The Confederate Battle Flag, Texas High Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War Guide1

Produced by Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal Contents Teacher Guide 3 Activity 1: Billy Yank and Johnny Reb 6 Activity 2: A War Map 8 Activity 3: Young People in the Civil War 9 Timeline of the Civil War 10 Activity 4: African Americans in the Civil War 12 Activity 5: Writing a Letter Home 14 Activity 6: Political Cartoons 15 Credits Content: Barbara Glass, Glass Clarity, Inc. Newspaper Activities: Kathy Liber, Newspapers In Education Manager, The Cincinnati Enquirer Cover and Template Design:Gail Burt For More Information Border Illustration Graphic: Sarah Stoutamire Layout Design: Karl Pavloff,Advertising Art Department, The Cincinnati Enquirer www.libertyontheborder.org Illustrations: Katie Timko www.cincymuseum.org Photos courtesy of Cincinnati Museum Center Photograph and Print Collection Cincinnati.Com/nie 2 Teacher Guide This educational booklet contains activities to help prepare students in grades 4-8 for a visit to Liberty on the Border, a his- tory exhibit developed by Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal.The exhibit tells the story of the American Civil War through photographs, prints, maps, sheet music, three-dimensional objects, and other period materials. If few southern soldiers were wealthy Activity 2: A War Map your class cannot visit the exhibit, the slave owners, but most were from activity sheets provided here can be used rural agricultural areas. Farming was Objectives in conjunction with your textbook or widespread in the North, too, but Students will: another educational experience related because the North was more industri- • Examine a map of Civil War America to the Civil War. Included in each brief alized than the South, many northern • Use information from a chart lesson plan below, you will find objectives, soldiers had worked in factories and • Identify the Mississippi River, the suggested class procedures, and national mills. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Flag Research Quarterly, August 2016, No. 10

FLAG RESEARCH QUARTERLY REVUE TRIMESTRIELLE DE RECHERCHE EN VEXILLOLOGIE AUGUST / AOÛT 2016 No. 10 DOUBLE ISSUE / FASCICULE DOUBLE A research publication of the North American Vexillological Association / Une publication de recherche de THE FLAGS AND l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie SEALS OF TEXAS A S I LV E R A NN I V E R S A R Y R E V I S I O N Charles A. Spain I. Introduction “The flag is the embodiment, not of sentiment, but of history. It represents the experiences made by men and women, the experiences of those who do and live under that flag.” Woodrow Wilson1 “FLAG, n. A colored rag borne above troops and hoisted on forts and ships. It appears to serve the same purpose as certain signs that one sees on vacant lots in London—‘Rubbish may be shot here.’” Ambrose Bierce2 The power of the flag as a national symbol was all too evident in the 1990s: the constitutional debate over flag burning in the United States; the violent removal of the communist seal from the Romanian flag; and the adoption of the former czarist flag by the Russian Federation. In the United States, Texas alone possesses a flag and seal directly descended from revolution and nationhood. The distinctive feature of INSIDE / SOMMAIRE Page both the state flag and seal, the Lone Star, is famous worldwide because of the brief Editor’s Note / Note de la rédaction 2 existence of the Republic of Texas (March 2, 1836, to December 29, 1845).3 For all Solid Vexillology 2 the Lone Star’s fame, however, there is much misinformation about it. -

VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 MARCH—MAY, 2010 IRISHMAN of the YEAR the Louisiana State Board of Federal Narcotics Enforcement the Ancient Order of Hiber- Taskforce

THE CRESCENT HARP THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN LOUISIANA VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 MARCH—MAY, 2010 IRISHMAN OF THE YEAR The Louisiana State Board of Federal Narcotics Enforcement the Ancient Order of Hiber- taskforce. Upon his retire- nians, Philip M. Hannan, Car- ment from the Police Depart- dinal Gibbons, Acadian, and ment, he has continued to Republic of West Florida Divi- serve on the board of the Po- sions proudly announce Joseph lice Federal Credit Union. James Cronin Sr. as Irishman Cronin is a member of the of the Year for 2010. A re- Veterans of Foreign Wars Post FOLLOW THE LOUISIANA tired longshoreman and vet- 6640 and American Legion AOH ON-LINE eran of the New Orleans Po- Post 267. He is a parishioner www.aohla.com lice Department, Brother Cro- at St. Benilde Church in Met- FACEBOOK nin was born in New Orleans airie where he was recently Louisiana State Board of in 1924, the son of the late honoured as a senior great- the Ancient Order of Hibernians Michael R. Cronin and Alice grandfather. McMullen Cronin. A native of Cronin was married to the UPCOMING EVENTS: the Irish Channel, he attended Navy Seabees from 1943-46. late Hilda Conzonire Cronin Redemptorist School and is a Upon his return from the from 1942 to 1960 and is cur- Irish Channel 1943 graduate of St. Aloysius war, Cronin joined the Clerks rently married to the former St. Patrick’s Day High School where he was Local Longshoreman’s Union Judy Whitney since 1963. He Mass and Parade named second team All-Prep Number 1497 and then gradu- is the father of six children, SATURDAY, MARCH 13 as a member of the football ated from the New Orleans twelve grandchildren, and two 12 noon team. -

