Chris Badgley Interviewer: Leif Fredrickson Date of Interview: November 21, 2019 Project: Missoula Music History Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grouplove/51765840/1?Loc=Interstitialskip

December 9, 2011 http://www.usatoday.com/life/music/ontheverge/story/2011-12-06/on-the-verge-with-indie-rock-group-grouplove/51765840/1?loc=interstitialskip Grouplove grew out of friendship By Korina Lopez, USA TODAY Group love, indeed: This Los Angeles-based quintet certainly lives up to its name. "We never planned to be a band. We were friends first and we just love being together," says lead singer Christian Zucconi. "Grouplove grew organically from that love." Their debut album, with the tongue-in-cheek title Never Trust a Happy Song, is quickly spreading the love, too. Their sweet and savory mix of jangly, upbeat melodies, Zucconi's anguished howl and keyboardist Hannah Hooper's coquettish backup vocals have been making the rounds in indie rock circles and on the charts. Joyful, noisy single Colours peaked at No. 12 on USA TODAY's alternative chart. Another track, Tongue Tied, lassoed the new iPod Touch commercial, which ran during the Grammy nominations concert and has continued since Thanksgiving. Add Grouplove's lock as the opening band for Young the Giant's tour in March and April, and it's no wonder they're so lovey-dovey. Happy accidents: Zucconi wasn't always this upbeat. "Before Grouplove, I was in other bands, but the timing never seemed right," he says. "I'd wake up every day depressed, I spent so many years miserable doing music. But it's wonderful now how we overcame everything together. It's funny that Grouplove is such a happy band." The band members met each other in 2008 at an artist commune in Crete. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Perth Music Interviews Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Amber Flynn

Perth Music Interviews Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Amber Flynn (Rabbit Island) Sean O’Neill (Hang on Saint Christopher) Bill Darby David Craddock (Davey Craddock and the Spectacles) Scott Tomlinson (Kill Teen Angst) Thomas Mathieson (Mathas) Joe Bludge (The Painkillers) Tracey Read (The Wine Dark Sea) Rob Schifferli (The Leap Year) Chris Cobilis Andy Blaikie by Benedict Moleta December 2011 This collection of interviews was put together over the course of 2011. Some of these people have been involved in music for ten years or more, others not so long. The idea was to discuss background and development, as well as current and long-term musical projects. Benedict Moleta [email protected] Ben Stewart (Filmmaker) Were you born in Perth ? Yeah, I was born in Mt Lawley. You've been working on a music documentary for a while now, what's it about ? I started shooting footage mid 2008. I'm making a feature documentary about a bunch of bands over a period of time, it's an unscientific longitudinal study of sorts. It's a long process because I want to make an observational documentary with the narrative structure of a fiction film. I'm trying to capture a coming of age cliché but character arcs take a lot longer in real life. I remember reading once that rites of passage are good things to structure narratives around, so that's what I'm going to do, who am I to argue with a text book? Fair call. I guess one of the characteristics of bands developing or "coming of age" is that things can emerge, change, pass away and be reconfigured quickly. -

90115ThAvenue•SouthMilwaukee,WI53172 414.766.5049•

th 901 15 Avenue • South Milwaukee, WI 53172 414.766.5049 • www.southmilwaukeepac.org For Immediate Release Contact: Michelle Majerus-Uelmen September 5, 2017 Marketing Director 414-766-5049 ACG PRESENTS VIOLENT FEMMES ANNOUNCE VIVA WISCONSIN 2017 TOUR AT SOUTH MILWAUKEE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER FRIDAY, OCTOBER 20, 7:30 PM (South Milwaukee, WI) – It has been 19 years since the Violent Femmes did a special tour of small theatres around Wisconsin. That tour resulted in the live CD, ”Viva Wisconsin”. This fall they will visit 5 cities again playing small, intimate theatres. All shows go on sale Friday September 8. Peter Jest will again be the promoter for this tour. “I am very excited and proud to be promoting these dates. I have been promoting 34 years and it is an honor to bring Wisconsin’s most famous and internationally known band back to their home state to play. The Milwaukee band that was “discovered” outside a Milwaukee Theatre by the Pretenders now will go inside 5 Wisconsin theaters -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Some Advice for Phone-Addicted Youth Who Want To

The Roots Report: Look What’s Going Down: Artists have a duty to voice their opinions Okee dokee folks… “It’s s time we stop, hey, what’s that sound, everybody look what’s going down.” This is from one of the most famous protest songs ever written, “For What It’s Worth,” by Stephen Stills (Buffalo Springfield). It was written more than 50 years ago in response to the Sunset Strip curfew riots in California and is still revered as one of the best songs of that generation. A few years later, Neil Young wrote his song “Ohio” about the Kent State shootings. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young quickly recorded this song, and when it was released as a single, it was backed with another Stephen Stills protest anthem “Find The Cost Freedom.” At the time, “Ohio” was banned by some radio stations, but today it is one of the few actual protest songs still being played on radio. These songs, the bands and the writers were major inspirations and influences for me as a musician and songwriter. Not only do I perform “Ohio” with my band Forever Young and “For What It’s Worth” when I play solo, but I have written many sociopolitical songs of my own that are part of my body of solo work. I feel protest songs need to be written, but they are the hardest type of song to get right. They need to express the concern and anger of the subject matter and marry it perfectly with a melody to make the song viable. -

