I Believe in Unicorns by Michael Morpurgo (Short-Story Version)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Childhood Early Career Starting His Writing Middle Age

Introduction Michael Morpurgo ,who is admired by many people, adults and children, for being an author that they enjoy reading. He is also famous for being author of many books such as War Horse,which became a popular stage show; Butterfly Lion,which won the Nestle smarties book award in 1996; Kensuke’s Kingdom, which won the children’s book award in 2000 and Private Peaceful,which was his 100th published book. Many people love his books and he is considered one of the best authors in the world. Read on to find more about this british author. C hildhood Michael was born on October the 5th 1943 (his star sign was a libra.) His father was an actor and his mother was an actress too! He grew up in St Albans, England. When Michael was younger he used to visit the ` Isles of Scilly`. Early Career Michael educated at university,(King's university to be precise) After that, he became a primary school teacher in Kent. It was at his primary school he realised his hidden talent for writing. It is spoken that the children enjoyed Michaels stories more than the stories by other authors. Starting his writing Michael has won many awards in literature such as, the Nestle smarties award. His first published book was written in the summer of the year 1974. It was called ‘It Never Rained’ It was 8 years later when he released his best selling novel, War Horse. War Horse is now a worldrenowned book due to the fact it has been one of the bestselling books ever. -

Stretch & Challenge

Stretch & Challenge Engage, explore, Discover Junior School SUMMER TERM 2020 Welcome and Contents As we have been thrown the challenge of remote learning, we have noticed the girls and families using Contents this opportunity to expand and develop even more of Art 3 their interests. With such a positive attitude to learning, Ballet 5 it is an ideal moment to offer further growth through the additional inspiration here. Thank you to everyone Computing 7 involved in adding to this booklet. Current Affairs 9 Drama 11 English 13 French 15 Geography 17 History 19 Mrs Dixon, Head of Francis Holland Junior School Maths 21 Music 23 Engage, Explore and Physical Education 25 Discover PSHE 27 Religious Education 29 We are delighted to introduce this superb enrichment booklet designed specifically with our Junior School Science & Steam 31 girls in mind. Our amazing, resourceful teachers have been looking for material to inspire the girls’ Reading learning further, giving the girls ample opportunity to Year 1 35 be inquisitive, creative and indulge their intellectual Year 2 36 curiosity. These resources can be used to extend the work they do in lessons or to develop new and further Year 3 37 interests. Year 4 38 On a practical note, we would like to draw your Year 5 39 attention to some key features of this document. The Year 6 40 subjects listed on the contents page link to the relevant pages which are then split into content suitable for Thematic Reading EYFS, Key Stage 1, Key Stage 2 or all of the girls. In Adventure Books 41 addition, there are many links within each subject to Fantasy Books 42 online tours, talks, competitions, games, virtual courses as well as books being linked directly to Amazon. -

Supporting Our Work

Supporting our work We are hugely grateful to the I am a UK taxpayer and would like the charity to reclaim many people who generously Gift Aid on my behalf (please tick) ___ give their time, their energy or any donation - large or small - I enclose a donation of £_________made payable to in support of our work. Farms for City Children Pensioners, school children, churches, schools and businesses all help to raise funds for Farms for City Children. You can be part of it too! We want to make sure that as many children as possible can visit our farms. With this in mind, we aim to raise over £300,000 each year, to subsidise the true cost of each child’s place. We must also raise money to maintain the three historic farm properties Feeding the kids at Treginnis which we are so lucky to have. Please update / add my contact details to your If you are a UK taxpayer, you newsletter mailing list: can make your donation under the Gift Aid scheme. This Name:……………………………………………………… allows FFCC to claim back an extra 25p in tax for every £1 Address:…………………………………………………… you donate. ...................................................................... If you would like to make a donation and/or join our e-mail……………….………………………………… mailing list, please fill in your details. Signed:…………………………………………Date………… (Information supplied is confidential and is not passed on to third parties) Please return this page to: Farms for City Children, Administrative Office, Bridge House, 25 Fore Street, Okehampton, Devon, EX20 1DL e-mail: [email protected] Registered Charity number 325120 Winter Newsletter 2010 This autumn we celebrate the The orchards produce an amazing range of local and launch of ‘Wick Court Food traditional apples, perry pears, plums and gages. -

