Battleground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

The Interaction Between the Missionaries of the Cape

THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THE MISSIONARIES OF THE CAPE EASTERN FRONTIER AND THE COLONIAL AUTHORITIES IN THE ERA OF SIR GEORGE GREY, 1854 - 1861. Constance Gail Weldon Pietermaritzburg, December 1984* Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Natal, 1984. CONTENTS Page Abstract i List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Sir George Grey and his ’civili zing mission’ 16 Chapter 3 The missionaries and Grey 1854-6 55 Chapter 4 The Cattle Killing 1856/7 99 Chanter 5 The Aftermath of the Cattle Killing (till 1860s) 137 Chapter 6 Conclusion 174 Appendix A Principal mission stations on the frontier 227 Appendix B Wesleyan Methodist and Church of Scotland Missionaries 228 Appendix C List of magistrates and chiefs 229 Appendix D Biographical Notes 230 Select Bibliography 233 List of photographs and maps Between pages 1. Sir George Grey - Governor 15/16 2. Map showing Cape eastern frontier and principal military posts 32/33 3. Map showing the principal frontier mission stations 54/55 4. Photographs showing Lovedale trade departments 78/79 5. Map showing British Kaffraria and principal chiefs 98/99 6. Sir George Grey - 'Romantic Imperialist' 143/144 7. Sir George Grey - civilian 225/226 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge with thanks the financial assistance rendered by the Human Sciences Research Council towards the costs of this research. Opinions expressed or conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not to be regarded as those of the Human Sciences Research Council. -

Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, Politician, Generalissimus and Dictator

Military Despatches Vol 34 April 2020 Flip-flop Generals that switch sides Surviving the Arctic convoys 93 year WWII veteran tells his story Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, politician, Generalissimus and dictator Aarthus Air Raid RAF Mosquitos destory Gestapo headquarters For the military enthusiast CONTENTS April 2020 Page 14 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Russian Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 34 were humorous, some A matter of survival were clever, while others 6 This month we continue with were downright crude. Ten generals that switched sides our look at fish and fishing for Imagine you’re a soldier heading survival. into battle under the leadership of Part of Hipe’s “On the a general who, until very recently 30 couch” series, this is an been trying very hard to kill you. interview with one of How much faith and trust would Ranks you have in a leader like that? This month we look at the author Herman Charles Army of the Republic of Viet- Bosman’s most famous 20 nam (ARVN), the South Viet- characters, Oom Schalk Social media - Soldier’s menace namese army. A taxi driver was shot Lourens. Hipe spent time in These days nearly everyone has dead in an ongoing Hanover Park, an area a smart phone, laptop or PC plagued with gang with access to the Internet and Quiz war between rival taxi to social media. -

King William's Town

http://ngtt.journals.ac.za Hofmeyr, JW (Hoffie) University of the Free State and Hofmeyr, George S (†) (1945-2009) Former Director of the National Monuments Council of South Africa Establishing a stable society for the sake of ecclesiastical expansion in a frontier capital (King William’s Town) in the Eastern Cape: the pensioners and their village between 1855 and 1861 ABSTRACT For many different reasons, the Eastern Cape area has long been and remains one of the strong focus points of general, political and ecclesiastical historians. In this first article of a series on a frontier capital (King William’s Town) in the Eastern Cape, I wish to focus on a unique socio economic aspect of the fabric of the Eastern Cape society in the period between 1855 and 1861 i.e. the establishment of a Pensioners’ Village. It also touches on certain aspects of the process of colonization in the Eastern Cape. Eventually all of this had, besides many other influences, also an influence on the further expansion of Christianity in the frontier context of the Eastern Cape. In a next article the focus will therefore be on a discussion and analysis of the expansion of missionary work in this frontier context against the background of the establishment of the Pensioners’ Village. 1. INTRODUCTION The British settlement of the Eastern Cape region was a long drawn out process, besides that of the local indigenous people, the Xhosa from the north and the Afrikaner settlers from the western Cape. All these settlements not only had a clear socio economic and political effect but it eventually also influenced the ecclesiastical scene. -

