Coming Around:The Urban Ring and the Future of Transit in Greater Boston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umass Boston Community Guide

UMass Boston Community Guide _________________________________________________ OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING _________________________________________________ 100 Morrissey Boulevard Boston, MA 02125-3393 OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING P: 617.287.6011 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON F: 617.287.6335 E: [email protected] www.umb.edu/housing CONTENTS Boston Area Communities 3 Dorchester 3 Quincy 4 Mattapan 5 Braintree 6 South Boston 7 Cambridge 8 Somerville 9 East Boston 10 Transportation 11 MBTA 11 Driving 12 Biking 12 Trash Collection & Recycling 13 Being a Good Neighbor 14 Engage in Your Community 16 Volunteer 16 Register to Vote 16 Community Guide | Pg 2 100 Morrissey Boulevard Boston, MA 02125-3393 OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING P: 617.287.6011 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON F: 617.287.6335 E: [email protected] www.umb.edu/housing BOSTON AREA COMMUNITIES Not sure what neighborhood to live in? This guide will introduce you to neighborhoods along the red line (the ‘T’ line that serves UMass Boston), as well as affordable neighborhoods where students tend to live. Visit these resources for more information on neighborhoods and rental costs in Boston: Jumpshell Neighborhoods City of Boston Neighborhood Guide Rental Cost Map Average Rent in Boston Infographic Dorchester: Andrew – JFK/UMass – Savin Hill – Fields Corner – Shawmut, Ashmont, Ashmont-Mattapan High Speed Line Dorchester is Boston’s largest and oldest neighborhood, and is home to UMass Boston. Dorchester's demographic diversity has been a well-sustained tradition of the neighborhood, and long-time residents blend with more recent immigrants. A number of smaller communities compose the greater neighborhood, including Codman Square, Jones Hill, Meeting House Hill, Pope's Hill, Savin Hill, Harbor Point, and Lower Mills. -

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT The 2003 PMT outlined the actions needed to bring the MBTA transit system into a state of good repair (SGR). It evaluated and prioritized a number of specific enhancement and expansion projects proposed to improve the system and better serve the regional mobility needs of Commonwealth residents. In the inter- vening years, the MBTA has funded and implemented many of the 2003 PMT priorities. The transit improvements highlighted in this chapter have been accomplished in spite of the unsus- tainable condition of the Authority’s present financial structure. A 2009 report issued by the MBTA Advisory Board1 effectively summarized the Authority’s financial dilemma: For the past several years the MBTA has only balanced its budgets by restructuring debt liquidat- ing cash reserves, selling land, and other one-time actions. Today, with credit markets frozen, cash reserves depleted and the real estate market at a stand still, the MBTA has used up these options. This recession has laid bare the fact that the MBTA is mired in a structural, on-going deficit that threatens its viability. In 2000 the MBTA was re-born with the passage of the Forward Funding legislation.This legislation dedicated 20% of all sales taxes collected state-wide to the MBTA. It also transferred over $3.3 billion in Commonwealth debt from the State’s books to the T’s books. In essence, the MBTA was born broke. Throughout the 1990’s the Massachusetts sales tax grew at an average of 6.5% per year. This decade the sales tax has barely averaged 1% annual growth. -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

MBTA Green Line Extension (GLX) Project Community Working Group (CWG) Meeting Minutes February 2, 2021 8:30 to 10:00 AM Via Webinar

MBTA Green Line Extension (GLX) Project Community Working Group (CWG) Meeting Minutes February 2, 2021 8:30 to 10:00 AM Via Webinar *This meeting is the 39th consecutive, monthly GLX Community Working Group meeting. ATTENDEES: Elected Officials: Representative Christine Barber CWG Members (in alphabetical order): Ryan Dunn (Co-Chair) Viola Augustin (Somerville) Joseph Barr (City of Cambridge) Elliot Bradshaw (Brickbottom) Rocco Dirico (Tufts University) Jim McGinnis (Union Square) Andrew Reker (City of Cambridge) Laurel Ruma (Medford – College Ave) Jim Silva (Medford - Ball Square) Michaela Bogosh MassDOT/MBTA: Melissa Dullea (Senior Director MBTA Service and Planning) Terry McCarthy (MBTA Deputy Program Manager of Stakeholder Engagement) Marggie Lackner (MBTA Deputy Chief, QA/QC) GLX Project Team: Martin Nee (GLX-Consultant) Erin Reed (GLXC) Jeff Wagner (GLXC) Matt Davy (GLX-Consultant) Richard Monahan (GLX-MBTA) Other Guests: Tim Dineen (VNA Resident) Karen Breslawski Gregory Jenkins PURPOSE: The GLX Community Working Group (CWG) was formed to help engage and foster communication with the communities along the GLX corridor by meeting with representative members (both residents and officials) of Cambridge, Somerville, and Medford. BACKGROUND: The Green Line Extension (GLX) Project is an initiative of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), in coordination with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA). The project intent is to extend existing MBTA Green Line service from Lechmere Station Page 1 through the northwest corridor communities of Cambridge, Somerville, and Medford. The goals of the project are to increase mobility; encourage public transit usage; improve regional air quality; ensure a more equitable distribution of transit services; and support opportunities for sustainable development. -