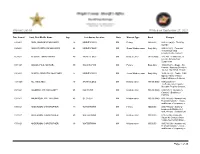

Hamilton County Criminal Court 9/29/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket Trial Date: 09/29/2021 Division: 1 Judge: STEELMAN, BARRY A

CJUSHAND Hamilton County Criminal Court 9/29/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket Trial Date: 09/29/2021 Division: 1 Judge: STEELMAN, BARRY A. State vs. ATKINS , DEDRIC LAMONT aka ATKINS, DEDRICK Silverdale AGGRAVATED ARSON Counts: 1 Thru 1 TCA: 39140302 TIBRS: VANDALISM Counts: 2 Thru 2 TCA: 39140408 TIBRS: 290 Docket #: 310525 Bond Amt: $0.00 Attorney: PERRY, JAY (P.D.) District Attorney: ORTWEIN, FREDERICK LEE Bonding Co.: Order of Court: Active Bond Date: NVC PP Number Times: Case Type: Indictment Filing Date: 9/30/2020 Number of Trial Docket Appearances: 8 Amount Owed on this Case: $0.00 Total Amounts Owed: $765.00 7/21/2021 - PASSED SEPTEMBER 29 2021 FOR SETTLEMENT #1 6/23/2021 - FORMAL ORDER THAT THE DEFENDANT BE REFERRED TO THE MIDDLE TENNESSEE MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTE, FSP FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION. THE PREVIOUS ORDER REGARDING MOCCASIN BEND HEALTH INSTITURE IS HEREBY RESCINDED. #1 6/22/2021 - FORMAL ORDER THAT THE DEFENDANT BE REFERRED TO THE MOCCASIN BEND HEALTH INSTITURE FOR A MAXIMUM OF 30 DAYS FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION. #1 5/26/2021 - ORAL MOTION FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION HEARD AND SUSTAINED - PASSED JULY 21, 2021 FOR SETTLEMENT #1 5/26/2021 - FORMAL ORDER ENTERED DIRECTING FORENSIC EVALUATION #1 State vs. ATKINS , DEDRIC LAMONT aka ATKINS, DEDRICK Silverdale DOMESTIC AGGRAVATED ASSAULT Counts: 1 Thru 1 TCA: 39130102 TIBRS: 13A Docket #: 310526 Bond Amt: $0.00 Attorney: PERRY, JAY (P.D.) District Attorney: Bonding Co.: Order of Court: Active Bond Date: NVC PP Number Times: Case Type: Indictment Filing Date: 9/30/2020 Number of Trial Docket Appearances: 8 Amount Owed on this Case: $0.00 Total Amounts Owed: $765.00 7/21/2021 - PASSED SEPTEMBER 29 2021 FOR SETTLEMENT #1 6/23/2021 - FORMAL ORDER THAT THE DEFENDANT BE REFERRED TO THE MIDDLE TENNESSEE MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTE, FSP FOR FORENSIC EVALUATION. -

Misdemeanor Warrant List

SO ST. LOUIS COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE Page 1 of 238 ACTIVE WARRANT LIST Misdemeanor Warrants - Current as of: 09/26/2021 9:45:03 PM Name: Abasham, Shueyb Jabal Age: 24 City: Saint Paul State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/05/2020 415 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFFIC-9000 Misdemeanor Name: Abbett, Ashley Marie Age: 33 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 03/09/2020 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Abbott, Alan Craig Age: 57 City: Edina State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 09/16/2019 500 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Disorderly Conduct Misdemeanor Name: Abney, Johnese Age: 65 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/18/2016 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Shoplifting Misdemeanor Name: Abrahamson, Ty Joseph Age: 48 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/24/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Trespass of Real Property Misdemeanor Name: Aden, Ahmed Omar Age: 35 City: State: Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 06/02/2016 485 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFF/ACC (EXC DUI) Misdemeanor Name: Adkins, Kyle Gabriel Age: 53 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/28/2013 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Aguilar, Raul, JR Age: 32 City: Couderay State: WI Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/17/2016 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Driving Under the Influence Misdemeanor Name: Ainsworth, Kyle Robert Age: 27 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 11/22/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Theft Misdemeanor ST. -

Reading at the Bishops' C of E and RC Primary School a Guide To

Reading At The Bishops’ C of E and RC Primary School A guide to developing fluency, comprehension and a love of reading Reading for pleasure At the Bishops’ we value reading for pleasure as well as purpose. Books provide us all with a chance to escape into a different world, grow our understanding of a particular interest and rest from other pressures. As such we encourage children on occasions to read for pleasure and NOT be questioned every time they read to or with an adult. Reading to your child Key Stage 2 children still enjoy being read to (even in Year 6!). This time spent 1:1 with children doesn’t have to be long but is highly beneficial to developing many different skills. Many of our children rate it as one of their favourite things to do with their parents/carers. Reading to your child opens up books which may be too difficult for them to read independently, providing them with ideas for their own writing and a love of story. It also allows fluency and expression to be modelled to them. Comprehension Understanding what we have read is essential to our enjoyment of reading along with developing our understanding of the world around us and the vocabulary people use. We are committed to developing comprehension alongside fluency. The questions in the following section aim to assist you in developing your child’s understanding, and engagement with, the text. We try to ask open questions which children respond to in sentences, reasoning their thoughts when appropriate. As well as literal questions – recalling facts, or locating answers which are clearly stated in the text – we ask questions to develop higher order skills that require children to think beyond the literal. -

Rutgers University Glee Club Fall 2020 – Audition Results Tenor 1

Rutgers University Glee Club Fall 2020 – Audition results Congratulations and welcome to the start of a great new year of music making. Please register for the Rutgers University Glee Club immediately – Course 07 701 349. If you are a music major and have any issues with registration please contact Ms. Leibowitz. Non majors with questions please email Dr. Gardner – [email protected]. Glee Club rehearases on Weds nights from 7 to 10 pm and Fridays from 2:50 to 4:10 pm on-line. The zoom link and syllabus is available in Canvas. First rehearsal is this coming Wednesday, September 9th. See you there! Tenor 1 Tenor 2 Baritone Bass Maxwell Domanchich Billy Colletto III Ryan Acevedo James Carson Tin Fung Sean Dekhayser Kyle Cao John DeMarco Jonathan Germosen Steve Franklin Jeffrey Greiner Duff Heitmann Joseph Maldonado James Hwang Tristan Kilper Jonathan Ho Khuti Moses Benjamin Kritz Brian Kong Emerson Katz-Justice Aditya Nibhanupudi Matthew Mallick Matthew Lacognata Seonuk Kim Michael O'Neill Amartya Mani Michael Lazarow Allen Li Michael Schaming Gene Masso Ryan Leibowitz Gabriel Lukijaniuk Xerxes Tata Conor Wall Carl Muhler Sean McBurney Harry Thomas Bobby Weil Julian Perelman Joseph Mezza Zachary Wang John Wilson Caleb Schneider AJ Pandey Nathaniel Barnett Samuel Wilson Gianmarco Scotti Thomas Piatkowski Josh Gonzalez Patrick Cascia Kolter Yagual-Ralston Guillermo Pineiro Kyle Casem Nicholas Casey Nathaniel Eck Ross Ferguson Sachin Boteju Mike Semancik Michael Munza Evan Dickonson Soroush Gharavi Jason Bedianko Colin Smith Benjamin Shanofsky . -

