python 5. 15. 13. shatter 0 14. ethnic 15. shiver sh 16. Ul 16. pharmacy .,; 6. ..~ ~ 17. charity a: !l 17. .c 18. china CJ) a: 19. attach 7. ~.. 20. ostrich i 18. ~.. 8. "'5 .; £ c ph 0 ~ C) 9. 19. ;ii" c: <G~ ,f 0 E 10. 20. CJ) ·c i;: 0 0 ~ + Home Home Activity Your child is learning about four sounds made with two consonants together, called ~ digraphs. Ask your child to tell you what those four sounds are and give one list word for each sound. DVD•62 Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph Name Unit 2Weel1 1Interactive Review Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph shovel hyphen challenge shatter charity southern chosen approach ethnic china northern establish astonish shiver attach chapter although python pharmacy ostrich Alphabetize Write the ten list words below in alphabetical order. ethnic python ostrich charity hyphen although chapter establish northern southern 1. 6. 2. 7. c, 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. Synonyms Write the list word that has the same or nearly the same meaning. 11. surprise 16. drugstore 12. dare 17. break 13. shake 18. fasten "'u £ c 14. 19. dig 0 pottery ·;; " 15. -

Sound Production T 'Thick' D 'The' S 'Sh' Z 'Azure' Ts 'Ch' Dz 'J' N 'Thing

Language & the Mind Sound LING240 Summer Session II 2005 Production Lecture 5 Sounds How you look to a phonetician How you look to a phonetician Nasal Cavity Palate Velum Oral Cavity Tongue Glottis (vocal folds) Lips, teeth etc. T ‘thick’ D ‘the’ S ‘sh’ Forget Spelling! Z ‘azure’ Sounds 䍫 Spelling tS ‘ch’ dZ ‘j’ N ‘thing’ / ‘ uh- oh’ 1 One Sound - Many Characters One Sound - Many Characters he e seas ea too oo threw ew believe ie amoeba oe to o lieu ieu Caesar ae key ey see ee machine i clue ue shoe oe people eo seize ei through ough Interantioanl Phonetic Alphabet: [i] IPA: [u] One Character - Many Sounds One Sound - Multiple Letters dame e shoot S dad Q either D character father a k deal call ç i Thomas t village I, ´ physics f many E rough f One Letter - 0, 1, 2 Sounds Differences across Languages mnemonic • English: judge, juvenile, Jesus [dZ] psychology resign • Spanish: jugar, Jesus [h] ghost • German: Jugend, jubeln, Jesus [j] island whole • French: Jean, j’accuse, jambon [Z] debt cute [kjuwt] 2 Major division: consonants vs vowels • Consonantal sounds: narrow or complete closure somewhere in the vocal tract. • Vowels: very little obstruction in the vocal tract. Can form the basis of syllables (also possible for some consonants). Describing Speech Sounds Where does the Air Flow? • Where/how is the air flowing? nasal/oral, stop, fricative, liquid etc. • Where is the air-flow blocked? labial, alveolar, palatal, velar etc. • What are the vocal folds doing? voiced vs. voiceless Block it at the velum Where does the air go? Your vocal tract again 3 N Block it at the velum Tongue against velum again Where does the air go? Now raise the velum Now raise the velum to block the air... -

