Elevating Chardonnay in the Santa Cruz Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

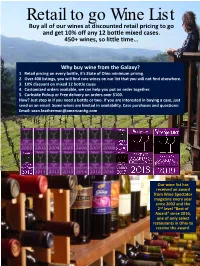

Retail to Go Wine List Buy All of Our Wines at Discounted Retail Pricing to Go and Get 10% Off Any 12 Bottle Mixed Cases

Retail to go Wine List Buy all of our wines at discounted retail pricing to go and get 10% off any 12 bottle mixed cases. 450+ wines, so little time… Why buy wine from the Galaxy? 1. Retail pricing on every bottle, it's State of Ohio minimum pricing. 2. Over 400 listings, you will find rare wines on our list that you will not find elsewhere. 3. 10% discount on mixed 12 bottle cases 4. Customized orders available, we can help you put an order together. 5. Curbside Pickup or Free delivery on orders over $100. How? Just stop in if you need a bottle or two. If you are interested in buying a case, just send us an email. Some wines are limited in availability. Case purchases and questions: Email: [email protected] Our wine list has received an award from Wine Spectator magazine every year since 2002 and the 2nd level “Best of Award” since 2016, one of only select restaurants in Ohio to receive the award. White Chardonnay 76 Galaxy Chardonnay $12 California 87 Toasted Head Chardonnay $14 2017 California 269 Debonne Reserve Chardonnay $15 2017 Grand River Valley, Ohio 279 Kendall Jackson Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay $15 2018 California 126 Alexander Valley Vineyards Chardonnay $15 2018 Alexander Valley AVA,California 246 Diora Chardonnay $15 2018 Central Coast, Monterey AVA, California 88 Wente Morning Fog Chardonnay $16 2017 Livermore Valley AVA, California 256 Domain Naturalist Chardonnay $16 2016 Margaret River, Australia 242 La Crema Chardonnay $20 2018 Sonoma Coast AVA, California (WS89 - Best from 2020-2024) 241 Lioco Sonoma -

Old Vine Field Blends in California: a Review of Late 19Th Century Planting Practices in Californian Vineyards and Their Relevance to Today’S Viticulture

Old Vine Field Blends in California: A review of late 19th century planting practices in Californian vineyards and their relevance to today’s viticulture. A research paper based upon Bedrock Vineyard, planted in 1888. © The Institute of Masters of Wine 2017. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission. This publication was produced for private purpose and its accuracy and completeness is not guaranteed by the Institute. It is not intended to be relied on by third parties and the Institute accepts no liability in relation to its use. Table of Contents 1. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Situational Context.......................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Written Works on California Field Blends ............................................................... 4 3.2 International Use of Field-Blending ......................................................................... 4 3.3 Known Benefits of Co-fermentation ......................................................................... 6 4. Methodology ................................................................................................................... 8 4.1. Historic Primary Document Research .................................................................... -

After 47 Years, Paul Draper Retires Fall 2016

Fall 2016 After 47 Years, Paul Draper Retires Dave Bennion, Charlie Rosen, and Hew Crane, the three scientists from Stanford Research Institute (SRI) 80 years – It seems a most celebratory age to step who had reopened the old Monte Bello Winery as Ridge back. We have two of the finest winemakers and one Vineyards in 1962 had heard me speak about Chile and of the most exceptional vineyard directors, who have our traditional methods. What I described fit with what each been with me for more than twenty years. Though they were doing and their idea that wine was something I have done all major tasting with Eric Baugher, John “real” and a perfect corrective to the “virtual” world that Olney and David Gates, the wines of the last ten years they were pioneering in their work at SRI. In offering are theirs, not mine, so you already know the quality me the job of winemaker they had me taste the ’62 and style of the vintages to come. and ’64 Monte Bellos made from cabernet replanted in the 1940’s at Monte Bello. They had never made wine I grew up on an eighty-acre farm west of Chicago. After before and had simply picked the grapes on a Saturday, attending the Choate School and receiving a degree in crushed them to a small fermentor adding no yeast philosophy from Stanford University, I lived for two and a and went back to their jobs. They had placed a grid to half years in northern Italy, putting in the military service submerge the grapes and came back the next weekend still required by the draft. -

