Soil Survey Laboratory Information Manual, Version 2.0 (SSIR No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vanadium Pentoxide and Other Inorganic Vanadium Compounds

This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organization, or the World Health Organization. Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 29 VANADIUM PENTOXIDE AND OTHER INORGANIC VANADIUM COMPOUNDS Note that the layout and pagination of this pdf file are not identical to the printed CICAD First draft prepared by Dr M. Costigan and Mr R. Cary, Health and Safety Executive, Liverpool, United Kingdom, and Dr S. Dobson, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Huntingdon, United Kingdom Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organization, and the World Health Organization, and produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals. World Health Organization Geneva, 2001 The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), established in 1980, is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Labour Organization (ILO), and the World Health Organization (WHO). The overall objectives of the IPCS are to establish the scientific basis for assessment of the risk to human health and the environment from exposure to chemicals, through international peer review processes, as a prerequisite for the promotion of chemical safety, and to provide technical assistance in strengthening national capacities for the sound management -

Soil Acidification

viti-notes [grapevine nutrition] Soil acidifi cation Viti-note Summary: Characteristics of acidic soils • Soil pH Calcium and magnesium are displaced • Soil acidifi cation in by aluminium (Al3+) and hydrogen (H+) vineyards and are leached out of the soil. Acidic soils below pH 6 often have reduced • Characteristics of acidic populations of micro-organisms. As soils microbial activity decreases, nitrogen • Acidifying fertilisers availability to plants also decreases. • Effect of soil pH on Sulfur availability to plants also depends rate of breakdown of on microbial activity so in acidic soils, ammonium to nitrate where microbial activity is reduced, Figure 1. Effect of soil pH on availability of minerals sulfur can become unavailable. (Sulfur • Management of defi ciency is not usually a problem for acidifi cation Soil pH vineyards as adequate sulfur can usually • Correction of soil pH All plants and soil micro-organisms have be accessed from sulfur applied as foliar with lime preferences for soil within certain pH fungicides). ranges, usually neutral to moderately • Strategies for mature • Phosphorus availability is reduced at acid or alkaline. Soil pH most suitable vines low pH because it forms insoluble for grapevines is between 5.5 and 8.5. phosphate compounds with In this range, roots can acquire nutrients aluminium, iron and manganese. from the soil and grow to their potential. As soils become more acid or alkaline, • Molybdenum is seldom defi cient in grapevines become less productive. It is neutral to alkaline soils but can form important to understand the impacts of insoluble compounds in acid soils. soil pH in managing grapevine nutrition, • In strongly acidic soil (pH <5), because the mobility and availability of aluminium may become freely nutrients is infl uenced by pH (Figure 1). -

Development Direction of the Soil-Formation Processes for Reclaimed Soda Solonetz-Solonchak Soils of the Ararat Valley During Their Cultivation

Annals of Agrarian Science 16 (2018) 69e74 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Annals of Agrarian Science journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/annals-of-agrarian- science Development direction of the soil-formation processes for reclaimed soda solonetz-solonchak soils of the Ararat valley during their cultivation R.R. Manukyan National Agrarian University of Armenia, 74, Teryan Str., Yerevan, 0009, Armenia article info abstract Article history: The data of the article show that the long-term cultivation of reclaimed sodium solonetz-solonchak soils Received 29 May 2017 entails to further improvement of their properties and in many parameters of chemical compositions of Accepted 19 August 2017 soil solution and soil-absorbing complex they come closer to irrigated meadow-brown soils in the period Available online 6 February 2018 of 15e20 years of agricultural development. The analysis of the experimental research by the method of non-linear regression shows, that for the enhancement of some yield determining parameters to the Keywords: level of irrigated meadow-brown soils, a time period of 30e40 years of soil-formation processes is Soil-formation processes needed and longer time is necessary for humidification. The forecast of soil-formation processes for the Reclaimed soda solonetz-solonchaks fi Irrigated meadow-brown soils long-term period, allows to reveal the intensity and orientation of development of the speci ed pro- fi fi Multi-year cultivation cesses and to develop the scienti cally-justi ed actions for their further improvement. Improvement © 2018 Agricultural University of Georgia. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access Forecasting article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014 International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps

ISSN 0532-0488 WORLD SOIL RESOURCES REPORTS 106 World reference base for soil resources 2014 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 Cover photographs (left to right): Ekranic Technosol – Austria (©Erika Michéli) Reductaquic Cryosol – Russia (©Maria Gerasimova) Ferralic Nitisol – Australia (©Ben Harms) Pellic Vertisol – Bulgaria (©Erika Michéli) Albic Podzol – Czech Republic (©Erika Michéli) Hypercalcic Kastanozem – Mexico (©Carlos Cruz Gaistardo) Stagnic Luvisol – South Africa (©Márta Fuchs) Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: SALES AND MARKETING GROUP Information Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00100 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 Web site: http://www.fao.org WORLD SOIL World reference base RESOURCES REPORTS for soil resources 2014 106 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps Update 2015 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Good Practices for the Preparation of Digital Soil Maps

UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONÓMICAS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS AGROALIMENTARIAS GOOD PRACTICES FOR THE PREPARATION OF DIGITAL SOIL MAPS Resilience and comprehensive risk management in agriculture Inter-american Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture University of Costa Rica Agricultural Research Center UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONÓMICAS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS AGROALIMENTARIAS GOOD PRACTICES FOR THE PREPARATION OF DIGITAL SOIL MAPS Resilience and comprehensive risk management in agriculture Inter-american Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture University of Costa Rica Agricultural Research Center GOOD PRACTICES FOR THE PREPARATION OF DIGITAL SOIL MAPS Inter-American institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), 2016 Good practices for the preparation of digital soil maps by IICA is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/) Based on a work at www.iica.int IICA encourages the fair use of this document. Proper citation is requested. This publication is also available in electronic (PDF) format from the Institute’s Web site: http://www.iica. int Content Editorial coordination: Rafael Mata Chinchilla, Dangelo Sandoval Chacón, Jonathan Castro Chinchilla, Foreword .................................................... 5 Christian Solís Salazar Editing in Spanish: Máximo Araya Acronyms .................................................... 6 Layout: Sergio Orellana Caballero Introduction .................................................. 7 Translation into English: Christina Feenny Cover design: Sergio Orellana Caballero Good practices for the preparation of digital soil maps................. 9 Printing: Sergio Orellana Caballero Glossary .................................................... 15 Bibliography ................................................. 18 Good practices for the preparation of digital soil maps / IICA, CIA – San Jose, C.R.: IICA, 2016 00 p.; 00 cm X 00 cm ISBN: 978-92-9248-652-5 1. -

Soil Acidification

Soil Acidification and Pesticide Management pH 5.1 November 14, 2018 MSU Pesticide Education Program pH 3.8 Image courtesy Rick Engel Clain Jones [email protected] 406-994-6076 MSU Soil Fertility Extension What happened here? Image by Sherrilyn Phelps, Sask Pulse Growers Objectives Specifically, I will: 1. Show prevalence of acidification in Montana (similar issue in WA, OR, ID, ND, SD, CO, SK and AB) 2. Review acidification’s cause and contributing factors 3. Show low soil pH impact on crops 4. Explain how this relates to efficacy and persistence of pesticides (specifically herbicides) 5. Discuss steps to prevent or minimize acidification Prevalence: MT counties with at least one field with pH < 5.5 Symbol is not on location of field(s) 40% of 20 random locations in Chouteau County have pH < 5.5. Natural reasons for low soil pH . Soils with low buffering capacity (low soil organic matter, coarse texture, granitic rather than calcareous) . Historical forest vegetation soils < pH than historical grassland . Regions with high precipitation • leaching of nitrate and base cations • higher yields, receive more N fertilizer • often can support continuous cropping and N each yr Agronomic reasons for low soil pH • Nitrification of ammonium-based N fertilizer above plant needs - + ammonium or urea fertilizer + air + H2O→ nitrate (NO3 ) + acid (H ) • Nitrate leaching – less nitrate uptake, less root release of basic - - anions (OH and HCO3 ) to maintain charge balance • Crop residue removal of Ca, Mg, K (‘base’ cations) • No-till concentrates acidity where N fertilizer applied • Legumes acidify their rooting zone through N-fixation. Perennial legumes (e.g., alfalfa) more than annuals (e.g., pea), but much less than fertilization of wheat. -

