The Amlicites and Amalekites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Name Zoram and Its Paronomastic Pejoration

“See That Ye Are Not Lifted Up”: The Name Zoram and Its Matthew L. Bowen [Page 109]Abstract: The most likely etymology for the name Zoram is a third person singular perfect qal or pô?al form of the Semitic/Hebrew verb *zrm, with the meaning, “He [God] has [is] poured forth in floods.” However, the name could also have been heard and interpreted as a theophoric –r?m name, of which there are many in the biblical Hebrew onomasticon (Ram, Abram, Abiram, Joram/Jehoram, Malchiram, etc., cf. Hiram [Hyrum]/Huram). So analyzed, Zoram would connote something like “the one who is high,” “the one who is exalted” or even “the person of the Exalted One [or high place].” This has important implications for the pejoration of the name Zoram and its gentilic derivative Zoramites in Alma’s and Mormon’s account of the Zoramite apostasy and the attempts made to rectify it in Alma 31–35 (cf. Alma 38–39). The Rameumptom is also described as a high “stand” or “a place for standing, high above the head” (Heb. r?m; Alma 31:13) — not unlike the “great and spacious building” (which “stood as it were in the air, high above the earth”; see 1 Nephi 8:26) — which suggests a double wordplay on the name “Zoram” in terms of r?m and Rameumptom in Alma 31. Moreover, Alma plays on the idea of Zoramites as those being “high” or “lifted up” when counseling his son Shiblon to avoid being like the Zoramites and replicating the mistakes of his brother Corianton (Alma 38:3-5, 11-14). -

How Were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related?

KnoWhy #109 May 27, 2016 Battle with Zeniff . Artwork by James Fullmer How were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related? “Now the people of Amlici were distinguished by the name of Amlici, being called Amlicites” Alma 2:11 The Know Only five years into the reign of the judges, the pres- with no introduction or explanation as to their ori- sure to reestablish a king was already mounting. A gins (Alma 21:2–4, 16).3 Later they are included in a “certain man, being called Amlici,” emerged, and list of Nephite dissenters (Alma 43:13), but this is all he drew “away much people after him” who “be- that is said of their origins. gan to endeavor to establish Amlici to be a king over the people” (Alma 2:1–2). When “the voice of The complete disappearance of the Amlicites, com- people” failed to grant kingship to Amlici,1 his fol- bined with the mysterious mention of the similarly lowers anointed him king anyway, and they broke named Amalekites, has led some scholars to con- away from the Nephites, becoming Amlicites (Alma clude that the two groups are one and the same.4 As 2:7–11). Christopher Conkling observed, “One group is in- troduced as if it will have ongoing importance. The The rebellion of the Amlicites led to armed conflict other is first mentioned as if its identity has already with the Nephites (Alma 2:10–20), and then an al- been established.”5 legiance with the Lamanites, followed by further bloodshed, wherein Amlici was slain in one-on-one Royal Skousen has found evidence from the original combat with Alma (Alma 2:21–38). -

“Converted Unto the Lord”

HIDDEN LDS/JEWISH INSIGHTS - Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Supplement #26 by Daniel Rona Summary Handout =========================================================================================================== “Converted unto the Lord” Lesson 26 Summary Alma 23– 29 =========================================================================================================== Scripture Religious freedom is proclaimed—The Lamanites in seven lands and cities are converted—They call themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehies and Summary: are freed from the curse—The Amalekites and the Amulonites reject the truth. The Lamanites come against the people of God—The Anti-Nephi-Lehies rejoice in Christ and are visited by angels—They choose to suffer death rather than to defend themselves—More Lamanites are converted. Lamanite aggressions spread—The seed of the priests of Noah perish as Abinadi prophesied—Many Lamanites are converted and join the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi—They believe in Christ and keep the law of Moses. Ammon glories in the Lord—The faithful are strengthened by the Lord and are given knowledge—By faith men may bring thousands of souls unto repentance—God has all power and comprehendeth all things. The Lord commands Ammon to lead the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi to safety—Upon meeting Alma, Ammon’s joy exhausts his strength—The Nephites give them the land of Jershon— They are called the people of Ammon. [Between 90 and 77 B.C.] The Lamanites are defeated in a tremendous battle—Tens of thousands are slain—The wicked are consigned to a state of endless woe; the righteous attain a never-ending happiness. [About 76 B.C.] Alma desires to cry repentance with angelic zeal—The Lord grants teachers for all nations—Alma glories in the Lord’s work and in the success of Ammon and his brethren. -

