Drawing First Blood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Februarie Martie Aprilie Ianuarie Mai Iunie Iulie August

IANUARIE FEBRUARIE MARTIE APRILIE MAI 1 V △ Makoto Tomioka (1897), scriitorul socialist 1 L Apare revista Dacia Viitoare a Grupului Revoluționar 1 L Apare la New York primul număr din revista Mother 1 J △ Francisco Ascaso (1901); se încheie Războiul Civil 1 S Ziua internaȚională a muncii, muncitorilor și Constantin Mille (1862); începe rebeliunea zapatistă din Român (1883) Earth (1906), scoasă de Emma Goldman din Spania (1939) muncitoarelor; se deschide în București MACAZ - Bar regiunea Chiapas, Mexic (1994) 2 M Adolf Brand (1945); apare la București Dysnomia, 2 M scriitorul Philip K. Dick (1982) 2 V Zamfir C. Arbure (1933); Jandarmeria reprimă violent Teatru Coop., continuare a Centrului CLACA (2016) 2 S „Big Frank” Leech (1953) cerc de lectură feministă și queer (2015) 3 M △filosoful William Godwin (1756), feminista Milly pregătirea protestelor anti-NATO din București (2008) 2 D Gustav Landauer (1919); încep protestele 3 D △ Federico „Taino” Borrell Garcia (1912) 3 M △ coreean Pak Yol (1902), Simone Weil (1909) Witkop (1877); Lansare SexWorkCall la București (2019) 3 S △educator Paul Robin (1837); apare primul număr al studențești în Franța, cunoscute mai târziu ca „Mai ‘68” 4 L Albert Camus (1960); Revolta Spartachistă din 4 J △militantul Big Bill Heywood (1869) 4 J △ Suceso Portales Casamar (1904) revistei Strada din Timișoara (2017) 3 L △scriitorul Gérard de Lacaze-Duthiers (1958) Germania (1919) 5 V △ criticul Nikolai Dobroliubov (1836), Johann Most (1846); 5 V △socialista Rosa Luxemburg (1871) 4 D △militantul kurd Abdullah Öcalan (1949); 4 M Demonstrația din Piața Haymarket din Chicago (1886) 5 M △ Nelly Roussel (1878); Giuseppe Fanelli (1877), Auguste Vaillant (1894) 6 S Apare la Londra primul număr al revistei Anarchy (1968) 5 L Apare nr. -

The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism

“Glory of Yet Another Kind”: The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism, 1867-1924 GVGK Tang HIST4997: Honors Thesis Seminar Spring 2016 1 “What could you boast about except that you stifled my words, drowned out my voice . But I may enjoy the glory of yet another kind. I raised my voice in free and open protest against a thousand years of injustice.” —Karl Heinrich Ulrichs after being shouted down for protesting anti-sodomy laws in Munich, 18671 Queer* history evokes the familiar American narrative of the Stonewall Uprising and gay liberation. Most people know that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people rose up, like other oppressed minorities in the sixties, with a never-before-seen outpouring of social activism, marches, and protests. Popular historical discourse has led the American public to believe that, before this point, queers were isolated, fractured, and impotent – relegated to the shadows. The postwar era typically is conceived of as the critical turning point during which queerness emerged in public dialogue. This account of queer history depends on a social category only recently invented and invested with political significance. However, Stonewall was not queer history’s first political milestone. Indeed, the modern LGBT movement is just the latest in a series of campaign periods that have spanned a century and a half. Queer activism dawned with a new lineage of sexual identifiers and an era of sexological exploration in the mid-nineteenth century. German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs was first to devise a politicized queer identity founded upon sexological theorization.2 He brought this protest into the public sphere the day he outed himself to the five hundred-member Association 1 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, The Riddle of "Man-Manly" Love, trans. -

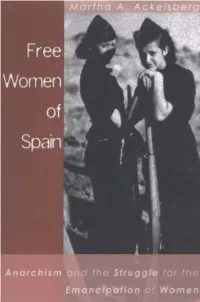

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

Ética, Anarquia E Revolução Em Maria Lacerda De Moura (Margareth Rago En Reis, Daniel Aarão E Ferreira, Jorge

1 Ética, Anarquia e Revolução em Maria Lacerda de Moura (Margareth Rago en Reis, Daniel Aarão e Ferreira, Jorge. As esquerdas no Brasil, vol. 1 A Formação das Tradições, 1889-1945. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2007, p. 262-293). “A vida não cabe dentro de um programa...” Maria Lacerda de Moura Se, ainda hoje, são reduzidos os nomes conhecidos das ativas militantes políticas de esquerda não só Brasil, é na história do movimento operário brasileiro que se encontra uma das mais importantes figuras do anarquismo: Maria Lacerda de Moura. Educadora libertária, escritora feminista, jornalista polêmica e oradora prestigiada, destaca-se por uma vibrante atuação nos meios políticos, culturais e literários brasileiros e sul-americanos, desde as primeiras décadas do século 20, quando se constitui o movimento operário, com a formação do mercado de trabalho livre, a industrialização e a vinda dos imigrantes europeus e de suas doutrinas políticas.1 Além dos inúmeros livros, artigos e folhetos em que denuncia as múltiplas formas da dominação burguesa, da opressão masculina e da exploração capitalista do trabalho, pesquisas recentes revelam que vários dos textos de Maria Lacerda de Moura podem ser encontrados não apenas nos periódicos brasileiros, mas também nas revistas anarquistas, publicadas na Espanha e na Argentina, entre as décadas de 1920 e 1930. Mesmo assim, apenas em 1984, vem a público a única biografia existente sobre ela, graças aos esforços da historiadora feminista Míriam Moreira Leite.2 A partir de então, sua figura ganha visibilidade para além do universo do 1 Veja-se Boris Fausto – Trabalho Urbano e Conflito Social. -

