Provisional Findings Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAJAR Comparative Report Q3 2003

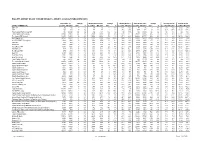

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 3 2003/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share LOCAL COMMERCIAL Last Pub W3 2003 000's % Last Pub W3 2003 000's % Last Pub W3 2003 Last Pub W3 2003 000's % Last Pub W3 2003 Last Pub W3 2003 Bath FM 82 82 0 0% 16 15 -1 -6% 19% 19% 88 95 7 8% 5.6 6.3 5.5% 5.8% 2BR 203 203 0 0% 77 78 1 1% 38% 38% 799 826 27 3% 10.3 10.6 18.3% 18.8% Total Capital Radio Group UK n/p 48384 n/a n/a n/p 7756 n/a n/a n/p 16% n/p 71888 n/a n/a n/p 9.3 n/p 6.8% Total Capital Radio Group 28097 28081 -16 0% 7600 7630 30 0% 27% 27% 70870 71265 395 1% 9.3 9.3 11.8% 11.9% The Capital FM Network 18951 18951 0 0% 5090 5016 -74 -1% 27% 26% 42282 41373 -909 -2% 8.3 8.2 10.3% 10.2% 95.8 Capital FM 10344 10343 -1 0% 2624 2269 -355 -14% 25% 22% 18991 15613 -3378 -18% 7.2 6.9 8.9% 7.0% 96.4 FM BRMB Birmingham 2004 2004 0 0% 588 555 -33 -6% 29% 28% 4339 4456 117 3% 7.4 8.0 9.8% 10.2% FOX FM 558 559 1 0% 208 214 6 3% 37% 38% 2289 2354 65 3% 11.0 11.0 19.2% 19.5% Invicta FM 1075 1075 0 0% 425 438 13 3% 39% 41% 4634 4984 350 8% 10.9 11.4 17.0% 18.3% 103.2 Power FM 1066 1066 0 0% 299 277 -22 -7% 28% 26% 2624 2326 -298 -11% 8.8 8.4 10.2% 9.7% Southern FM 949 949 0 0% 356 332 -24 -7% 38% 35% 4218 3679 -539 -13% 11.9 11.1 17.4% 16.3% Red Dragon FM 889 889 0 0% 301 311 10 3% 34% 35% 2789 2570 -219 -8% 9.3 8.3 13.3% 12.8% Beat 106 2599 2599 0 0% 415 447 32 8% 16% 17% 2976 3490 514 17% 7.2 7.8 5.8% 7.0% Beat 106 (East) 1101 1101 0 0% 199 198 -1 -1% 18% -

Domain Stationid Station UDC Performance Date

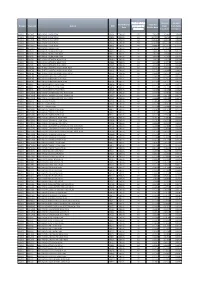

Number of days Amount Amount Performance Total Per Domain StationId Station UDC processed for from from Public Date Minute Rate distribution Broadcast Reception RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 NON PEAK BRA01 CENSUS 92 7.8347 4.2881 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 LOW PEAK BRB01 CENSUS 92 10.7078 7.1612 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 HIGH PEAK BRC01 CENSUS 92 13.5380 9.9913 3.5466 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 NON PEAK BRA02 CENSUS 92 17.4596 11.2373 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 LOW PEAK BRB02 CENSUS 92 24.9887 18.7663 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 HIGH PEAK BRC02 CENSUS 92 32.4053 26.1830 6.2223 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA NON PEAK BRA10 CENSUS 92 1.4814 1.4075 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA LOW PEAK BRB10 CENSUS 92 2.4245 2.3506 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA HIGH PEAK BRC10 CENSUS 92 3.3534 3.2795 0.0739 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK NON PEAK BRA65 CENSUS 92 1.4691 1.4593 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK LOW PEAK BRB65 CENSUS 92 2.4468 2.4371 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK HIGH PEAK BRC65 CENSUS 92 3.4100 3.4003 0.0098 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO NON PEAK BRA62 CENSUS 92 0.1516 0.1104 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO LOW PEAK BRB62 CENSUS 92 0.2256 0.1844 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO HIGH PEAK BRC62 CENSUS 92 0.2985 0.2573 0.0411 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE NON PEAK BRA64 CENSUS 92 0.0803 0.0569 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE LOW PEAK BRB64 CENSUS 92 0.1184 0.0951 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE HIGH PEAK BRC64 CENSUS 92 0.1560 0.1327 0.0233 RADIO BRBRIS BBC -

