Fans' List-Making: Memory, Influence, and Argument in the “Event” of Fandom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample File Under Licence

THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK B CREDITS LINE DEVELOPER: Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan WRITING: Darren Pearce and Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Nathaniel Torson EDITING: Dominic McDowall-Thomas COVER: Paul Bourne GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Paul Bourne CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Dominic McDowall-Thomas ART DIRECTOR: Jon Hodgson SPECIAL THANKS: Georgie Britton and the BBC Team for all their help. “My First Begins With An Unearthly Child” The First Doctor Sourcebook is published by Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd (UK reg. no.6036414). Find out more about us and our games at www.cubicle7.co.uk © Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd. 2013 BBC, DOCTOR WHO (word marks, logos and devices), TARDIS, DALEKS, CYBERMAN and K-9 (wordmarks and devices) are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used Sample file under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. Doctor Who logo © BBC 2009. TARDIS image © BBC 1963. Dalek image © BBC/Terry Nation 1963.Cyberman image © BBC/Kit Pedler/Gerry Davis 1966. K-9 image © BBC/Bob Baker/Dave Martin 1977. Printed in the USA THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK THE FIRST DOCTOR SOURCEBOOK B CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE 4 CHAPTER SEVEN 89 Introduction 5 The Chase 90 Playing in the First Doctor Era 6 The Time Meddler 96 The Tardis 12 Galaxy Four 100 CHAPER TWO 14 CHAPTER EIGHT 104 An Unearthly Child 15 The Myth Makers 105 The Daleks 20 The Dalek’s Master Plan 109 The Edge of Destruction 26 The Massacre 121 CHAPTER THREE 28 CHAPTER NINE 123 Marco Polo 29 The Ark 124 The Keys of Marinus 35 The Celestial Toymaker 128 The -

The Artwork Caught by the Tail*

The Artwork Caught by the Tail* GEORGE BAKER If it were married to logic, art would be living in incest, engulfing, swallowing its own tail. —Tristan Tzara, Manifeste Dada 1918 The only word that is not ephemeral is the word death. To death, to death, to death. The only thing that doesn’t die is money, it just leaves on trips. —Francis Picabia, Manifeste Cannibale Dada, 1920 Je m’appelle Dada He is staring at us, smiling, his face emerging like an exclamation point from the gap separating his first from his last name. “Francis Picabia,” he writes, and the letters are blunt and childish, projecting gaudily off the canvas with the stiff pride of an advertisement, or the incontinence of a finger painting. (The shriek of the commodity and the babble of the infant: Dada always heard these sounds as one and the same.) And so here is Picabia. He is staring at us, smiling, a face with- out a body, or rather, a face that has lost its body, a portrait of the artist under the knife. Decimated. Decapitated. But not quite acephalic, to use a Bataillean term: rather the reverse. Here we don’t have the body without a head, but heads without bodies, for there is more than one. Picabia may be the only face that meets our gaze, but there is also Metzinger, at the top and to the right. And there, just below * This essay was written in the fall of 1999 to serve as a catalog essay for the exhibition Worthless (Invaluable): The Concept of Value in Contemporary Art, curated by Carlos Basualdo at the Moderna Galerija Ljubljana, Slovenia. -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled. -

Gallifrey: No

GALLIFREY: NO. 5 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Peaty,Una McCormack,David Llewellyn,Gary Russell,Sean Carlsen,Louise Jameson,Lalla Ward | none | 28 Feb 2013 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844359585 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Gallifrey: No. 5 PDF Book As if she's fallen off a cliff. Arcadia , Gallifrey's "second city", was protected by a large number of sky trenches. Series 8. The War Doctor was present at the Fall of Arcadia , and it was there that he left his warning of "No More" for the combatants. Gallifrey had at least two large moons and a ring system, similar to Saturn in Earth 's solar system. Episode 3. What is Doctor Who? What did the Master do? TV : The Invasion of Time Rassilon later referred to the area that the barn in which the Doctor had slept as a child as the Drylands , claiming that no one of importance lived there. There's some sloppy exposition, revealing that The Fourth Doctor got stuck between times during his abduction and he has to sit this one out and some other sundries. The Tenth Doctor returned it to the time lock by shooting and destroying the diamond which connected Gallifrey to Earth. Share Tweet. Missy later told the Doctor that Gallifrey had returned to its original position. It was also called Gallifrey Original. I won't look. Wait, wait, wait, wait. Although these battles were stopped by Rassilon, the Death Zone remained and later became home to the Tomb of Rassilon. Doctor Who : Gallifrey stories. Basically The Third Doctor and Sarah Jane are traversing the Mountain to get to the Tomb when they come upon this guy, and there's nothing about him that doesn't suck. -