ASN6 Abstracts

1 ASN6 Abstracts Interactive Index Anarchist Responses to a Pandemic ............................................................ 1 (R)evolutionary Love in a Time of Crisis ....................................................... 1 Care and Crisis in New York: The Social Situation of Women, Anarcha- Feminism,and Mutual Aid During the COVID-19 Pandemic .......................... 2 Notes from the Unpaved Streets. Safety, Crisis, and Queer Autonomous Communities .............................................................................................. 2 Michel Foucault’s concept of political spirituality ........................................ 3 From apocalyptical to prophetical Eschatology. Anarchist understandings of temporality and revolutionary societal progress under conditions of everyday apocalypse ................................................................................... 4 Punk and Anarchy in Turkey: a complicated relationship ............................. 5 Out of Step: is Straight Edge Punk a post-anarchist movement? .................. 6 Anarchist counter-narratives through punk songs in conflict and post-conflict Northern Ireland, 1977-2020 ....................................................................... 7 Between Empires: An Anarchist and Postcolonial Critique of the 2019 Hong Kong Protests ............................................................................................. 7 Imperialism and Crisis (in Portuguese) ......................................................... 8 The Prevent Strategy and -

El Ysium Books

EL YS IUM BOOKS Shortlist #10 1. ALCIBIADE (Rocco, Antonio). Alcibiade Enfant a l'Ecole. Amsterdam and Paris: Aux depens d'une Socièté d'Amateurs [Marcel Seheur]. (1936). This uncommon and controversial text on ped- erasty bears an introduction by "Bramatos." The illustrations are not present. Pia 12. One of 250 hand numbered copies, this example #26. Very good in original salmon colored wrappers and contemporary 3/4 leather binding. Quite uncommon. $275. 2. ANONYMOUS. Circusz. [Budapest, c. 1940s]. 16to, 32 pp. An amusing collection of erot- ic circus acts, with rhyming text (in Hungarian). Most of the images involve assorted heterosexual couplings, but one image involves two male performers. Good in somewhat soiled illustrated wrappers, light wear. Undoubtedly an underground production that was only sold in limited numbers. Quite uncommon. $250. 3. ANONYMOUS. Guirlande de Priape. Texte et dessins par deux illustres médecins parisiens. A l'étal de gomorrhe, l'an de grace 1933. Sixteen erotic vignettes are accompanied by twenty quite explicit illus- trations by Jean Morisot. One of the texts is entitled "Soliloque de Corydon" and is attributed to "Victor Hugo." The twenty illustrations are ribald and encompass a range of sexual activities. One of 300 numbered copies. A very good example in original wrappers, chemise and slip- case, with only light wear. Dutel 1684. $250. 4. (ANONYMOUS). A Housemaster and His Boys (By one of them). London: Edward Arnold (1929). 120pp. First hand account of life in a boys school, with details on hazing, etc. Very good in mustard boards, lightly spotted. $120. 5. BERARD, Christian. -

The Anarchists: a Picture of Civilization at the Close of the Nineteenth Century

John Henry Mackay The Anarchists: A Picture of Civilization at the Close of the Nineteenth Century 1891 The Anarchist Library Contents Translator’s Preface ......................... 3 Introduction.............................. 4 1 In the Heart of the World-Metropolis .............. 6 2 The Eleventh Hour.......................... 21 3 The Unemployed ........................... 35 4 Carrard Auban ............................ 51 5 The Champions of Liberty ..................... 65 6 The Empire of Hunger........................ 87 “Revenge! Revenge! Workingmen, to arms! . 112 “Your Brothers.” ...........................112 7 The Propaganda of Communism..................127 8 Trafalgar Square ...........................143 9 Anarchy.................................153 Appendix................................164 2 Translator’s Preface A large share of whatever of merit this translation may possess is due to Miss Sarah E. Holmes, who kindly gave me her assistance, which I wish to grate- fully acknowledge here. My thanks are also due to Mr. Tucker for valuable suggestions. G. S. 3 Introduction The work of art must speak for the artist who created it; the labor of the thoughtful student who stands back of it permits him to say what impelled him to give his thought voice. The subject of the work just finished requires me to accompany it with a few words. *** First of all, this: Let him who does not know me and who would, perhaps, in the following pages, look for such sensational disclosures as we see in those mendacious speculations upon the gullibility of the public from which the latter derives its sole knowledge of the Anarchistic movement, not take the trouble to read beyond the first page. In no other field of social life does there exist to-day a more lamentable confusion, a more naïve superficiality, a more portentous ignorance than in that of Anarchism. -

