Tom Baker: Taken out of Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005

The Oxford University Doctor Who Society Magazine TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee I ssue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 The Tides of Time 30 · 1 · Easter Vacation 2005 SHORELINES TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee By the Editor Issue 30 Easter Vacation 2005 Editor Matthew Kilburn The Road to Hell [email protected] I’ve been assuring people that this magazine was on its way for months now. My most-repeated claim has probably Bnmsdmsr been that this magazine would have been in your hands in Michaelmas, had my hard Wanderers 3 drive not failed in August. This is probably true. I had several days blocked out in The prologue and first part of Alex M. Cameron’s new August and September in which I eighth Doctor story expected to complete the magazine. However, thanks to the mysteries of the I’m a Doctor Who Celebrity, Get Me Out of guarantee process, I was unable to Here! 9 replace my computer until October, by James Davies and M. Khan exclusively preview the latest which time I had unexpectedly returned batch of reality shows to full-time work and was in the thick of the launch activities for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Another The Road Not Taken 11 hindrance was the endless rewriting of Daniel Saunders on the potentials in season 26 my paper for the forthcoming Doctor Who critical reader, developed from a paper I A Child of the Gods 17 gave at the conference Time And Relative Alex M. Cameron’s eighth Doctor remembers an episode Dissertations In Space at Manchester on 1 from his Lungbarrow childhood July last year. -

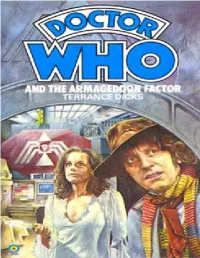

Terrance DICKS a Tribute

Terrance DICKS A tribute FEATURING: Chris achilleos John levene John peel Gary russell And many more Terrance DICKS A tribute CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF 2019 Contributors: Adrian Salmon, Gary Russell, John Peel, John Levene, Nick Walters, Terry Cooper, Adrian Sherlock, Rick Cross, Chris Achilleos, George Ivanoff, James Middleditch, Jonathan Macho, David A McIntee, Tim Gambrell, Wink Taylor. The right of contributing authors/artists to be identified as the Author/Owner of the Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Editor: Shaun Russell Editorial: Will Rees Cover by Paul Cowan Published by Candy Jar Books Mackintosh House 136 Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 1DJ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In Memory of Terrance Dicks 14th April 1935 – 29th August 2019 Adrian Salmon Gary Russell He was the first person I ever interviewed on stage at a convention. He was the first “famous” home phone number I was ever given. He was the first person to write to me when I became DWM editor to say congratulations. He was a friend, a fellow grumpy old git, we argued deliciously on a tour of Australian conventions on every panel about the Master/Missy thing. -

The Wall of Lies #174

The Wall of Lies Number 174 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA Final STATE Adelaide, September–October 2018 WEATHEr: Autumn Brought Him Free Leadership Vote Delays Who! by staff writers Selfish children spoil party games. The Liberal Party leadership spill of 24 August 2018 had an unfortunate consequence; preempting Doctor Who. Due to start at 4:10pm on Friday the 24th, The Magician's Apprentice was cancelled for rolling coverage of the three way party vote. The episode did repeat at 4.25am that day. Departing Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull frankly told us (The Wall of Lies 155, July 2015) that he had never watched Doctor Who. Incoming Prime Minister Scott Morrison thoughts on the show are not recorded. O The Wall of Lies lobbies successive u S t Communications Ministers to increase So on Regeneration: the 29th and 30th Prime resources and access for preserving the n! Ministers reunite for an absolutely dreadful nation’s television heritage. anniversary show. Free Tickets for Doctor Who Club! by staff writers BBC Worldwide and Sharmill Films come through again! On 20 August 2018 Sharmill Films said they had a deal with the BBC to present the as SFSA magazine # 33 yet unnamed series 11 premiere of Doctor Who in Australian cinemas. O u N t No ow Sharmill has presented the screenings of ! The Day of The Doctor (24 November 2013), Deep Breath (24 August 2014), The Power of the Daleks and The Return of Doctor Mysterio (12 November and 26 December 2016, respectively), The Pilot, Shada, and Twice Upon a Time (16 April, 24 November and 26 December 2017). -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