J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast

Gold Wine Club Vol 28i12 P TheMedal WinningWine Wines from California’s Best Family-Ownedress Wineries. J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast Gold Medal Wine Club The Best Wine Club on the Planet. Period. J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red” Blend Paso Robles Highlands District, California 1,000 Cases Produced The J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red” is a blend of 90% Barbera and 10% Lagrein from the renowned Paso Robles Highlands District on California’s Central Coast. This District, which is the most southeast sub appellation within the Paso Robles AVA, is an absolutely fantastic place to grow wine grapes, partly due to its average 55 degree temperature swing from day to night (the highest diurnal temperature swing in the United States!), and also in part to its combination of sandy and clay soils that promote very vigorous vines. The high temperature swing, by the way, crafting bold, complex red blends like the J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red.” This wine opens with incredibly seductive slows the ripening rate of the fruit on the vine and allows flavors to develop, which is especially important when and just the right balance of bright, deep, and elegant nuances. Suggested food pairings for the J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’saromas Red”of blackberry, include barbecued huckleberry, steak, and pork, freshly or beefberry stew. pie. AgedThe palate in oak. is Enjoy dry, but now very until fruity 2027. with dark berry flavors Gold Medal Special Selection J. Wilkes 2016 Chardonnay Paso Robles Highlands District, California 1,000 Cases Produced J. Wilkes’ 2016 Chardonnay also comes from the esteemed Paso Robles Highlands District, a region that may be dominated by red wine grapes, but the Chardonnay grown here is well-respected and offers some 2016 Chardonnay opens with dominating aromas of ripe pear, green apple and lime zest. -

Sran Family Farms Is a Private Family Owned Agriculture Business That Specializes in the Farming of Almonds, Pistachios, and Vineyards

Single Tenant Net Leased Investment 20-Year Vineyard Land Lease Arroyo Road | Livermore, CA 94550 Contents Property Information Quinn Mulrooney Xavier Santana 3 Director | Agriculture Services CEO 209 733 9415 925 226 2455 [email protected] [email protected] 4 About Tenant Lic. # 02097075 Lic. # 01317296 Aaron Liljenquist Jon Kendall VP | Agriculture Properties Associate | Agriculture 5 Lease Abstract 209 253 7626 209 485 9989 [email protected] [email protected] Lic. # 02092084 Lic. # 02023907 6 Parcel Map ® 2020 Northgate Commercial Real Estate. We obtained the information above from sources we believe to 8 About City be reliable. However, we have not verified its accuracy and make guarantee, warranty or representation about it. It is submitted subject to the possibility of errors, omissions, change of price, rental or other conditions, prior sale, lease or financing, or withdrawal without notice. We include projections, opinions, assumptions or estimates for example only, and they may not represent current or future performance of the property. You and your tax and legal advisors should conduct your own investigation of the property and 9 Demographics transaction. Arroyo Road | Livermore, California 2 Property Information Sales Price: $2,200,000 Cap Rate: 5% APN: 99-682-6 Term: 20 year Zoning: Use Code 5500 Rural Agriculture 10+ NOI: $110,000 acres Options: Four(4) options 5-Years Water Source: Zone 7 Water Agency Parcel Size: ±50 Acres Williamson Act: Yes • Large consumer base with an estimated population of 92,886 people and a high average household income of $176,081 within a 5-mile radius • City offers a surplus of dining, lodging, shopping, outdoor activities, 50+ wineries, and organized tour options for visitors. -

SYRAH May 15, 2017 with Special Expert Host Jeb Dunnuck, Wine Advocate Reviewer

Colorado Cultivar Camp: SYRAH May 15, 2017 With special expert host Jeb Dunnuck, Wine Advocate Reviewer COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Colorado Wine Industry Development Board Agenda • All about Syrah • History • Geography • Biology • Masterclass tasting – led by Jeb Dunnuck • Rhone, California, Washington, Australia • Blind comparison tasting • Colorado vs. The World COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Colorado Wine Industry Development Board Jancis Robinson’s Wine Course By Jancis Robinson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0r1gpZ0e84k All About Syrah • History • Origin • Parentage • Related varieties • Geography • France • Australia • USA • Biology • Characteristics • Flavors COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Colorado Wine Industry Development Board History of Syrah • Myth suggests it was brought from Shiraz, Iran to Marseille by Phocaeans. • Or name came from Syracuse, Italy (on island of Sicily) • Widely planted in Northern Rhône • Used as a blending grape in Southern Rhône • Called Shiraz (sometimes Hermitage) in Australia • second largest planting of Syrah • Brought to Australia in 1831 by James Busby • Most popular cultivar in Australia by 1860 • Export to US in 1970s • Seventh most planted cultivar worldwide now, but only 3,300 acres in 1958 COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Colorado Wine Industry Development Board History of Syrah • Parentage: • Dureza • Exclusively planted in Rhône • In 1988, only one hectare remained • Mondeuse blanche • Savoie region of France • Only 5 hectares remain • Not to be confused with Petite Sirah -

