Gupta Efflorescence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAN REPUBLICAN CAVALRY TACTICS in the 3Rd-2Nd

ACTA MARISIENSIS. SERIA HISTORIA Vol. 2 (2020) ISSN (Print) 2668-9545 ISSN (Online) 2668-9715 DOI: 10.2478/amsh-2020-0008 “BELLATOR EQUUS”. ROMAN REPUBLICAN CAVALRY TACTICS IN THE 3rd-2nd CENTURIES BC Fábián István Abstact One of the most interesting periods in the history of the Roman cavalry were the Punic wars. Many historians believe that during these conflicts the ill fame of the Roman cavalry was founded but, as it can be observed it was not the determination that lacked. The main issue is the presence of the political factor who decided in the main battles of this conflict. The present paper has as aim to outline a few aspects of how the Roman mid-republican cavalry met these odds and how they tried to incline the balance in their favor. Keywords: Republic; cavalry; Hannibal; battle; tactics The main role of a well performing cavalry is to disrupt an infantry formation and harm the enemy’s cavalry units. From this perspective the Roman cavalry, especially the middle Republican one, performed well by employing tactics “if not uniquely Roman, were quite distinct from the normal tactics of many other ancient Mediterranean cavalry forces. The Roman predilection to shock actions against infantry may have been shared by some contemporary cavalry forces, but their preference for stationary hand-to-hand or dismounted combat against enemy cavalry was almost unique to them”.1 The main problem is that there are no major sources concerning this period except for Polibyus and Titus Livius. The first may come as more reliable for two reasons: he used first-hand information from the witnesses of the conflicts between 220-167 and ”furthermore Polybius’ account is particularly valuable because he had serves as hypparch in Achaea and clearly had interest and aptitude in analyzing military affairs”2. -

Failure in 1813: the Decline of French Light Infantry and Its Effect on Napoleon’S German Campaign

United States Military Academy USMA Digital Commons Cadet Senior Theses in History Department of History Spring 4-14-2018 Failure in 1813: The eclineD of French Light Infantry and its effect on Napoleon's German Campaign Gustave Doll United States Military Academy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/history_cadet_etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Doll, Gustave, "Failure in 1813: The eD cline of French Light Infantry and its effect on Napoleon's German Campaign" (2018). Cadet Senior Theses in History. 1. https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/history_cadet_etd/1 This Bachelor's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at USMA Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cadet Senior Theses in History by an authorized administrator of USMA Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. United States Military Academy USMA Digital Commons Cadet Senior Theses in History Department of History Spring 4-14-2018 Failure in 1813: The eclineD of French Light Infantry and its effect on Napoleon's German Campaign Gustave Doll Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/history_cadet_etd UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY FAILURE IN 1813: THE DECLINE OF FRENCH LIGHT INFANTRY AND ITS EFFECT ON NAPOLEON’S GERMAN CAMPAIGN HI499: SENIOR THESIS SECTION S26 CPT VILLANUEVA BY CADET GUSTAVE A DOLL, ’18 CO F3 WEST POINT, NEW YORK 19 APRIL 2018 ___ MY DOCUMENTATION IDENTIFIES ALL SOURCES USED AND ASSISTANCE RECEIVED IN COMPLETING THIS ASSIGNMENT. ___ NO SOURCES WERE USED OR ASSISTANCE RECEIVED IN COMPLETING THIS ASSIGNMENT. -

Lecture 5 the Birth of the Hoplite I

Warfare and Society in Ancient Greece Lecture 5 The birth of the hoplite I The birth of the hoplites Aristotle, Politics IV.1397b 5 It is proper that the government should be drawn only from those who possess heavy armor. Aristotle, Politics IV.1397b 16-28 The first political regime after the monarchies was composed of warriors and originally drawn from cavalry, for strength and superiority in warfare belonged to the cavalry. Without order heavy infantry is useless. In early times there was neither sound empirical practice in these matters nor rules for it, with the result that mastery on the battlefield rested with the cavalry. When the cities increased in population and number with arms became larger, then they took a share in the governing process. For this reason the constitutions we now call polities the ancients called democracies, for the middling class were few in number due to the smallness of the population, and consequently before this there was a small middling class, and given the form of contemporary military organization the people more easily tolerated being commanded. Cultural heritage of hoplitism Diodorus 15.44.3 Those who had previously called hoplites, from the shield they carried had their name changed to peltasts from the name of their new shield, the pelta. Hoplite ethics and the shield Plutarch, Moralia 220A, Sayings of the Spartans When someone asked Demaratus why the Spartans disgrace those who throw away their shields but no those who abandon their breastplates or helmets, he said that they put the latter on for their own sakes but the shield for the sake of the whole line. -

Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity Kevin Patrick Emery Wofford College

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Student Scholarship 5-2016 Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity Kevin Patrick Emery Wofford College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/studentpubs Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Emery, Kevin Patrick, "Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity" (2016). Student Scholarship. Paper 11. http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/studentpubs/11 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wofford College Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity An Honors Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy For An Honors Degree in History By Kevin Patrick Emery Spartanburg, South Carolina May 2016 1 Introduction The story of the mercenary armies of Carthage is one of incompetence and disaster, followed by clever innovation. It is a story not just of battles and betrayal, but also of the interactions between dissimilar peoples in a multiethnic army trying to coordinate, fight, and win, while commanded by a Punic officer corps which may or may not have been competent. Carthaginian mercenaries are one piece of a larger narrative about the struggle between Carthage and Rome for dominance in the Western Mediterranean, and their history illustrates the evolution of the mercenary system employed by the Carthaginian Empire to extend her power and ensure her survival. -

Rules Manual ~ a Richard Berg - Mark Herman Design ~ Table • of • Contents (1.0) Introduction

Warfare in the Greco-Persian Age 5th-4th Century BC The Battles of Ephesus, Marathon, Plataea, Mycale, Tanagra, Delium, Cunaxa, Nemea, Coronea, Leuctra, and Mantinea Rules Manual ~ a Richard Berg - Mark Herman design ~ Table • of • Contents (1.0) Introduction ......................................................... 3 (7.0) Missile Combat .................................................... 15 (2.0) Components & Terms ......................................... 3 (8.0) Shock Combat ...................................................... 18 (3.0) The Sequence of Play .......................................... 5 (9.0) Special Units & Rules .......................................... 24 (4.0) Leaders ................................................................. 6 (10.0) Effects of Combat .............................................. 28 (5.0) Activation & Orders ............................................ 7 (11.0) Army Withdrawal & Victory ............................ 30 (6.0) Movement ............................................................. 9 GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com 2 Hoplite ~ Rules of Play (2.0) Components & Terms Each Game of Hoplite contains: 3 22" x 34” mapsheets, backprinted 4 Sheets of game pieces (units & markers) (1.0) Introduction 1 Rules Booklet Hoplite (HOP), the 15th volume in the Great Battles of His- 1 Scenario Booklet tory series of games, allows players to recreate classic battles 6 17" x 11" Player Aid cards (two of each) from the pre-Alexandrian Greco-Persian Age, the -

Advancing and Understanding of Military, Robotic Exoskeletons

Advancing an Understanding of Military, Robotic Exoskeletons STEVEN YEADON This article surveys an understanding of robotic exoskeletons in relation to the infantry. “Robotic exoskeletons are electronic devices that attach to a human user’s body and contain actuators that deliver mechanical power to augment movement. One class of these devices facilitates upper-limb movements such as reaching, grasping, or lifting with the arm or hand. The other primary category of robotic exoskeletons augments lower limb functions such as sitting down, standing up, walking, balancing, and standing. Full body exoskeletons can fulfill a combination of these purposes.”1 There are three broad types of robotic exoskeletons: assistive devices for those with disabilities, therapeutic robotic exoskeletons for rehabilitation, and human performance augmentation exoskeletons intended to increase strength, endurance, and other physical capabilities of able-bodied people.² This last type of exoskeleton is what my analysis will focus on. In my opinion, robotic exoskeletons represent more than an enhancement to current infantry. Military, robotic exoskeletons can create a distinct kind of heavy infantry unit that can improve current U.S. Army combined arms teams. This objective may be feasible sooner than one may think if robotic exoskeleton-equipped formations have an expanded logistical footprint, which includes the need for a regular supply of charged batteries as well as other logistical concerns. However, this is an untested future military concept, and my analysis is meant only to stimulate discussion on how to employ exoskeletons in military operations. This article will cover military applications of exoskeletons, current exoskeleton technologies, previous military concepts, possible solutions to potential issues, and other concerns regarding the employment of heavy infantry using robotic exoskeletons. -