The Artwork Caught by the Tail*

The Artwork Caught by the Tail* GEORGE BAKER If it were married to logic, art would be living in incest, engulfing, swallowing its own tail. —Tristan Tzara, Manifeste Dada 1918 The only word that is not ephemeral is the word death. To death, to death, to death. The only thing that doesn’t die is money, it just leaves on trips. —Francis Picabia, Manifeste Cannibale Dada, 1920 Je m’appelle Dada He is staring at us, smiling, his face emerging like an exclamation point from the gap separating his first from his last name. “Francis Picabia,” he writes, and the letters are blunt and childish, projecting gaudily off the canvas with the stiff pride of an advertisement, or the incontinence of a finger painting. (The shriek of the commodity and the babble of the infant: Dada always heard these sounds as one and the same.) And so here is Picabia. He is staring at us, smiling, a face with- out a body, or rather, a face that has lost its body, a portrait of the artist under the knife. Decimated. Decapitated. But not quite acephalic, to use a Bataillean term: rather the reverse. Here we don’t have the body without a head, but heads without bodies, for there is more than one. Picabia may be the only face that meets our gaze, but there is also Metzinger, at the top and to the right. And there, just below * This essay was written in the fall of 1999 to serve as a catalog essay for the exhibition Worthless (Invaluable): The Concept of Value in Contemporary Art, curated by Carlos Basualdo at the Moderna Galerija Ljubljana, Slovenia. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 01/12/2012 A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra ABB V.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.1 ABB V.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.2 ABB V.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.3 ABB V.4 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Schmidt ABO Above the rim ACC Accepted ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam‟s Rib ADA Adaptation ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes‟ smarter brother, The AEO Aeon Flux AFF Affair to remember, An AFR African Queen, The AFT After the sunset AFT After the wedding AGU Aguirre : the wrath of God AIR Air Force One AIR Air I breathe, The AIR Airplane! AIR Airport : Terminal Pack [Original, 1975, 1977 & 1979] ALA Alamar ALE Alexander‟s ragtime band ALI Ali ALI Alice Adams ALI Alice in Wonderland ALI Alien ALI Alien vs. Predator ALI Alien resurrection ALI3 Alien 3 ALI Alive ALL All about Eve ALL All about Steve ALL series 1 All creatures great and small : complete series 1 ALL series 2 All creatures great and small : complete series 2 ALL series 3 All creatures great and small : complete series 3 *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ALL series 4 All creatures great -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Inside Outside in 2: an Outside in Extra!

INSIDE OUTSIDE IN 2: AN OUTSIDE IN EXTRA! Inside Outside In 2 as a compilation is ©2018 Robert Smith? All essays are ©2018 their respective authors. Outside In inside outside in 2 robert smith? (Originally published in the Nethersphere fanzine) Outside In Who The first two books cover Classic and New reviews, but with a twist. Well, technically a gimmickDoctor Who and storiesa twist. (including The gimmick Shada is). that, In the in second each volume, (recently there out is precisely one reviewer per story. So, in the first volume,Who there were 160 writers covering 160 Classic from ATB Publishing), that meant 125 writers Space/Timefor 125 New to Rainstories. Gods to How Time did Crash we toget Music to 125? of theWe Spherescounted. Notpretty to mentionmuch everything! all the televised So if it had stories a title of andcourse. a narrative, then it was included. Which meant everything from However, while a logistical triumph/headache/nightmareDoctor Who collection(delete asin appropriate), the gimmick is simply that: a way to anchor the collectionDoctor Who — making it, incidentally the most diverse professionally published existence — meaning that there are multiple styles. Much like itself, if you don’t like this week’s offering, somethingWho stories else will saying be along the shortly.same old things. So The twist though, is rather more delicious. The first volume was created as a hard.reaction Doctor to so Who many reviews of Classic the aim with that oneThe was Seeds to sayof Doom something different. Which, in a way, wasn’t that , like the weather, is endlessly discussable. -

Doctor Who: Armageddon Factor

DOCTOR WHO AND THE ARMAGEDDON FACTOR By TERRANCE DICKS Based on the BBC television serial by Bob Baker and Dave Martin by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation 1 The Vanishing Planet 'Atrios!' said the Doctor. 'Do you know, I've never been to Atrios.' Romana looked up from the TARDIS's control console. 'What about Zeos?' 'Where?' 'Zeos, its twin. "Atrios and Zeos are twin planets at the edge of the helical galaxy." Didn't they teach you anything at the Academy?' 'But we're not going to Zeos!' protested the Doctor. 'No, we're going to Atrios.' 'Well, what are we hanging about for? Why don't you get on with it?' Romana's hands moved skillfully over the controls. 'Atrios, here we come! I wonder what it's like?' The wandering Time Lord known as the Doctor and Romana his Time Lady companion, were nearing the end of a long and dangerous quest. Some time ago, the White Guardian, one of the most powerful beings in the cosmos had set them a vital task - to find and reassemble the six fragments of the Key to Time. Long ago the Key had been divided, and the segments scattered to the far corners of the cosmos. Now the Key was needed again, to enable the White Guardian to correct a state of temporal imbalance which was threatening the universe, and frustrate the schemes of the evil Black Guardian. The Doctor's task was complicated by the fact that the segments of the Key had a number of mysterious powers, including that of transmutation. -

