The Zoramites and Costly Apparel: Symbolism and Irony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Name Zoram and Its Paronomastic Pejoration

“See That Ye Are Not Lifted Up”: The Name Zoram and Its Matthew L. Bowen [Page 109]Abstract: The most likely etymology for the name Zoram is a third person singular perfect qal or pô?al form of the Semitic/Hebrew verb *zrm, with the meaning, “He [God] has [is] poured forth in floods.” However, the name could also have been heard and interpreted as a theophoric –r?m name, of which there are many in the biblical Hebrew onomasticon (Ram, Abram, Abiram, Joram/Jehoram, Malchiram, etc., cf. Hiram [Hyrum]/Huram). So analyzed, Zoram would connote something like “the one who is high,” “the one who is exalted” or even “the person of the Exalted One [or high place].” This has important implications for the pejoration of the name Zoram and its gentilic derivative Zoramites in Alma’s and Mormon’s account of the Zoramite apostasy and the attempts made to rectify it in Alma 31–35 (cf. Alma 38–39). The Rameumptom is also described as a high “stand” or “a place for standing, high above the head” (Heb. r?m; Alma 31:13) — not unlike the “great and spacious building” (which “stood as it were in the air, high above the earth”; see 1 Nephi 8:26) — which suggests a double wordplay on the name “Zoram” in terms of r?m and Rameumptom in Alma 31. Moreover, Alma plays on the idea of Zoramites as those being “high” or “lifted up” when counseling his son Shiblon to avoid being like the Zoramites and replicating the mistakes of his brother Corianton (Alma 38:3-5, 11-14). -

How Were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related?

KnoWhy #109 May 27, 2016 Battle with Zeniff . Artwork by James Fullmer How were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related? “Now the people of Amlici were distinguished by the name of Amlici, being called Amlicites” Alma 2:11 The Know Only five years into the reign of the judges, the pres- with no introduction or explanation as to their ori- sure to reestablish a king was already mounting. A gins (Alma 21:2–4, 16).3 Later they are included in a “certain man, being called Amlici,” emerged, and list of Nephite dissenters (Alma 43:13), but this is all he drew “away much people after him” who “be- that is said of their origins. gan to endeavor to establish Amlici to be a king over the people” (Alma 2:1–2). When “the voice of The complete disappearance of the Amlicites, com- people” failed to grant kingship to Amlici,1 his fol- bined with the mysterious mention of the similarly lowers anointed him king anyway, and they broke named Amalekites, has led some scholars to con- away from the Nephites, becoming Amlicites (Alma clude that the two groups are one and the same.4 As 2:7–11). Christopher Conkling observed, “One group is in- troduced as if it will have ongoing importance. The The rebellion of the Amlicites led to armed conflict other is first mentioned as if its identity has already with the Nephites (Alma 2:10–20), and then an al- been established.”5 legiance with the Lamanites, followed by further bloodshed, wherein Amlici was slain in one-on-one Royal Skousen has found evidence from the original combat with Alma (Alma 2:21–38). -

The River Sidon

The River Sidon A Key to Unlocking Book of Mormon Lands Lynn and David Rosenvall, November 2010 Alma baptized in its waters. Armies crossed it multiple times in a single battle. Hills and valleys flanked its banks. The cities of Zarahemla and Gideon were positioned on opposite sides of its course. Two groups—the people of Nephi and the people of Zarahemla (the Mulekites)—shared its basin. A third group—the Lamanites—often invaded its Narrow borders and attempted to move north for their own Neck of strategic reasons. The dead from the resulting wars were Land unceremoniously thrown into its waters. Nearby wilderness areas provided hiding places for the Gadianton robbers to swoop down and plunder in its lowlands. And the final Zarahemla battles leading to the demise of the Lamanite and Nephite civilizations began near its edge and ended at Cumorah. All Sea Sea West River Sidon East this and more took place along the river Sidon—the river that is central to the Book of Mormon story and a key to Narrow the Book of Mormon geography. Strip of Wilderness The river Sidon is the only named river in Mormon’s Nephi abridgment of the Nephite record. And there is only one watercourse within the heartlands of the peninsula of Baja California that could be considered the river Sidon—the Rio San Ignacio. Within minutes of our initial scrutiny of Baja California as a promising location for the Book of Mormon N lands, we became cautiously aware we had only one candidate river. Impressively, this one river is located where The river Sidon (Rio San Ignacio) in the river Sidon needs to be situated—between the area on the center of Baja California. -