First : Arabic Transliteration Alphabet

E/CONF.105/137/CRP.137 13 July 2017 Original: English and Arabic Eleventh United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names New York, 8-17 August 2017 Item 14 a) of the provisional agenda* Writing systems and pronunciation: Romanization Romanization System from Arabic letters to Latinized letters 2007 Submitted by the Arabic Division ** * E/CONF.105/1 ** Prepared by the Arabic Division Standard Arabic System for Transliteration of Geographical Names From Arabic Alphabet to Latin Alphabet (Arabic Romanization System) 2007 1 ARABIC TRANSLITERATION ALPHABET Arabic Romanization Romanization Arabic Character Character ٛ GH ؽٔيح ء > ف F ا } م Q ة B ى K د T ٍ L س TH ّ M ط J ٕ ػ N % ٛـ KH ؿ H ٝاُزبء أُوثٛٞخ ك٢ ٜٗب٣خ أٌُِخ W, Ū ٝ ك D ١ Y, Ī م DH a Short Opener ه R ā Long Opener ى Z S ً ā Maddah SH ُ ☺ Alif Maqsourah u Short Closer ٓ & ū Long Closer ٗ { ٛ i Short Breaker # ī Long Breaker ظ ! ّ ّلح Doubling the letter ع < - 1 - DESCRIPTION OF THE NEW ALPHABET How to describe the transliteration Alphabet: a. The new alphabet has neglected the following Latin letters: C, E, O, P, V, X in addition to the letter G unless it is coupled with the letter H to form a digraph GH .(اُـ٤ٖ Ghayn) b. This Alphabet contains: 1. Latin letters which have similar phonetic letters in Arabic : B,T,J,D,R,Z,S,Q,K,L,M,N,H,W,Y. ة، ،د، ط، ك، ه، ى، ً، م، ى، ٍ، ّ، ٕ، ٛـ، ٝ، ١ 2. -

Isolation & Syllables

/sh/ & /ch/ & /zh/ & /j/ (jump) ISOLATION & SYLLABLES /sh/: This is called the “quiet” sound because it sounds like you are telling someone to be quiet. You pucker your lips, put your tongue up against your hard palate (the roof of your mouth), and blow. Add vowel sounds after the sound to produce syllables. (shay, she, shy, show, shoe) /zh/: This sound is just like the “sh” sound, but with your voice turned on. You pucker your lips, put your tongue up against your hard palate (the roof of your mouth), turn your voice on, and blow. Once “sh” sounds good, practice turning the voice on and off “sh-zh-sh-zh”. Add vowel sounds after the sound to produce syllables. (zhay, zhe, zhy, zhow, zhoe) /ch/: The “sh” sound usually comes first and is easier to produce. The “sh” sound can lead to a “ch” sound. Starting with a “sh” the tip on the tongue pushes against the hard palate (the roof of your mouth) and then goes back down (like a door opening and closing). Alternate “sh-ch-sh-ch”. The “ch” sound is a blend of the “t” sound and “sh” sound. Alternate “t-sh, t-sh, t-ch” to get a “ch” sound. Add vowel sounds after the sound to produce syllables. (chay, chee, chie, cho, chew) /j/: The “j” sound is almost the same as the “ch” with the voice turned on. Once “ch” sounds good, practice turning the voice on and off “ch-j-ch-j-ch”. The “j” sound is also a blend of the “d” sound and “y” sound. -

SH Series C Compiler USER's MANUAL HITACHI

Hitachi Microcomputer Support Software SH Series C Compiler USER’S MANUAL HITACHI ADE-702-095 HS0700CLCU1SE The Copyright Statement Preface This manual explains the facilities and operating procedures for the SH series C compiler (Ver. 2.0). The C compiler translates source programs written in C into relocatable object programs or assembly programs for Hitachi SH7000 series RISC microcomputers. This manual consists of four parts and appendixes. The information contained in each part is summarized below. (1) PART I OVERVIEW AND OPERATIONS The overview sections cover the following: V C compiler functions W Developing procedures The operation sections cover the following: X How to invoke the C compiler Y Optional functions Z Listings created by the C compiler (2) PART II PROGRAMMING This part explains the limitations of the C compiler and the special factors in object program execution which should be considered when creating a program. (3) PART III SYSTEM INSTALLATION This part explains the requirements when installing an object program generated by the C compiler on a system. They are the object program being written in ROM and memory allocation. In addition, specifications of the low-level interface routine must be made by the user when using standard I/O library and memory management library. (4) PART IV ERROR MESSAGES This part explains the error messages corresponding to compilation errors and the standard library error messages corresponding to run time errors. This manual corresponds to operating systems that function on UNIX, MS-DOS, or IBM-PC systems. In this manual, operating systems functioning on MS-DOS or IBM-PC systems are referred to as PC systems. -