Laissez-Faire Regulation, the Public Spending Squeeze and the Drive to Digital Guy Starkey*

Cultural Trends, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2014.1000591 COMMENTARY 5 Cultural policy in the coalition years: Laissez-faire regulation, the public spending squeeze and the drive to digital Guy Starkey* 10 Centre for Research in Media & Cultural Studies, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, UK Introduction Radio, so often described by academics as the “invisible” (Lewis & Booth, 1989), “Cinder- ” – “ ” 15 ella (Halesworth, 1971, pp. 189 191) or even forgotten medium (Pease & Dennis, 1994), has enjoyed a relatively settled period under the coalition government. There has been no crisis of confidence over ethical and legal issues, as exposed in the press by Leveson and the police operations, Elveden, Tuleta and Weeting. There have been few head- line-grabbing (if difficult-to-evaluate) initiatives like local television, as exemplified by London Live or Made in Tyne & Wear, and no government-rocking conflicts of interest as 20 spectacular as that over the ownership of BSkyB. Nor indeed has there been any game-chan- ging reorganisation of public funding, similar to the Arts Council’s lists of winners and losers. Yet, as is so often the case, radio remains a significant, but largely, ignored medium. In terms of government policy, it has suffered mixed fortunes under the five years of the coalition. Official listening figures continue to confirm recent trends in radio’s fortunes. If radio grabs 25 little of the media limelight, it remains a medium with an enviable ubiquity. It may have been slow to win audiences among younger people as large as when it broke new music and pro- vided the kind of escapism sought by youth in the 1960s and 1970s. -

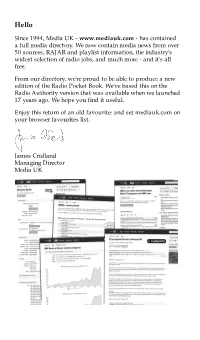

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

QUARTERLY SUMMARY of RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 24Th June 2012

QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 24th June 2012 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 52,352,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period '000 % per head per listener '000 TSA % ALL RADIO Q 46782 89 19.7 22.1 1032842 100.0 ALL BBC Q 34444 66 10.7 16.3 560644 54.3 ALL BBC 15-44 Q 15286 61 7.1 11.7 178688 42.1 ALL BBC 45+ Q 19158 71 14.1 19.9 381956 62.7 All BBC Network Radio1 Q 31454 60 9.1 15.2 476843 46.2 BBC Local/Regional Q 8962 17 1.6 9.4 83801 8.1 ALL COMMERCIAL Q 33182 63 8.5 13.5 446834 43.3 ALL COMMERCIAL 15-44 Q 17952 71 9.2 12.9 232228 54.8 ALL COMMERCIAL 45+ Q 15231 56 7.9 14.1 214606 35.3 All National Commercial1 Q 16101 31 2.5 8.2 131542 12.7 All Local Commercial (National TSA) Q 26364 50 6.0 12.0 315292 30.5 Other Listening Q 3387 6 0.5 7.5 25363 2.5 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI/RSMB 1 See note on back cover. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Embargoed until 00.01 am Enquires to: RAJAR, 6th floor, 55 New Oxford St, London WC1A 1BS 2nd August 2012 Telephone: 020 7395 0630 Facsimile: 020 7395 0631 e mail: [email protected] Internet: www.rajar.co.uk ©Rajar 2012. -

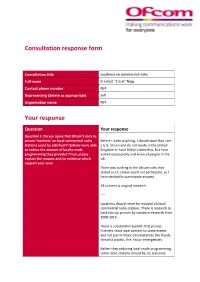

Localness on Commercial Radio Full Name Erzsebet “Erzsie” Nagy Contact Phone Number N/A Representing (Delete As Appropriate) Self Organisation Name N/A

Consultation response form Consultation title Localness on commercial radio Full name Erzsebet “Erzsie” Nagy Contact phone number N/A Representing (delete as appropriate) Self Organisation name N/A Your response Question Your response Question 1: Do you agree that Ofcom’s duty to secure ‘localness’ on local commercial radio Before I write anything, I should state that I am stations could be satisfied if stations were able a U.S. citizen and do not reside in the United to reduce the amount of locally-made Kingdom or have British citizenship, but have programming they provide? If not, please visited occasionally and know of people in the explain the reasons and/or evidence which UK. support your view. There was nothing in the Ofcom rules that stated a U.S. citizen could not participate, so I have decided to participate anyway. All content is original research. ---- Localness should never be reduced on local commercial radio stations. There is research to back this up, proven by statistical research from 2008-2014. There is substantial research that proves listeners value local content to some extent, and not just in major circumstances like floods, terrorist attacks, fire, major emergencies. Rather than reducing local-made programming, some radio stations should be, by statutory requirement, have as much local programming and content as necessary. There is substantial evidence from American researchers – 2004, 2008, 2012, 2014 that proved listeners value locality as a major selling point. Unofficial research in 2007 has proved this. No station should be local for only 3 hours a day, whatever the day of week. -

Free Radio 80S (Coventry, Wolverhampton1 and Birmingham)

Section 355 Review of Output: Free Radio 80s (Coventry, Wolverhampton1 and Birmingham) When a local commercial radio licence undergoes a change of control (this includes licence transfer), Ofcom is required, under section 355 of the Communications Act 2003 (the Act), to undertake a review of the effects or likely effects of the change of control in relation to: the quality and range of programmes included in the service; the character of the service, and; the extent to which Ofcom’s duty under section 314 of the Act is performed in relation to the service. Ofcom’s duty under section 314 of the Act relates to securing the inclusion of an appropriate amount of local material, and a suitable proportion of locally-made programmes in the service. Under section 356 of the Act, where it appears to Ofcom from its review that the change of control would be prejudicial to any of the three matters listed above, then it must vary the licence, by including such conditions as it considers appropriate, with a view to ensuring that the relevant change of control is not so prejudicial. In doing so, any new or varied conditions must be such that the licence holder would have satisfied them throughout the three months immediately before the change of control. Ofcom is required to publish a report of its review, setting out its conclusions and any steps it proposes to take under section 356. Where Ofcom proposes to vary the licence, it is required to give the licence holder a reasonable opportunity to make representations about the variation. -

Radio/Audio Slides for CMR11

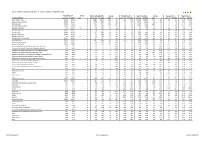

3. Radio and audio 0 Figure 3.1 UK radio industry key metrics UK radio industry 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Weekly reach of radio (% of population) 90.0% 89.8% 89.8% 89.5% 89.8% 90.6% Average weekly hours per head 21.6 21.2 20.6 20.1 19.8 20.1 BBC share of listening 54.5% 54.7% 55.0% 55.7% 55.3% 55.2% Total industry revenue £1,118m £1,126m £1,174m £1,137m £1,092m £1,123m Commercial revenue £530m £512m £522m £488m £432m £438m BBC expenditure £588m £614m £652m £649m £660m £685m Radio share of advertising spend 3.3% 3.0% 2.9% 2.8% 2.8% 2.7% DAB digital radio take-up (households) 11.1% 16.0% 22.3% 29.7% 33.4% 35.8% Source: RAJAR (all adults age 15+), Ofcom calculations based on figures in BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2010/11 note 2c (www.bbc.co.uk/annualreport), AA/Warc, broadcasters. Revenue figures are nominal. Figure 3.2 Radio industry revenue and spending 2005-2010 £ million 1174 1200 1118 1126 1137 1092 1123 1000 522 438 Total commercial 530 512 488 432 800 600 400 652 649 660 685 BBC expenditure 588 614 (estimated) 200 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Source: Ofcom / operator data / BBC Annual Report 2005-2010 Note: BBC expenditure figures are estimated by Ofcom based on figures in Note 2c of the BBC Annual Report (www.bbc.co.uk/annualreport); figures in the chart are rounded and are nominal. -

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 3 2019/Last Published Data

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 3 2019/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share STATION/GROUP Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 Bauer Radio - Total 55032 55032 0 0% 18083 18371 288 2% 33% 33% 156216 158995 2779 2% 8.6 8.7 15.3% 15.9% Absolute Radio Network 55032 55032 0 0% 4743 4921 178 4% 9% 9% 35474 35522 48 0% 7.5 7.2 3.5% 3.6% Absolute Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 2151 2447 296 14% 4% 4% 16402 17626 1224 7% 7.6 7.2 1.6% 1.8% Absolute Radio (London) 12260 12260 0 0% 729 821 92 13% 6% 7% 4279 4370 91 2% 5.9 5.3 2.1% 2.2% Absolute Radio 60s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 125 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 298 n/a n/a n/p 2.4 n/p *% Absolute Radio 70s 55032 55032 0 0% 206 208 2 1% *% *% 699 712 13 2% 3.4 3.4 0.1% 0.1% Absolute 80s 55032 55032 0 0% 1779 1824 45 3% 3% 3% 9294 9435 141 2% 5.2 5.2 0.9% 1.0% Absolute Radio 90s 55032 55032 0 0% 907 856 -51 -6% 2% 2% 4008 3661 -347 -9% 4.4 4.3 0.4% 0.4% Absolute Radio 00s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 209 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 540 n/a n/a n/p 2.6 n/p 0.1% Absolute Radio Classic Rock 55032 55032 0 0% 741 721 -20 -3% 1% 1% 3438 3703 265 8% 4.6 5.1 0.3% 0.4% Hits Radio Brand 55032 55032 0 0% 6491 6684 193 3% 12% 12% 53184 54489 1305 2% 8.2 8.2 5.2% 5.5% Greatest Hits Network 55032 55032 0 0% 1103 1209 106 10% 2% 2% 8070 8435 365 5% 7.3 7.0 0.8% 0.8% Greatest Hits Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 715 818 103 14% 1% 1% 5281 5870 589 11% 7.4 7.2 0.5% -

