As for Me and My House: Zhaawanaash and Methodism at Berens River, 1874–1883

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous-Led, Land-Based Programming Facilitating Connection to the Land and Within the Community

Indigenous-Led, Land-Based Programming Facilitating Connection to the Land and within the Community By Danielle R. Cherpako Social Connectedness Fellow 2019 Samuel Centre for Social Connectedness www.socialconnectedness.org August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Section 1: Introduction --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 1.1 Research and outreach methodology Section 2: Misipawistik Cree Nation: History & Disruptions to the Land ----------------------------- 5 2.1 Misipawistik Cree Nation 2.2 Settler-colonialism as a disruption to the connection to the land 2.3 The Grand Rapids Generating Station construction and damage to the land 2.4 The settlement of Hydro workers and significant social problems 2.5 The climate crisis as a disruption to the connection to the land 2.6 Testimonies from two local Elders, Alice Cook and Melinda Robinson Section 3: Reconnecting to the Land using Land-Based Programming ------------------------------ 16 3.1 Misipawistik Pimatisiméskanaw land-based learning program 3.1 (a) Providing culturally relevant education and improving retention of students, 3.1 (b) Revitalizing Cree culture, discovering identity and reconnecting to the land, 3.1 (c) Addressing the climate crisis and creating stewards of the land, 3.1 (d) Building community connectedness (Including input from Elders and youth). 3.2 Misipawistik’s kanawenihcikew Guardians program Section 4: Land-Based Programming in Urban School Divisions -------------------------------------- 25 4.1 -

Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes

Zawadzka Temagami Area Rock Art 159 Beyond the Sacred: Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes Dagmara Zawadzka The rock art of the Temagami area in northeastern Ontario represents one of the largest concentrations of this form of visual expression on the Canadian Shield. Created by Algonquian-speaking peoples, it is an inextricable part of their cultural landscape. An analysis of the distribution of 40 pictograph sites in relation to traditional routes known as nastawgan has revealed that an overwhelming majority are located on these routes, as well as near narrows, portages, or route intersections. Their location seems to point to their role in the navigation of the landscape. It is argued that rock art acted as a wayfinding landmark; as a marker of places linked to travel rituals; and, ultimately, as a sign of human occupation in the landscape. The tangible and intangible resources within which rock art is steeped demonstrate the relationships that exist among people, places, and the cultural landscape, and they point to the importance of this form of visual expression. Introduction interaction in the landscape. It may have served as The boreal forests of the Canadian Shield are a boundary, resource, or pathway marker. interspersed with places where pictographs have Therefore, it may have conveyed information that been painted with red ochre. Pictographs, located transcends the religious dimension of rock art and most often on vertical cliffs along lakes and rivers, of the landscape. are attributed to Algonquian-speaking peoples and This paper discusses the rock art of the attest, along with petroglyphs, petroforms, and Temagami area in northeastern Ontario in relation lichen glyphs, to a tradition that is at least 2000 to the traditional pathways of the area known as years old (Aubert et al. -

Thistle Indian-Trader.Pdf

THE UNIVERS]TY OF MANITOBA INDIAN--TRADER RELATIONS: AN ETHNOH]STORY OF WESTERN WOODS CREE.-HUDSONIS BAY COMPANY TRADER CONTACT IN THE CUMBERLAND HOUSE--THE PAS REGION TO 1840 A thesis subnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Master of Art s in the Indívidual Tnterdisciplinary Programne (Anthropology, History, Educat i on) by Paul Clifford Thistle .Tu 1v 19 8 3 INDIAN--TRADDR REI-ATIONS: AN ETHNOII ISTORY 0F I¡]ESTERN WOODS CREE--HUDSONTS BAY COMPANY TRADER CONTACT IN THE CUMBERLAND HOUSE--THE PAS REGION TO I84O by PauI Cl ifford Thistle A tlìesis submitted to the Faculty of G¡aduate Studies ol the University of Manitobâ in partial fulfillment of the requirenìer.ìts of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS @ 1983 Pe¡missjon has been granted to the LIBRARY OF THE UNIVER- SITY OF MANITOBA to lend or sell copies of this thesis. to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilnr this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and UNIVERSITy MICROFILMS to publish an abstract of this thesis. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or other- wise reproduced without the autho¡'s w¡ittelr perurissiotr. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT vl1 CHAPTER I ]NTRODUCT ION 1 The Prob 1em 1 Purpose 3 Scope 4 S igni ficance 5 Method 11 The o ry T4 (i) Ethnic/Race Relations Theory 16 (ii) Ethnicity Theory 19 (iii) Culture Change and Acculturat i on Theory 22 Sumrnary Discussion 26 II ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE RELATION z8 Introduction . -