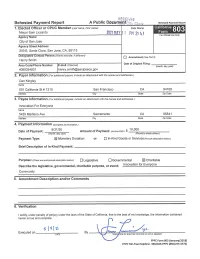

S H U\ a Executed on by DATE S1GN;^URE of ELECTED OFFICER OR CPUC MEMBER

RECEiVhil- Behested Payment Report Behested Payment Report A Public Dbcnir7l%ntQ,^., CAnr-'yi 1. Elected Officer or CPUC Member (Last name, First name) Date Stamp California < Mayor Sam Liccardo m\ HAY IForm ’ ! I PM 2: 41 For Official Use Only Agency Name City of San Jose Agency Street Address 200 E. Santa Clara, San Jose, CA, 95113 Designated Contact Person (Name and title, if different) I I Amendment fSee Part 5; Henry Smith Date of Original Filing: Area Code/Phone Number E-mail (Optional) (month, day, year) 4085354831 [email protected] 2. Payor Information (For additional payors, include an attachment with the names and addresses.) Dan Kingley Name 601 California St# 1310 San Francisco CA 94108 Address City state Zip Code 3. Payee Information (For additional payees, include an attachment with the names and addresses.) Innovation For Everyone Name 5429 Madison Ave Sacramento CA 95841 Address City State Zip Code 4. Payment Information (Complete aiiinformation.) 8/31/20 10,000 Date of Payment: Amount of Payment: (in-KindFMV) $ (month, day, year) (Round to whole dollars.) Payment Type: [HI Monetary Donation or □ In-Kind Goods or Services (Provide descnpuon below.) Brief Description of In-Kind Payment: Purpose: (Check one and provide description below.) □ Legislative □ Governmental HI Charitable Innovation for Everyone Describe the legislative, governmental, charitable purpose, or event: Community 5. Amendment Description and/or Comments 6. Verification I certify, under penalty of perjury under the laws of the State of California, that to the best of my knowledge, the information contained herein is true and complete. s h U\ A Executed on By DATE S1GN;^URE OF ELECTED OFFICER OR CPUC MEMBER FPPC Form 803 (January/ZOlS) FPPCToll-Free Helpline: 866/ASK-FPPC (866/275-3772). -

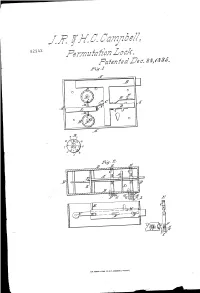

JR SH . C Carriel

JRSH . C Carriel , 9294X . PermatahonPatenter Lock .Tec . 23, 183 . 5 . Ing. 1 | B . 07 E . O ? 61 N INNNANNA ? / CE SNISSNISSSSS N AM. PHOTO- LITH p. CO. N . Y. ( DSBORNE' S PROCESS .) ANG? WW SohnRead . CimbellyBAYA Henry Cine Charleton; cthof Middle Cohinoniealth ofmaka ; .., het ons' » . * . ' niet. opitting Patent ** goodcondi parkofi. LohidulirforderlineSohedule the same referred containing to in1 . anithis dorintadescription Satu Satina thewordiof aid making. ne . hon Calambile and Fenny Barw boarddew thimoclinica thirinprominent Dior Like and other fastening Brit InKnown all, to , whom that ive thür; John Gruent: Read shallCambell come .and Henry Care Canbeltideithaf bharlantowi w the county of Middleen anal Homm inwealth of Alaiheetti: haresitoow . now and singer wirfrënémentm thi. Look for Doors or suih dikugustining , ana thifilering is a füll and eväit: descripdimme thetheim unitrattenin " "and operation of the maid Staihine as insinded or improved en este tien the firinciple upon .si hih 'we gromial our improvinent. - do rapeistäin painte of the arrangenuint are to be fromahd. to coincide dedore. The bolt onnike shot or withdrawn, whih pomen 3 -.-.-.. cowalu. co doranges that withoni orme. clue to the guidestby ül bicoimeo almost hopelefo do attempi them recoñinection , and Thische. saw .bu given hij ai combinatim ofurtainbegirao oni het . the outside . His known for incijale me improve the construction . og that, I . Pa represent the eneloveing care of the lock ! B .the boltorbolis . the orfebar- running avrofor the one, and medicinechinese cpaineeksrig. the hoola Dikoontebi- bar ho ceritain thieadeher into which the king. co . to be application. E the sering behind saciel ontoh .dur , burring against the printo . -

