The Settling of Quaker Communities in Seventeenth-Century Wiltshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the Differences Between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the differences between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas This document should be read in conjunction with the School Places Strategy 2017 – 2022 and provides an explanation of the differences between the Wiltshire Community Areas served by the Area Boards and the School Planning Areas. The Strategy is primarily a school place planning tool which, by necessity, is written from the perspective of the School Planning Areas. A School Planning Area (SPA) is defined as the area(s) served by a Secondary School and therefore includes all primary schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into that secondary school. As these areas can differ from the community areas, this addendum is a reference tool to aid interested parties from the Community Area/Area Board to define which SPA includes the schools covered by their Community Area. It is therefore written from the Community Area standpoint. Amesbury The Amesbury Community Area and Area Board covers Amesbury town and surrounding parishes of Tilshead, Orcheston, Shrewton, Figheldean, Netheravon, Enford, Durrington (including Larkhill), Milston, Bulford, Cholderton, Wilsford & Lake, The Woodfords and Great Durnford. It encompasses the secondary schools The Stonehenge School in Amesbury and Avon Valley College in Durrington and includes primary schools which feed into secondary provision in the Community Areas of Durrington, Lavington and Salisbury. However, the School Planning Area (SPA) is based on the area(s) served by the Secondary Schools and covers schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into either The Stonehenge School in Amesbury or Avon Valley College in Durrington. -

William Historian of Malmesbury, of Crusade

William of Malmesbury, Historian of Crusade Rod Thomson University of Tasmania William of Malmesbury (c.1096 - c.1143), well known as one of the greatest historians of England, is not usually thought of as a historian of crusadingl His most famous work, the Gesta Regum Anglorum, in five books subdivided into 449 chapters, covers the history of England from the departure of the Romans until the early 1120s.2 But there are many digressions, most of them into Continental history; William is conscious of them and justifies them in explicit appeals to the reader. 3 Some provide necessary background to the course of English affairs, some are there for their entertainment value, and some because of their intrinsic importance. William's account of the First Crusade comes into the third category. It is the longest of all the diversions, occupying the last 46 of the 84 chapters which make up Book IV, or about 12% of the complete Gesta Regum. This is as long as a number of independent crusading chronicles (such as Fulcher's Gesta Francorum Iherosolimitanum Peregrinantium in its earliest edition, or the anonymous Gesta Francorum) and the story is brilliantly told. It follows the course of the Crusade from the Council of Clermont to the capture of Jerusalem, continuing with the so-called Crusade of H aI, and the deeds of the kings of Jerusalem and other great magnates such as Godfrey of Lorraine, Bohemond of Antioch, Raymond of Toulouse and Robert Curthose. The detailed narrative concludes in 1102; some scattered notices come down to c.1124, close to the writing of the Gesta, with a very little updating carried out in H34-5. -

Westbury Station I Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local Area Map

Westbury Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map km 0 0.5 0 Miles 0.25 Key FC Westbury United Football Club 1 L Westbury Library 0 m in ut LS Local Shops es w Station a S Westbury Swimming Pool lk A in g W d Westbury Lake is ta Westbury Wilts Youth n WW c e Sailing Association Footpaths B C Station WW W FC e e c c n Key n a a t t s s i i d d g g n Bus Stop n i A i Town Centre k k l l a a w w s Rail replacement Bus Stop s e e t t u u n n i i L m m 0 0 1 Station Entrance/Exit 1 LS Taxi Rank S Rail replacement services from the bus stop adjacent to the ticket office. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at August 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Bath ^ D1 B Limpley Stoke D1 B West Lavington 87 A Boreham D1 C Market Lavington 87 A West Wilts Industrial Estate D1 B Bradford-on-Avon ^ D1 B Potterne 87 A Wilton D1* C Bratton 87 A Salisbury ^ D1* C Winsley D1 B Claverton D1 B South Newton D1* C Yarnbrook D1, 87 B Codford St Mary (& St D1* C Steeple Langford D1* C Peter) Devizes 87 A Trowbridge ^ D1, 87 B Edington 87 A Upton Lovell D1* C Erlestoke 87 A Upton Scudamore D1 C Great Cheverell 87 A Warminster ^ D1 C 15 minutes walk from this B Hawkeridge D1 station (see local area Notes map) Heytesbury D1* C Westbury (Town Centre) 87 A Bus route D1 operates daily. -

Draft Topic Paper 5: Natural Environment/Biodiversity

Wiltshire Local Development Framework Working towards a Core Strategy for Wiltshire Draft topic paper 5: Natural environment/biodiversity Wiltshire Core Strategy Consultation June 2011 Wiltshire Council Information about Wiltshire Council services can be made available on request in other languages including BSL and formats such as large print and audio. Please contact the council on 0300 456 0100, by textphone on 01225 712500 or by email on [email protected]. Wiltshire Core Strategy Natural Environment Topic Paper 1 This paper is one of 18 topic papers, listed below, which form part of the evidence base in support of the emerging Wiltshire Core Strategy. These topic papers have been produced in order to present a coordinated view of some of the main evidence that has been considered in drafting the emerging Core Strategy. It is hoped that this will make it easier to understand how we had reached our conclusions. The papers are all available from the council website: Topic Paper TP1: Climate Change TP2: Housing TP3: Settlement Strategy TP4: Rural Issues (signposting paper) TP5: Natural Environment/Biodiversity TP6: Water Management/Flooding TP7: Retail TP8: Economy TP9: Planning Obligations TP10: Built and Historic Environment TP11:Transport TP12: Infrastructure TP13: Green Infrastructure TP14:Site Selection Process TP15:Military Issues TP16:Building Resilient Communities TP17: Housing Requirement Technical Paper TP18: Gypsy and Travellers 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................5 -

Public Opinion Survey – Devizes and Marlborough – Pewsey Section

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED / UNCLASSIFIED Public opinion survey – Devizes and Marlborough – Pewsey Section The Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner (OPCC) commissioned M.E.L. Research to consult local residents. During 2012/13 4408 Wiltshire residents completed the survey. A minimum of 384 people took part in each of the eleven policing sectors i ensuring that the results for each sector were significant ii . The aims of this survey are: o To measure public perception of Wiltshire Police and how communities are policed o To consult the public and enable the OPCC and Wiltshire Police to prepare policing plans o To enhance the OPCC and Wiltshire Police’s understanding of how policing influences people’s sense of security and wellbeing The report below sets out the results for the Pewsey section. A summary for the whole Force area will be available shortly on the Commissioner’s website. If you have any queries please contact the OPCC on the details below. Public perceptions linked to the Police and Crime Commissioner Priorities Pewsey Devizes and Wiltshire Police Force Section Marlborough Sector Area Feel safe when outside in their local area during the day 98.4% 96.6% 93.4% Feel safe when outside in their local area after dark 90.2% 75.1% 63.9% Satisfaction with the level of police visibility in their neighbourhood 62.3% 64.5% 59.1% Number Surveyed 61 384 4408 Population 13730 62680 684028 Key: significantly better than Wiltshire average* in line with Wiltshire average* significantly worse than Wiltshire average* * Wiltshire average -

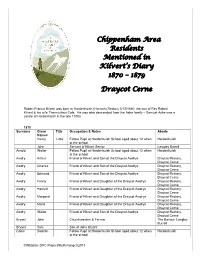

Draycot Cerne

Chippenham Area Residents Mentioned in Kilvert’s Diary 1870 – 1879 Draycot Cerne Robert Francis Kilvert was born at Hardenhuish (Harnish) Rectory 3/12/1840, the son of Rev Robert Kilvert & his wife Thermuthius Cole. He was also descended from the Ashe family – Samuel Ashe was a curate at Hardenhuish in the late 1700s. 1870 Surname Given Title Occupation & Notes Abode Names Henry ‘Little’ Fellow Pupil at Hardenhuish School aged about 12 when Hardenhuish at the school John Servant of Kilvert Senior Langley Burrell Arnold Walter Fellow Pupil at Hardenhuish School aged about 12 when Hardenhuish at the school Awdry Arthur Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Charles Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Edmund Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Fanny Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Harriett Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Margaret Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Maria Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Walter Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Bryant John Churchwarden & Farmer The Barrow, Langley Burrell Bryant Tom Son of John Bryant Coles Deacon Fellow Pupil at Hardenhuish School aged about 12 when Hardenhuish at the school ©Wiltshire -

Wiltshire and Swindon Waste Core Strategy

Wiltshire & Swindon Waste Core Strategy Development Plan Document July 2009 Alaistair Cunningham Celia Carrington Director, Economy and Enterprise Director of Environment and Wiltshire Council Regeneration Bythesea Road Swindon Borough Council County Hall Premier House Trowbridge Station Road Wiltshire Swindon BA14 8JN SN1 1TZ © Wiltshire Council ISBN 978-0-86080-538-0 i Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Key Characteristics of Wiltshire and Swindon 3 3. Waste Management in Wiltshire and Swindon: Issues and Challenges 11 4. Vision and Strategic Objectives 14 5. Strategies, Activities and Actions 18 6. Implementation, Monitoring and Review 28 Appendix 1 Glossary of Terms 35 Appendix 2 Development Control DPD Policy Areas 40 Appendix 3 Waste Local Plan (2005) Saved Policies 42 Appendix 4 Key Diagram 44 ii Executive Summary The Waste Core Strategy for Wiltshire and Swindon sets out the strategic planning policy framework for waste management over the next 20 years. The Waste Core Strategy forms one element of the Wiltshire and Swindon Minerals and Waste Development Framework. In this sense, the Core Strategy should be read in conjunction with national and regional policy as well as local policies –including the emerging Minerals and Waste Development Control Policies Development Plan Document (DPD) and the Waste Site Allocations DPD. The Strategy considers the key characteristics of Wiltshire and Swindon such as population trends, economic performance, landscape importance and cultural heritage. It identifies that approximately 68.6% of the Plan area is designated for its landscape and ecological importance, a key consideration within the Waste Core Strategy. The Strategy gives a summary of the current characteristics of waste management activities in Wiltshire and Swindon. -

TRANSFORMING PURTON PARISH Foresight and Resilience (Threats and Opportunities) Ps and Qs January 2013

TRANSFORMING PURTON PARISH Foresight and Resilience (Threats and Opportunities) Ps and Qs January 2013 1 | P a g e CONTENTS ABOUT Ps and Qs ............................................................................................................................... 3 FOR CLARIFICATION ......................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Sustainability ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. Key Parish Issues ........................................................................................................................ 9 3. Our Parish .................................................................................................................................. 11 3.1 Our Water ............................................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Our Food ............................................................................................................................... 19 3.3 Our Energy ............................................................................................................................ 26 3.4 Our Waste ............................................................................................................................ -

Clarendon Team News 20-04-2014

TEAM CHOIR for Holy Week and Easter Could all Team Choir members please email [email protected] so that we can build Clarendon TEAM news up a distribution list for the Team Choir. We can then let you know about any singing opportunities Clarendon Team Notices for Sunday 20th April 2014 that may come up in the Team. Thank you! Winterslow Christian Aid Lunches Services in Team Churches over the next two weeks Lunches at Truffles coffee shop on Thursday 1st May from 12 - 2pm in aid of Christian Aid. Readings: 20th April - Jeremiah 31.1-6 Acts 10.34-43 John 20.1-18 or Matthew 28.1-10 Whiteparish Music Festival (in aid of Church running costs) 27th April - Exodus 14.10-31; 15.20-21 Acts 2.14a,22-32 John 20.19-31 Tickets now on sale from Whiteparish Village Shop or The Music Room, Salisbury. Saturday 3rd May - “Jazz in the Church”, Wednesday 7th May - “Music for a Summer’s Night”, CHURCH 20th April - 27th April - Sunday 11th May - “Debussy to Disney”. To be held in All Saints Church, Whiteparish. Easter Day Second Sunday of Easter Please see the link for more info: www.clarendonteam.org/WHITEPARISHMUSICFESTIVAL2014.pdf ALDERBURY 9.30am All Age Easter Eucharist 9.30am Healing Eucharist 6pm Evening Prayer (Alt Utd Svc) Open Garden at Kings Farm - Proceeds to C of E, Methodist Church and Parkinsons Society WHADDON Sunday 4th May at Kings Farm, Livery Rd, West Winterslow from 2 - 4pm. There will be bring and at St Mary’s Hall with RC Preacher buy, raffles (Carol Hampton), Tombola (Janet Fry), books, bric-a-brac, tea and cakes. -

31 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

31 bus time schedule & line map 31 Malmesbury - Wootton Bassett - Swindon View In Website Mode The 31 bus line (Malmesbury - Wootton Bassett - Swindon) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Malmesbury: 9:00 AM - 7:00 PM (2) Swindon: 6:40 AM - 5:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 31 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 31 bus arriving. Direction: Malmesbury 31 bus Time Schedule 50 stops Malmesbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 9:00 AM - 7:00 PM Bus Station, Swindon New Bridge Close, Swindon Tuesday 9:00 AM - 7:00 PM Catherine Street, Swindon Wednesday 9:00 AM - 7:00 PM Henry Street, Swindon Thursday 9:00 AM - 7:00 PM Health Hydro, Swindon Friday 9:00 AM - 7:00 PM Faringdon Road, Swindon Saturday 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Birch Street, Swindon Park Lane, Swindon Dean Street, Swindon 21 Park Lane, Swindon 31 bus Info Direction: Malmesbury Great Western Outlet Village, Even Swindon Stops: 50 Penzance Drive, Swindon Trip Duration: 57 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Swindon, Catherine Paddington Drive, Bridgemead Street, Swindon, Health Hydro, Swindon, Birch Street, Swindon, Dean Street, Swindon, Great Western Mannington Roundabout, Mannington Outlet Village, Even Swindon, Paddington Drive, Bridgemead, Mannington Roundabout, Mannington, Blagrove Roundabout, Blagrove Blagrove Roundabout, Blagrove, M4 Roundabout, Freshbrook, Lydiard Fields Manor, Freshbrook, Sally M4 Roundabout, Freshbrook Pussey, Royal Wootton Bassett, Garraways, Royal Wootton Bassett, Swallows Mead, -

WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End Mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY. J WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs. Jas. Whiteparish, Salisbury St. Andrew, Salisbury Smith William, Broad Hinton, Swindon Strong George, Rowde, Devizes Sharpe Mrs. Henry, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William, Winsley, Bradford Strong James, Everleigh, Marlborough Sharpe Hy. Samuel, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William Hugh, Harpit, Wan- Strong Willialll, Draycot, Marlborough Sharps Frank, South Marston, Swindon borough, ShrivenhamR.S.O. (Berks) Strong William, Pewsey S.O Sharps Robert, South Marston, Swindon Snelgar John, Whiteparish, Salisbury Stubble George, Colerne, Chippenham Sharps W. H. South Marston, Swindon Snelgrove David, Chirton, De,·izes Sumbler John, Seend, Melksham Sheate James, Melksham Snook Brothers, Urchfont, Devizes SummersJ.&J. South Wraxhall,Bradfrd Shefford James, Wilton, Marlborough Snook Albert, South Marston, Swindon Summers Edwd. Wingfield rd. Trowbrdg ShepherdMrs.S.Sth.Burcombe,Salisbury Snook Mrs. Francis, Rowde, Devizes Sutton Edwd. Pry, Purton, Swindon Sheppard E.BarfordSt.Martin,Salisbury Snook George, South Marston, Swindon Sutton Fredk. Brinkworth, Chippenham Shergold John Hy. Chihnark, Salisbury EnookHerbert,Wick,Hannington,Swndn Sutton F. Packhorse, Purton, Swindon ·Sbewring George, Chippenham Snook Joseph, Sedghill, Shaftesbury Sutton Job, West Dean, Salisbury Sidford Frank, Wilsford & Lake farms, Snook Miss Mary, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton·John lllake, Winterbourne Gun- Wilsford, Salisbury Snook Thomas, Urchfont, Devizes ner, Salisbury "Sidford Fdk.Faulston,Bishopstn.Salisbry Snook Worthr, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton Josiah, Haydon, Swindon Sidford James, South Newton, Salisbury Somerset J. Milton Lilborne, Pewsey S.O Sutton Thomas Blake, Hurdcott, Winter Bimkins Job, Bentham, Purton, Swindon Spackman Edward, Axrord, Hungerford bourne Earls, Salisbury Simmons T. GreatSomerford, Chippenhm Spackman Ed. Tytherton, Chippenham Sutton William, West Ha.rnham,Salisbry .Simms Mrs. -

Wilsomdor, Chapel Hill, West Grimstead, Price: £585,000 Salisbury, Wiltshire, Sp5 3Sg

WILSOMDOR, CHAPEL HILL, WEST GRIMSTEAD, PRICE: £585,000 SALISBURY, WILTSHIRE, SP5 3SG A BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED DETACHED HOUSE WITH EXCELLENT ANNEXE AND SOUTH FACING GARDEN ON THE EAST SIDE OF SALISBURY DIRECTIONS: From Salisbury proceed out south east on the A36 Southampton Road and continue along the Alderbury bypass until you see a turning on the left signposted The Grimsteads. Turn off here, branch left at the T-junction and continue along here until you come to another junction and then turn left into Crockford Lane. Proceed along here until you come to the railway bridge, turn right into Chapel Hill and the property will be found immediately on the right hand side. DESCRIPTION: This is a superb detached house with the benefit of a one bedroom annexe, located in a very popular village on the eastern side of Salisbury. The original house dates back to the early 1970s, was extended in 2016 and has been completely refurbished in recent years. Construction is of brick elevations under a tile roof and the house has the benefit of LPG central heating, part of which is under floor, as well as full double glazing. To the side of the house the former double garage has been converted into an excellent one bedroom annexe with a kitchen/breakfast room, living room, dressing room, shower room and double bedroom on the first floor. There is also parking for four cars to the front of the annexe and an attractive south facing garden with patio and lawn and views over open fields. LOCATION: The property is located in West Grimstead some five miles to the east of the city of Salisbury.