EVIDENCE of the NEHOR RELIGION in MESOAMERICA

EVIDENCE of the NEHOR RELIGION in MESOAMERICA Jerry D. Grover Jr., PE, PG Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica by Jerry D. Grover, Jr. PE, PG Jerry D. Grover, Jr., is a licensed Professional Structural and Civil Engineer and a licensed Professional Geologist. He has an undergraduate degree in Geological Engineering from BYU and a Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Utah. He speaks Italian and Chinese and has worked with his wife as a freelance translator over the past 25 years. He has provided geotechnical and civil engineering design for many private and public works projects. He took a 12-year hiatus from the sciences and served as a Utah County Commissioner from 1995 to 2007. He is currently employed as the site engineer for the remediation and redevelopment of the 1750-acre Geneva Steel site in Vineyard, Utah. He has published numerous scientific and linguistic books centering on the Book of Mormon, all of which are available for free in electronic format at www.bmslr.org. Acknowledgments: This book is dedicated to my gregarious daughter, Shirley Grover Calderon, and her wonderful husband Marvin Calderon and his family who are of Mayan descent. Thanks are due to Sandra Thorne for her excellent editing, and to Don Bradley and Dr. Allen Christenson for their thorough reviews and comments. Peer Review: This book has undergone third-party blind review and third-party open review without distinction as to religious affiliation. As with all of my works, it will be available for free in electronic format on the open web, so hopefully there will be ongoing peer review in the form of book reviews, etc. -

Religion of the Nehors

Book of Mormon Central http ://bookofmormoncentral.org/ s Type: Excerpt Excursus:Second Religion Witness, Analytical of the & NehorsContextual Commentary on the Book of Author(s): Mormon: Brant VolumeA. Gardner 4, Alma Source: Published: Salt Lake City; Greg Kofford Books, 2007 Page(s): 41–51 Abstract: The book of Alma begins with religious conflict and, by the end, escalates into military conflict. Mormon saw the later wars as the direct result of the early religious dissensions, which led not just to disagreement but to defection. The worst conflicts with “Lamanites” are not with those had always been Lamanites, but with apostate Nephites who became Lamanites. Mormon saw internal contention and religio-political fission as the cause of the Nephites’ virtual destruction before the Messiah came to Bountiful. Alma2 apparently saw the same problem and attempted to heal the social rifts by religious renewal. Greg Kofford Books is collaborating with Book of Mormon Central to preserve and extend access to scholarly research on The Book of Mormon. This excerpt was archived by permission of Greg Kofford Books. https://gregkofford.com/ Excursus: Religion of the Nehors he book of Alma begins with religious conflict and, by the end, escalates into military conflict. Mormon saw the later wars as the direct result of the early T religious dissensions, which led not just to disagreement but to defection. The worst conflicts with “Lamanites” are not with those had always been Lamanites, but with apostate Nephites who became Lamanites. Mormon saw internal contention and religio-political fission as the cause of the Nephites’ virtual destruction before the Messiah came to Bountiful. -

Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching John W

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 1999 Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching John W. Welch J. Gregory Welch Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Welch, John W. and Welch, J. Gregory, "Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching" (1999). Maxwell Institute Publications. 20. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Charting the Book of Mormon FARMS Publications Teachings of the Book of Mormon Copublished with Deseret Book Company The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon The Book of Mormon Text Reformatted according to Warfare in the Book of Mormon Parallelistic Patterns By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh Eldin Ricks’s Thorough Concordance of the LDS W. Nibley Standard Works The Sermon at the Temple and the Sermon on the A Guide to Publications on the Book of Mormon: A Mount Selected Annotated Bibliography Rediscovering the Book of Mormon Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence Reexploring the Book of Mormon for Ancient Origins Of All Things! Classic Quotations from Hugh -

The Book of Mosiah: Thoughts About Its Structure, Purposes, Themes, and Authorship

