Asian American Voting During the 2020 Elections: a Rising, Divided Voting Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

418GBJ Web.Pdf

April 2018 Volume 23, Number 6 From the Executive GEORGIA BAR Director: Website and Directory Enhancements to Benefit Bar Members and the Public Financial Institutions: JOURNAL Protecting Elderly Clients From Financial Exploitation Bending the Arc: Georgia Lawyers in the Pursuit of Social Justice Writing Matters: What e-Filing May Mean to Your Writing 2018 ANNUAL MEETING Amelia Island, Fla. | June 7-10 GEORGIA LAWYERS HELPING LAWYERS Georgia Lawyers Helping Lawyers (LHL) is a new confidential peer-to-peer program that will provide u colleagues who are suffering from stress, depression, addiction or other personal issues in their lives, with a fellow Bar member to be there, listen and help. The program is seeking not only peer volunteers who have experienced particular mental health or substance use u issues, but also those who have experience helping others or just have an interest in extending a helping hand. For more information, visit: www.GeorgiaLHL.org ADMINISTERED BY: DO YOUR EMPLOYEE BENEFITS ADD UP? Finding the right benets provider doesn’t have to be a calculated risk. Our oerings range from Health Coverage to Disability and everything in between. Through us, your rm will have access to unique cost savings opportunities, enrollment technology, HR Tools, and more! The Private Insurance Exchange + Your Firm = Success START SHOPPING THE PRIVATE INSURANCE EXCHANGE TODAY! www.memberbenets.com/gabar OR CALL (800) 282-8626 APRIL 2018 HEADQUARTERS COASTAL GEORGIA OFFICE SOUTH GEORGIA OFFICE 104 Marietta St. NW, Suite 100 18 E. Bay St. 244 E. Second St. (31794) Atlanta, GA 30303 Savannah, GA 31401-1225 P.O. -

Meeting Agenda

LAS VIRGENES – MALIBU COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS GOVERNING BOARD MEETING Tuesday, April 20, 2021, 8:30 AM MEETING INFORMATION AND ACCOMMODATION Pursuant to the Governor’s Executive Orders, which waived certain Brown Act meeting requirements, including any requirements to make a physical meeting location available to the public; and, most recently, the March 19, 2020 Executive Order, which ordered all residents to stay at home. As such, the Las Virgenes-Malibu Council of Governments will provide Members of the Public the opportunity to view and participate in the meeting remotely using Zoom: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/4714103699?pwd=WFVESXV3Q1ROVW5kVThBVHdvZDJlQT09 Meeting ID: 471 410 3699 - Passcode: 1234 A public agenda packet is available on the COG’s website lvmcog.org. Members of the Public who wish to comment on matters before the Governing Board have two options: 1. Make comments limited to three minutes during the Public Comment Period, or 2. Submit an email with their written comments limited to 1,000 characters to [email protected] no later than 12:00 p.m. on Monday, April 19, 2021. The email address will remain open during the meeting for providing public comment during the meeting. Emails received during the meeting will be read out loud at the appropriate time during the meeting provided they are received before the Board takes action on an item (or can be read during general public comment). For any questions regarding the virtual meeting, please contact [email protected]. AGENDA 1. CALL TO ORDER Roll Call of Governing Board Members: Kelly Honig, Westlake Village, President Karen Farrer, Malibu, Vice President Stuart Siegel, Hidden Hills Denis Weber, Agoura Hills Alicia Weintraub, Calabasas 2. -

Measuring Impact of New Obstacles on Minority Voter Registration

Legal Dodges and Subterfuges: Measuring Impact of New Obstacles on Minority Voter Registration Jennifer Ann Hitchcock Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Political Science Nicholas Goedert, Chair Caitlin E. Jewitt Karin Kitchens December 12, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: (voter registration, Shelby County v Holder, representation, migration) Legal Dodges and Subterfuges: Measuring Impact of New Obstacles on Minority Voter Registration Jennifer Ann Hitchcock ACADEMIC ABSTRACT Nearly 350 years of politically sanctioned domination over Blacks ended with the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in 1965. The federal regulation of voter and election law sought to end retrogressions in representation by intentional or effectual laws. In the VRA’s wake, race based politics and policy rooted in White supremacy were curtailed with the gradual representation of communities of color in all levels of government. Shelby County v Holder (2013) obstructed progress by effectively terminating preclearance of legal changes by the federal government. Since Shelby, retrogression of voter registration is once again on the rise. Remedies for retrogression require litigation and matriculation through the courts. This process is time consuming and allows states to conduct election law with minimal interruption until decisions are rendered. Research predating the passage of the Voting Rights Act by Matthews and Prothro indicated that there was a significant correlation between growing minority populations and the severity of election and voter laws. This paper seeks to determine if growing minority populations, in part due to disproportionately large in-migration, correlates with declining voter registration rates. -