Draft TIP Transit Programming MBTA Project

MBTA Federal Capital Program ‐ FTA Formula Funds FFY 2018‐2023 TIP Project Descriptions ‐ Provided for Informational Purposes For Presentation to the Boston MPO on 3/22/2018 TIP Project Name Project Description 5307 ‐ Revenue Vehicle Program Commuter Rail Locomotive Reliability This program will restore coaches and locomotives, beyond their useful life, to a state of Program good repair to support service and winter resilliency efforts Procurement of 60‐foot Dual Mode Articulated (DMA) buses to replace the existing fleet of DMA Bus Replacement 32 Silver Line Bus Rapid Transit buses and to provide for ridership expansion projected as a result of Silver Line service extension to Chelsea. Green Line Light Rail Fleet Replacement ‐ Development of technical specifications for the procurement of light rail vehicles to replace Design the existing fleet that is approaching the end of its service life. Overhaul of locomotives in operation on commuter rail lines systemwide in order to improve Locomotive Overhaul reliability. Replacement of major systems and refurbishment of seating and other customer facing MBTA Catamaran Overhaul components on two catamarans (Lightning and Flying Cloud). Midlife Overhaul of 25 New Flyer Allison Overhaul of 25 hybrid buses, brought into service in 2009 and 2010, to enable optimal Hybrid 60 ft Articulated Buses reliability through the end of their service life. Overhaul of 32 Neoplan 60' DMA Buses Overhaul of the Neoplan 60' Dual Mode Articulated buses that operate on the MBTA Silver (5307) Line Bus Rapid Transit routes. Overhaul of 33 Kawasaki 900 Series Bi‐Level Overhaul and upgrade of existing systems on commuter rail coaches that were brought into Coaches service in 2005 to enable optimal reliability through the end of their service life. -

Sustainable Commuting

Employee Commuter MBTA Discounts Benefit Programs Tufts is a member of A Better City Faculty & Staff Sustainable Transportation Management Association Boston employees receive a 35% discount on bus, train, or (ABC TMA), which provides incentives and commuter rail MBTA passes (up to $50 per month). Save cash programs for encouraging people to commute sustainably. by using pre-tax money to buy your train, bus, and subway For more information or to sign up for any ABC TMA tickets and/or your vanpool or commuter parking. For more Commuting programs, visit abctma.com. details, visit go.tufts.edu/commuterbenefits. RideAmigos Students go.tufts.edu/mbtadiscount RideAmigos has partnered with ABC TMA to provide Boston-based, full-time students in Tufts Health Science commuter benefits to those who switch to sustainable School programs can purchase an MBTA Semester Pass at a Boston Campus commuting options. Use the RideAmigos app to log 35% discount. the miles you sustainably commute! Recording your 1. Log into SIS: sis.tufts.edu environmentally friendly commute can win you monthly 2. Navigate to the “Bills & Balances” tab raffles, gift cards, gear, and more. These benefits are only 3. Click “Purchase MBTA Pass” available to Tufts employees. To register for RideAmigos Order Fall passes by Aug. 8th and Spring passes by Dec. 8th. vist abctma.com/members/. Once on the RideAmigos Each student is entitled to one pass. website you can record your sustainable commute. All the subsidies are listed as rewards in the RideAmigos app and Transit Tip: you will only be eligible to get them if you are tracking your Use a Charlie Card to avoid a sustainable commutes. -