A New Era of Digital Soil Mapping Across Forested Landscapes 14 Chuck Bulmera,*, David Pare´ B, Grant M

CHAPTER A new era of digital soil mapping across forested landscapes 14 Chuck Bulmera,*, David Pare´ b, Grant M. Domkec aBC Ministry Forests Lands Natural Resource Operations Rural Development, Vernon, BC, Canada, bNatural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentian Forestry Centre, Quebec, QC, Canada, cNorthern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, St. Paul, MN, United States *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Soil maps provide essential information for forest management, and a recent transformation of the map making process through digital soil mapping (DSM) is providing much improved soil information compared to what was available through traditional mapping methods. The improvements include higher resolution soil data for greater mapping extents, and incorporating a wide range of environmental factors to predict soil classes and attributes, along with a better understanding of mapping uncertainties. In this chapter, we provide a brief introduction to the concepts and methods underlying the digital soil map, outline the current state of DSM as it relates to forestry and global change, and provide some examples of how DSM can be applied to evaluate soil changes in response to multiple stressors. Throughout the chapter, we highlight the immense potential of DSM, but also describe some of the challenges that need to be overcome to truly realize this potential. Those challenges include finding ways to provide additional field data to train models and validate results, developing a group of highly skilled people with combined abilities in computational science and pedology, as well as the ongoing need to encourage communi- cation between the DSM community, land managers and decision makers whose work we believe can benefit from the new information provided by DSM. -

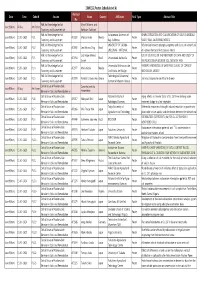

Poster Presentation Schedule

20WCSS_Poster Schedule(vol.6) Abstract Date Time Code-N Session Name Country Affiliation Final Type Abstract Title No Folk Soil Knowledge for Soil Myriel Milicevic and June 9(Mon) All day Art Poster Taxonomy and Assessment-art Ruttikorn Vuttikorn Folk Soil Knowledge for Soil Autonomous University of CHARACTERIZATION AND CLASSIFICATION OF SOILS IN MEXICALI June 9(Mon) 15:30~16:20 P1-1 AF2388 Monica Aviles Mexico Poster Taxonomy and Assessment Baja California VALLEY, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO Folk Soil Knowledge for Soil UNIVERSITY OF CUIABA - Relationship between phytophysiognomy and classes of wetland soil June 9(Mon) 15:30~16:20 P1-2 AF2892 Leo Adriano Chig Brazil Poster Taxonomy and Assessment UNIC/INAU - NATIONAL of northern Pantanal Mato Grosso - Brazil Folk Soil Knowledge for Soil Luiz Felipe Moreira USE OF SIG TOOLS IN THE TREATMENT OF DATA AND STUDY OF June 9(Mon) 15:30~16:20 P1-3 AF2934 Brazil Universidade de Brasilia Poster Taxonomy and Assessment Cassol THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOIL, GEOLOGY AND Folk Soil Knowledge for Soil Universidad Michoacana de FARMER'S KNOWLEDGE OF LAND AND CLASSES OF CORN OF June 9(Mon) 15:30~16:20 P1-4 AF2977 Maria Alcala Mexico Poster Taxonomy and Assessment San Nicolas de Hidalgo MICHOACAN, MEXICO Folk Soil Knowledge for Soil Technological Educational June 9(Mon) 15:30~16:20 P1-5 AF2979 Pantelis E. Barouchas Greece Poster Soil mass balance for an Alfisol in Greece Taxonomy and Assessment Institute of Western Greece Critical Issues of Radionuclide Center for Land Use June 9(Mon) All day Art Poster Behavior -

