Serendipitous Discovery of First Two Antidepressants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies on Mammalian Histidine Decarboxylase by N

Brit. J. Pharmacol. (1956), 11, 119. STUDIES ON MAMMALIAN HISTIDINE DECARBOXYLASE BY N. G. WATON* From the Department ofPharmacology, University ofEdinburgh (RECEIVED SEPTEMBER 12, 1955) Histamine is present in most mammalian tissues, occurrence of an enzyme capable of decarboxylating but its mode of formation is still not clear. Accord- histidine in all mammals, as the experiments were ing to Blaschko (1945) there are two main theories: confined to a limited range of mammalian species. (1) Histamine is a vitamin, formed outside the The properties and the distribution in laboratory body by bacterial decarboxylation of dietary animals of mammalian histidine decarboxylase, histidine in the alimentary tract. (2) Histamine is a together with the distribution of histaminase and metabolite, formed from circulating histidine by histamine, have been reinvestigated in the hope of the histidine decarboxylase present in some tissues clarifying our knowledge of the role of histamine in of the body. the organism. That bacteria form histamine by decarboxylation METHODS of histidine is well known (Ackermann, 1910, 1911; Formation of Histamine from Histidine by Mammalian Berthelot and Bertrand, 1912; Mellanby and Twort, Tissues 1912; Kendall and Gebauer, 1930; Matsuda, 1933; Rabbit kidneys, which are a rich source of histidine Gale, 1940; Epps, 1945). Gale (1953) showed that decarboxylase, were placed in 0.9% w/v NaCl, freed the bacterial enzyme had several important differen- from all extraneous tissue, cut small and minced in a ces from the other amino acid decarboxylases which Latapie mincing machine. Where a tissue extract was had been studied. required, the minced kidney was ground for 10 min. -

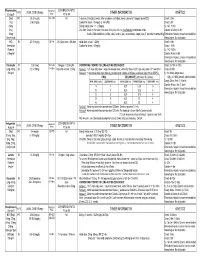

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

The Effects of Phenelzine and Other Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor

British Journal of Phammcology (1995) 114. 837-845 B 1995 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0007-1188/95 $9.00 The effects of phenelzine and other monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants on brain and liver 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors Regina Alemany, Gabriel Olmos & 'Jesu's A. Garcia-Sevilla Laboratory of Neuropharmacology, Department of Fundamental Biology and Health Sciences, University of the Balearic Islands, E-07071 Palma de Mallorca, Spain 1 The binding of [3H]-idazoxan in the presence of 106 M (-)-adrenaline was used to quantitate 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors in the rat brain and liver after chronic treatment with various irre- versible and reversible monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors. 2 Chronic treatment (7-14 days) with the irreversible MAO inhibitors, phenelzine (1-20 mg kg-', i.p.), isocarboxazid (10 mg kg-', i.p.), clorgyline (3 mg kg-', i.p.) and tranylcypromine (10mg kg-', i.p.) markedly decreased (21-71%) the density of 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors in the rat brain and liver. In contrast, chronic treatment (7 days) with the reversible MAO-A inhibitors, moclobemide (1 and 10 mg kg-', i.p.) or chlordimeform (10 mg kg-', i.p.) or with the reversible MAO-B inhibitor Ro 16-6491 (1 and 10 mg kg-', i.p.) did not alter the density of 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors in the rat brain and liver; except for the higher dose of Ro 16-6491 which only decreased the density of these putative receptors in the liver (38%). 3 In vitro, phenelzine, clorgyline, 3-phenylpropargylamine, tranylcypromine and chlordimeform dis- placed the binding of [3H]-idazoxan to brain and liver I2 imidazoline-preferring receptors from two distinct binding sites. -

NORPRAMIN® (Desipramine Hydrochloride Tablets USP)

NORPRAMIN® (desipramine hydrochloride tablets USP) Suicidality and Antidepressant Drugs Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of NORPRAMIN or any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older. Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. NORPRAMIN is not approved for use in pediatric patients. (See WARNINGS: Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk, PRECAUTIONS: Information for Patients, and PRECAUTIONS: Pediatric Use.) DESCRIPTION NORPRAMIN® (desipramine hydrochloride USP) is an antidepressant drug of the tricyclic type, and is chemically: 5H-Dibenz[bƒ]azepine-5-propanamine,10,11-dihydro-N-methyl-, monohydrochloride. 1 Reference ID: 3536021 Inactive Ingredients The following inactive ingredients are contained in all dosage strengths: acacia, calcium carbonate, corn starch, D&C Red No. 30 and D&C Yellow No. 10 (except 10 mg and 150 mg), FD&C Blue No. 1 (except 25 mg, 75 mg, and 100 mg), hydrogenated soy oil, iron oxide, light mineral oil, magnesium stearate, mannitol, polyethylene glycol 8000, pregelatinized corn starch, sodium benzoate (except 150 mg), sucrose, talc, titanium dioxide, and other ingredients. -

Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics

TESI DOCTORAL HUMAN PHARMACOLOGY OF AYAHUASCA JORDI RIBA Barcelona, 2003 Director de la Tesi: DR. MANEL JOSEP BARBANOJ RODRÍGUEZ A la Núria, el Marc i l’Emma. No pasaremos en silencio una de las cosas que á nuestro modo de ver llamará la atención... toman un bejuco llamado Ayahuasca (bejuco de muerto ó almas) del cual hacen un lijero cocimiento...esta bebida es narcótica, como debe suponerse, i á pocos momentos empieza a producir los mas raros fenómenos...Yo, por mí, sé decir que cuando he tomado el Ayahuasca he sentido rodeos de cabeza, luego un viaje aéreo en el que recuerdo percibia las prespectivas mas deliciosas, grandes ciudades, elevadas torres, hermosos parques i otros objetos bellísimos; luego me figuraba abandonado en un bosque i acometido de algunas fieras, de las que me defendia; en seguida tenia sensación fuerte de sueño del cual recordaba con dolor i pesadez de cabeza, i algunas veces mal estar general. Manuel Villavicencio Geografía de la República del Ecuador (1858) Das, was den Indianer den “Aya-huasca-Trank” lieben macht, sind, abgesehen von den Traumgesichten, die auf sein persönliches Glück Bezug habenden Bilder, die sein inneres Auge während des narkotischen Zustandes schaut. Louis Lewin Phantastica (1927) Agraïments La present tesi doctoral constitueix la fase final d’una idea nascuda ara fa gairebé nou anys. El fet que aquest treball sobre la farmacologia humana de l’ayahuasca hagi estat una realitat es deu fonamentalment al suport constant del seu director, el Manel Barbanoj. Voldria expressar-li la meva gratitud pel seu recolzament entusiàstic d’aquest projecte, molt allunyat, per la natura del fàrmac objecte d’estudi, dels que fins al moment s’havien dut a terme a l’Àrea d’Investigació Farmacològica de l’Hospital de Sant Pau. -

(DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact

pharmaceuticals Review Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics of Ayahuasca Alkaloids N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact Andreia Machado Brito-da-Costa 1 , Diana Dias-da-Silva 1,2,* , Nelson G. M. Gomes 1,3 , Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira 1,2,4,* and Áurea Madureira-Carvalho 1,3 1 Department of Sciences, IINFACTS-Institute of Research and Advanced Training in Health Sciences and Technologies, University Institute of Health Sciences (IUCS), CESPU, CRL, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal; [email protected] (A.M.B.-d.-C.); ngomes@ff.up.pt (N.G.M.G.); [email protected] (Á.M.-C.) 2 UCIBIO-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Toxicology, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 3 LAQV-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 4 Department of Public Health and Forensic Sciences, and Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, 4200-319 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.D.-d.-S.); [email protected] (R.J.D.-O.); Tel.: +351-224-157-216 (R.J.D.-O.) Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic botanical beverage originally used by indigenous Amazonian tribes in religious ceremonies and therapeutic practices. While ethnobotanical surveys still indicate its spiritual and medicinal uses, consumption of ayahuasca has been progressively related with a recreational purpose, particularly in Western societies. The ayahuasca aqueous concoction is typically prepared from the leaves of the N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-containing Psychotria viridis, and the stem and bark of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of harmala alkaloids. -

Neuroprotection by Chlorpromazine and Promethazine in Severe Transient and Permanent Ischemic Stroke