Mammy Figure

Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory Kimberly Wallace-Sanders http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=170676 The University of Michigan Press INTRODUCTION The “Mammi‹cation” of the Nation: Mammy and the American Imagination Nostalgia is best de‹ned as a yearning for that which we know we have destroyed. —david blight The various incarnations of the mammy ‹gure have had a profound in›uence on American culture. There is virtually no medium that has not paid homage to the mammy in some form or another. In his series “Ameri- can Myths,”for example, artist Andy Warhol included both the mammy and Aunt Jemima, along with Howdy Doody, Uncle Sam, Dracula, and the Wicked Witch of the West (‹gs. 1 and 2).1 In the late 1980s, Italian pho- tographer Olivero Toscani created an advertisement for Benetton featuring a close-up of a white infant nursing at the breast of a headless, dark- skinned black woman wearing a red Shetland sweater (‹g. 3). The adver- tisement was met with unbridled criticism from African Americans, yet it won more advertising awards than any other image in Benetton’s advertis- ing history.2 Today, tourists visiting Lancaster, Kentucky, can tour the for- mer slave plantation of Governor William Owsley, ironically called Pleas- ant Retreat. The restored home features many remnants of the Old South, including a “charming mammy bench,” a combination rocking chair and cradle designed to allow mammies to nurse an infant and rock an additional baby at the same time.3 Diminutive mammy “nipple dolls” made in the 1920s from rubber bottle nipples with tiny white baby dolls cradled in their arms are both a “well-kept secret”and an excellent investment by collectors of southern Americana (‹g. -

A Southern Belle Goes North a Southern Belle Goes North A

A Southern Belle Goes North Virgie Mueller A Southern Belle Goes North Virgie Mueller “Let each generation tell its children Of your mighty acts; Let them proclaim your power. I will meditate on your majestic splendor And your wonderful miracles Your awe-inspiring deeds will be on every tongue; I will proclaim your greatness. Everyone will share the story Of your wonderful goodness; They will sing with joy about your righteousness.” A SOUTHERN BELLE GOES NORTH Psalm 145:4-7 Copyright © 2014 by Virgie A. Mueller All rights reserved. No part of this publication my be reproduced without permission. Design and layout – Northern Canada Mission Press ISBN: 978-0-9938923 Printed in Canada Dedication To our children: Steven Mueller, Glen Mueller, and Sheryl Mueller Giesbrecht, who have journeyed with us on paths not necessarily of their choosing, I dedicate this book. They say they have no regrets of being raised on the mission field. God has blessed them and kept them and today they are Godly parents and grandparents. They have raised children who also love the Lord. And To our grandchildren: Tyler Mueller, Rashel Giesbrecht Pilon, Stephanie Mueller Baerg, Graeme Mueller, Joel Giesbrecht, Colton Mueller, Hannah Mueller and Caleb Mueller I dedicate this book. “The Lord bless you and keep you. The Lord make His face shine upon you and be gracious to you; the Lord turn His face toward you and give you peace.” Numbers 6:24-26 Table of Contents Part 1 A Memoir: The Years in Paint Hills, Quebec 1962-1968 The Story of Chapter 1 - The Unknown . -

Six Flags of Texas

SIX FLAGS OF TEXAS 1685–1689 French flag possibly used by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, during the French colonization of Texas 1690–1785 State flag and ensign of New Spain, also known as the Cross of Burgundy flag 1785–1820 Spanish state flag on land 1821–1823 Flag of the first Mexican Empire 1823–1836 First flag of the Mexican Republic, flown over soil claimed by Mexico until the Texas Revolution 1836–1839; 1839–1879 The "Burnet Flag," used from December 1836 to 1839 as the national flag of the Republic of Texas until it was replaced by the currently used "Lone Star Flag"; it was the de jure war flag from then until 1879 1839–1845/1846 Republic of Texas national flag from 1839-1845/1846 (identical to modern state flag) 1845–1861, 1865–present US flag in 1846 when Texas became part of the Union 1861–1865 CS flag in 1861 when Texas became a part of the Confederacy (for further CS flags, see CS flag: National flags) Secession flags of Texas, 1861[ In early 1861, between the secession of Texas from the U.S. and its accession to the Confederacy, Texas flew an unofficial, variant flag of Texas with fifteen stars, representing the fifteen states. No drawings exist of the flag, there are only imprecise descriptions. The flag may have been based on the state flag or the Bonnie Blue Flag.[23] Possible secession flag based on the state flag Possible secession flag based on the Bonnie Blue Flag State flag over Texas 1845–present Flag of the State of Texas in the United States of America TH BATTLE FLAG OF THE 4 TEXAS The 4th Texas carried two different battle flags during the Civil War. -