The Wall of Lies #141

The Wall of Lies Number 141 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA MFinal FINAL Adelaide, March--April 2013 WEATHER: Hot for some Free Daleks spotted in London by staff writers An Adventure in Space and Time: end of days or win? A February 17 fashion shoot featuring the effervescent Mark Gatiss modelling cold weather gear on Westminster Bridge was photo-bombed by Daleks. “Do you speak English, dearie?,” “Are you looking for the tourist bureau?” and “Are you local?” were some of the things the wandering aliens were asked by the crowd. Eventually they departed in a flying saucer which closely resembled two pie dishes, but not before exterminating the one who called them “dearie”. And quite right too. A spokesperson for the Eurosceptic UK Independence O Party said there were no exceptions to their anti-immi- ut t N grant policy for aliens, terrestrial or extra-terrestrial. No ow A horribleness monster with an We asked for another quote, but they appeared to ! evil plan and (left) a dalek. have been a bit exterminated. Doctor Who Showcased by staff writers BBC names Doctor Who as star product. A celebration of Doctor Who’s 50th anniversary was the big event Chameleon Factor # 80 at the television sales fair known as the British Broadcasting Corporation Worldwide Showcase 2013. This ran from 24 to 27 O u February in Liverpool. BBC Worldwide claims sales for the pro- S t So gram into over over 200 countries and territories. -

2016 Topps Doctor Who Extraterrestrial

Base Cards 1 The First Doctor 34 Judoon 67 Dragonfire 2 The Second Doctor 35 The Family of Blood 68 Silver Nemesis 3 The Third Doctor 36 The Adipose 69 Ghost Light 4 The Fourth Doctor 37 Vashta 70 The End of the World 5 The Fifth Doctor 38 Tritovores 71 Aliens of London 6 The Sixth Doctor 39 Prisoner Zero 72 Dalek 7 The Seventh Doctor 40 The Tenza 73 The Parting of the Ways 8 The Eighth Doctor 41 The Silence 74 School Reunion 9 The War Doctor 42 The Wooden King 75 The Impossible Planet 10 The Ninth Doctor 43 The Great Intelligence 76 "42" 11 The Tenth Doctor 44 Ice Warrior Skaldak 77 Utopia 12 The Eleventh Doctor 45 Strax 78 Planet of the Ood 13 The Twelfth Doctor 46 Slitheen 79 The Sontaran Stratagem 14 Susan 47 Zygons 80 The Doctor's Daughter 15 Zoe 48 Sycorax 81 Midnight 16 Sarah Jane 49 The Master 82 Journey's End 17 Ace 50 Missy 83 The Waters of Mars 18 Rose 51 The Daleks 84 Victory of the Daleks 19 Captain Jack 52 The Sensorites 85 The Pandorica Opens 20 Martha 53 The Dalek Invasion of Earth 86 Closing Time 21 Donna 54 Tomb of the Cybermen 87 A Town Called Mercy 22 Amy 55 The Invasion 88 The Power of Three 23 Rory 56 The Claws of Axos 89 The Rings of Akhaten 24 Clara 57 Frontier in Space 90 The Night of the Doctor 25 Osgood 58 The Time Warrior 91 The Time of the Doctor 26 River 59 Death to the Daleks 92 Into the Dalek 27 Davros 60 Pyramids of Mars 93 Time Heist 28 Rassilon 61 The Keeper of Traken 94 In the Forest of the Night 29 The Ood 62 The Five Doctors 95 Before the Flood 30 The Weeping Angels 63 Resurrection of the Daleks 96 -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date

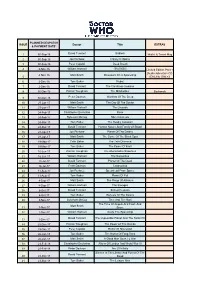

PLANNED DESPATCH ISSUE Doctor Title EXTRAS & PAYMENT DATE* 1 30-Sep-16 David Tennant Gridlock Wallet & Travel Mug 2 30-Sep-16 Jon Pertwee Colony In Space 3 30-Sep-16 Peter Capaldi Deep Breath 4 4-Nov-16 William Hartnell 100,000BC Limited Edition Print + [Audio Adventure CD 4-Nov-16 Matt Smith Dinosaurs On A Spaceship 5 (ONLINE ONLY)] 6 2-Dec-16 Tom Baker Robot 7 2-Dec-16 David Tennant The Christmas Invasion 8 30-Dec-16 Patrick Troughton The Mindrobber Bookends 9 30-Dec-16 Peter Davison Warriors Of The Deep 10 27-Jan-17 Matt Smith The Day Of The Doctor 11 27-Jan-17 William Hartnell The Crusade 12 24-Feb-17 Christopher Eccleston Rose 13 24-Feb-17 Sylvester McCoy Silver Nemesis 14 24-Mar-17 Tom Baker The Deadly Assassin 15 24-Mar-17 David Tennant Human Nature And Family Of Blood 16 21-Apr-17 Jon Pertwee Planet Of The Daleks 17 21-Apr-17 Matt Smith The Curse Of The Black Spot 18 19-May-17 Colin Baker The Twin Dilemma 19 19-May-17 Tom Baker The Power Of Kroll 20 16-Jun-17 Patrick Troughton The Abominable Snowmen 21 16-Jun-17 William Hartnell The Sensorites 22 14-Jul-17 David Tennant Planet Of The Dead 23 14-Jul-17 Peter Davison Castrovalva 24 11-Aug-17 Jon Pertwee Spearhead From Space 25 11-Aug-17 Tom Baker Planet Of Evil 26 8-Sep-17 Matt Smith The Rings Of Akhaten 27 8-Sep-17 William Hartnell The Savages 28 6-Oct-17 David Tennant School Reunion 29 6-Oct-17 Tom Baker Genesis Of The Daleks 30 3-Nov-17 Sylvester McCoy Time And The Rani The Time Of Angels And Flesh And Matt Smith 31 3-Nov-17 Stone 32 1-Dec-17 William Hartnell Inside The Spaceship -