Images of Androgyny in Germany at the Fin De Siecle

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 Blurring the Boundaries: Images of Androgyny in Germany at the Fin de Siecle Daniel James Casanova [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Casanova, Daniel James, "Blurring the Boundaries: Images of Androgyny in Germany at the Fin de Siecle. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1603 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Daniel James Casanova entitled "Blurring the Boundaries: Images of Androgyny in Germany at the Fin de Siecle." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. Monica Black, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Denise Phillips, Lynn Sacco Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Blurring the Boundaries: Images of Androgyny in Germany at the Fin de Siècle A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Daniel James Casanova May 2013 ii Dedication This work is gratefully dedicated to my family. -

Queer Mysticism: Elisàr Von Kupffer and the Androgynous Reform of Art Damien Delille

Queer Mysticism: Elisàr von Kupffer and the Androgynous Reform of Art Damien Delille To cite this version: Damien Delille. Queer Mysticism: Elisàr von Kupffer and the Androgynous Reform of Art. Between Light and Darkness – New Perspectives in Symbolism Research, Studies in the Long Nineteeth Century, vol. I, pp.45-57, 2014. halshs-01796704 HAL Id: halshs-01796704 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01796704 Submitted on 28 May 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DAMIEN DELILLE he dynamic rapport between science, Clarismus, von Kupffer and von Mayer sought to create a Queer Mysticism: psychology, esotericism, and sexuality that utopian ideal where male “over”-sexuality was deactivated. characterized cultural production at the turn At the intersection of esotericism and the dreamed antique, of the 20th century began to be recognized their proposal of an alternative male sexuality can thus be Elisàr von Kupffer inT the 1980s.1 This emergent scholarly literature, however, considered as an example of what I call “queer mysticism.”7 tended to focus on French and Belgian contexts, omitting A trans-historical aesthetic system, “queer mysticism” the contradictions found in parallel movements, such as combines the decompartmentalization of male and female and those in Germany.2 The artistic and theoretical practice genders and religious iconography. -

X Max Stirner

X MAX STIRNER In 1888 John Henry Mackay, the Scottish-German poet, while at the British Museum reading Lange's History of Materialism, encoimtered the name of Max Stirner and a brief criticism of his forgotten book, Der Einzige und sein Eigenthum (The Only One and His Property; in French translated L'Unique et sa Propri^te, and in the first English translation more aptly and euphoniously entitled The Ego and His Own). His curiosity excited, Mackay, who is an anarchist, procured after some difficulty a copy of the work, and so greatly was he stirred that for ten years he gave himself up to the study of Stimer and his teachings, and after incredible painstaking published in 1898 the story of his life. (Max Stimer: Sein Leben und sein Werk: John Henry Mackay.) To Mackay's labours we owe all we know of a man who was as absolutely swallowed up by the years as if he had never existed. But some advanced spirits had read Stirner's book, the most revolutionary ever written, and had felt its influence. Let us name two: Henrik Ibsen and Frederick Nietzsche. Though the name of Stirner is not quoted by Nietzsche, he nevertheless recommended Stirner to a favourite pupil of his, Professor Baumgartner at Basel University. This was in 1874. One hot August afternoon in the year 1896 at Bayreuth, I was standing in the Marktplatz when a member of the Wagner Theatre pointed out to me a house opposite, at the corner of the Maximilianstrasse, and said: "Do you see that house with the double gables? A man was born there whose name will be green when Jean Paul and Richard Wagner are forgotten." It was too large a draught upon my credulity, so I asked the name. -

Music Manuscripts and Books Checklist

THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM MASTERWORKS FROM THE MORGAN: MUSIC MANUSCRIPTS AND BOOKS The Morgan Library & Museum’s collection of autograph music manuscripts is unequaled in diversity and quality in this country. The Morgan’s most recent collection, it is founded on two major gifts: the collection of Mary Flagler Cary in 1968 and that of Dannie and Hettie Heineman in 1977. The manuscripts are strongest in music of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. Also, the Morgan has recently agreed to purchase the James Fuld collection, by all accounts the finest private collection of printed music in the world. The collection comprises thousands of first editions of works— American and European, classical, popular, and folk—from the eighteenth century to the present. The composers represented in this exhibition range from Johann Sebastian Bach to John Cage. The manuscripts were chosen to show the diversity and depth of the Morgan’s music collection, with a special emphasis on several genres: opera, orchestral music and concerti, chamber music, keyboard music, and songs and choral music. Recordings of selected works can be heard at music listening stations. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Der Schauspieldirektor, K. 486. Autograph manuscript of the full score (1786). Cary 331. The Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection. Mozart composed this delightful one-act Singspiel—a German opera with spoken dialogue—for a royal evening of entertainment presented by Emperor Joseph II at Schönbrunn, the royal summer residence just outside Vienna. It took the composer a little over two weeks to complete Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario). The slender plot concerns an impresario’s frustrated attempts to assemble the cast for an opera.