A Short Chronicle of Warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau* Khoisan Wars tween whites, Khoikhoi and slaves on the one side and the nomadic San hunters on the other Khoisan is the collective name for the South Afri- which was to last for almost 200 years. In gen- can people known as Hottentots and Bushmen. eral actions consisted of raids on cattle by the It is compounded from the first part of Khoi San and of punitive commandos which aimed at Khoin (men of men) as the Hottentots called nothing short of the extermination of the San themselves, and San, the names given by the themselves. On both sides the fighting was ruth- Hottentots to the Bushmen. The Hottentots and less and extremely destructive of both life and Bushmen were the first natives Dutch colonist property. encountered in South Africa. Both had a relative low cultural development and may therefore be During 18th century the threat increased to such grouped. The Colonists fought two wars against an extent that the Government had to reissue the the Hottentots while the struggle against the defence-system. Commandos were sent out and Bushmen was manned by casual ranks on the eventually the Bushmen threat was overcome. colonist farms. The Frontier War (1779-1878) The KhoiKhoi Wars This term is used to cover the nine so-called "Kaffir Wars" which took place on the eastern 1st Khoikhoi War (1659-1660) border of the Cape between the Cape govern- This was the first violent reaction of the Khoikhoi ment and the Xhosa. -

The Third War of Dispossession and Resistance in the Cape of Good Hope Colony, 1799–1803

54 “THE WAR TOOK ITS ORIGINS IN A MISTAKE”: THE THIRD WAR OF DISPOSSESSION AND RESISTANCE IN THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE COLONY, 1799–1803 Denver Webb, University of Fort Hare1 Abstract The early colonial wars on the Cape Colony’s eastern borderlands and western Xhosaland, such as the 1799–1803 war, have not received as much attention from military historians as the later wars. This is unexpected since this lengthy conflict was the first time the British army fought indigenous people in southern Africa. This article revisits the 1799–1803 war, examines the surprisingly fluid and convoluted alignments of participants on either side, and analyses how the British became embroiled in a conflict for which they were unprepared and for which they had little appetite. It explores the micro narrative of why the British shifted from military action against rebellious Boers to fighting the Khoikhoi and Xhosa. It argues that in 1799, the British stumbled into war through a miscalculation – a mistake which was to have far-reaching consequences on the Cape’s eastern frontier and in western Xhosaland for over a century. Introduction The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial wars on the Cape Colony’s eastern borderlands and western Xhosaland (emaXhoseni) have received considerable attention from historians. For reasons mostly relating to the availability of source material, the later wars are better known than the earlier ones. Thus the War of Hintsa (1834–35), the War of the Axe (1846–47), the War of Mlanjeni (1850–53) and the War of Ngcayecibi (1877–78) have received far more coverage by contemporaries and subsequently by historians than the eighteenth-century conflicts.2 The first detailed examination of Scientia Militaria, South African the 1799–1803 conflict, commonly known as Journal of Military Studies, Vol the Third Frontier War or third Cape–Xhosa 42, Nr 2, 2014, pp. -

Proquest Dissertations

I^fefl National Library Bibliotheque naiionale • T • 0f Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A0N4 K1A0N4 v'o,/rM<* Volt? rottiU'iKc Our lilu Nolle tit&rtsnca NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualite de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the depend grandement de la qualite quality of the original thesis de la these soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualite ensure the highest quality of superieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec I'universite degree. qui a confere Ie grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualite d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser a pages were typed with a poor desirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originates ont ete university sent us an inferior dactylographies a I'aide d'un photocopy. ruban use ou si I'univeioite nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualite inferieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, meme partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, a la Loi canadienne sur Ie droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30, et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subsequents. Canada Maqoma: Xhosa Resistance to the Advance of Colonial Hegemony (1798-1873) by Timothy J. -

Customary Marriage and Family Practices That Discriminate Against Amaxhosa Women: a Critical Study of Selected Isixhosa Literary Texts