Deluxe Alex-4

THE Table of Contents MACEDONIAN Rules Section Page ART OF WAR 1.0 Introduction ......................... 2 338–326 B.C. 2.0 Game Components .............. 2 3.0 The Sequence of Play .......... 6 4.0 Leaders ................................ 6 5.0 Leader Activation/Orders .... 9 6.0 Movement ........................... 12 7.0 Combat Movement .............. 16 8.0 Combat ................................ 17 GAME DESIGN: 9.0 Special Units ....................... 22 10.0 The Effects of Combat ........ 27 MARK HERMAN Sources ........................................ 29 RICHARD BERG ©2003 Rodger B. MacGowan RULES BOOKLET (1.0) INTRODUCTION (2.0) GAME COMPONENTS The Great Battles of Alexander the Great is the first volume/game Each Game of Deluxe Battles of Alexander contains: in GMT’s Great Battles of History series. It portrays the development of the Macedonian Art of War, as originally formulated by Philip II, 3 22” x 34” mapsheets, backprinted King of Macedon. It reached its peak during the reign of his son, 3 Sets of counters (720 counters total) Alexander III, who, after his conquest of the Persian Empire, became 1 Rules Booklet known as Alexander the Great. 1 Scenario Booklet 2 Player Aid Cards This special, “Deluxe” edition covers almost every battle fought by 1 ten-sided die Alexander and his army before and during his conquest of the civilized A bunch of glassine envelopes world (Western version). The battles illustrate the triumph of the Macedonian system of “combined arms”—led by a powerful heavy If you have any questions about these rules, we’ll be glad to (try to) cavalry and anchored by a relentless phalanx of spears—first over a answer them, if you send them to us in a self-addressed, stamped Greek hoplite system that had been in place for centuries, and then to (regardless where you’re from) envelope, addressed to: its ultimate fruition against the massive, but often out-of-date, “light” armies of the Persian Empire. -

Roman Warfare and Fortification

Roman Warfare and Fortification Oxford Handbooks Online Roman Warfare and Fortification Gwyn Davies The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World Edited by John Peter Oleson Print Publication Date: Dec 2009 Subject: Classical Studies, Ancient Roman History, Material Culture Studies Online Publication Date: Sep 2012 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734856.013.0028 Abstract and Keywords This article concentrates on the role of technology in improving the operational capabilities of the Roman state. It reviews the organizational and weapon system developments that enabled Roman armies to engage their enemies with confidence in the field, alongside the evolution of fortification schemes that enabled economies of force, which were essential to imperial security. Roman weapons and equipment include the spear, sword, missiles, artillery, shields, helmets, and body armor. Although the Roman army was often on the attack and made use of complex siege technology, it was also highly skilled in the preparation of defensive fortifications. The Romans diligently applied themselves to the arts of war. Their successful mastery of battlefield techniques and their adoption, where appropriate, of equipment and technologies first introduced by their opponents allowed Roman armies to sustain the state over several hundreds of years of challenge and change. Keywords: Roman armies, Roman warfare, Roman fortification, spear, sword, missiles, artillery, shields, helmets, body armor Warfare and the Romans A message relayed to the Roman people by Romulus after his translation to the heavens, stands as an unambiguous endorsement of Roman military prowess. “Tell the Romans that it is the gods' will that my Rome shall be the capital of the world; therefore let them cultivate the arts of war and let them know and teach their children that no human force can resist Roman arms” (Livy 1.16.7). -

Clad in Steel: the Evolution of Armor and Weapons in Medieval Europe

Clad in Steel: The Evolution of Armor and Weapons in Medieval Europe Jason Gill Honors Thesis Professor Katherine Smith and Professor William Barry 1 The sun rose over Northern France on October 25, 1415 to reveal two armies, one fighting for England, one for France. As the English advanced in good order toward their enemies, the sun at their backs, the steel plate of their knights seemed to shine in the morning light, even as the shafts of their archers cast shadows on the ground. The unprepared French forces hurried to strap on their armor plates and lock their visors into place, hoping these would protect them from the lethal rain their enemies brought against them, and hurried across the sodden field to meet the glistening blades of their foes, even as arrows descended upon them like hail. The slaughter that followed, which has come to be known as the battle of Agincourt, remains one of the most iconic and infamous engagements of the Middle Ages, with archers and knights in shining armor slaughtering each other in the thousands. For many of these soldiers, armor and skill were their only defenses against the assaults of their enemies, so it was fortunate that by the time of Agincourt armor design had become truly impressive. But how did this armor evolve to this point? What pushed armorers to continually improve their designs? And what weapons were brought to bear against it? All are important questions, and all deserve to be treated in depth. The evolution of armor, of course, is a complicated topic. -