Texas Co-Op Power • December 2019

1912_local covers black.qxp 11/12/19 7:54 AM Page 5 COMANCHE ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE DECEMBER 2019 Origins of the Lone Star Nixon vs. Co-ops Desert Vistas Tamale Time The making—and eating—of tamales signals the start of the season Since 1944 December 2019 FAVORITES The blueprint for Texas’ 5 Letters iconic lone star is some- what of a mystery. 6 Currents 18 Co-op News Get the latest information plus energy and safety tips from your cooperative. 29 Texas History Nixon’s Attack on Co-ops By Ellen Stader 31 Retro Recipes Cookies & Candies 35 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Deserts 36 Around Texas List of Local Events 38 Hit the Road Camp Street Blues By Chet Garner ONLINE TexasCoopPower.com Find these stories online if they don’t FEATURES appear in your edition of the magazine. Texas USA A Star Is Born Texas’ iconic lone star may trace its origins The Southwestern Tempo 8 to 1817 Mexican coins. Excerpt by J. Frank Dobie By Clay Coppedge Observations Lazarus the Bug The Call of the Tamalada Making tamales is a holiday By Sheryl Smith-Rodgers 10 tradition, though eating them never ends. Story by Eileen Mattei | Photos by John Faulk NEXT MONTH Texas Feels a Draft Craft breweries bring entertainment and economic opportunity to communities. 31 38 29 35 STAR: JACK MOLLOY. BEER: MAXY M | SHUTTERSTOCK.COM ON THE COVER Celia Galindo helps continue a tamalada tradition started by her grandmother in 1949 in Brownsville. Photo by John Faulk TEXAS ELECTRIC COOPERATIVES BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Alan Lesley, Chair, Comanche; Robert Loth III, Vice Chair, Fredericksburg; Gary Raybon, Secretary-Treasurer, El Campo; Mark Boyd, Douglassville; Greg Henley, Tahoka; Billy Jones, Corsicana; David McGinnis, Van Alstyne • PRESIDENT/CEO: Mike Williams, Austin • COMMUNICATIONS & MEMBER SERVICES COMMITTEE: Marty Haught, Burleson; Bill Hetherington, Bandera; Ron Hughes, Sinton; Boyd McCamish, Littlefield; Mark McClain, Roby; John Ed Shinpaugh, Bonham; Robert Walker, Gilmer; Brandon Young, McGregor • MAGAZINE STAFF: Martin Bevins, Vice President, Communications & Member Services; Charles J. -

SUB FINAL RANK TEAM NAME CITY TOTAL Point Safety SCORE 1 San Angelo Central High School San Angelo 72.500 0.00 0.00 72.500 2 Jo

Texas State Spirit Championships - Preliminary Round January 1, 2016 FIGHT SONG- 6A (Out of 80 possible points) SUB DEDUCTIONS FINAL RANK TEAM NAME CITY TOTAL Point Safety SCORE 1 San Angelo Central High School San Angelo 72.500 0.00 0.00 72.500 2 John Horn High School Mesquite 72.400 0.00 0.00 72.400 3 Johnson High School San Antonio 70.533 0.50 0.00 70.033 4 Carroll Senior High School Southlake 69.533 0.00 0.00 69.533 5 Canyon High School New Braunfels 68.333 0.00 0.00 68.333 6 Flower Mound High School Flower Mound 67.967 0.00 0.00 67.967 7 McAllen Memorial High School McAllen 67.733 0.00 0.00 67.733 8 Oak Ridge High School Conroe 67.300 0.00 0.00 67.300 9 Dickinson High School Dickinson 65.300 0.00 0.00 65.300 10 Friendswood High School Friendswood 70.200 0.00 5.00 65.200 11 Keller Central High School Keller 65.100 0.00 0.00 65.100 12 Colleyville Heritage High School Colleyville 64.967 0.00 0.00 64.967 13 Pearland High School Pearland 64.867 0.00 0.00 64.867 14 West Brook High School Beaumont 64.733 0.00 0.00 64.733 15 Timber Creek High School Keller 63.767 0.00 0.00 63.767 16 Allen High School Allen 63.733 0.00 0.00 63.733 17 Clear Lake High School Houston 63.533 0.00 0.00 63.533 18 McKinney Boyd High School McKinney 63.200 0.00 0.00 63.200 19 Cypress Falls High School Houston 62.767 0.00 0.00 62.767 20 Montgomery High School Montgomery 62.500 0.00 0.00 62.500 21 Midlothian High School Midlothian 62.467 0.00 0.00 62.467 22 Byron Nelson High School Trophy Club 62.367 0.00 0.00 62.367 23 Cypress Ranch High School Cypress 61.733 0.00 -