A Thirteenth Doctorate

Number 43 Trinity 2019 A THIRTEENTH DOCTORATE Series Eleven reviewed Minor or major corrections, or referral? Virgin New Adventures • Meanings of the Mara The Time of the Doctor • Big Chief Studios • and more Number 43 Trinity 2019 [email protected] [email protected] oxforddoctorwho-tidesoftime.blog users.ox.ac.uk/~whosoc twitter.com/outidesoftime twitter.com/OxfordDoctorWho facebook.com/outidesoftime facebook.com/OxfordDoctorWho The Wheel of Fortune We’re back again for a new issue of Tides! After all this time anticipating her arrival true, Jodie Whittaker’s first series as the Doctor has been and gone, so we’re dedicating a lot of coverage this issue to it. We’ve got everything from reviews of the series by new president Victoria Walker, to predictions from society stalwart Ian Bayley, ratings from Francis Stojsavljevic, and even some poetry from Will Shaw. But we’re not just looking at Series Eleven. We’re looking back too, with debates on the merits of the Capaldi era, a spirited defence of The Time of the Doctor, and drifting back through the years, even a look at the Virgin New Adventures! Behind the scenes, there’s plenty of “change, my dear, and not a moment too soon!” We bid adieu to valued comrades like Peter, Francis and Alfred as new faces are welcomed onto the committee, with Victoria now helming the good ship WhoSoc, supported by new members Rory, Dahria and Ben, while familiar faces look on wistfully from the port bow. It’s also the Society’s Thirtieth Anniversary this year, which will be marked by a party in Mansfield College followed by a slap-up dinner; an event which promises to make even the most pampered Time Lord balk at its extravagance! On a personal note, it’s my last year before I graduate Oxford, at least for now, so when the next issue is out, I’ll be writing from an entirely new place. -

Fans' List-Making: Memory, Influence, and Argument in the “Event” of Fandom

85 Fans’ list-making: memory, influence, and argument in the “event” of fandom A produção de listas de fãs: memória, influência e debate no “evento” do fandom PAUL BOOTH* DePaul University. Chicago –, IL, United States of America ABSTRACT * Associate Professor, To date, there have been very few studies on fandom and fan audiences that have focused Media and Cinema on practice of fans’ list-making. This article, which introduces this topic for analysis, first Studies, College of Communication, DePaul argues that fans’ list-making presents fans with an opportunity to simultaneously memo- University. E-mail: rialize, influence, and argue. Second, this article offers list-making as a tool for observing [email protected] commonalities between the different practices of media, music, and sports fans. Finally, this article cautions against the universality of these list-making practices, illustrating how list-making shows the artificiality of the event in fan activities. Using a combination of Žižekian and Couldryian analyses, this article argues that fans’ list-making becomes a new way of reading fandom reductively, and highlights the media ritual of fandom. Keywords: Fandom, fan studies, memory, influence, hierarchy, list RESUMO Até o momento, há poucos estudos de fandom e de audiência dos fãs que enfoquem a práti- ca da elaboração de listas por eles. Este artigo, que introduz a análise do tema, inicialmente defende que a feitura de listas por fãs permite que eles tenham uma oportunidade de, ao mesmo tempo, recordar, influenciar e discutir. Em segundo lugar, o artigo mostra a elabo- ração de listas como um instrumento para perceber semelhanças entre as diferentes prá- ticas dos fãs de mídia, música e esportes. -

Orthia & Morgain 2016 the Gendered Culture of Scientific Competence

CULTURE OF SCIENTIFIC COMPETENCE 1 The Gendered Culture of Scientific Competence: A Study of Scientist Characters in Doctor Who 1963-2013 Lindy A. Orthia and Rachel Morgain The Australian National University Author Note Lindy A. Orthia, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, The Australian National University; Rachel Morgain, School of Culture, History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University. Thanks to Emlyn Williams for statistical advice, and two anonymous peer reviewers for their useful suggestions. Address correspondence concerning this manuscript to Lindy A. Orthia, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, The Australian National University, Peter Baume Building 42A, Acton ACT 2601, Australia. Email: [email protected] Published in Sex Roles. Final publication available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0597-y CULTURE OF SCIENTIFIC COMPETENCE 2 Abstract The present study examines the relationship between gender and scientific competence in fictional representations of scientists in the British science fiction television program Doctor Who. Previous studies of fictional scientists have argued that women are often depicted as less scientifically capable than men, but these have largely taken a simple demographic approach or focused exclusively on female scientist characters. By examining both male and female scientists (n = 222) depicted over the first 50 years of Doctor Who, our study shows that, although male scientists significantly outnumbered female scientists in all but the most recent decade, both genders have consistently been depicted as equally competent in scientific matters. However, an in-depth analysis of several characters depicted as extremely scientifically non-credible found that their behavior, appearance, and relations were universally marked by more subtle violations of gender expectations.