Osgorthap2-Combat

COMBAT COMBAT FACTOR CHARTS O to - .3 Terrain differential; factors are subtracted from the unit in the appropriate terrain: 0 for clear The charts and tables listed below give a step-by-step terrain; 1 for low hills and light woods; 2 for high hills guide to the combat resolution system of The Shat and heavy woods; 3 for mountains; tered Alliance. For this battle, nothing on the Tactical Factor Chart When a unit engages an opponent in melee combat applies except the 1 factor bonus for attacking, which the outcome of the battle is determined by the number is given to the Extra-Heavy Cavalry. If the battle had of casualties caused. This is determined by the total been fought on different terrain or if magic had been number of combat factors each unit has when fighting used, we would have added the appropriate amounts an opponent The number of combat factors is the to the Tactical Factor total. The Combat Factors now total of weapon, tactical and random factors the unit total five for the Extra-Heavy Cavalry and four for the has during its attack. During an attack, both units Infantry. Next is the Random Factor Chart compile their combat factors, casualties are calculated and a victory result is declared. Weapon Factor Chart. MELEE RANDOM HI LHI Ml LMI LI EHC HC MC LC FACTOR CHART CAVALRY WEAPONS +3 to - 3 is the range of the melee random factor. Lance 4 4 4 4 5 .3 4 5 5 Thro average dice are rolled (2,3,.3,4,4,5) and the Javelin .3 .3 4 4 5 2 2 4 .3 second roll is subtracted from the first to produce the Sword 2 2 .3 .3 5 1 1 2 .3 random factor. -

Companion Cavalry and the Macedonian Heavy Infantry

THE ARMY OP ALEXANDER THE GREAT %/ ROBERT LOCK IT'-'-i""*'?.} Submitted to satisfy the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in the School of History in the University of Leeds. Supervisor: Professor E. Badian Date of Submission: Thursday 14 March 1974 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH X 5 Boston Spa, Wetherby </l *xj 1 West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ. * $ www.bl.uk BEST COPY AVAILABLE. TEXT IN ORIGINAL IS CLOSE TO THE EDGE OF THE PAGE ABSTRACT The army with which Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire was "built around the Macedonian Companion cavalry and the Macedonian heavy infantry. The Macedonian nobility were traditionally fine horsemen, hut the infantry was poorly armed and badly organised until the reign of Alexander II in 369/8 B.C. This king formed a small royal standing army; it consisted of a cavalry force of Macedonian nobles, which he named the 'hetairoi' (or Companion]! cavalry, and an infantry body drawn from the commoners and trained to fight in phalangite formation: these he called the »pezetairoi» (or foot-companions). Philip II (359-336 B.C.) expanded the kingdom and greatly increased the manpower resources for war. Towards the end of his reign he started preparations for the invasion of the Persian empire and levied many more Macedonians than had hitherto been involved in the king's wars. In order to attach these men more closely to himself he extended the meaning of the terms »hetairol» and 'pezetairoi to refer to the whole bodies of Macedonian cavalry and heavy infantry which served under him on his campaigning. -

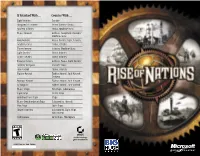

If Attacked with … Counter with …

If Attacked With … Counter With … Light Infantry Cavalry Gunpowder Infantry Heavy Cavalry, Tanks Modern Infantry Tanks, Machine Guns Heavy Infantry Archers, Gunpowder Infantry Machine Guns Foot Archers Heavy Cavalry, Light Infantry Machine Guns Tanks, Cavalry Flamethrower Infantry, Machine Guns Light Cavalry Heavy Infantry Heavy Cavalry Heavy Infantry Ranged Cavalry Archers, Tanks, Light Cavalry Artillery Weapons Cavalry, Tanks Anti-Aircraft Tanks, Infantry Fighter Aircraft Fighter Aircraft, Anti-Aircraft, Cruisers Bomber Aircraft Fighter Aircraft, Anti-Aircraft Helicopters Fighter Aircraft, Anti-Aircraft Heavy Ships Fire Ships, Submarines Light Ships Heavy Ships Bombardment Ships Ships Heavy Bombardment Ships Submarines, Aircraft Fire Ships Light Ships Aircraft Carriers Submarines, Light Ships, Anti-Aircraft Submarines Light Ships, Helicopters Get the strategy guide from Sybex! 0303 Part No. X09-58164 Safety Warning About Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confu- sion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures.