Atlantic Currents 2015 Iii Acronyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Political Ecology

Global Political Ecology The world is caught in the mesh of a series of environmental crises. So far attempts at resolving the deep basis of these have been superficial and disorganized. Global Political Ecology links the political economy of global capitalism with the political ecology of a series of environmental disasters and failed attempts at environmental policies. This critical volume draws together contributions from 25 leading intellectuals in the field. It begins with an introductory chapter that introduces the readers to political ecology and summarises the book’s main findings. The following seven sections cover topics on the political ecology of war and the disaster state; fuelling capitalism: energy scarcity and abundance; global governance of health, bodies, and genomics; the contradictions of global food; capital’s marginal product: effluents, waste, and garbage; water as a commodity, human right, and power; the functions and dysfunctions of the global green economy; political ecology of the global climate; and carbon emissions. This book contains accounts of the main currents of thought in each area that bring the topics completely up-to-date. The individual chapters contain a theoretical introduction linking in with the main themes of political ecology, as well as empirical information and case material. Global Political Ecology serves as a valuable reference for students interested in political ecology, environmental justice, and geography. Richard Peet holds degrees from the London School of Economics (BSc (Econ)), the University of British Columbia (MA), and the University of California, Berkeley (PhD). He is currently Professor of Geography at Clark University, Worcester, MA. His interests are development, global policy regimes, power, theory and philosophy, political ecology, and the causes of financial crises. -

UNA Mag July-Sep 2007.Qxp

NEWWORLD News and comment on the United Nations and UNA–UK On track or derailed? Progress towards the UN Millennium Development Goals PLUS: Justice not Vengeance It’s time to ditch the death penalty 2007 Review of UN Peace Operations Page 14 War and Democratic Accountability Page 20 UNITED NATIONS ASSOCIATION OF THE UK 3 Whitehall Court, London SW1A 2EL The UN Human Rights Council Page 22 www.una.org.uk Cartooning for Peace Page 35 £3.00 July–September 2007 Global Warming and the WI Page 38 UNA-UK CONTENTS Letter from the Executive Director 3 UNAUK Directory 4 UN: Miscellany 5 070707: the MDG Halfway Point 6 2007 Review of UN Peace Operations 14 UNAUK in Parliament 17 Annual Conference 2007 18 Waging War and Democratic Accountability 20 The UN Human Rights Council 22 It’s Time to Ditch the Death Penalty 26 The Oxford Handbook on the United Nations 29 Cartooning for Peace 35 UNA Westminster Pays Tribute to Peacekeepers 36 The Women’s Institute Tackles Waste 38 The Membership at Work 39 What’s On? 40 Books on the UN 41 Web Resources and Letters 42 Young Professionals Network 43 Newer World 46 MDGs Progress Chart 48 New World Subscription: is published by UNA-UK, 3 Whitehall Court, London SW1A 2EL Copies of New World are included in the membership fee for UNA-UK. www.una.org.uk Design: Advertisements: John Schwartz, [email protected] To advertise please call Veronica Lie on 020 7766 3451. The United Nations Association of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is ISSN: a company limited by guarantee (registered no. -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