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 1 2020/Last Published Data

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 1 2020/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share STATION/GROUP Last Pub W1 2020 000's % Last Pub W1 2020 000's % Last Pub W1 2020 Last Pub W1 2020 000's % Last Pub W1 2020 Last Pub W1 2020 Bauer Radio - Total 55032 55032 0 0% 18160 17986 -174 -1% 33% 33% 155537 154249 -1288 -1% 8.6 8.6 15.9% 15.7% Absolute Radio Network 55032 55032 0 0% 4908 4716 -192 -4% 9% 9% 34837 33647 -1190 -3% 7.1 7.1 3.6% 3.4% Absolute Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 2309 2416 107 5% 4% 4% 16739 18365 1626 10% 7.3 7.6 1.7% 1.9% Absolute Radio (London) 12260 12260 0 0% 715 743 28 4% 6% 6% 5344 5586 242 5% 7.5 7.5 2.7% 2.8% Absolute Radio 60s 55032 55032 0 0% 136 119 -17 -13% *% *% 359 345 -14 -4% 2.6 2.9 *% *% Absolute Radio 70s 55032 55032 0 0% 212 230 18 8% *% *% 804 867 63 8% 3.8 3.8 0.1% 0.1% Absolute 80s 55032 55032 0 0% 1420 1459 39 3% 3% 3% 7020 7088 68 1% 4.9 4.9 0.7% 0.7% Absolute Radio 90s 55032 55032 0 0% 851 837 -14 -2% 2% 2% 3518 3593 75 2% 4.1 4.3 0.4% 0.4% Absolute Radio 00s 55032 55032 0 0% 217 186 -31 -14% *% *% 584 540 -44 -8% 2.7 2.9 0.1% 0.1% Absolute Radio Classic Rock 55032 55032 0 0% 740 813 73 10% 1% 1% 4028 4209 181 4% 5.4 5.2 0.4% 0.4% Hits Radio Brand 55032 55032 0 0% 6657 6619 -38 -1% 12% 12% 52607 52863 256 0% 7.9 8.0 5.4% 5.4% Greatest Hits Network 55032 55032 0 0% 1264 1295 31 2% 2% 2% 9347 10538 1191 13% 7.4 8.1 1.0% 1.1% Greatest Hits Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 845 892 47 6% 2% 2% 6449 7146 697 11% 7.6 8.0 0.7% -

"It's Aimed at Kids - the Kid in Everybody": George Lucas, Star Wars and Children's Entertainment by Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia, UK

"It's aimed at kids - the kid in everybody": George Lucas, Star Wars and Children's Entertainment By Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia, UK When Star Wars was released in May 1977, Time magazine hailed it as "The Year's Best Movie" and characterised the special quality of the film with the statement: "It's aimed at kids - the kid in everybody" (Anon., 1977). Many film scholars, highly critical of the aesthetic and ideological preoccupations of Star Wars and of contemporary Hollywood cinema in general, have elaborated on the second part in Time magazine's formula. They have argued that Star Wars is indeed aimed at "the kid in everybody", that is it invites adult spectators to regress to an earlier phase in their social and psychic development and to indulge in infantile fantasies of omnipotence and oedipal strife as well as nostalgically returning to an earlier period in history (the 1950s) when they were kids and the world around them could be imagined as a better place. For these scholars, much of post-1977 Hollywood cinema is characterised by such infantilisation, regression and nostalgia (see, for example, Wood, 1985). I will return to this ideological critique at the end of this essay. For now, however, I want to address a different set of questions about production and marketing strategies as well as actual audiences: What about the first part of Time magazine's formula? Was Star Wars aimed at children? If it was, how did it try to appeal to them, and did it succeed? I am going to address these questions first of all by looking forward from 1977 to the status Star Wars has achieved in the popular culture of the late 1990s. -

Bauer Media Group Phase 1 Decision

Completed acquisitions by Bauer Media Group of certain businesses of Celador Entertainment Limited, Lincs FM Group Limited and Wireless Group Limited, as well as the entire business of UKRD Group Limited Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6809/19; ME/6810/19; ME/6811/19; and ME/6812/19 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 22(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 24 July 2019. Full text of the decision published on 30 August 2019. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties or third parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. Between 31 January 2019 and 31 March 2019 Heinrich Bauer Verlag KG (trading as Bauer Media Group (Bauer)), through subsidiaries, bought: (a) From Celador Entertainment Limited (Celador), 16 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences (the Celador Acquisition); (b) From Lincs FM Group Limited (Lincs), nine local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, a [] interest in an additional local radio station and associated licences, and interests in the Lincolnshire [] and Suffolk [] digital multiplexes (the Lincs Acquisition); (c) From The Wireless Group Limited (Wireless), 12 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, as well as digital multiplexes in Stoke, Swansea and Bradford (the Wireless Acquisition); and (d) The entire issued share capital of UKRD Group Limited (UKRD) and all of UKRD’s assets, namely ten local radio stations and the associated local 1 FM radio licences, interests in local multiplexes, and UKRD’s 50% interest in First Radio Sales (FRS) (the UKRD Acquisition).