Senate/House Education Authorizing Committees and Education Appropriations Subcommittees

Senate/House Education Authorizing Committees and Education Appropriations Subcommittees Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee (HELP) Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray (D-WA) Chair Richard M. Burr (R-NC) Ranking Member Bernie Sanders (I-VT) Rand Paul (R-KY) Bob Casey, Jr. (D-PA) Susan M. Collins (R-ME) Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Chris Murphy (D-CT) Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) Tim Kaine (D-VA) Mike Braun (R-IN) Maggie Hassan (D-NH) Roger Marshall (R-KS) Tina Smith (D-MN) Tim Scott (R-SC) Jacky Rosen (D-NV) Mitt Romney (R-UT) Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) John Hickenlooper (D-CO) Jerry Moran (R-KS) Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray (D-WA) Chair Roy Blunt (R-MO) Ranking Member Richard J. "Dick" Durbin (D-IL) Richard C. Shelby (R-AL) Jack Reed (D-RI) Lindsey Graham (R-SC) Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) Jerry Moran (R-KS) Jeff Merkley (D-OR) Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) Brian E. Schatz (D-HI) John Kennedy (R-LA) Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) Cindy Hyde-Smith (MS) Chris Murphy (D-CT) Mike Braun (R-IN) Joe Manchin (D-WV) Marco Rubio (R-FL) House Committee on Education and Labor Majority Members Minority Members Robert "Bobby" Scott (D-VA) Chair Virginia Foxx (R-NC) Ranking Member Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ) Joe Wilson (R-SC) Joe Courtney (D-CT) Glenn W. "G.T." Thompson (R-PA) Tim Walberg (R-MI) Gregorio Kilili Sablan (D-Northern Mariana Islands) Glenn Grothman (R-WI) Frederica S. -

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

Racism Is a Virus Toolkit

Table of Contents About This Toolkit.............................................................................................................03 Know History, Know Racism: A Brief History of Anti-AANHPI Racism............04 Exclusion and Colonization of AANHPI People.............................................04 AANHPI Panethnicity.............................................................................................07 Racism Resurfaced: COVID-19 and the Rise of Xenophobia...............................08 Continued Trends....................................................................................................08 Testimonies...............................................................................................................09 What Should I Do If I’m a Victim of a Hate Crime?.........................................10 What Should I Do If I Witness a Hate Crime?..................................................12 Navigating Unsteady Waters: Confronting Racism with your Parents..............13 On Institutional and Internalized Anti-Blackness..........................................14 On Institutionalized Violence...............................................................................15 On Protests................................................................................................................15 General Advice for Explaning Anti-Blackness to Family.............................15 Further Resources...................................................................................................15 -

The History of Redistricting in Georgia

GEORGIA LAW REVIEW(DO NOT DELETE) 11/6/2018 8:33 PM THE HISTORY OF REDISTRICTING IN GEORGIA Charles S. Bullock III* In his memoirs, Chief Justice Earl Warren singled out the redistricting cases as the most significant decisions of his tenure on the Court.1 A review of the changes redistricting introduced in Georgia supports Warren’s assessment. Not only have the obligations to equalize populations across districts and to do so in a racially fair manner transformed the makeup of the state’s collegial bodies, Georgia has provided the setting for multiple cases that have defined the requirements to be met when designing districts. Other than the very first adjustments that occurred in the 1960s, changes in Georgia plans had to secure approval from the federal government pursuant to the Voting Rights Act. Also, the first four decades of the Redistricting Revolution occurred with a Democratic legislature and governor in place. Not surprisingly, the partisans in control of redistricting sought to protect their own and as that became difficult they employed more extreme measures. When in the minority, Republicans had no chance to enact plans on their own. Beginning in the 1980s and peaking a decade later, Republicans joined forces with black Democrats to devise alternatives to the proposals of white Democrats. The biracial, bipartisan coalition never had sufficient numbers to enact its ideas. After striking out in the legislature, African-Americans appealed to the U.S. Attorney General alleging that the plans enacted were less favorable to black interests than alternatives * Charles S. Bullock, III is a University Professor of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia where he holds the Richard B. -