The Witness of the King and Queen Astonished the Specta- Jesus According to His Timing

Published Quarterly by The Book of Mormon Foundation Number 119 • Summer 2006 Now the people which were not Lamanites, were Nephites; nevertheless, they were called Nephites, Jacobites, Josephites, Zoramites, Lamanites, Lemuelites, and Ishmaelites. But I, Jacob, shall not hereafter Sam, the Son distinguish them by these names, but I shall call them Lamanites, that seek to destroy the people of Nephi; and those who are friendly to Nephi, I shall call Nephites, or the people of Nephi, according to the reigns of the kings. (Jacob 1:13-14; see also 4 Nephi 1:40-42; of Lehi Mormon 1:8 RLDS) [Jacob 1:13-14, see also 4 Nephi by Gary Whiting 1:36-38, Mormon 1:8 LDS] he opening pages of the Book of Mormon describe Each of the sons of Lehi had families that developed the faith and struggles of the prophet Lehi as seen into tribes known by the name of the son who fathered them. T through the eyes of his son, Nephi. Nephi describes Thus the tribal names were Lamanites, Lemuelites, Nephites, his family’s departure from Jerusalem and the trial of their long Jacobites and Josephites. Even Zoram (Zoramites) and Ishmael journey to the Promised Land. Through the pages of Nephi’s (Ishmaelites) had their names attached to tribal families. spiritual journey, the family and friends of Lehi are introduced. However, never in the Book of Mormon is a tribe named As the story begins, Lehi has four sons: Laman, Lemuel, Sam after Sam. Why is this? and Nephi. The first introduction of the family is given by Although he is somewhat of a mystery, Sam’s life and faith Nephi shortly after they left the land of Jerusalem. -

Moroni's Title of Liberty

ZARAHEMLA REC lssue45 .|989 TheMeanirg Behind November Moroni'sTitle of Liberty by David Lamb \-/ ne of the greatest insights es- gain the advantage. Only by con- it is safeto assumethat Moroni was sential to understanding the scrip- stantly looking to the rod which well versedin the word of God and tures can be found in 2 Nephi 8:9: Moses holds up do the Israelites the usageof types and shadows. In "And all things which have been prevail and become victorious over fact, it is highly possiblethat given of God from the beginning of their adversary. Moroni's idea for the title of liberty the world, unto man, are the typlfy- The key to understanding the was the result of his familiarity with ing of him" (lesus Christ). Simply symbolism in this account is found the Jehovah-Nissiaccount. stated, God has placed a pattern in in verse 15 as Moses builds an altar To understandthe symbolism all things, and all things bear witness to commemorate the event and calls associatedwith the title of liberty, it of JesusChrist that we might not be the altar IEHOVAH-NISSI, which is necessaryto realizethat physical deceived. Time after time, God translated means THE LORD IS MY warfare, as depicted in the scrip- reveals this pattern through the BANNER. The Hebrew word nissi tures, is symbolic of spiritual war- means of types and shadows. This may equally be translated as "stan- fare. Satanand his followers con- use of symbolism reminds us that dard," "ensign," or "pole," as well as stantly seekto attack (makewar Jesusis the only one to whom we are "banner." The insight to be gained against)that which belongsto God, to look for eternal salvation and from this event is that only by contendingfor the very souls of deliverance from death and hell. -

The Amlicites and Amalekites

The Amlicites and Amalekites: Are They the Same People? Benjamin McMurtry [Page 269]Abstract: Royal Skousen’s Book of Mormon Critical Text Project has proposed many hundreds of changes to the text of the Book of Mormon. A subset of these changes does not come from definitive evidence found in the manuscripts or printed editions but are conjectural emendations. In this paper, I examine one of these proposed changes — the merging of two dissenting Nephite groups, the Amlicites and the Amalekites. Carefully examining the timeline and geography of these groups shows logical problems with their being the same people. This paper argues that they are, indeed, separate groups and explores a plausible explanation for the missing origins of the Amalekites. In the landmark Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, Royal Skousen endeavored to restore the original reading of the Book of Mormon. By examining the manuscripts and earliest printed editions of the Book of Mormon, he discovered and corrected hundreds of errors. There are instances where an appeal to the original texts did not yield a conclusive result, however. In such cases, Skousen chose to create a new reading based on his conjectural emendation.1 There are many such conjectural emendations in his Earliest Text,2 but perhaps the one that has had the greatest potential impact on how we understand the story of the Book of Mormon is the decision to change every instance of Amalekite(s) to Amlicite(s). In the four-page explanation3 that Skousen gave on the subject, he offers spelling and narrative reasons for and against merging the two groups. -

Religion of the Nehors

Book of Mormon Central http ://bookofmormoncentral.org/ s Type: Excerpt Excursus:Second Religion Witness, Analytical of the & NehorsContextual Commentary on the Book of Author(s): Mormon: Brant VolumeA. Gardner 4, Alma Source: Published: Salt Lake City; Greg Kofford Books, 2007 Page(s): 41–51 Abstract: The book of Alma begins with religious conflict and, by the end, escalates into military conflict. Mormon saw the later wars as the direct result of the early religious dissensions, which led not just to disagreement but to defection. The worst conflicts with “Lamanites” are not with those had always been Lamanites, but with apostate Nephites who became Lamanites. Mormon saw internal contention and religio-political fission as the cause of the Nephites’ virtual destruction before the Messiah came to Bountiful. Alma2 apparently saw the same problem and attempted to heal the social rifts by religious renewal. Greg Kofford Books is collaborating with Book of Mormon Central to preserve and extend access to scholarly research on The Book of Mormon. This excerpt was archived by permission of Greg Kofford Books. https://gregkofford.com/ Excursus: Religion of the Nehors he book of Alma begins with religious conflict and, by the end, escalates into military conflict. Mormon saw the later wars as the direct result of the early T religious dissensions, which led not just to disagreement but to defection. The worst conflicts with “Lamanites” are not with those had always been Lamanites, but with apostate Nephites who became Lamanites. Mormon saw internal contention and religio-political fission as the cause of the Nephites’ virtual destruction before the Messiah came to Bountiful. -

Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching John W

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 1999 Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching John W. Welch J. Gregory Welch Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Welch, John W. and Welch, J. Gregory, "Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching" (1999). Maxwell Institute Publications. 20. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Charting the Book of Mormon FARMS Publications Teachings of the Book of Mormon Copublished with Deseret Book Company The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon The Book of Mormon Text Reformatted according to Warfare in the Book of Mormon Parallelistic Patterns By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh Eldin Ricks’s Thorough Concordance of the LDS W. Nibley Standard Works The Sermon at the Temple and the Sermon on the A Guide to Publications on the Book of Mormon: A Mount Selected Annotated Bibliography Rediscovering the Book of Mormon Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence Reexploring the Book of Mormon for Ancient Origins Of All Things! Classic Quotations from Hugh -

Table of Contents Hook Dates of the Book of Mormon Volume 2

Table of Contents Hook Dates of the Book of Mormon Volume 2 Hook Date Review Page 3 64 B.C – Helaman – 2,000 Faithful Sons Page 5 - 0 - Nephi the Third - Christ's Birth Page 35 A.D. 34 – Jesus Christ – Savior Visits America page 61 A.D. 333 – Mormon – A Fallen People Page 89 A.D. 421 – Moroni – Plates of Gold Hidden Page 111 Appendix Page 135 The Book of Mormon is Amazing! Page 136 Precious Truths in the Book of Mormon Page 137 Hebrew & English Compared Page 139 Who Was Melchizedek? Page 140 The Famous Prophet Isaiah Page 150 Who are the Gadiantons Today? Page 158 Hagoth’s Possible Route – Map Page 166 The Polynesians Page 167 The Law of Consecration & Order of Enoch Page 183 Answer Key Page 195 Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 1 (Review) The Ten Hook-Dates with Key Personalities and Key Events 2200 B.C. Brother of Jared Tower of Babel 600 B.C. Lehi and Mulek Journeys to America 130 B.C. Mosiah & Benjamin A Covenant People 90 B.C. Alma Missionary Work 73 B.C. Captain Moroni Title of Liberty 64 B.C. Helaman 2,000 Faithful Sons - 0 - Nephi III Christ’s Birth A.D. 34 Jesus Christ Savior Visits America A.D. 333 Mormon A Fallen People A.D. 421 Moroni Plates of Gold Hidden Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 2 Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 3 Summarizing 64 B.C – Helaman – 2,000 Faithful Sons (Comprising Alma Chapter 56 through Helaman Chapter 6) 1. -