2010 EBGB Chardonnayproduct-Pdf

2010 EBGB Chardonnayproduct-pdf - North Coast *Ultimate 'Go-To' White Why We're Drinking It California’s North Coast covers more than 3 million acres, so you’d think finding a great high-value North Coast Chardonnay would be an easy task. The reality is, it’s not – unless, like a few members of our Sourcing Team, you’re lucky enough to know the wines of Pat Paulsen (the pioneer of the well-respected "celebrity-owned" wineries) and, more specifically, their EBGB wine series. “Good Chardonnay at a great price,” it's all fresh apple and pear, touched with a bit of oak and a juicy mouthfeel; all to make for a party wine that's heads and shoulders above its single-digit peers. From Pat Paulsen Vineyards, (who garnered tremendous praise and a wide following as one of the first successful and well-respected "celebrity-owned" wineries), this is EBGB. The (literal) underground EBGB wine bar originally conceived by Montgomery Paulsen to compliment Paulsen Vineyards, the winery’s Chardonnay encompasses the “go-to” hot spot. Grown in choice vineyards across the North Coast, the fruit (and flavors) mingle together like the artists that frequent the wine bar. One of the more creatively-named wines of Paulsen Vineyards (among American Gothic Red, Whirligig, and Paulsen for President), “EBGB” is everything Pat Paulsen desired for his 1980s creation: wines with personality, flair, and a little satire. Inside Fact: A rough-edged rectangle, the North Coast AVA measures 120 miles (195km) from north to south, and half that from east to west. -

Lamorinda AVA Petition

PETITION TO ESTABLISH A NEW AMERICAN VITICULTURAL AREA TO BE NAMED LAMORINDA The following petition serves as a formal request for the establishment and recognition of an American Viticultural Area to be named Lamorinda, located in Contra Costa County, California. The proposed AVA covers 29,369 acres and includes nearly 139 acres of planted vines and planned plantings. Approximately 85% of this acreage is occupied or will be occupied by commercial viticulture (46 growers). There are six bonded wineries in the proposed AVA and three additional growers are planning bonded wineries. The large number of growers and relatively limited acreage demonstrates an area characterized by small vineyards, a result of some of the unique characteristics of the area. This petition is being submitted by Patrick L. Shabram on behalf of Lamorinda Wine Growers Association. Wineries and growers that are members of the Lamorinda Wine Growers Association are listed in Exhibit M: Lamorinda Wine Growers Association. This petition contains all the information required to establish an AVA in accordance with Title 27 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 9.3. List of unique characteristics: All viticulture limited to moderate-to-moderately steep slopes carved from of uplifted sedimentary rock. Geological rock is younger, less resistant sedimentary rock than neighboring rock. Other surrounding areas are areas of active deposition. Soils in Lamorinda have higher clay content, a result of weathered claystone. The topography allows for shallow soils and good runoff, reducing moisture held in the soil. Despite its position near intrusions of coastal air, Lamorinda is protected from coastal cooling influences. Daytime microclimates are more dependent on slope, orientation, and exposure, leading to a large number of microclimates. -

(SLO Coast) Viticultural Area

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 191 / Thursday, October 1, 2020 / Proposed Rules 61899 (3) Proceed along the Charles City DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Background on Viticultural Areas County boundary, crossing onto the TTB Authority Petersburg, Virginia, map and Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade continuing along the Charles City Bureau Section 105(e) of the Federal Alcohol County boundary to the point where it Administration Act (FAA Act), 27 intersects the Henrico County boundary 27 CFR Part 9 U.S.C. 205(e), authorizes the Secretary at Turkey Island Creek; then of the Treasury to prescribe regulations for the labeling of wine, distilled spirits, (4) Proceed north-northeasterly along [Docket No. TTB–2020–0009; Notice No. 194] and malt beverages. The FAA Act the concurrent Henrico County–Charles provides that these regulations should, City County boundary to its intersection among other things, prohibit consumer RIN 1513–AC59 with the Chickahominy River, which is deception and the use of misleading concurrent with the New Kent County Proposed Establishment of the San statements on labels, and ensure that boundary; then Luis Obispo Coast (SLO Coast) labels provide the consumer with (5) Proceed northwesterly along the Viticultural Area adequate information as to the identity Chickahominy River–New Kent County and quality of the product. The Alcohol boundary, crossing onto the Richmond, AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Virginia, map to its intersection with the Trade Bureau, Treasury. (TTB) administers the FAA Act Hanover County boundary; then pursuant to section 1111(d) of the ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. -