CUSTOMARY MARRIAGE AND FAMILY PRACTICES THAT DISCRIMINATE AGAINST AMAXHOSA WOMEN: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECTED ISIXHOSA LITERARY TEXTS BY PHELIWE YVONNE MBATYOTI Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES of the UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE SUPERVISOR: Professor C.R. Botha Date submitted: JUNE 2018 DECLARATION I Pheliwe Yvonne Mbatyoti, student number 200600881 declare that CUSTOMARY MARRIAGE AND FAMILY PRACTICES THAT DISCRIMINATE AGAINST AMAXHOSA WOMEN: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECTED ISIXHOSA LITERARY TEXTS is my own work, and that it has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other university. Student: Pheliwe Yvonne Mbatyoti Signature: Date: 30 June 2018 i DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my mother Mrs. Mbatyoti Nonani Nosipho Gladys for her unconditional support and motivation in all my endeavours in life. To my children I say follow your LIGHT. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks goes to my Supervisor Prof C.R. Botha for his tireless support and encouragement, during this long road to success, Sukwini you are a guardian angel in times of need. To my colleague, Dr Z W Saul, for his support during my studies. Appreciation is also extended to Qhama, Phiwe and Siyanda for believing in my capabilities, Ozoemena Ababalwe, my grandchild you kept me company all the way, uThixo akusikelele. iii ABSTRACT In many parts of Africa, the cultural practices and customs that were in use over the ages are still largely in place today. Many of these practices discriminate against individuals and compromise their human rights, particularly the rights of African women. -

Amathole District Municipality

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY 2012 - 2017 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN Amathole District Municipality IDP 2012-2017 – Version 1 of 5 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENT The Executive Mayor’s Foreword 4 Municipal Manager’s Message 5 The Executive Summary 7 Report Outline 16 Chapter 1: The Vision 17 Vision, Mission and Core Values 17 List of Amathole District Priorities 18 Chapter 2: Demographic Profile of the District 31 A. Introduction 31 B. Demographic Profile 32 C. Economic Overview 38 D. Analysis of Trends in various sectors 40 Chapter 3: Status Quo Assessment 42 1 Local Economic Development 42 1.1 Economic Research 42 1.2 Enterprise Development 44 1.3 Cooperative Development 46 1.4 Tourism Development and Promotion 48 1.5 Film Industry 51 1.6 Agriculture Development 52 1.7 Heritage Development 54 1.8 Environmental Management 56 1.9 Expanded Public Works Program 64 2 Service Delivery and Infrastructure Investment 65 2.1 Water Services (Water & Sanitation) 65 2.2 Solid Waste 78 2.3 Transport 81 2.4 Electricity 2.5 Building Services Planning 89 2.6 Health and Protection Services 90 2.7 Land Reform, Spatial Planning and Human Settlements 99 3 Municipal Transformation and Institutional Development 112 3.1 Organizational and Establishment Plan 112 3.2 Personnel Administration 124 3.3 Labour Relations 124 3.4 Fleet Management 127 3.5 Employment Equity Plan 129 3.6 Human Resource Development 132 3.7 Information Communication Technology 134 4 Municipal Financial Viability and Management 136 4.1 Financial Management 136 4.2 Budgeting 137 4.3 Expenditure -

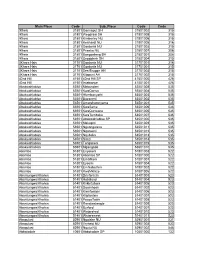

Mainplace Codelist.Xls

Main Place Code Sub_Place Code Code !Kheis 31801 Gannaput SH 31801002 315 !Kheis 31801 Wegdraai SH 31801008 315 !Kheis 31801 Kimberley NU 31801006 315 !Kheis 31801 Kenhardt NU 31801005 316 !Kheis 31801 Gordonia NU 31801003 315 !Kheis 31801 Prieska NU 31801007 306 !Kheis 31801 Boegoeberg SH 31801001 306 !Kheis 31801 Grootdrink SH 31801004 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 316 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Ses-Brugge AH 31701003 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Klippunt AH 31701002 315 42nd Hill 41501 42nd Hill SP 41501000 426 42nd Hill 41501 Intabazwe 41501001 426 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mabundeni 53501008 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQonsa 53501004 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Hlambanyathi 53501003 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Bazaneni 53501002 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Amatshamnyama 53501001 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaSeme 53501006 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQunwane 53501005 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaTembeka 53501007 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Abakwahlabisa SP 53501000 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Makopini 53501009 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Ngxongwana 53501011 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqotweni 53501012 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqubeka 53501013 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Sitezi 53501014 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Tanganeni 53501015 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mgangado 53501010 535 Abambo 51801 Enyokeni 51801003 522 Abambo 51801 Abambo SP 51801000 522 Abambo 51801 Emafikeni 51801001 522 Abambo 51801 Eyosini 51801004 522 Abambo 51801 Emhlabathini 51801002 522 Abambo 51801 KwaMkhize 51801005 522 Abantungwa/Kholwa 51401 Driefontein 51401003 523 -