Alma's Enemies: the Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 14 Number 1 Article 12 1-31-2005 Alma's Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites J. Christopher Conkling University of Judaism in Bel-Air, California Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Conkling, J. Christopher (2005) "Alma's Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 14 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol14/iss1/12 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Alma’s Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites Author(s) J. Christopher Conkling Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14/1 (2005): 108–17, 130–32. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In Alma 21 a new group of troublemakers is intro- duced—the Amalekites—without explanation or introduction. This article offers arguments that this is the same group called Amlicites elsewhere and that the confusion is caused by Oliver Cowdery’s incon- sistency in spelling. If this theory is accurate, then Alma structured his narrative record more tightly and carefully than previously realized. The concept also challenges the simplicity of the good Nephite/bad Lamanite rubric so often used to describe the players in the book of Mormon. -

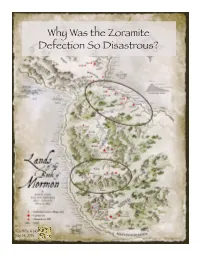

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous?

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous? KnoWhy #143 July 14, 2016 And thus the Zoramites and the Lamanites began to make preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also against the Nephites. Alma 35:11 The Know At the end of Alma 30, the Book of Mormon reports that a group phets, and in consequence were geographically and politically of Nephite dissenters, known as the Zoramites,1 were responsible caught between two major world powers—the Egyptians to the for Korihor’s death (Alma 30:59).2 After receiving news that “the south and the Babylonians to the north. Acting out of fear, and in Zoramites were perverting the ways of the Lord,”3 Alma gathered direct defiance of Jeremiah’s prophetic counsel, King Zedekiah an elite group of missionaries to “preach unto them the word of chose to ally Israel with Egypt.7 This poor decision eventually led God” (Alma 31:1, 7). Yet despite efforts to reclaim these apos- to a Babylonian invasion, which ended with Zedekiah being exiled tates, the Zoramites “cast out of the land” any who believed in the into Babylon after the execution of his family.8 words of Alma and Amulek (Alma 35:6). The Zoramite problem immediately escalated into a series of all-out wars in the land of The Why Zarahemla. Like the kingdom of Judah in Lehi’s time, the Nephites were vul- nerable to enemy incursions on two separate fronts. Understand- When the people of Ammon took in these exiled believers, the ing the high stakes that were involved in this situation—meaning Zoramites stirred up the Lamanites to anger, and together they both the worth of souls among the Zoramites as well as the need made “preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also to maintain them as military allies—can help readers better em- against the Nephites” (Alma 35:11). -

THE ADOPTION of BIBLICAL ARCHAISMS in the BOOK of MORMON and OTHER 19TH CENTURY TEXTS by Gregory A

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Sounding sacred: The dopta ion of biblical archaisms in the Book of Mormon and other 19th century texts Gregory A. Bowen Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Bowen, Gregory A., "Sounding sacred: The dopta ion of biblical archaisms in the Book of Mormon and other 19th century texts" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 945. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/945 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. SOUNDING SACRED: THE ADOPTION OF BIBLICAL ARCHAISMS IN THE BOOK OF MORMON AND OTHER 19TH CENTURY TEXTS by Gregory A. Bowen A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics West Lafayette, Indiana December 2016 ii THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL Dr. Mary Niepokuj, Chair Department of English Dr. Shaun Hughes Department of English Dr. John Sundquist Department of Linguistics Dr. Atsushi Fukada Department of Linguistics Approved by: Dr. Alejandro Cuza-Blanco Head of the Departmental Graduate Program iii For my father iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee for all they have done to make this project possible, especially my advisor, Dr. Mary Niepokuj, who tirelessly provided guidance and encouragement, and has been a fantastic example of what a teacher should be.