Flourishing During the Teen Years

Brigham Young University Family Studies Center Research Brief Flourishing During the Teen Years: Why “Not Being Bad” Isn’t Good Enough Laura Padilla-Walker Associate Professor and Associate Director, School of Family Life, Brigham Young University Madison Memmott-Elison MFHD Master’s Student, School of Family Life, Brigham Young University When parents and the popular youth to be successful, focusing media talk about teenagers, on the development of these four more often than not the focus strengths is an important starting The Research is on the bad stuff, the problem point, and parents, leaders, and behaviors like risky sex, drinking, educators all play a key role in Much of what we present and drug use. While such a focus helping youth develop these in this brief is based is certainly warranted, the vast behaviors. on a unique, ten-year majority of teenagers make it longitudinal study called through these years without AN ESSENTIAL PRECURSOR The Flourishing Families experiencing serious problems, TO FLOURISHING: and those who do struggle often SELF-CONTROL Project (FFP). The FFP stop participating in problem consisted of 500 families behaviors after the teen years. An important precursor to any of living in the northwestern But the avoidance of such the qualities in the “Flourishing United States and was behaviors does not necessarily Youth” sidebar below (e.g., conducted by a group of mean the presence of positive feel confident, connect with faculty at Brigham Young behaviors. In other words, “not others), is self-control. Most of being bad” is not good enough. us are familiar with a child who University. -

Digraph Sh Whiteboard Activities See Instructional Routines, Pages 29–32, for Additional Lesson Details and Support

IWB Interactive Digraph sh Whiteboard Activities See Instructional Routines, pages 29–32, for additional lesson details and support. IWB This icon indicates that the CD includes an interactive whiteboard version of the activity that can be used for small-group or whole-class learning. Introduce the Sound-Spelling: Tell children that when the letters s 1 and h appear together in a word, they usually stand for a new sound—the /sh/ sound. Write the letters sh on the board. Have children write the letters sh several Build Words times as they say /sh/. Model Blending: Write the words hop, shop, sell, shell, dish, trash, and 2 splash on the board. Model blending the words sound by sound. Run your finger under each letter as you say the sound. Emphasize the sound ofsh in words containing that digraph spelling. Have children repeat. Blend Words: Use Blend Words: Digraph sh, page 242, to have children Sound-Spelling Word Sort 3 chorally blend the words on each line. Model, as needed. Children can then use the lists for further independent practice. Also encourage children to complete the Do More! activities. Build Words: Using the letter cards on Build Words: Digraph sh, page 243, 4 have children build the following words in sequence: hot, shot, shop, hop, hip, ship, sip, sick, sock, shock, shack, back, bat, fat, fit, fish, wish, dish, dash, rash, rush. Spell Words Then have children complete the activities on the page. IWB Sort Words: Use Sound-Spelling Word Sort: Digraph sh, page 244, to have 5 children work with partners to sort the words by their sound-spellings. -

Sh(X) = B) La Fonction Cosinus Hyperbolique : Ch(X)