Mol Neurobiol (2017) 54:8140–8150 DOI 10.1007/s12035-016-0280-x Neuroprotection by Chlorpromazine and Promethazine in Severe Transient and Permanent Ischemic Stroke Xiaokun Geng1,2 & Fengwu Li1 & James Yip2 & Changya Peng2 & Omar Elmadhoun2 & Jiamei Shen1 & Xunming Ji1,3 & Yuchuan Ding1,2 Received: 29 June 2016 /Accepted: 31 October 2016 /Published online: 28 November 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Previous studies have demonstrated depressive or enhance C + P-induced neuroprotection. C + P therapy im- hibernation-like roles of phenothiazine neuroleptics [com- proved brain metabolism as determined by increased ATP bined chlorpromazine and promethazine (C + P)] in brain levels and NADH activity, as well as decreased ROS produc- activity. This ischemic stroke study aimed to establish neuro- tion. These therapeutic effects were associated with alterations protection by reducing oxidative stress and improving brain in PKC-δ and Akt protein expression. C + P treatments con- metabolism with post-ischemic C + P administration. ferred neuroprotection in severe stroke models by suppressing Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to transient (2 or 4 h) the damaging cascade of metabolic events, most likely inde- middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) followed by 6 or pendent of drug-induced hypothermia. These findings further 24 h reperfusion, or permanent (28 h) MCAO without reper- prove the clinical potential for C + P treatment and may direct fusion. At 2 h after ischemia onset, rats received either an us closer towards the development of an efficacious neuropro- intraperitoneal (IP) injection of saline or two doses of C + P. tective therapy. Body temperatures, brain infarct volumes, and neurological deficits were examined. -

Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment for Schizophrenia in Adult Patients? Kyle J

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine DigitalCommons@PCOM PCOM Physician Assistant Studies Student Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers Scholarship 2017 Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment For Schizophrenia In Adult Patients? Kyle J. Knowles Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/pa_systematic_reviews Part of the Psychiatry Commons Recommended Citation Knowles, Kyle J., "Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment For Schizophrenia In Adult Patients?" (2017). PCOM Physician Assistant Studies Student Scholarship. 381. https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/pa_systematic_reviews/381 This Selective Evidence-Based Medicine Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers at DigitalCommons@PCOM. It has been accepted for inclusion in PCOM Physician Assistant Studies Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@PCOM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment For Schizophrenia In Adult Patients? Kyle J. Knowles, PA-S A SELECTIVE EVIDENCE BASED MEDICINE REVIEW In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For The Degree of Master of Science In Health Sciences- Physician Assistant Department of Physician Assistant Studies Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania December 16, 2016 ABSTRACT OBJECTIVE: The objective of this selective EBM review is to determine whether or not “Is Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil) a safe and effective treatment for schizophrenia in adult patients?” STUDY DESIGN: Review of three randomized controlled studies. All three trials were conducted between 2014 and 2015. DATA SOURCES: One randomized, controlled trial and two randomized, controlled, double- blind trials found via Cochrane Library and PubMed. -

A Drug Repositioning Approach Identifies Tricyclic Antidepressants As Inhibitors of Small Cell Lung Cancer and Other Neuroendocrine Tumors

Published OnlineFirst September 26, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0183 RESEARCH ARTICLE A Drug Repositioning Approach Identifi es Tricyclic Antidepressants as Inhibitors of Small Cell Lung Cancer and Other Neuroendocrine Tumors Nadine S. Jahchan 1 , 2 , Joel T. Dudley 1 , Pawel K. Mazur 1 , 2 , Natasha Flores 1 , 2 , Dian Yang 1 , 2 , Alec Palmerton 1 , 2 , Anne-Flore Zmoos 1 , 2 , Dedeepya Vaka 1 , 2 , Kim Q.T. Tran 1 , 2 , Margaret Zhou 1 , 2 , Karolina Krasinska 3 , Jonathan W. Riess 4 , Joel W. Neal 5 , Purvesh Khatri 1 , 2 , Kwon S. Park 1 , 2 , Atul J. Butte 1 , 2 , and Julien Sage 1 , 2 Downloaded from cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org on September 29, 2021. © 2013 American Association for Cancer Research. Published OnlineFirst September 26, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0183 ABSTRACT Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine subtype of lung cancer with high mortality. We used a systematic drug repositioning bioinformat- ics approach querying a large compendium of gene expression profi les to identify candidate U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs to treat SCLC. We found that tricyclic antidepressants and related molecules potently induce apoptosis in both chemonaïve and chemoresistant SCLC cells in culture, in mouse and human SCLC tumors transplanted into immunocompromised mice, and in endog- enous tumors from a mouse model for human SCLC. The candidate drugs activate stress pathways and induce cell death in SCLC cells, at least in part by disrupting autocrine survival signals involving neurotransmitters and their G protein–coupled receptors. The candidate drugs inhibit the growth of other neuroendocrine tumors, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. -