Kapuzine März/April 2004

IMPRESSUM ::: KAPUZINE SEPT – OKT 2004 REDAKTION / MITARBEITER DIESER AUSGABE Anatol Bogendorfer, Philip Huemer, Pezzy Burri- to, Huckleberry Renner, Bert Estl, Herta Gurtner, Gerlinde Schmierer, Georg Gartlgruber, Christine Hofer, Christian Wellmann LAYOUT Judith Holzer, Agnes Steiner MEDIENINHABER, HERAUSGEBER KV KAPU, Kapuzinerstr. 36, 4020 Linz Tel ::: 070/779660 e-mail ::: [email protected] HERSTELLUNG D e n k m a y r, 4020 Linz R e s l w e g 3 Neben der Ankündigung der Vereinsaktivitäten sieht sich das KAPUZINE als medialer Freiraum, der die Verbreitung 01 „anderer Nachrichten“ ermöglicht. Liebe Kapu-Besucher! Liebe Einwohner dieser Stadt! Soll´s uns an den Kragen gehen? Wir wis- ta, Strahler 80, Valina, Soundsgood, um sen es noch nicht. einige zu nennen. Die Kapu durchläuft derzeit eine finanziel- le Krise, nicht die erste in der Geschichte, Seit Beginn an war dieses Wesen definiert denn zu kämpfen hatten wir seit jeher. durch eine offene Struktur und den Do It Nun stehen wir allerdings vor einer Hür- Yourself-Gedanken, der dazu auffordert, de, von deren Bewältigung die Zukunft der selbst tätig zu werden und nicht bloß zu Kapu abhängen kann und welche durchaus konsumieren. parteipolitisch, jedenfalls aber gesell- Noch immer treffen sich jeden Mittwoch schaftspolitisch zu interpretieren ist. um 19 Uhr Menschen in der Kapu um so- Es ist Zeit, euch zu informieren, Stand- wohl Programm und Vereinsangelegenhei- punkte klarzumachen, gemeinsam zu re- ten zu diskutieren, als auch um wichtige flektieren..... organisatorische Aufgaben einzuteilen, die oftmals im Hintergrund passieren und auch Die Kapu ist ein unabhängiger Kulturverein vom Publikum schwer zu erkennen sind, und existiert seit 1985. -

Adams Avenue Street Fair

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, Tfolk, gospel, and bluegrass music news September-October 2004 THIRD ANNIVERSARY ISSUE Vol. 4, No. 1 official program adams ave. street fair - what to see , where to 7 S t a g e s • 8 0 M u s i c a l A c t s • go , how to get there • O s v Welcome ………………3 e h Street Fair Headliners …8 r t Performing Artists …10-19 o 4 o Schedules, Map ………12 0 B 0 s F P t Welcome Mat ………3 o f Mission Statement o a Contributors d r , C Full Circle.. …………4 A r San Diego Music Awards & Lou Curtiss t s s s t e Front Porch …………6 Stag & CeeCee James r 7 A Victoria Robertson C , Acoustic Music San Diego r d a Adams Ave. Street Fair o f o See pp. 8-19 t F Of Note. ……………19 s 0 Victoria Robertson B 0 Joe Morgan o 4 Northstar Session o t r Ramblin’... …………20 h e s Bluegrass Corner v Zen of Recording O José Sinatra Jim McInnes’ Radio Daze Funk • Country • World • Blues • Jazz • Folk • Zydeco • Rockabilly • Latin ‘Round About ....... …22 Sept.-Oct. Music Calendar The Local Seen ……23 nce again, the last weekend in September brings and many more — and continues to draw musicians to San Diego from all over the country who seek fame and exposure. Photo Page us the the largest, most diverse, free music festival Othat may exist in the world today. At the Adams Fun and family-oriented, there is so much to enjoy at the Avenue Street Fair, located between Bancroft Street and 35th Adams Avenue Street Fair: Three beer gardens, carnival rides, Street in Normal Heights, more than 80 different musical acts a pancake breakfast, and more than 400 food and arts and will take the stage over a two-day period: Saturday, September crafts booths. -