Devoir de mathématiques pour le vendredi 23 octobre Correction. Exercice 1 ex − e−x 1) a) La fonction sinus hyperbolique : sh(x) = 2 ex − (−e−x) ex + e−x Pour tout x 2 , sh0(x) = = . R 2 2 Or la fonction exp est toujours strictement positive, donc sh0(x) > 0. Ainsi • Limite en +1 : lim ex = +1 et lim −e−x = 0 x!+1 x!+1 x −∞ +1 donc, par somme de limites, lim sh(x) = +1. x!+1 sh0(x) + • Limite en −∞ : lim ex = 0 et lim −e−x = −∞ x→−∞ x→−∞ +1 donc, par somme de limites, lim sh(x) = −∞. x→−∞ sh −∞ Parité : pour tout x 2 R, −x 2 R et e−x − e−(−x) e−x − ex −ex + e−x sh(−x) = = = = −sh(x) 2 2 2 Donc sh est impaire. ex + e−x b) La fonction cosinus hyperbolique : ch(x) = 2 ex − e−x Pour tout x 2 , ch0(x) = = sh(x). R 2 Or sh(0) = 0 et, d'après ci-dessus, sh est strictement croissante sur R, donc nous avons le tableau de signe suivant : De même que ci-dessus, par somme de limites, nous obtenons : x −∞ 0 +1 • lim ch(x) = +1. x!+1 ch0(x) = sh(x) − 0 + • lim ch(x) = +1. x→−∞ +1 +1 ch 1 Parité : pour tout x 2 R, −x 2 R et e−x + e−(−x) e−x + ex ex + e−x ch(−x) = = = = ch(x) 2 2 2 Donc ch est paire. 2) Soit x 2 R xé. ex + e−x ex − e−x ex + e−x + ex − e−x 2ex a) ch(x) + sh(x) = + = = = ex. -

Empowering Teachers

LA.2.1.4.1 EMPOWERING TEACHERS Phonics Instructional Routine: Read and Write Words with Consonant Digraphs Preparation/Materials: Consonant Digraph Word Cards and Consonant Digraph Chart (provided), paper, and pencil for student(s). - Italicized type is what the teacher does - Bullet (•) and bolded type are what the teacher and - Bold type is what the teacher says student(s) say in unison - Regular type is what the student(s) say - ALL CAPS notes an emphasis in speech - Teacher or student slides finder under - Letters and words in print are in “quotation marks” 2 underlined letter(s) or word(s) - Sounds are noted using / / TEACHER EXPLAINS TASK We are going to read words with consonant digraphs. TEACHER MODELS TASK Display Consonant Digraph Chart. Look at this chart. Each consonant digraph has two consonants. The second consonant is an “h”. This is important. One consonant followed by the letter h makes a new sound. Listen and watch. The letters “s” “h” say /sh/. The letters “c” “h” say /ch/. The letters “t” “h” say /th/. The letters “w” “h” say /wh/. Display the word card “shut”. Together, the letters “s” “h” say /sh/. I will sound out and read the word. /sh-u-t/, “shut” The word “shut” begins with the digraph /sh/. Now I will place the word “shut” under the digraph /sh/. Place “shut” on the chart. Repeat the above sequence with words “thin”, “when”, and “chop”. I read words that start with consonant digraphs. TEACHER & STUDENTS PRACTICE TASK TOGETHER Display Consonant Digraph Chart. Look at this chart. Each consonant digraph has two consonants. -

The Latin Alphabet Page 1 of 58 the Latin Alphabet

The Latin Alphabet Page 1 of 58 The Latin Alphabet The Latin alphabet of 23 letters was derived in the 600's BC from the Etruscan alphabet of 26 letters, which was in turn derived from the archaic Greek alphabet, which came from the Phoenician. The letters J, U, and W of the modern alphabet were added in medieval times, and did not appear in the classical alphabet, except that J and U could be alternative forms for I and V. A comparison of the Greek and Latin alphabets shows the close relation between the two. Green letters are those introduced later, after the alphabets had been adopted, and red letters are those that were eliminated from the archaic alphabet. The digamma, which represented a 'w' sound in Greek was adopted for the different Latin sound 'f' that did not occur in Greek. The gamma was written C in Etruscan, and represented both the hard 'g' and 'k' sounds in Latin, which was confusing. Latin also used the K for the 'k' sound at that time, but the C spelling became popular. Z was a sound not used in Latin, so it was thrown out of the alphabet and replaced by a modified C, a C with a tail, for the 'g' sound. Eventually, K became vestigial in Latin, used only for a few words like Kalendae and Kaeso (a name). Gaius was also spelled Caius, and its abbreviation was always C. Koppa became the model for Q, which in Latin was always used in the combination QV, pronounced 'kw,' a sound that does not occur in Greek.