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Article 5 7-31-1995 The Book of Mosiah: Thoughts about Its Structure, Purposes, Themes, and Authorship Gary L. Sturgess Sturgess Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sturgess, Gary L. (1995) "The Book of Mosiah: Thoughts about Its Structure, Purposes, Themes, and Authorship," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 4 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol4/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title The Book of Mosiah: Thoughts about Its Structure, Purposes, Themes, and Authorship Author(s) Gary L. Sturgess Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4/2 (1995): 107–35. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract The book of Mosiah is a cultic history of the reign of Mosiah2, structured around three royal ceremonies in 124, 121, and 92–91 bc. On each of these occasions, newly discovered scriptures were read to the people, stressing the dangers of monarchical government and celebrating the deliverance of the people and the revela- tion of Jesus Christ. This book existed independently hundreds of years before Mormon engraved it onto the gold plates. The most likely occasion for the writ- ing of such a book was in the aftermath of Mosiah’s death when Alma the Younger needed to undermine the Amlicite bid to reestablish the monarchy. -

Table of Contents Hook Dates of the Book of Mormon Volume 2

Table of Contents Hook Dates of the Book of Mormon Volume 2 Hook Date Review Page 3 64 B.C – Helaman – 2,000 Faithful Sons Page 5 - 0 - Nephi the Third - Christ's Birth Page 35 A.D. 34 – Jesus Christ – Savior Visits America page 61 A.D. 333 – Mormon – A Fallen People Page 89 A.D. 421 – Moroni – Plates of Gold Hidden Page 111 Appendix Page 135 The Book of Mormon is Amazing! Page 136 Precious Truths in the Book of Mormon Page 137 Hebrew & English Compared Page 139 Who Was Melchizedek? Page 140 The Famous Prophet Isaiah Page 150 Who are the Gadiantons Today? Page 158 Hagoth’s Possible Route – Map Page 166 The Polynesians Page 167 The Law of Consecration & Order of Enoch Page 183 Answer Key Page 195 Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 1 (Review) The Ten Hook-Dates with Key Personalities and Key Events 2200 B.C. Brother of Jared Tower of Babel 600 B.C. Lehi and Mulek Journeys to America 130 B.C. Mosiah & Benjamin A Covenant People 90 B.C. Alma Missionary Work 73 B.C. Captain Moroni Title of Liberty 64 B.C. Helaman 2,000 Faithful Sons - 0 - Nephi III Christ’s Birth A.D. 34 Jesus Christ Savior Visits America A.D. 333 Mormon A Fallen People A.D. 421 Moroni Plates of Gold Hidden Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 2 Study of the Book of Mormon, Volume 2 – Page 3 Summarizing 64 B.C – Helaman – 2,000 Faithful Sons (Comprising Alma Chapter 56 through Helaman Chapter 6) 1. -

Peoples of the Book of Mormon

Peoples of the Book of Mormon John L. Sorenson At least fteen distinct groups of people are mentioned in the Book of Mormon. Four (Nephites, Lamanites, Jaredites, and the people of Zarahemla [Mulekites]) played a primary role; ve were of secondary concern; and six more were tertiary elements. Nephites. The core of this group were direct descendants of Nephi1, the son of founding father Lehi. Political leadership within the Nephite wing of the colony was “conferred upon none but those who were descendants of Nephi” (Mosiah 25:13). Not only the early kings and judges but even the last military commander of the Nephites, Mormon, qualied in this regard (he explicitly notes that he was “a pure descendant of Lehi” [3 Ne. 5:20] and “a descendant of Nephi” [Morm. 1:5]). In a broader sense, “Nephites” was a label given all those governed by a Nephite ruler, as in Jacob 1:13 : “The people which were not Lamanites were Nephites; nevertheless, they were called [when specied according to descent] Nephites, Jacobites, Josephites, Zoramites, Lamanites, Lemuelites, and Ishmaelites.” It is interesting to note that groups without direct ancestral connections could come under the Nephite sociopolitical umbrella. Thus, “all the people of Zarahemla were numbered with the Nephites” (Mosiah 25:13). This process of political amalgamation had kinship overtones in many instances, as when a body of converted Lamanites “took upon themselves the name of Nephi, that they might be called the children of Nephi and be numbered among those who were called Nephites” (Mosiah 25:12). The odd phrase “the people of the Nephites” in such places as Alma 54:14 and Helaman 1:1 suggests a social structure where possibly varied populations (“the people”) were controlled by an elite (“the Nephites”). -