Metro Song List

Metro Song List Song Title Artist All About Tonight Blake Sheldon All Summer Long Kid Rock Animal Neon trees Anyway Martina Mc Bride At Last Etta James Backwoods Justin Moore Bad Romance Lady Ga Ga Beer On The Table Josh Thompson Boots On Randy Houser Born This Way Lady Ga Ga Brick House Commodores Break Your Heart Taio Cruz California Girls Katy Perry Copperhead Road Steve Earl Country Girl Shake It For Me Luke Bryan Cowboy Casanova Carrie Underwood Crazy Bitch Buck Cherry Crazy Women LeeAnn Rimes Don't Wanna Go Home Jason Derulo Dirty Dancer Enrique Iglesias DJ Got Us Falling In Love Usher/ Pitbull Domino Jessie J Don't Stop Believin' Journey Drink In My Hand Eric Church Drunker Than Me Trent Tomlinson Dynamite Taio Cruz Evacuate the Dance Floor Cascada Faithfully Journey Firework Katy Perry Forget You Cee Lo Green Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd Get This Party Started Pink Give Me Everything Tonight Pit Bull feat. Ne-Yo God Bless The USA Lee Greenwood Gunpowder And Lead Maranda Lambert Hard to Handle The Black Crowes Hate Myself For Loving You Joan Jett Hella Good No Doutb Here For The Party Gretchen Wilson Hill Billy Shoes Montgomery Gentry Hill Billy Rap Neil Mc Coy Home Sweet Home The Farm Honky Tonk Ba Donk A Donk Trace Adkins Honky Tonk Stomp Brooks and Dunn Hurts So Good John Cougar Mellencamp I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas I Got Your Country Right Here Gretchen Wilson I Hate Myself For Loving You Joan Jett I Like It Enrique Iglesias In My Head Jason Derulo I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett I Need You Now Lady Antebellum I won't give up Jason Mraz It Happens Sugarland Jenny (867-5309) Tommy Tutone Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield Just A Kiss Lady Antebellum Just Dance Lady Ga Ga Kerosene Miranda Lambert Last Friday Night (TGIF) Katy Perry Looking For A Good Time Lady Antebellum Love Don't Live Here Lady Antebellum Love Shack B 52's Mony Mony Billy Idol Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Mr. -

Vf & Tso Mofo Mr

VIOLENT FEMMES AND THE TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA World Premiere Monday 22 & Tuesday 23 January Due to popular demand Mona Foma today announced an extra show for the world premiere of the Violent Femmes performing with the TSO. For two nights only, the Violent Femmes will take their acoustic punk-rock and work with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra to reimagine it as a full orchestra experience. Conducted by Hamish McKeich they’ll perform a long list of cult classics such as Add It Up, Blister In The Sun, Kiss Off, Gone Daddy Gone, American Song and Gimme The Car at The Federation Concert Hall on Monday 22 and Tuesday 23 January. “Most rock bands would blow off an orchestra with the amplifiers, but for these two shows we’re prepared to back off on the volume and actually play almost at the same volume as the orchestra musicians and create a more unified approach, “ said Brian Ritchie. The Violent Femmes were formed in 1981 as an acoustic band playing on the streets of Milwaukee. Their main influences at that time were Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps and The Velvet Underground. Enduring a couple of hiatuses throughout their 36-plus year career, the band — original members Gordon Gano and Brian Ritchie, along with drummer John Sparrow have been performing steadily since reuniting again in 2013. The TSO’s performance with the Violent Femmes represents another innovative collaboration for the orchestra, which in 2017 alone has seen sold out concerts with vocal star Kate Miller-Heidke, a Dark MOFO collaboration with Norwegian metal band Ulver, an original show with comedy trio Tripod and a sold out concert with ARIA award-winning and multi-platinum artist Megan Washington. -

December 2020 New Releases

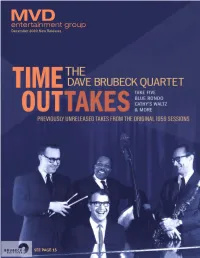

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR. -

Interview by Aphid Peewit

nyone who’s had the good fortune of experiencing the Supersuckers Hell, any one of those would be enough for me to grin like an Alive, knows that frontman Eddie Spaghetti wears a black cowboy hat, idiot for years to come. But the more I think about it, the more I think Mr. Marlboro Man sunglasses and rockabilly sideburns. But the thing that Spaghetti’s shit-eating grin might be due to his own realization that he and sticks in your mind’s eye long after his bandmates are pulling off the the last power chord fades away is nearly impossible: they are living the that damn shit-eating grin that refus- overblown decadent cartoon lifestyle es to leave his face. He looks like the of big-time arena-rock rockstars AND alley cat that just ate a cage-full of they’re keeping their punk rock canaries. “cred.” But what the fuck is he And just how the hell do they do smirking about? it? It’s a good ol’ go-fuck-yourself atti- Is it the natural confidence tude connected to that same shit-eat- of someone who knows his order was ing grin that lets everyone know that “super-sized” when they were hand- the Supersuckers’ tongues are firmly ing out charisma? Or is it the swagger in cheek. of someone who’s recently flipped off However you choose to dissect it, the major label suckwads and started underneath it all Eddie Spaghetti’s his own record label and can now do INTERVIEW BY shit-eating grin simply means this: this pretty much whatever he damn well APHID PEEWIT fucker’s just having too damn much pleases? Or could it be the natural fun.