2018 Maggie's Vineyard Zinfandel

2018 Maggie’s Vineyard Zinfandel Reserve 92 Points – Wine Spectator, April 2020 2018 Kent’s Legacy Heritage Blend 92 Points – Wine Spectator, February 2020 2017 Alegria Zinfandel 93 Points – Wine Enthusiast, April 2019 2017 Mama’s Reserve 93 Points – Wine Enthusiast, April 2019 2017 Monte Rosso Zinfandel 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, April 2019 2017 St Peter’s Church Zinfandel 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, April 2019 2017 Albarino Gold/93 Points – 2018 International Women’s Wine Competition 2017 Ciliegiolo Best of Class/Silver/91 Points – 2018 California State Fair 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon, Rigg Vineyard 91 Points – Wine Enthusiast, April 2019 2016 Chardonnay, Santa Lucia Highlands 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, April 2019 2016 Alegria Zinfandel 92 Points – Wine Enthusiast, September 2018 2016 Alverd 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, December 2017 2016 Cuvee Exceptionnelle Zinfandel Best of Class/Gold/95 Points – 2018 California State Fair 2016 Diego’s Reserve Carmenere 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, September 2018 2016 Dry Creek Zinfandel 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, September 2018 2016 Estate Pinot Noir Double Gold – 2018 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition Gold/92 Points – 2018 International Women’s Wine Competition 2016 Fiano 90 Points – Wine Enthusiast, February 2018 2016 Hendry Vineyard Zinfandel 90 Points – January 2018, Connoisseurs Guide to California 2016 Mariah Vineyard Zinfandel 89 Points – January 2018, Connoisseurs Guide to California 92 Points/Editor’s Choise – Wine Enthusiast, November 2018 Gold – Best of Class – 2019 San Francisco -

4 Iconic, Delicious Zindandels to Try

| Back | Text Size: https://triblive.com/lifestyles/fooddrink/14094413-74/4-iconic-delicious-zindandels-to-try 4 iconic, delicious Zindandels to try Dave DeSimone | Wednesday, Sept. 19, 2018, 12:03 a.m. Enjoy a full-range of fruity, yet beautifully balanced California Zinfandels. Mid-September marks a critical moment for zinfandel, the granddaddy of California’s red wine grapes. If growers allow zinfandel clusters to linger on the vines until October, then sugar levels continue rising as the grapes soak up California’s glorious autumn sun. More sugar means more potential alcohol. During the ’90s and early 2000s, alcohol levels mounted alarmingly in a majority of zinfandels. Many wines attained alcohol by volume in the upper-15 percent range. Some even tipped over 16 percent. More alcohol became the norm especially in so- called “cult” zinfandels. Monster alcohol, overripe fruit and pronounced oak influences found favor with prominent wine critics. They typically gave “bigger” wines higher numerical ratings on the 100-point rating scales then dominating consumer attentions. More recently as 100- point scales have become less prominent, sanity has slowly returned. Increasingly, California producers pick zinfandel earlier and throttle back to craft more balanced bottles. Drinkability and compatibility with food have regained importance. The movement represents a return to the zinfandel traditions of the mid-20th century when most wines comfortably landed between 12.5 to 14.5 percent alcohol by volume. The nonprofit association “Zinfandel Advocates Producers,” or “ZAP,” for short, leads the push for appreciating zinfandels as table wines. ZAP offers a terrific place to learn more at Zinfandel.org . -

2014 Estate Pinot Noir San Ta C R U Z Mounta Ins

Few wine regions on earth can match Santa Cruz Mountains’ climates, soils and vertigo inspiring views. Set high in the mountains overlooking California’s Silicon Valley, the Thomas Fogarty Winery has been making single-vineyard Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Merlot and Cabernet from the SCM appellation since 1981. Fogarty’s two estates are divided into micro-vineyards, ranging from .25 to 5.25 acres, based on soil and topography. All are maritime (10-18 miles to Pacific), cool-climate (Regions I and II), high-elevation (1600-2300 feet), low yielding (1-3 tons per acre) and mountainous. The winery was founded by Dr. Thomas Fogarty, a Stanford cardiovascular surgeon and world-renowned inventor. 2014 ESTATE PINOT NOIR SAN TA C R U Z MOUNTA INS VINEYARD TECHNICAL DATA Our Santa Cruz Mountains Pinot Noir is sourced from vineyards from APPELLATION four distinct regions within the Santa Cruz Mountains AVA: the fractured 100% Santa Cruz Mountains shales of our Estate Vineyards high upon Skyline Blvd, coastal W INEGRO WER Corralitos, the cool coastal La Honda region and the Summit Rd area, Nathan Kandler which has the highest elevations in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Each vineyard is vinified to highlight it's own signature identity; this blend VINE YARD S harmonizes and intensifies the regional Santa Cruz Mountain character. 26% La Vida Bella (Corralitos), 24% Mindego Ridge (La Honda), 15% Muns (Summit), VINTAGE 13% Will's Cabin (Skyline), 8% Roberta's Vineyard (Summit), 2014 was the second consecutive drought vintage and featured the 4% Kent Berry (Summit) earliest harvesting in our 30+ year history.