Directions to Boston - Local Parking

Directions to Boston - Local Parking GENERAL INFORMATION Logan Express (Recommended) The Back Bay Logan Express runs from all airport terminals directly to St. James Street in Copley Square in Back Bay diagonally across the street from the hotel. Departures occur at :00, :20, and :40 from 5am to 9pm daily. Fares are $7.50 per passenger – payment is by Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners Club (NO CASH). All buses are wheelchair accessible. Subway The closest subway stations are Copley Station (on the Green Line) and Back Bay Station (on the Orange Line). Both stations are within 1 block of the hotel. The MBTA runs daily from 6:00 AM to 1:00 AM. The schedule varies based on line, day of week, and reliability of the service. The cost is $2.75 per ride. Cab Transportation Green transportation is available through Lifestyle Transportation International (LTI) and Boston Cabs. Both transportation companies offer hybrid and Flex-Fuel vehicles in their fleet. Taxi fares from the airport to the hotel range from $40-50. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION From Airport via Subway From airport terminal take a MassPort shuttle bus to the Airport subway station. Take the inbound Blue Line train to Government Center. Then, transfer to any outbound Green Line train to go to Copley station. Make a right onto Dartmouth Street - the hotel is 300 feet down the block on the same side of the street. The fare is $2.75. OR From airport terminal take any Silver Line bus to South Station. Change to an “Alewife” bound Red Line to Park Street. -

MIT Kendall Square

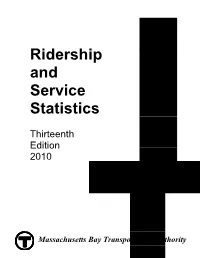

Ridership and Service Statistics Thirteenth Edition 2010 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile July 2010 MBTA Service District Cities and Towns 175 Size in Square Miles 3,244 Population (2000 Census) 4,663,565 Typical Weekday Ridership (FY 2010) By Line Unlinked Red Line 241,603 Orange Line 184,961 Blue Line 57,273 Total Heavy Rail 483,837 Total Green Line (Light Rail & Trolley) 236,096 Bus (includes Silver Line) 361,676 Silver Line SL1 & SL2* 14,940 Silver Line SL4 & SL5** 15,086 Trackless Trolley 12,364 Total Bus and Trackless Trolley 374,040 TOTAL MBTA-Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 System Unlinked MBTA - Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 Commuter Rail Boardings (Inbound + Outbound) 132,720 Contracted Bus 2,603 Water Transportation 4,372 THE RIDE Paratransit Trips Delivered 6,773 TOTAL ALL MODES UNLINKED 1,240,441 Notes: Unlinked trips are the number of passengers who board public transportation vehicles. Passengers are counted each time they board vehicles no matter how many vehicles they use to travel from their origin to their destination. * Average weekday ridership taken from 2009 CTPS surveys for Silver Line SL1 & SL2. ** SL4 service began in October 2009. Ridership represents a partial year of operation. File: CH 01 p02-7 - MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile Jul10 1 Annual Ridership (FY 2010) Unlinked Trips by Mode Heavy Rail - Red Line 74,445,042 Total Heavy Rail - Orange Line 54,596,634 Heavy Rail Heavy Rail - Blue Line 17,876,009 146,917,685 Light Rail (includes Mattapan-Ashmont Trolley) 75,916,005 Bus (includes Silver Line) 108,088,300 Total Rubber Tire Trackless Trolley 3,438,160 111,526,460 TOTAL Subway & Bus/Trackless Trolley 334,360,150 Commuter Rail 36,930,089 THE RIDE Paratransit 2,095,932 Ferry (ex. -

Page 1 of 8 PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Emai

PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Email: [email protected] RESUME Summary Phil Craig has 50 years of experience in the rail transit and railroad field. My expertise is in planning, design, construction, and operation of heavy rail rapid transit systems (metros or subways), light rail transit systems, suburban or regional (commuter) rail systems, high-speed passenger railways, and main line passenger and freight railroads. My broad technical knowledge as a transportation planner and analyst encompasses a wide range of planning, operations, and management areas. I have held significant management positions with transport organizations serving large metropolitan areas in the United States, Great Britain and Greece, as well having been a consultant on rail projects in Canada, India, South Korea, Taiwan and Turkey. Education Bachelor of Science (Cum Laude), Public Utilities and Transportation, New York University, New York, New York, 1963 Professional Data Past Chairman (1973-76) and Committee Member (1972-80), Subcommittee on Federal Rules and Regulations Committee on Mobility for the Elderly and Handicapped American Public Transit Association, Washington, D.C., USA Member, Light Rail Transit Association, London, England Member, Light Rail Panel, New Jersey Association of Railroad Passengers Experience Independent Transportation Consultant – March 2009 to July 2009 Project: Honolulu High Capacity Transit Corridor Project, Honolulu, O'ahu, Hawai'i Clients: Kamehameha Schools and Honolulu Chapter of American Institute of Architects Assignment: Analyze Potential for Use of Light Rail Transit Technology Roles: Consultant to Kamehameha Schools and Adviser to AIA Honolulu Prepared a Light Rail Transit Feasibility Report for Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate (the largest private landholder in the Hawaiian Islands). -