Alma's Enemies: the Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 14 Number 1 Article 12 1-31-2005 Alma's Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites J. Christopher Conkling University of Judaism in Bel-Air, California Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Conkling, J. Christopher (2005) "Alma's Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 14 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol14/iss1/12 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Alma’s Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites Author(s) J. Christopher Conkling Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14/1 (2005): 108–17, 130–32. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In Alma 21 a new group of troublemakers is intro- duced—the Amalekites—without explanation or introduction. This article offers arguments that this is the same group called Amlicites elsewhere and that the confusion is caused by Oliver Cowdery’s incon- sistency in spelling. If this theory is accurate, then Alma structured his narrative record more tightly and carefully than previously realized. The concept also challenges the simplicity of the good Nephite/bad Lamanite rubric so often used to describe the players in the book of Mormon. -

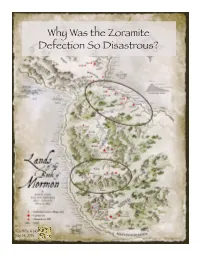

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous?

Why Was the Zoramite Defection So Disastrous? KnoWhy #143 July 14, 2016 And thus the Zoramites and the Lamanites began to make preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also against the Nephites. Alma 35:11 The Know At the end of Alma 30, the Book of Mormon reports that a group phets, and in consequence were geographically and politically of Nephite dissenters, known as the Zoramites,1 were responsible caught between two major world powers—the Egyptians to the for Korihor’s death (Alma 30:59).2 After receiving news that “the south and the Babylonians to the north. Acting out of fear, and in Zoramites were perverting the ways of the Lord,”3 Alma gathered direct defiance of Jeremiah’s prophetic counsel, King Zedekiah an elite group of missionaries to “preach unto them the word of chose to ally Israel with Egypt.7 This poor decision eventually led God” (Alma 31:1, 7). Yet despite efforts to reclaim these apos- to a Babylonian invasion, which ended with Zedekiah being exiled tates, the Zoramites “cast out of the land” any who believed in the into Babylon after the execution of his family.8 words of Alma and Amulek (Alma 35:6). The Zoramite problem immediately escalated into a series of all-out wars in the land of The Why Zarahemla. Like the kingdom of Judah in Lehi’s time, the Nephites were vul- nerable to enemy incursions on two separate fronts. Understand- When the people of Ammon took in these exiled believers, the ing the high stakes that were involved in this situation—meaning Zoramites stirred up the Lamanites to anger, and together they both the worth of souls among the Zoramites as well as the need made “preparations for war against the people of Ammon, and also to maintain them as military allies—can help readers better em- against the Nephites” (Alma 35:11). -

THE ADOPTION of BIBLICAL ARCHAISMS in the BOOK of MORMON and OTHER 19TH CENTURY TEXTS by Gregory A

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Sounding sacred: The dopta ion of biblical archaisms in the Book of Mormon and other 19th century texts Gregory A. Bowen Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Bowen, Gregory A., "Sounding sacred: The dopta ion of biblical archaisms in the Book of Mormon and other 19th century texts" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 945. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/945 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. SOUNDING SACRED: THE ADOPTION OF BIBLICAL ARCHAISMS IN THE BOOK OF MORMON AND OTHER 19TH CENTURY TEXTS by Gregory A. Bowen A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics West Lafayette, Indiana December 2016 ii THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL Dr. Mary Niepokuj, Chair Department of English Dr. Shaun Hughes Department of English Dr. John Sundquist Department of Linguistics Dr. Atsushi Fukada Department of Linguistics Approved by: Dr. Alejandro Cuza-Blanco Head of the Departmental Graduate Program iii For my father iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee for all they have done to make this project possible, especially my advisor, Dr. Mary Niepokuj, who tirelessly provided guidance and encouragement, and has been a fantastic example of what a teacher should be.