Chapter 4 – Project Setting

Chapter 4 – Project Setting MINAGO PROJECT i Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 4. PROJECT SETTING 4-1 4.1 Project Location 4-1 4.2 Physical Environment 4-2 4.3 Ecological Characterization 4-3 4.4 Social and Cultural Environment 4-5 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map ......................................................................................................... 4-1 Figure 4.4-1 Communities of Interest Surveyed ....................................................................................... 4-6 MINAGO PROJECT ii Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4. PROJECT SETTING 4.1 Project Location The Minago Nickel Property (Property) is located 485 km north-northwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and 225 km south of Thompson, Manitoba on NTS map sheet 63J/3. The property is approximately 100 km north of Grand Rapids off Provincial Highway 6 in Manitoba. Provincial Highway 6 is a paved two-lane highway that serves as a major transportation route to northern Manitoba. The site location is shown in Figure 4.1-1. Source: Wardrop, 2006 Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map MINAGO PROJECT 4-1 Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4.2 Physical Environment The Minago Project is located within the Nelson River sub-basin, which drains northeast into the southern end of the Hudson Bay. The Minago River and Hargrave River catchments, surrounding the Minago Project Site to the north, occur within the Nelson River sub-basin. The William River and Oakley Creek catchments at or surrounding the Minago Project Site to the south, occur within the Lake Winnipeg sub-basin, which flows northward into the Nelson River sub-basin. The topography in these watersheds varies between elevation 210 and 300 m.a.s.l. -

Treaty 5 Treaty 2

Bennett Wasahowakow Lake Cantin Lake Lake Sucker Makwa Lake Lake ! Okeskimunisew . Lake Cantin Lake Bélanger R Bélanger River Ragged Basin Lake Ontario Lake Winnipeg Nanowin River Study Area Legend Hudwin Language Divisi ons Cobham R Lake Cree Mukutawa R. Ojibway Manitoba Ojibway-Cree .! Chachasee R Lake Big Black River Manitoba Brandon Winnipeg Dryden !. !. Kenora !. Lily Pad !.Lake Gorman Lake Mukutawa R. .! Poplar River 16 Wakus .! North Poplar River Lake Mukwa Narrowa Negginan.! .! Slemon Poplarville Lake Poplar Point Poplar River Elliot Lake Marchand Marchand Crk Wendigo Point Poplar River Poplar River Gilchrist Palsen River Lake Lake Many Bays Lake Big Stone Point !. Weaver Lake Charron Opekamank McPhail Crk. Lake Poplar River Bull Lake Wrong Lake Harrop Lake M a n i t o b a Mosey Point M a n i t o b a O n t a r i o O n t a r i o Shallow Leaf R iver Lewis Lake Leaf River South Leaf R Lake McKay Point Eardley Lake Poplar River Lake Winnipeg North Etomami R Morfee Berens River Lake Berens River P a u i n g a s s i Berens River 13 ! Carr-Harris . Lake Etomami R Treaty 5 Berens Berens R Island Pigeon Pawn Bay Serpent Lake Pigeon River 13A !. Lake Asinkaanumevatt Pigeon Point .! Kacheposit Horseshoe !. Berens R Kamaskawak Lake Pigeon R !. !. Pauingassi Commissioner Assineweetasataypawin Island First Nation .! Bradburn R. Catfish Point .! Ridley White Beaver R Berens River Catfish .! .! Lake Kettle Falls Fishing .! Lake Windigo Wadhope Flour Point Little Grand Lake Rapids Who opee .! Douglas Harb our Round Lake Lake Moar .! Lake Kanikopak Point Little Grand Pigeon River Little Grand Rapids 14 Bradbury R Dogskin River .! Jackhead R a p i d s Viking St. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

2010-2011 Annual Report

First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority CONTACT INFORMATION Head Office Box 10460 Opaskwayak, Manitoba R0B 2J0 Telephone: (204) 623-4472 Facsimile: (204) 623-4517 Winnipeg Sub-Office 206-819 Sargent Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3E 0B9 Telephone: (204) 942-1842 Facsimile: (204) 942-1858 Toll Free: 1-866-512-1842 www.northernauthority.ca Thompson Sub-Office and Training Centre 76 Severn Crescent Thompson, Manitoba R8N 1M6 Telephone: (204) 778-3706 Facsimile: (204) 778-3845 7th Annual Report 2010 - 2011 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 16 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 FIRST NATION AGENCIES OF NORTHERN MANITOBA ABOUT THE NORTHERN AUTHORITY First Nation leaders negotiated with Canada and Manitoba to overcome delays in implementing the AWASIS AGENCY OF NORTHERN MANITO- Aboriginal Justice Inquiry recommendations for First Nation jurisdiction and control of child welfare. As a result, the First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority (Northern BA Authority) was established through the Child and Family Services Authorities Act, proclaimed in November 2003. Cross Lake, Barren Lands, Fox Lake, God’s Lake Narrows, God’s River, Northlands, Oxford House, Sayisi Dene, Shamattawa, Tataskweyak, War Lake & York Factory First Nations Six agencies provide services to 27 First Nation communities and people in the surrounding areas in Northern Manitoba. They are: Awasis Agency of Northern Manitoba, Cree Nation Child and Family Caring Agency, Island Lake First Nations Family Services, Kinosao Sipi Minosowin Agency, CREE NATION CHILD AND FAMILY CARING Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation FCWC and Opaskwayak Cree Nation Child and Family Services. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