A National Colloquium May 3 -4, 2012, Boston, MA

Arresting Demand: A National Colloquium May 3 -4, 2012, Boston, MA Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is the location of the colloquium? We are hosting the colloquium at the Westin Copley Place, located at 10 Huntington, Avenue Boston, MA 02116. Please visit their website at www.westin.com/Boston. 2. I have already registered but cannot attend. Can I cancel or transfer my registration? Yes, you may transfer your registration to a colleague in order to take your place at the conference. However, you will be responsible for any fees related to changes made to your travel arrangements. 3. Can I invite a guest to the conference? If you would like to invite a guest or suggest a colleague that should be added to our list please contact Alyssa Ozimek-Maier. 4. When is the registration deadline? Friday, April 6, is the registration deadline for the colloquium. If there is a circumstance that will prevent you from completing your registration by that time please contact Alyssa Ozimek-Maier. 5. What meals will be provided during the conference? All meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) will be provided during the two day colloquium. Please be sure to notify us of any dietary preferences, via registration and we will work diligently to make sure that each request is respected. 6. I have questions about my travel arrangements. Who should I contact? Any questions regarding your personal travel arrangements should be directed to Travel Collaborative at [email protected]. 7. Will parking be available? Parking at the hotel will be available through valet service only courtesy of Hunt Alternatives Fund. -

May 22, 2017 Volume 37

MAY 22, 2017 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 37 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 5 A Club in Transition 3 The Semaphore David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Cape Cod News………………………………….Skip Burton Boston Globe Reporter………………………. Brendan Sheehan Boston Herald Reporter……………………… Jim South Wall Street Journal Reporter....………………. Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli Empire State News…………………………… Dick Kozlowski Amtrak News……………………………. .. Rick Sutton, Russell Buck “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart PRODUCTION STAFF Publication………………………………… ….. Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Web Page …………………..…………………… Savery Moore Club Photographer……………………………….Joe Dumas The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2017 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 37 ■■■■■ NUMBER 5 ■■■■■ MAY 2017 CLUB OFFICERS BILL OF LADING President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Chief’s Corner ...... …….….4 Treasurer………………....Will Baker A Club in Transition….…..13 Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Contests ................ ………..4 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’18) Clinic……………..….…….7 ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘18) ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’17) Editor’s Notes. ….…....… .13 …………………………...Rick Sutton (‘17) Form 19 Orders .... ………..4 Members .............. ….…....14 Memories ............. .………..5 Potpourri .............. ..……….7 ON THE COVER: The first 25% of our building was Running Extra ..... -

Culturalism Through Public Art Practices

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2011 Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices Anru Lee CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice Perng-juh Peter Shyong How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/49 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 How to Cite: Lee, Anru, and Perng-juh Peter Shyong. 2011. “Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices.” In Tak-Wing Ngo and Hong-zen Wang (eds.) Politics of Difference in Taiwan. Pp. 181-207. London and New York: Routledge. 2 Assessing (Multi)culturalism through Public Art Practices Anru Lee and Perng-juh Peter Shyong This chapter investigates the issue of multiculturalism through public art practices in Taiwan. Specifically, we focus on the public art project of the Mass 14Rapid Transit System in Kaohsiung (hereafter, Kaohsiung MRT), and examine how the discourse of multiculturalism intertwines with the discourse of public art that informs the practice of the latter. Multiculturalism in this case is considered as an ideological embodiment of the politics of difference, wherein our main concern is placed on the ways in which different constituencies in Kaohsiung respond to the political-economic ordering of Kaohsiung in post-Second World War Taiwan and to the challenges Kaohsiung City faces in the recent events engendering global economic change. We see the Kaohsiung MRT public art project as a field of contentions and its public artwork as a ‘device of imagination’ and ‘technique of representation’ (see Ngo and Wang in this volume).