Beginning Reading and Writing. Language and Literacy Series. INSTITUTION International Reading Association, Newark, DE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2020Fall 2020

HarE JoHn HarE Students dressed is a freelance illustrator and in deep-sea diving graphic designer who works on Field Trip suits travel to the a range of projects. He lives in ocean deep in a yellow Gladstone, Missouri, with his submarine school bus. wife and two children. When they get there, they are introduced to creatures like T PRAISE FOR Field Trip to the Moon o luminescent squids and giant T he isopods, and discover an old ocean deep shipwreck. But when it’s time to return to the submarine bus, one student lingers to take a photo of a treasure chest and A Junior Library Guild Selection falls into a deep ravine. Luckily, A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year the child is entertained by a The Horn Book Fanfare List mysterious sea creature until ★ “Hare’s picture book debut is a winner . being retrieved by the teacher. A beautifully done wordless story about BOOKS FERGUSON MARGARET In his follow-up to Field Trip to a field trip to the moon with a sweet and funny alien encounter.”—School Library the Moon, John Hare’s rich, Journal, starred review atmospheric art in this wordless “[An] auspicious debut presents a world picture book invites children where a yellow crayon box shines Holiday House to imagine themselves in the like a beacon.”—Booklist story—a story full of surprises. MARGARET FERGUSON BOOKS BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE US $17.99$17.99 / CAN / CAN $23.99 $23.99 ISBN: 978-0-8234-4630-8 Holiday House Publishing, Inc. 5 1 7 9 9 HolidayHouse.com EAN Fall 2020 Printed in China 9 780823 446308 0408 Reinforced Illustration © 2020 by John Hare from Field Trip to the Ocean Deep HOLIDAY HOUSE Apples Gail Gibbons Summary Find out where your favorite crunchy, refreshing fruit comes from in this snack-sized book. -

Communication Station: Tune in at Your Library! 1997 Florida Library Youth Program

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 402 947 IR 056 248 AUTHOR Mattair, Valerie Lennox, Comp.; Broderick, Bridgid, Comp. TITLE Communication Station: Tune In at Your Library! 1997 Florida Library Youth Program. INSTITUTION Florida Dept. of State, Tallahassee. Div. of Library and Information Services. PUB DATE [96] NOTE 270p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Books; Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; *Library Services; Program Development; Public Libraries; *Reading Programs; *Recreational Programs; Recreational Reading; Summer Programs; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *Florida; Library Services and Construction Act ABSTRACT Funded by the Library Services and Construction Act, the 1997 Florida Library Youth Program is an extension of the successful and long-running Florida Summer Library Program to help librarians provide year-round programs for elementary school-aged children. The goal of the program is to introduce children to the library and its services, and to encourage them to read books. The manual is intended as a guide for program coordinators and librarians. This edition focuses on the many ways that people communicate, in the present, past, and future. The manual includes the following sections: (1) What Do You Say?;(2) Drop a Line; (3) Express Yourself;(4) Over the Wire;(5) Code Talk;(6) Mixed Messages;(7) What's in a Name?;(8) Messages from Beyond;(9) Animal Banter; and (10) Voices from the Past. Each section includes the following activities, with book and presentation ideas recommended for each: storytelling, presentations, "read-alouds," poetry, jokes, riddles, songs, book-talks, informational books, "read-alones," crafts, activities, displays, community resources, music, recordings, films, videos, additional professional resources, and craft and game sheets. -

Tarzan in the Early-20Th Century French Fantasy Landscape By

Wesleyan University The Honors College The Missing Link: Tarzan in the Early-20th Century French Fantasy Landscape by Medha Swaminathan Class of 2019 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in French Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Embracing the Invented in the “Benevolent” Colonial ................................................ 9 Imagining “Africa” ..................................................................................................... 19 Le Tour du Monde en Un Jour: Tarzan and the 1930s Paris Colonial Exhibitions .... 36 “Civilization” vs. “Civilized” vs. “Savage” ................................................................ 49 Homme Idéal or Missing Link? Fetish, Fascination, and Fear in French Eugenics ... 57 Sex, Youth, Beauty, Valor, and the Légionnaire ........................................................ 70 Saturnin Farandoul: Tarzan’s French Foil? ................................................................ 81 “Comment dit-on sites de rêve en anglais ?” .............................................................. 96 References ................................................................................................................. 100 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without an incredible amount -