Download Book

0111001001101011 01THE00101010100 0111001001101001 010PSYHOLOGY0111 011100OF01011100 010010010011010 0110011SILION011 01VALLEY01101001 ETHICAL THREATS AND EMOTIONAL UNINTELLIGENCE 01001001001110IN THE TECH INDUSTRY 10 0100100100KATY COOK 110110 0110011011100011 The Psychology of Silicon Valley “As someone who has studied the impact of technology since the early 1980s I am appalled at how psychological principles are being used as part of the busi- ness model of many tech companies. More and more often I see behaviorism at work in attempting to lure brains to a site or app and to keep them coming back day after day. This book exposes these practices and offers readers a glimpse behind the “emotional scenes” as tech companies come out psychologically fir- ing at their consumers. Unless these practices are exposed and made public, tech companies will continue to shape our brains and not in a good way.” —Larry D. Rosen, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, author of 7 books including The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High Tech World “The Psychology of Silicon Valley is a remarkable story of an industry’s shift from idealism to narcissism and even sociopathy. But deep cracks are showing in the Valley’s mantra of ‘we know better than you.’ Katy Cook’s engaging read has a message that needs to be heard now.” —Richard Freed, author of Wired Child “A welcome journey through the mind of the world’s most influential industry at a time when understanding Silicon Valley’s motivations, myths, and ethics are vitally important.” —Scott Galloway, Professor of Marketing, NYU and author of The Algebra of Happiness and The Four Katy Cook The Psychology of Silicon Valley Ethical Threats and Emotional Unintelligence in the Tech Industry Katy Cook Centre for Technology Awareness London, UK ISBN 978-3-030-27363-7 ISBN 978-3-030-27364-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27364-4 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 This book is an open access publication. -

Ending Well: a Longitudinal Evaluation of Everychild's

Ending well Phase 1 Interim report Longitudinal Evaluation of EveryChild’s Responsible Exit Process “Nothing in his life became him like the leaving it” Submitted by: Macbeth Act 1 Scene 4 Rick James Rowan Popplewell Jamie Bartlett March 2015 INTRAC Oxbridge Court, Osney Mead, Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Methods .............................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Limitations ........................................................................................................... 2 2 Overall exit situation in January 2015 .......................................................................... 3 2.1 Survey feedback from all countries ...................................................................... 3 2.2 Case studies ....................................................................................................... 3 2.3 The question of localising .................................................................................... 4 3 Exit process from 2012 onwards .................................................................................. 5 3.1 Who made the decision to exit -

Greed and Grievance in Civil War

# Oxford University Press 2004 Oxford Economic Papers 56 (2004), 563–595 563 All rights reserved doi:10.1093/oep/gpf064 Greed and grievance in civil war By Paul Collier* and Anke Hoefflery *Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford yCentre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford, 21 Winchester Road, Oxford OX2 6NA; e-mail: anke.hoeffl[email protected] We investigate the causes of civil war, using a new data set of wars during 1960–99. Rebellion may be explained by atypically severe grievances, such as high inequality, a lack of political rights, or ethnic and religious divisions in society. Alternatively, it might be explained by atypical opportunities for building a rebel organization. While it is difficult to find proxies for grievances and opportunities, we find that political and social variables that are most obviously related to grievances have little explanatory power. By contrast, economic variables, which could proxy some griev- ances but are perhaps more obviously related to the viability of rebellion, provide considerably more explanatory power. 1. Introduction Civil war is now far more common than international conflict: all of the 15 major armed conflicts listed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute for 2001 were internal (SIPRI, 2002). In this paper we develop an econometric model which predicts the outbreak of civil conflict. Analogous to the classic principles of murder detection, rebellion needs both motive and opportunity. The political science literature explains conflict in terms of motive: the circumstances in which people want to rebel are viewed as sufficiently rare to constitute the explanation. -

![Film Review: Red Dust [Univ. of Duisburg-Essen / Filmrezension.De]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8791/film-review-red-dust-univ-of-duisburg-essen-filmrezension-de-1088791.webp)

Film Review: Red Dust [Univ. of Duisburg-Essen / Filmrezension.De]