New Orleans in 1810

New Orleans in 1810 As the Crescent City begins a new decade, it is worthwhile exploring what this glittering gem on the Mississippi was like 210 years ago. 1810 marked seven years after the Louisiana Purchase but two years before Louisiana achieved statehood. The city of Memphis, Tennessee, was not yet founded until nearly a decade later. In fact, that summer was the first public celebration of the Fourth of July in Louisiana at the St. Philip Theatre (Théâtre St. Philippe). Built in 1807 on St. Phillip Street, between Royal and Bourbon streets, the theatre could accommodate 700 people. With a parquette and two rows of boxes, the Théâtre St. Philippe was the rendezvous of all the fashionable people of New Orleans. The gala performance held that July 4, 1810, was in honor of the Declaration of Independence and the proceeds were devoted to the relief of victims of a giant fire on July 1 that had destroyed twenty-five houses. Haitian rebels battle the French in the Saint-Domingue Revolution (1791 – 1804) The revolution in Saint-Domingue brought about the second republic in the Western Hemisphere. Not all were happy or safe with the new leadership, and many Haitian refugees would make their way to New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites (affranchis), 3,102 free persons of African descent (gens de couleur libres) and 3,226 slaves to the city. While Governor Claiborne and other American officials wanted to prevent the arrival of free black émigrés, French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. In a few months between 1809 and 1810, 10,000 Saint-Domingue refugees poured into the Territory of Orleans, after they were no longer welcome in Cuba. -

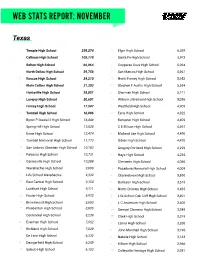

Web Stats Report: November

WEB STATS REPORT: NOVEMBER Texas 1 Temple High School 259,274 31 Elgin High School 6,029 2 Calhoun High School 108,778 32 Santa Fe High School 5,973 3 Belton High School 66,064 33 Copperas Cove High School 5,964 4 North Dallas High School 59,756 34 San Marcos High School 5,961 5 Roscoe High School 34,210 35 North Forney High School 5,952 6 Klein Collins High School 31,303 36 Stephen F Austin High School 5,554 7 Huntsville High School 28,851 37 Sherman High School 5,211 8 Lovejoy High School 20,601 38 William J Brennan High School 5,036 9 Forney High School 17,597 39 Westfield High School 4,909 10 Tomball High School 16,986 40 Early High School 4,822 11 Byron P Steele I I High School 16,448 41 Kempner High School 4,809 12 Spring Hill High School 13,028 42 C E Ellison High School 4,697 13 Ennis High School 12,474 43 Midland Lee High School 4,490 14 Tomball Memorial High School 11,773 44 Odem High School 4,470 15 San Antonio Christian High School 10,783 45 Gregory-Portland High School 4,299 16 Palacios High School 10,731 46 Hays High School 4,235 17 Gainesville High School 10,288 47 Clements High School 4,066 18 Waxahachie High School 9,609 48 Pasadena Memorial High School 4,009 19 Life School Waxahachie 9,332 49 Channelview High School 3,890 20 East Central High School 9,150 50 Burleson High School 3,615 21 Lockhart High School 9,111 51 North Crowley High School 3,485 22 Foster High School 8,972 52 Life School Oak Cliff High School 3,401 23 Brownwood High School 8,803 53 L C Anderson High School 3,400 24 Pleasanton High School 8,605 54 Samuel -

To Better Serve and Sustain the South: How Nineteenth Century

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons at Buffalo State State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State History Theses History and Social Studies Education 8-2012 To Better Serve and Sustain the South: How Nineteenth Century Domestic Novelists Supported Southern Patriarchy Using the "Cult of True Womanhood" and the Written Word Daphne V. Wyse Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Jean E. Richardson, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History First Reader Michael S. Pendleton, Ph. D., Associate Professor of Political Science Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls, Ph.D., Professor of History To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Wyse, Daphne V., "To Better Serve and Sustain the South: How Nineteenth Century Domestic Novelists Supported Southern Patriarchy Using the "Cult of True Womanhood" and the Written Word" (2012). History Theses. Paper 8. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/history_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Abstract During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, American women were subjected to restrictive societal expectations, providing them with a well-defined identity and role within the male- dominated culture. For elite southern women, more so than their northern sisters, this identity became integral to southern patriarchy and tradition. As the United States succumbed to sectional tension and eventually civil war, elite white southerners found their way of life threatened as the delicate web of gender, race, and class relations that the Old South was based upon began to crumble.