Nialamide; SOCIETIES and LECTURES CORRECTION

414 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 15 MAY 1971 care, and administration of health services. A. Clements, P. A. Connell, Patricia A. Crawford, G. A. Cupper, M. R. Dean, L. L. Dom- "It is, in short, medicine applied to a group SOCIETIES AND LECTURES bey, D. P. De Bono, J. P. Delamere, Gil- than to an individual patient." The lean P. Duncan, D. B. Dunger, C. E. G. Farqu- rather Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.5758.414 on 15 May 1971. Downloaded from statement adds that it is hoped that the pro- For attending lectures marked * a fee is charged or harson, Pamela C. Fenney, Daphne C. Fielding, a ticket is required. Applications should be made I. R. Fletcher, M. S. Fletcher, Po-Kai Fok, G. J. visional Faculty will be in a position to re- Frost, R. M. Galbraith, Elizabeth A. S. Galvin, first to the institution concerned. D. J. Giraldi, Jenifer I. Glover, B. A. Greenway, ceive applications from those wishing to be- Mary Griffin, J. F. Hamlyn, M. H. Hampton, come founder members later in the year. Monday, 17 May G. P. Harris, P. B. Harvey, A. C. Hillyard, Gillian M. M. Hodge, N. Holmes, Sheilagh M. Further announcements will be made. ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY.-At Medical Buildings, Hope, C. C. Hugh, Joanna E. Ide, Alison Ironside, Foresterhill, 5.30 p.m., dentj centennial lecture Keatley E. James, W. J. Jarrett, Celia A. Jenkins, by Sir Robert Bradlaw: Pigmentation. J. R. Jenner, P. D. Jones, C. L. Kennedy, N. D. Monoamine-oxidase Inhibitors INSTITUTE OF DERMATOLOGY.-4.30 p.m., Mr. -

Antipsychotic Combinations

Graylands Hospital DRUG BULLETIN Pharmacy Department Brockway Road Mount Claremont WA 6010 Telephone (08) 9347 6400 Email [email protected] Fax (08) 9384 4586 Antipsychotic Combinations Graylands Hospital Drug Bulletin 2008 Vol. 15 No. 3 February ISSN 1323-1251 Antipsychotic combinations Reasons for antipsychotic combinations Despite the development of efficacious medications for the treatment of schizophrenia, many people do There are a number of theoretical benefits and not respond adequately. To address this problem, reasons cited for antipsychotic combination the use of two or more antipsychotics simultaneously prescribing, these include: is a commonly employed treatment strategy. Although the use of combination antipsychotics is Complementary mechanisms of action4 (e.g. common in clinical practice, the risks and benefits adding an antipsychotic with strong dopamine have not been systematically evaluated to date. As a D2 blockade to a weak D2 blocker) result, current Australian treatment algorithms Partial replacement of antipsychotic action for including the Royal Australian and New Zealand drugs with intolerable adverse effects at higher College of Psychiatry Schizophrenia Guidelines and 5 doses (e.g. adding quetiapine to clozapine to the Western Australian Therapeutic Advisory Group minimise metabolic adverse effects) Antipsychotic Guidelines advise against the use of combined antipsychotics, except for short periods of Alternative where clozapine cannot be used6 changeover1,2. Most data on antipsychotic -

New Drugs Are Not Enough‑Drug Repositioning in Oncology: an Update

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 56: 651-684, 2020 New drugs are not enough‑drug repositioning in oncology: An update ROMINA GABRIELA ARMANDO, DIEGO LUIS MENGUAL GÓMEZ and DANIEL EDUARDO GOMEZ Laboratory of Molecular Oncology, Science and Technology Department, National University of Quilmes, Bernal B1876, Argentina Received August 15, 2019; Accepted December 16, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/ijo.2020.4966 Abstract. Drug repositioning refers to the concept of discov- 17. Lithium ering novel clinical benefits of drugs that are already known 18. Metformin for use treating other diseases. The advantages of this are that 19. Niclosamide several important drug characteristics are already established 20. Nitroxoline (including efficacy, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and 21. Nonsteroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs toxicity), making the process of research for a putative drug 22. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors quicker and less costly. Drug repositioning in oncology has 23. Pimozide received extensive focus. The present review summarizes the 24. Propranolol most prominent examples of drug repositioning for the treat- 25. Riluzole ment of cancer, taking into consideration their primary use, 26. Statins proposed anticancer mechanisms and current development 27. Thalidomide status. 28. Valproic acid 29. Verapamil 30. Zidovudine Contents 31. Concluding remarks 1. Introduction 2. Artesunate 1. Introduction 3. Auranofin 4. Benzimidazole derivatives In previous decades, a considerable amount of work has been 5. Chloroquine conducted in search of novel oncological therapies; however, 6. Chlorpromazine cancer remains one of the leading causes of death globally. 7. Clomipramine The creation of novel drugs requires large volumes of capital, 8. Desmopressin alongside extensive experimentation and testing, comprising 9. Digoxin the pioneer identification of identifiable targets and corrobora- 10.