Benjamin Neumanni Benjamin Neumann Review of „Red Dust“ South Africa in Films University of Duisburg-Essen, Dr. Claudia Drawe pubished in cooperation with Düsseldorf 2007 Review of „Red Dust“ 1 Benjamin Neumanni Table of contents 1. Drum: Film review: More than telling Henry`s story 3 2. Film facts 12 3. references 13 Review of „Red Dust“ 2 Benjamin Neumanni Introduction: Red Dust (2004) South Africa some years after the end of apartheid. Three people are returning to the small dusty town of Smitsrivier. From New York comes South African- born lawyer Sarah Barcant (Hilary Swank), from a Cape Town prison former deputy-policeman Dirk Hendricks (Jamie Bartlett) and from the parliament politician Alex Mpondo (Chiwetel Ejiofor). And they all will face their own past... Red Dust first debuted on the cinema screens at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2004. The main theme of this festival was 'South Africa: Ten Years Later' . At the festival the new arising South African cinema was celebrated and also the tenth anniversary of the new South Africa after the end of apartheid. Ten South African made movies were shown to the audience. Three of these movies got a special screening. Thereby were Red Dust, the movie Yesterday (2004) and Hotel Rwanda (2004). Red Dust was receiving a stunning response by the audience at this festival. Was this response justified or not? Background: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission In 1995, one year after the end of the era of apartheid in South Africa, the Government of National Unity under president Nelson Mandela set up the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). -

A Journal of the Center for Complex Operations Vol. 4, No. 3

VOL. 4, NO. 3 2013 A JOURNA L O F THE CEN TER F OR C O MPL EX O PER ATIONS About PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, Vol. 4, no. 3 2013 and other partners on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; Editor and developments in training and education to transform America’s security Michael Miklaucic and development Associate Editors Mark D. Ducasse Stefano Santamato Communications Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Editorial Assistant communications to: Megan Cody Editor, PRISM Copy Editors 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Dale Erikson Fort Lesley J. McNair Sara Thannhauser Washington, DC 20319 Nathan White Telephone: (202) 685-3442 Advisory Board FAX: Dr. Gordon Adams (202) 685-3581 Dr. Pauline H. Baker Email: [email protected] Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Ambassador James F. Dobbins Contributions Ambassador John E. Herbst (ex officio) PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians Dr. David Kilcullen from the United States and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the Ambassador Jacques Paul Klein address above or by email to [email protected] with “Attention Submissions Dr. Roger B. Myerson Editor” in the subject line. Dr. Moisés Naím This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. MG William L. Nash, USA (Ret.) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador Thomas R. -

Assisting Africa to Achieve Decisive Change Paul Collier* Summary

SWEDISH ECONOMIC POLICY REVIEW 13 (2006) 169-197 Assisting Africa to achieve decisive change Paul Collier* Summary Africa has stagnated despite receiving considerable international aid. I suggest that the most reasonable counterfactual is that without aid Africa would have declined, so that aid has been helpful in averting disaster, although lacking the power to achieve decisive change. Based on a diagnosis of the reasons for past stagnation, I propose five un- exploited opportunities for aid better to complement internal African efforts at transformation. JEL classification: O11, O19, O55. Key words: Aid, Africa, Growth, Governance. * Paul Collier is Professor of Economics at the Centre for the Study of African Economies at Oxford University. 169 SWEDISH ECONOMIC POLICY REVIEW 13 (2006) 169-197 Assisting Africa to achieve decisive change Paul Collier* Africa is the only substantial low-income part of the world that has persistently failed to grow. Over the period 1960-2000 the popula- tion-weighted grow rate of per capita income averaged a mere 0.13 per cent. It thus appears likely that Africa is the development chal- lenge of the future. This paper asks what will it take to achieve a deci- sive break with this past record, and in particular, what is the role of external actors in assisting this change? The times may be propitious for such change. Since around 2000 African economic performance has improved. This may reflect im- portant fundamental changes that will make the future different from the past. Even if, on a less optimistic interpretation, the recent im- provement simply reflects the temporary boom in commodity prices, African societies may have learnt from past mistakes and use these windfalls as the launch pad to prosperity. -

POEC 301 Syllabus

Jon Bakija Jim Mahon Schapiro 330 Schapiro 226 office: x2325 office: x2236 Office hours: Office hours: Tu 1:30-3:30 W, F 10:30-noon and by app’t. and by app’t [email protected] [email protected] POLITICAL ECONOMY 250 ECONOMIC LIBERALISM AND ITS CRITICS Fall 2012 This course explores the relationship between politics and economics by surveying influential works of political economy. Its first part examines major systems of thought in relation to the historical development of capitalism in Britain and the United States, from the classical liberalism of Adam Smith to the works of John Maynard Keynes. The second part considers more recent writings, with more of a focus on policy issues and the USA. The historical nature of the course permits you to appreciate the ongoing dialogue between classical and contemporary views of political economy. The Political Economy major at Williams aims to prepare students for active engagement in public life. This course has two purposes in relation to the major: first, to expose you to the intellectual roots of the political- economic theories you will encounter in your senior courses; and second, to provide a space for you to reflect about the ethical issues that arise whenever one seeks not only to analyze public policy, but to make it. This syllabus is the single most important document for the course. It has been annotated with some information about the authors and the themes of their work, in order to contextualize your reading and leave more class time for discussion of ideas. It also includes study questions. -

The Relationship Between Influential Actors' Language and Violence: A

FEBRUARY 2019 The relationship between influential actors’ language and violence: A Kenyan case study using artificial intelligence Chris Mahony Eduardo Albrecht Murat Sensoy Abstract Scholarly work addressing the drivers of violent conflict predominantly focus on macro-level factors, often surrounding social group-specific grievances relating to access to power, justice, security, services, land, and resources. Recent work identifies these factors of risk and their heightened risk during shocks, such as a natural disaster or significant economic adjustment. What we know little about is the role played by influential actors in mobilising people towards or away from violence during such episodes. We hypothesise that influential actors’ language indicates their intent towards or away from violence. Much work has been done to identify what constitutes hostile vernacular in political systems prone to violence, however, it has not considered the language of specific influential actors. Our methodology targeting this knowledge gap employs a suite of third party software tools to collect and analyse 6,100 Kenyan social media (Twitter) utterances from January 2012 to December 2017. This software reads and understands words’ meaning in multiple languages to allocate sentiment scores using a technology called Natural Language Processing (NLP). The proprietary NLP software, which incorporates the latest artificial intelligence advances, including deep learning, transforms unstructured textual data (i.e. a tweet or blog post) into structured data (i.e. a number) to gauge the authors’ changing emotional tone over time. Our model predicts both increases and decreases in average fatalities 50 to 150 days in advance, with overall accuracy approaching 85%. This finding suggests a role for influential actors in determining increases or decreases in violence and the method’s potential for advancing understandings of violence and language. -

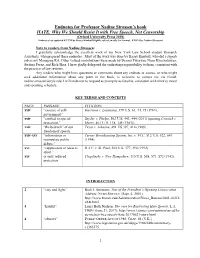

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen's Book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen’s book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship (Oxford University Press 2018) Endnotes last updated 4/27/18 by Kasey Kimball (lightly edited, mostly for format, 4/28/18 by Nadine Strossen) Note to readers from Nadine Strossen: I gratefully acknowledge the excellent work of my New York Law School student Research Assistants, who prepared these endnotes. Most of the work was done by Kasey Kimball, who did a superb job as my Managing RA. Other valued contributions were made by Dennis Futoryan, Nana Khachaturyan, Stefano Perez, and Rick Shea. I have gladly delegated the endnoting responsibility to them, consistent with the practice of law reviews. Any readers who might have questions or comments about any endnote or source, or who might seek additional information about any point in the book, is welcome to contact me via Email: [email protected]. I will endeavor to respond as promptly as feasible, consistent with a heavy travel and speaking schedule. KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS PAGE PASSAGE CITATION xxiv “essence of self- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74, 75 (1964). government.” xxiv “entitled to special Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. protection.” Myers, 461 U. S. 138, 145 (1983)). xxiv “the bedrock” of our Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397, 414 (1989). freedom of speech. xxiv-xxv “information or Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 641 manipulate public (1994). debate.” xxv “suppression of ideas is R.A.V. v. St.