''Doctor Who'' - the First Doctor Episode Guide Contents

''Doctor Who'' - The First Doctor Episode Guide Contents 1 Season 1 1 1.1 An Unearthly Child .......................................... 1 1.1.1 Plot .............................................. 1 1.1.2 Production .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Themes and analyses ..................................... 4 1.1.4 Broadcast and reception .................................... 4 1.1.5 Commercial releases ..................................... 4 1.1.6 References and notes ..................................... 5 1.1.7 Bibliography ......................................... 6 1.1.8 External links ......................................... 6 1.2 The Daleks .............................................. 7 1.2.1 Plot .............................................. 7 1.2.2 Production .......................................... 8 1.2.3 Themes and analysis ..................................... 8 1.2.4 Broadcast and reception .................................... 8 1.2.5 Commercial releases ..................................... 9 1.2.6 Film version .......................................... 10 1.2.7 References .......................................... 10 1.2.8 Bibliography ......................................... 10 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 11 1.3 The Edge of Destruction ....................................... 11 1.3.1 Plot .............................................. 11 1.3.2 Production .......................................... 11 1.3.3 Broadcast and reception ................................... -

Doctor Who Classic Touches Down on Boxing Day

DOCTOR WHO CLASSIC TOUCHES DOWN ON BOXING DAY London, 20 December 2019: BritBox Becomes Home to Doctor Who Classic on 26th December Doctor Who fans across the land get ready to clear their schedules as the biggest Doctor Who Classic collection ever streamed in the UK launches on BritBox from Boxing Day. From 26th December, 627 pieces of Doctor Who Classic content will be available on the service. This tally is comprised of a mix of episodes, spin-offs, documentaries, telesnaps and more and includes many rarely-seen treasures. Subscribers will be able to access this content via web, mobile, tablet, connected TVs and Chromecast. 129 complete stories, which totals 558 episodes spanning the first eight Doctors from William Hartnell to Paul McGann, form the backbone of the collection. The collection also includes four complete stories; The Tenth Planet, The Moonbase, The Ice Warriors and The Invasion, which feature a combination of original content and animation and total 22 episodes. An unaired story entitled Shada which was originally presented as six episodes (but has been uploaded as a 130 minute special), brings this total to 28. A further two complete, solely animated stories - The Power Of The Daleks and The Macra Terror (presented in HD) - add 10 episodes. Five orphaned episodes - The Crusade (2 parts), Galaxy 4, The Space Pirates and The Celestial Toymaker - bring the total up to 600. Doctor Who: The Movie, An Unearthly Child: The Pilot Episode and An Adventure In Space And Time will also be available on the service, in addition to The Underwater Menace, The Wheel In Space and The Web Of Fear which have been completed via telesnaps. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

Gallifrey: No. 5 Free

FREE GALLIFREY: NO. 5 PDF James Peaty,Una McCormack,David Llewellyn,Gary Russell,Sean Carlsen,Louise Jameson,Lalla Ward | none | 28 Feb 2013 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844359585 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Classical Gallifrey: Serial The Five Doctors It is the original home world of the Time Lordsthe civilisation to which the main protagonist, the Doctor belongs. It is located in a binary star system [2] million light years from Earth. In the revived series onwards Gallifrey was originally referred to as having been destroyed in the Time Warwhich was fought between the Time Lords and the Daleks. It was depicted in a flashback in " The Sound of Drums " [1] and appeared prominently in " The End of Time " — It is never definitively stated when the appearances of Gallifrey take place. As the planet is often reached by means of time travel, its relative present could conceivably exist almost anywhere in the Earth 's past or future as well as anywhere in the conceivable universe. From space, Gallifrey is seen as a yellow-orange planet and was close enough to central space lanes for spacecraft to require clearance from Gallifreyan Space Traffic Control as they pass through Gallifrey: No. 5 system. The Time Lords' principal city, named The Capitol, consists of shining towers protected by a mighty glass dome. The planet's so-called "second city" is Arcadia, and is seen falling to the Daleks in the minisode " The Last Day. The Doctor's granddaughter Susan first describes her home world not named as "Gallifrey" at the time as having bright, silver-leafed trees and a burnt orange sky at night in the serial The Sensorites In The Time Monsterthe Third Doctor says that "When I was a Gallifrey: No.