1 Métis Fur Trade Employees, Free Traders, Guides and Scouts

Métis Fur Trade Employees, Free Traders, Guides and Scouts – Darren R. Préfontaine, Patrick Young, Todd Paquin and Leah Dorion Module Objective: In this module, the students will learn about the Métis’ role in the fur trade, their role as free traders, and their role as guides and scouts – positions, which contributed immensely to the development of Canada. These various economic activities contributed to the Métis worldview since many Métis remained loyal fur trade employees, while others desired to live and make an independent living for themselves and their families. They will also learn that the Métis comprised a large and distinct element within the fur trade in which they played a number of key and essential roles. The students will also appreciate that while the Métis were largely a product of the fur trade, they gradually became their own people and resisted attempts to be controlled or manipulated by outside economic forces. Finally, the students will also learn that the Métis' knowledge of the country and of First Nations languages and customs made them superb guides, scouts, and interpreters. As Metis Elder Madeline Bird explains it, the Metis are mediators, forming a bridge between conflicting actions, dogmas, and beliefs. They emerged as geographers of experience and persuasion, mastering competing situations to the benefit of both land and isolated cultures – serving as trailblazers, middlemen, interpreters, negotiators and constitutional arbitrators1. Métis Labour in the Fur Trade The Métis played perhaps the most important role in the fur trade because they were the human links between First Nations and Europeans. The Métis were employed in every facet of the fur trade and this fact alone ensured that they would remain tied to the fortunes of a trade, which was outside their control. -

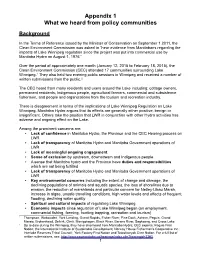

Appendix 1 What We Heard from Policy Communities

Appendix 1 What we heard from policy communities Background In the Terms of Reference issued by the Minister of Conservation on September 1 2011, the Clean Environment Commission was asked to “hear evidence from Manitobans regarding the impacts of Lake Winnipeg regulation since the project was put into commercial use by Manitoba Hydro on August 1, 1976.” Over the period of approximately one month (January 12, 2015 to February 18, 2015), the Clean Environment Commission (CEC) attended 17 communities surrounding Lake Winnipeg.1 They also held two evening public sessions in Winnipeg and received a number of written submissions from the public.2 The CEC heard from many residents and users around the Lake including: cottage owners, permanent residents, Indigenous people, agricultural farmers, commercial and subsistence fishermen, and people and organizations from the tourism and recreation industry. There is disagreement in terms of the implications of Lake Winnipeg Regulation on Lake Winnipeg. Manitoba Hydro argues that its effects are generally either positive, benign or insignificant. Others take the position that LWR in conjunction with other Hydro activities has adverse and ongoing effect on the Lake. Among the prominent concerns are: • Lack of confidence in Manitoba Hydro, the Province and the CEC Hearing process on LWR • Lack of transparency of Manitoba Hydro and Manitoba Government operations of LWR • Lack of meaningful ongoing engagement • Sense of exclusion by upstream, downstream and Indigenous people • A sense that Manitoba hydro -

Exploring the Canoe in Canadian Experience, by James Raffan

318 • REVIEWS accounts, becomes a man who married for money and, when POWELL, T. 1961. The long rescue. London: W.H. Allen. it ran out, abandoned his wife to join the army. William Cross, TODD, A.L. 1961. Abandoned. New York: McGraw-Hill Book the alcoholic engineer who was the first to die, acquires Company. character through his gruff journal entries, usually colorful knocks at Greely, whom he labeled “Old Stubbornness” or Jerry Kobalenko “STN (our shirt-tail navigator)” (p. 157, 173). PO Box 1286 Guttridge’s fairness and the depth of his historical Banff, Alberta, Canada research are striking. If there is a drawback to Ghosts of T0L 0C0 Cape Sabine, it is that the 80-year-old author has no [email protected] personal experience with the Arctic he writes about and thus makes many small errors. Dutch Island lies within a few metres of mainland Ellesmere, not two miles offshore; BARK, SKIN, AND CEDAR: EXPLORING THE CA- the photo caption of Pim Island misidentifies Cape Sabine; NOE IN CANADIAN EXPERIENCE. By JAMES and contrary to what Greely himself believed, the small RAFFAN. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., 1999. seabirds the party hunted at Camp Clay were not dovekies: ISBN 0-00-638653-9. xiv + 274 p., maps, b&w illus., they were guillemots. More importantly, the author over- notes, index. Softbound. Cdn$19.95. looks key issues in the tragedy because of his lack of familiarity with the area. In February 1884, when Sergeant Bark, Skin, and Cedar will surely make for informative Rice and the Greenland native Jens Edward tried to cross and inspirational reading for housebound canoe enthusi- Smith Sound to reach Greenland for help, they were asts this year. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the