James.Qxp March Apri

COBB COUNTY A BUSTLING MARCH/APRIL 2017 PAGE 26 AN INSIDE VIEW INTO GEORGIA’S NEWS, POLITICS & CULTURE THE 2017 MOST INFLUENTIAL GEORGIA LOTTERY CORP. CEO ISSUE DEBBIE ALFORD COLUMNS BY KADE CULLEFER KAREN BREMER MAC McGREW CINDY MORLEY GARY REESE DANA RICKMAN LARRY WALKER The hallmark of the GWCCA Campus is CONNEE CTIVITY DEPARTMENTS Publisher’s Message 4 Floating Boats 6 FEATURES James’ 2017 Most Influential 8 JAMES 18 Saluting the James 2016 “Influentials” P.O. BOX 724787 ATLANTA, GEORGIA 31139 24 678 • 460 • 5410 Georgian of the Year, Debbie Alford Building A Proposed Contiguous Exhibition Facilityc Development on the Rise in Cobb County 26 PUBLISHED BY by Cindy Morley INTERNET NEWS AGENCY LLC 2017 Legislators of the Year 29 Building B CHAIRMAN MATTHEW TOWERY COLUMNS CEO & PUBLISHER PHIL KENT Future Conventtion Hotel [email protected] Language Matters: Building C How We Talk About Georgia Schools 21 CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER LOUIE HUNTER by Dr. Dana Rickman ASSOCIATE EDITOR GARY REESE ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES Georgia’s Legal Environment on a PATTI PEACH [email protected] Consistent Downward Trend 23 by Kade Cullefer The connections between Georggia World Congress Center venues, the hotel MARKETING DIRECTOR MELANIE DOBBINS district, and the world’world s busiest aairporirport are key differentiaferentiatorsators in Atlanta’Atlanta’s ability to [email protected] Georgia Restaurants Deliver compete for in-demand conventions and tradeshows. CIRCULATION PATRICK HICKEY [email protected] Significant Economic Impact 31 by Karen Bremer CONTRIBUTING WRITERS A fixed gateway between the exhibit halls in Buildings B & C would solidify KADE CULLEFER 33 Atlanta’s place as the world’s premier convention destination. -

Georgia Bar Journal Welcomes the Submission of EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PRESIDENT 800-334-6865 Ext

June 2017 Volume 22, Number 7 From the President— GEORGIA BAR Help Wanted: Lawyers Needed in the Legislature A Conversation with JOURNAL Edward D. Tolley 2017 Legislative Review 2017 Fiction Writing Competition Winner: Keep Things Merry THE LEGAL How Not to Get Thrown in Jail WWW. GABAR. ORG visit for the most up-to-date information on committees, members, courts and rules. ADMINISTERED BY: Lawyers Professional Liability Have your PROFESSIONAL LIABILITY RATES SKYROCKETED? NEW! Lawyers’ Professional Liability Insurance Program for State Bar of Georgia Members! If you’ve noticed the cost of your Lawyers’ Professional Liability is on the rise, we may be able to help! PROGRAM DETAILS: Special rates Multi-carrier Solution Risk Management for Georgia to accommodate all Expertise & Law Firms size and firm types Resources Get a quote for Lawyers’ Professional Liability Insurance at www.memberbenefits.com/gabar or call 281-374-4501. Products sold and serviced by the State Bar of Georgia’s recommended broker, Member Benefits. The State Bar of Georgia is not a licensed insurance entity and does not sell insurance. JUNE 2017 HEADQUARTERS COASTAL GEORGIA OFFICE SOUTH GEORGIA OFFICE INSTITUTE OF CONTINUING LEGAL EDUCATION 104 Marietta St. NW, Suite 100 18 E. Bay St. 244 E. Second St. (31794) 248 Prince Ave. Atlanta, GA 30303 Savannah, GA 31401-1225 P.O. Box 1390 P.O. Box 1855 800-334-6865 | 404-527-8700 877-239-9910 | 912-239-9910 Tifton, GA 31793-1390 Athens, GA 30603-1855 Fax 404-527-8717 Fax 912-239-9970 800-330-0446 | 229-387-0446 800-422-0893 | 706-369-5664 www.gabar.org Fax 229-382-7435 Fax 706-354-4190 EDITORIAL OFFICERS OF THE QUICK DIAL MANUSCRIPT SUBMISSION BOARD STATE BAR OF GEORGIA ATTORNEY DISCIPLINE The Georgia Bar Journal welcomes the submission of EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PRESIDENT 800-334-6865 ext. -