Warrant List-All Printed on August 30, 2021

Warrant List-All Printed on September 27, 2021 Date Issued Last, First Middle Name Age Last known Location State Warrant Type Bond Charges 09/09/21 ABDI, ABUBAKAR MOHAMED 24 MINNEAPOLIS MN Felony 10000.00 609.52.2(a)(4) - Theft-By Swindle 09/24/21 ABUKAR, IBRAHIM MOHAMED 24 MINNEAPOLIS MN Gross Misdemeanor Body Only 609.821.2(1) - Financial Transaction Card Fraud-Use-No Consent 05/26/21 ACOSTA, TOMAS ISRAEL 40 SAINT CLOUD MN Misdemeanor 50.00 (Bail) 171.24.1 - Traffic-Drivers License-Driving After Suspension 07/14/21 ADAMS, PAUL MICHAEL 39 SAUK RAPIDS MN Felony Body Only 152.025.2(1) - Drugs - 5th Degree - Possess Schedule 1,2,3,4 - Not Small Amount 03/24/21 AHMED, ABDIFATAH MOHAMED 27 MINNEAPOLIS MN Gross Misdemeanor Body Only 169A.20.1(1) - Traffic - DWI - Operate Motor Vehicle Under Influence of Alcohol 11/18/20 ALI, SEID ABDI 19 SAINT CLOUD MN Misdemeanor 100.00 (Bail) 609.52.2(a)(1) - Theft-Take/Use/Transfer Movable Prop-No Consent 08/18/21 ALLBRINK, ETHAN ELLIOTT 25 ELK RIVER MN Misdemeanor 300.00 (Bail) 609.72.1(1) - Disorderly Conduct - Brawling or Fighting 07/22/21 AMUNDSON, WILLIAM JOHN 46 ST CLOUD MN Misdemeanor 100.00 (Bail) 609.748.6(b) - Harassment; Restraining Order - Violate and knows of temporary or 07/01/21 ANDERSON, CHRISTOPHER 49 WATERTOWN MN Felony 30000.00 609.749.5(a) - Stalking - Engages in Stalking (F); 609.748.6(a) - Harassment; 07/01/21 ANDERSON, CHRISTOPHER 49 WATERTOWN MN Misdemeanor 10000.00 629.75.2(b) - Domestic Abuse No Contact Order - Violate No Contact Order - 07/01/21 ANDERSON, CHRISTOPHER 49 WATERTOWN -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

New Business Listing Print Date: 5/1/2019 Date Range: 04/01/2019 to 04/30/2019 Records Printed: 452

VIRGINIA BEACH New Business Listing Print Date: 5/1/2019 Date Range: 04/01/2019 to 04/30/2019 Records Printed: 452 ID Mont Year Owner Name Trade Name Address City State Zip Zip+4 Telephone h 14 2019 100% LLC TINT DADDYS 2841 VIRGINIA BEACH BLVD VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23452 7616 757-289-3321 24 2019 1ST LIGHT PRODUCTS LLC ROCK-IT SURF 2800 WOOD DUCK DR VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23456 4454 757-477-2729 34 2019 203 66TH STREET LLC 203 66TH STREET LLC 203 66TH ST VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23451 2040 757-321-4978 44 2019 4 SPICES MEDITERRANEAN FOOD LL 4 SPICES MEDITERRANEAN FOOD 1528 TAYLOR FARM RD STE 101 VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23453 0000 757-636-7783 54 2019 408 26TH ST LLC 408 26TH ST LLC 408 26TH ST VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23451 3117 540-722-2616 64 2019 636 16TH STREET LLC 636 16TH STREET LLC 636 16TH ST VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23451 4203 757-816-1169 74 2019 7 CITIES CAFE & GRILL LLC 7 CITIES CAFE & GRILL 2720 N MALL DR STE 160 VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23452 0000 757-416-4248 84 2019 7 ELEVEN INC 7 ELEVEN #39177 3673 VIRGINIA BEACH BLVD VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23452 3415 757-335-0392 94 2019 7 HILLS ADVISORS HAMPTON ROADS LLC 7 HILLS ADVISORS HAMPTON ROADS LLC 2404 POTTERS RD STE 600 VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23454 4335 757-647-3785 104 2019 7TH STREET NY PIZZA INC 7TH STREET NY PIZZA 712 ATLANTIC AVE VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23451 3526 757-236-2354 114 2019 A AND J TILE INSTALLATION LLC A AND J TILE INSTALLATION LLC 884 STRICKLAND BLVD VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23464 3944 757-752-7770 124 2019 A V ELECTRIC INCORPORATED A V ELECTRIC INCORPORATED 301 TERRACE AVE VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23451 3788 757-274-3940 134 -