Pedometric Mapping of Key Topsoil and Subsoil Attributes Using Proximal and Remote Sensing in Midwest Brazil

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE AGRONOMIA E MEDICINA VETERINÁRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM AGRONOMIA PEDOMETRIC MAPPING OF KEY TOPSOIL AND SUBSOIL ATTRIBUTES USING PROXIMAL AND REMOTE SENSING IN MIDWEST BRAZIL RAÚL ROBERTO POPPIEL TESE DE DOUTORADO EM AGRONOMIA BRASÍLIA/DF MARÇO/2020 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE AGRONOMIA E MEDICINA VETERINÁRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM AGRONOMIA PEDOMETRIC MAPPING OF KEY TOPSOIL AND SUBSOIL ATTRIBUTES USING PROXIMAL AND REMOTE SENSING IN MIDWEST BRAZIL RAÚL ROBERTO POPPIEL ORIENTADOR: Profa. Dra. MARILUSA PINTO COELHO LACERDA CO-ORIENTADOR: Prof. Titular JOSÉ ALEXANDRE MELO DEMATTÊ TESE DE DOUTORADO EM AGRONOMIA BRASÍLIA/DF MARÇO/2020 ii iii REFERÊNCIA BIBLIOGRÁFICA POPPIEL, R. R. Pedometric mapping of key topsoil and subsoil attributes using proximal and remote sensing in Midwest Brazil. Faculdade de Agronomia e Medicina Veterinária, Universidade de Brasília- Brasília, 2019; 105p. (Tese de Doutorado em Agronomia). CESSÃO DE DIREITOS NOME DO AUTOR: Raúl Roberto Poppiel TÍTULO DA TESE DE DOUTORADO: Pedometric mapping of key topsoil and subsoil attributes using proximal and remote sensing in Midwest Brazil. GRAU: Doutor ANO: 2020 É concedida à Universidade de Brasília permissão para reproduzir cópias desta tese de doutorado e para emprestar e vender tais cópias somente para propósitos acadêmicos e científicos. O autor reserva outros direitos de publicação e nenhuma parte desta tese de doutorado pode ser reproduzida sem autorização do autor. ________________________________________________ Raúl Roberto Poppiel CPF: 703.559.901-05 Email: [email protected] Poppiel, Raúl Roberto Pedometric mapping of key topsoil and subsoil attributes using proximal and remote sensing in Midwest Brazil/ Raúl Roberto Poppiel. -- Brasília, 2020. -

Alumohydrocalcite Caal2(CO3)2(OH)4 • 3H2O C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Triclinic