Sam Oh, [email protected] CA-39 NEWS

View this email in your browser FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Sam Oh, [email protected] CA-39 NEWS: Young Kim Raises Nearly $490K In Last FEC Quarter of 2019 Kim Q4 Fundraising Numbers Near the Top of House Challengers Across the Country Fullerton, CA – Today, the Young Kim for Congress campaign announced they raised nearly $490,000 in the Federal Election Commission’s 4th quarter to close out an impressive 2019. The significant haul puts her near the top of all House challengers across the country. The Young Kim for Congress campaign also reported ending the year with nearly $900,000 cash-on-hand and raising over $1.3 million in just 8 months in 2019. As Kim builds the war chest she needs to defeat Gil Cisneros, she also rolled out numerous key national and local endorsements in the final three months of 2019. Kim’s strong campaign infrastructure has attracted notice from the NRCC and the DCCC, who both have California’s 39th District as a key battleground seat in the fight for the House majority. “There is a reason Young is posting strong fundraising numbers and attracting endorsements from all across the country - she is a hardworking and dynamic candidate who is incredibly qualified and has everything it will take to win back this seat,” stated Sam Oh, general consultant to the Kim campaign. “Gil Cisneros has spent his first year in D.C. in lock step with Nancy Pelosi and his constituents are fed up.” Young has close to 200 federal and local leaders supporting her candidacy and also has been endorsed by the California, Orange County, Los Angeles County, and San Bernardino County Republican Parties. -

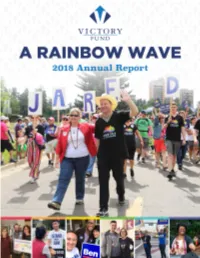

2018 Annual Report | 1 “From the U.S

A Rainbow Wave: 2018 Annual Report | 1 “From the U.S. Congress to statewide offices to state legislatures and city councils, on Election Night we made historic inroads and grew our political power in ways unimaginable even a few years ago.” MAYOR ANNISE PARKER, PRESIDENT & CEO LGBTQ VICTORY FUND BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chris Abele, Chair Michael Grover Richard Holt, Vice Chair Kim Hoover Mattheus Stephens, Secretary Chrys Lemon Campbell Spencer, Treasurer Stephen Macias Stuart Appelbaum Christopher Massicotte (ex-officio) Susan Atkins Daniel Penchina Sue Burnside (ex-officio) Vince Pryor Sharon Callahan-Miller Wade Rakes Pia Carusone ONE VICTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS LGBTQ VICTORY FUND CAMPAIGN BOARD LEADERSHIP Richard Holt, Chair Chris Abele, Vice Chair Sue Burnside, Co-Chair John Tedstrom, Vice Chair Chris Massicotte, Co-Chair Claire Lucas, Treasurer Jim Schmidt, Endorsement Chair Campbell Spencer, Secretary John Arrowood LGBTQ VICTORY FUND STAFF Mayor Annise Parker, President & CEO Sarah LeDonne, Digital Marketing Manager Andre Adeyemi, Executive Assistant / Board Liaison Tim Meinke, Senior Director of Major Gifts Geoffrey Bell, Political Manager Sean Meloy, Senior Political Director Robert Byrne, Digital Communications Manager Courtney Mott, Victory Campaign Board Director Katie Creehan, Director of Operations Aaron Samulcek, Chief Operations Officer Dan Gugliuzza, Data Manager Bryant Sanders, Corporate and Foundation Gifts Manager Emily Hammell, Events Manager Seth Schermer, Vice President of Development Elliot Imse, Senior Director of Communications Cesar Toledo, Political Associate 1 | A Rainbow Wave: 2018 Annual Report Friend, As the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising approaches this June, I am reminded that every so often—perhaps just two or three times a decade—our movement takes an extraordinary leap forward in its march toward equality. -

December 12, 2018 Michael R. Pompeo US

December 12, 2018 Michael R. Pompeo U.S. Department of State 2201 C Street NW Washington, DC 20520 Dear Secretary Pompeo: We write to express our deep concern about the potential deportation of thousands of Vietnamese refugees under pressure from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to change the terms of the current repatriation agreement between Vietnam and the United States.1 This longstanding agreement, which was signed by the U.S. and Vietnamese governments in 2008 under President George W. Bush, does not provide for the deportation of any Vietnamese citizens who arrived in the United States before July 12, 1995. [Article 2, Para. 2] Even for those who came to the U.S. after July 12, 1995, the agreement promises to “take into account the humanitarian aspect, family unity and circumstances” of each person being considered for repatriation and to carry out repatriation “in an orderly and safe way, and with respect for the individual human dignity of the person repatriated.” [Article I, Para. 1,3] The terms of this agreement recognize the complex history between the two countries and the dire circumstances under which hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese fled to the U.S. to seek refuge from political persecution in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Many of those who fled were South Vietnamese who had fought alongside or otherwise supported the U.S. government during the war. Upon their arrival into the U.S., Vietnamese refugees, many of them young children or teenagers, were resettled in struggling neighborhoods without support or resources to cope with significant trauma from the war.