St. Michael's Parish

ST. MICHAEL’S PARISH Weekend Mass Schedule Saturday: 4:00pm Sunday: English: 7:30am 9:00am 10:30am Portuguese: 10:30am Brazilian: 12:00pm Week Day Mass Schedule 9:00am Monday Wednesday, Friday and Saturday 7:00am Tuesday and Thurs- day Pastor: Rev. Ronald G. Calhoun Administrator: Very Rev. Marc Bishop, VF x301 [email protected] Xaverian Assistant: Rev. Anthony Lalli, S.X. Assistant: Rev. Adriano Albino de Castro [email protected] Finance & Operations Helena Siciliano x304 Manager: [email protected] Parish Nurse: Mary Ellen Bartlett [email protected] Religious Education Roz McHugh x309 Gr. K5: [email protected] Religious Education Brian Sousa x310 Gr. 6 Confirmation: [email protected] Custodians: Antonio Goncalves Francisco Pinheiro 21 Manning Street, Hudson, MA 01749 Phone: 9785622552 Fax: 9785681761 Religious Education Phone: 9785627662 www.stmikes.org @stmikes_hudson facebook.com/stmikes.hudson SǂNJǏǕ MNJDŽljǂdžǍ PǂǓNJǔlj Saturday December 23, 2017 4:00pm Murray “Skip” Buchanan If you have requested a Mass intention and would Sunday December 24, 2017 like to have a family member present the gifts, 7:30am Barbara & Catherine Gilroy please see a Extraordinary Minister of Holy Com- 9:00am Mr. & Mrs. Robert Milliken munion before the start of the Mass. 10:30am St. Michael Parishioners 10:30am Mensageiros de Fatima 12:00pm Brazilian Mass Inclement Weather Notice If there is a delay or cancellation at the Hudson Sunday Christmas Eve Public Schools due to inclement weather, the daily 4:00pm 4:00pm St. Michael Parishioners Mass is canceled! 6:00pm Monday December 25, 2017 8:00am For St. Michael Parishioners 10:30am For St. -

Cata Resume Sept 2015

Cat Rendic SAGAFTRA TELEVISION/FILM LIP SYNC BATTLE season 1 Dancer Danielle Flora NBA Allstar Game 2015 Christina Aguilera Dancer Jeri Slaughter, Paul Morente Miss Universe Nick Jonas Dancer Casper Smart, Kevin Maher A Step Away Docu Series. Entire Season. Main Character NUVO TV. Jennifer Lopez Nicki Minaj iHeartRadio, Emas, Fashion Rocks Dancer Casper Smart Pitbull Chris Brown Wisin Latin Grammys Dancer/Assistant Choreo Anibal Marrero Jessie J Halo Awards, NNNAwards Dancer Casper Smart The Voice, Gwen Stefani and Pharrell Dancer Jeri Slaughter/Fatima Robinson Ellen Degeneres Show with Julianne and Derek Hough Dancer Nappytabs XFactor season 3 Dancer Jamie King, Galen Hooks American Idol “Carly Rae Jepsen” Dancer Nick Demoura/Kevin Maher Super Bowl Half Time Show Beyonce/Destiny’s Child Dancer F. Gatson/Jaquel Knight/Chris Grant American Idol Jennifer Lopez Dancer Nappytabs NBA Allstar Pitbull, Neyo, Chris Brown Dancer Anibal Marrero/Jamaica Craft Dancing with the Stars with Pitbull Dancer/asst Anibal Marrero Britney Spears Jimmy Kimmel, GMA, MTV PROMO Dancer Jamie King/Brian Friedman Sing Your Face Off Season 1 Dancer Nappytabs Academy Awards with Ann Hathaway and James Franco Dancer Jamal Sims/Draico Johnson Home For The Holidays w. Ricky Martin Dancer Stephanie Roos Fresh Beat Band “Halloween, Graduation, Victorious” Dancer Chuck Maldonado/Nickelodeon Glee “Britney/Brittany” “Hairography” Dancer Zach Woodle/Brooke Lipton/FOX America’s Got Talent Eps 527 Dancer B.Friedman,C. Dupre, Oprah w/ Christina Aguilera Dancer Jeri Slaughter