Amathole District Municipality WETLAND REPORT | 2017

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY WETLAND REPORT | 2017 LOCAL ACTION FOR BIODIVERSITY (LAB): WETLANDS SOUTH AFRICA Biodiversity for Life South African National Biodiversity Institute Full Program Title: Local Action for Biodiversity: Wetland Management in a Changing Climate Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Southern Africa Cooperative Agreement Number: AID-674-A-14-00014 Contractor: ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability – Africa Secretariat Date of Publication: June 2017 DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FOREWORD Amathole District Municipality is situated within the Amathole District Municipality is also prone to climate central part of the Eastern Cape Province, which lies change and disaster risk such as wild fires, drought in the southeast of South Africa and borders the and floods. Wetland systems however can be viewed Indian Ocean. Amathole District Municipality has as risk reduction ecological infrastructure. Wetlands a land area of 21 595 km² with approximately 200 also form part of the Amathole Mountain Biosphere km of coastline stretching along the Sunshine Coast Reserve, which is viewed as a conservation and from the Fish River to just south of Hole in the Wall sustainable development flagship initiative. along the Wild Coast. Amathole District Municipality coastline spans two bio-geographical regions, namely Amathole District Municipality Integrated the warm temperate south coast and the sub-tropical Development Plan (IDP) recognises the importance east coast. of wetlands within the critical biodiversity areas of the Spatial Development Framework (SDF). Amathole District Municipality is generally in a good Sustainable development principles are an natural state; 83.3% of land comprises of natural integral part of Amathole District Municipality’s areas, whilst only 16.7% are areas where no natural developmental approach as they are captured in the habitat remains. -

Literatura, Lei De Terras E Colonialismo Em Sword and Assegai (África Do Sul, Década De 1890)

DOI: 10.47694/issn.2674-7758.v3.i8.2021.3050 ANNA HOWARTH E AS GUERRAS DAS FRONTEIRAS: LITERATURA, LEI DE TERRAS E COLONIALISMO EM SWORD AND ASSEGAI (ÁFRICA DO SUL, DÉCADA DE 1890) Evander Ruthieri da Silva1 Resumo: O período entre as décadas de 1870 e 1890 marcou um contexto de transformações sociais e políticas nos territórios localizados ao sul da África, ocasionadas pela expansão econômica e territorial decorrente das atividades na mineração e agricultura. Diversas medidas foram adotadas pelo colonato branco com o objetivo de controlar as terras ancestrais e a mão de obra da população negra, em especial, a legislação de terras. Diante desse quadro, o artigo concentra-se em Sword and Assegai (1899), de Anna Howarth, um romance de aventura ambientado nas “guerras das fronteiras” da região oriental da Colônia do Cabo (atualmente África do Sul) entre as décadas de 1830 a 1850. O destaque recai na caracterização dos guerreiros Xhosa, compreendendo a ênfase da romancista no “barbarismo” como uma forma de legitimação pública das práticas políticas coloniais, em especial, da apropriação de terras africanas empreendida pela elite colonial. Palavras-chave: História e Literatura. África do Sul. Colonialismo. ANNA HOWARTH AND THE FRONTIER WARS: LITERATUR, LAND LEGISLATION AND COLONIALISM IN SWORD AND ASSEGAI (SOUTH AFRICA, 1890s) Abstract: The period between the 1870s and 1890s marked a context of social and political changes in southern Africa, caused by economic and territorial expansion resulting from mining and agriculture activities. Several measures were adopted by white colonizers in order to control 30 African ancestral lands and workforce, such as by land legislation.