Alumohydrocalcite CaAl2(CO3)2(OH)4 • 3H2O c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Triclinic. Point Group: 1or1. As fibers and needles, to 2.5 mm; commonly in radial aggregates and spherulites, feltlike crystal linings, and powdery to chalky masses. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {100} perfect; {010} imperfect. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 2.5 D(meas.) = 2.21–2.24 D(calc.) = 2.213 Decomposes in boiling H2O to calcite and hydrous aluminum oxide. Optical Properties: Transparent to opaque. Color: Chalky white to pale blue, pale yellow, cream, gray; pale rose or brownish pink to dark violet in chromian varieties; colorless in transmitted light. Luster: Vitreous to pearly, earthy. Optical Class: Biaxial (–). Orientation: X = b; extinction inclined 6◦–10◦. α = 1.485–1.502 β = 1.553–1.563 γ = 1.570–1.585 2V(meas.) = 64◦ 2V(calc.) = 50◦–55◦ Cell Data: Space Group: P 1or P 1 (chromian). a = 6.498(3) b = 14.457(4) c = 5.678(3) α =95.83(5)◦ β =93.23(3)◦ γ =82.24(3)◦ Z=2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany. 6.25 (100), 6.50 (70), 3.23 (60), 2.039 (50), 2.519 (40), 7.21 (30), 2.860 (30) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) (1) (2) (3) CO2 24.2 26.4 26.19 CaO 17.8 16.5 16.68 Al2O3 31.3 22.0 30.33 H2O 26.7 26.6 26.80 Cr2O3 8.3 Total 100.0 99.8 100.00 2− 1− (1) Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany; (CO3) , (OH) , and H2O confirmed by IR. -

Nitrogen Deposition Contributes to Soil Acidification in Tropical Ecosystems

Global Change Biology Global Change Biology (2014), doi: 10.1111/gcb.12665 Nitrogen deposition contributes to soil acidification in tropical ecosystems XIANKAI LU1 , QINGGONG MAO1,2,FRANKS.GILLIAM3 ,YIQILUO4 and JIANGMING MO 1 1Key Laboratory of Vegetation Restoration and Management of Degraded Ecosystems, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China, 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China, 3Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755-2510, USA, 4Department of Microbiology and Plant Biology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA Abstract Elevated anthropogenic nitrogen (N) deposition has greatly altered terrestrial ecosystem functioning, threatening eco- system health via acidification and eutrophication in temperate and boreal forests across the northern hemisphere. However, response of forest soil acidification to N deposition has been less studied in humid tropics compared to other forest types. This study was designed to explore impacts of long-term N deposition on soil acidification pro- cesses in tropical forests. We have established a long-term N-deposition experiment in an N-rich lowland tropical for- À1 À1 est of Southern China since 2002 with N addition as NH4NO3 of 0, 50, 100 and 150 kg N ha yr . We measured soil acidification status and element leaching in soil drainage solution after 6-year N addition. Results showed that our study site has been experiencing serious soil acidification and was quite acid-sensitive showing high acidification < < (pH(H2O) 4.0), negative water-extracted acid neutralizing capacity (ANC) and low base saturation (BS, 8%) through- out soil profiles. Long-term N addition significantly accelerated soil acidification, leading to depleted base cations and decreased BS, and further lowered ANC. -

Behaviour and Geotechnical Properties of Residual Soils and Allophane Clays

Wesley, L. (2009). Behaviour and geotechnical properties of residual soils and allophane clays. Obras y Proyectos 6, 5-10. Behaviour and geotechnical properties of residual soils and allophane clays Fecha de entrega: 20 de Septiembre 2009 Fecha de aceptación: 23 de Noviembre 2009 Laurie Wesley Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, the University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand, [email protected] An overview of the properties of residual soils is given in the first part En la primera parte del artículo se entrega una descripción general de of the paper. The different processes by which residual and sedimentary los suelos residuales. Se detallan los diferentes procesos en los cuales son soils are formed are described, and the need to be aware that procedures formados los suelos residuales y sedimentarios, poniendo hincapié en la applicable to sedimentary soils do not necessarily apply to residual soils necesidad de estar atento a que los procedimientos aplicados a los suelos is emphasised. In particular, it is shown that the log scale normally sedimentarios no son necesariamente aplicables a los suelos residuales. used for presenting oedometer test results is not appropriate or relevant En particular, se muestra que la escala logarítmica generalmente usada to residual soils. The second part of the paper gives an account of para presentar resultados de ensayos edométricos no es apropiada o the special properties of allophane clays. Their abnormally high water pertinente para suelos residuales. La segunda parte del artículo da content and Atterberg limits are described, and it is shown that despite cuenta de las propiedades especiales de arcillas alofánicas.