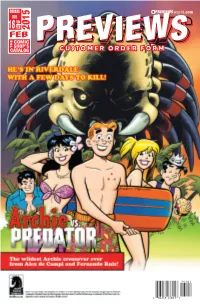

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

September-0Ctober 2013

september-0ctober 2013 On September 10, 1988, Museum of the As we enter our 25th anniversary year, I while doing the rounds through the Moving Image opened its doors to the can tell you that it has been a thrilling ride galleries, and then repair a video arcade public. At the time, years before the for the Museum, at least as action-packed game. He was a true professional, but will promise of the Internet and digital media as The Great Train Robbery. We have be best remembered as a great husband, were captured in the now-quaint phrase transformed and expanded over the years father, and friend, and he will be missed. “Information Superhighway,” the idea of a to serve a growing audience and to offer an We will pay tribute to Richie on October Museum, built on an historic site for movie increasingly ambitious slate of exhibitions, 4 at an event to mark the opening of a production, that would take a unified view screenings, and education programs. wonderful photo exhibit, The Booth, about of the disparate worlds of film, television, Our film programs range from the best projectionists and their workspaces. and video games, seemed as audacious as of classic Hollywood—as in our complete it was unprecedented. There was, simply, Howard Hawks retrospective—to the best Richie was a great showman; more than no museum like it in the world. It was an of contemporary world cinema—as in our anything at the Museum, he was obsessed innovative blend of a science museum, focus on the great French director Claire with making sure that we put on the best an art museum, a technology museum, Denis. -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness. -

Amazon, E-Books and New Business Models

AUTHORS GUILD Winter 2015 BULLETIN The Big Grab: T. J. Stiles On How Publishing’s New Math Devalues Writers’ Work Q&A with Executive Director Mary Rasenberger Roxana Robinson on Compassion’s Place in Prose Annual Meeting Report LETTER TO THE EDITOR our timely Q&A with author CJ Lyons was uplift- Bulletin, however, should feature an author who Ying and inspiring (Summer, 2014). Clearly, Lyons’s is beating the odds with guts, grit and innovation. success as an author is due to her winning mindset. Somebody saying Yes, you can! (Not go hide under the That’s what authors need most from the Authors bed.) Lyons did that and it was a refreshing change. Guild. Less doom and gloom. More daring hope and Now give us more. Thanks for your consideration. enthusiasm. With how-to’s. Onward! Sure, industry news is often depressing. Every — Patricia Raybon, Aurora, CO ALONG PUBLISHERS ROW By Campbell Geeslin “ remarkable thing about the novel is that it can with Harper Collins. The first book will be Seveneves, A incorporate almost anything,” wrote Thad due out in May. The novel, PW said, is about “the sur- Ziolkowski in Sunday’s New York Times Book Review. vivors of a global disaster which nearly caused the ex- He directs the writing program at Pratt Institute and is tinction of life on the planet.” the author of a novel, Wichita. The second book, to be written with Nicole The novel, he said, “can contain essays, short sto- Galland, is set for 2017. ries, mock memoirs, screenplays, e-mails—and re- Stephenson has written more than a dozen novels, main a novel. -

Universiv Micrcsilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tlie sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Northportcollectbib2012.Pdf (593.1Kb)

Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection Stony Brook University Stony Brook, N.Y. Compiled by Karen D’Angelo Library Technical Services Stony Brook University 2012 All of the materials included in this bibliography provide valuable educational opportunities to learn more about First Nations Peoples. The Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection has been relocated to the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library at Stony Brook University. The bibliography can be viewed at the Stony Brook web page: https://dspace.sunyconnect.suny.edu/handle/1951/42805 You can ask your local public library if they have copies of the materials. In addition to the Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection other materials on Native American history and culture can be found at the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library. You can search the STARS catalog http://www.stonybrook.edu/~library/index.html or ask a librarian for assistance. The Stony Brook main library can be contacted at: (631) 632-7100. 2nd annual Native American Indian Ceremony. – November 7, 2001. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 2nd annual Native American Ceremony. – November 7, 2001. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 2nd annual video conference VHA Bronx : emerging issues in SW and aging “differences do make a difference” – June 5, 2002. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 3rd annual Native American ceremony. – Novermber 6, 2002. VHS – 60 min. **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 7th annual VAMC Northport Native American heritage IEEO program with Josephine Smith of Shinnecock Nation : speaking on traditional medicine. DVD **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137* 8th annual VAMC tribute to Native American Indian employees and veterans “American Indian Cultural Practices in Healing. -

Northportcollectbib2010.Pdf (450.4Kb)

Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection Stony Brook University Stony Brook, N.Y. Compiled by Karen D’Angelo Library Technical Services Stony Brook University 2010 All of the materials included in this bibliography provide valuable educational opportunities to learn more about First Nations Peoples. The Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection has been relocated to the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library at Stony Brook University. The bibliography can be viewed at the Stony Brook web page: https://dspace.sunyconnect.suny.edu/handle/1951/42805 You can ask your local public library if they have copies of the materials. In addition to the Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection other materials on Native American history and culture can be found at the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library. You can search the STARS catalog http://www.stonybrook.edu/~library/index.html or ask a librarian for assistance. The Stony Brook main library can be contacted at: (631) 632-7100. 2nd annual Native American Indian Ceremony. – November 7, 2001. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 2nd annual Native American Ceremony. – November 7, 2001. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 2nd annual video conference VHA Bronx : emerging issues in SW and aging “differences do make a difference” – June 5, 2002. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 3rd annual Native American ceremony. – Novermber 6, 2002. VHS – 60 min. **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 7th annual VAMC Northport Native American heritage IEEO program with Josephine Smith of Shinnecock Nation : speaking on traditional medicine. DVD **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137* 8th annual VAMC tribute to Native American Indian employees and veterans “American Indian Cultural Practices in Healing. -

John Ford and the Author Theory: Contribution of Anglo

RUTH GUTIÉRREZ DELGADO [email protected] COMUNICACIÓN Y SOCIEDAD Vol. XXV • Núm. 1 • 2012 • 39-58 Rut Gutiérrez Delgado, Lecturer in Epistemilogy of Communication and Fiction Script I. University of Navarre. Faculty of Communication. 31080 Pamplona. John Ford and the Author Theory: contribution of Anglo-Saxon criticism towards debate John Ford y la Teoría del Autor: la aportación de la crítica anglosajona al debate Recibido: 23 de septiembre de 2011 Aceptado: 24 de octubre de 2011 AbstRAct: Tradition in cinema criti- resumen: La tradición de la crítica ci- cism has given excessive importance nematográfica ha otorgado un papel to Cahiers du Cinéma in relation to excesivo a Cahiers du Cinéma en lo Fordian authorship. However, it was que respecta a la autoría fordiana. in fact the ‘Turkish youths’ (Cahiers’s Si bien, fueron los “jóvenes turcos” critics) the ones who not only un- (los críticos de Cahiers) los que ra- dertook radical theories as regards dicalizaron las posturas sobre el au- 39 cinema auteur but they were also teur cinematográfico y decidieron en the ones who decided what was the qué momento correspondía erigir a appropriate moment in which to es- Ford en autor, desarrollando amplios tablish Ford as an author, develop- argumentarios sobre la cuestión, ing wide arguments on that issue. en un plano más discreto pero muy Vol. XXV • Nº 1 C y S • 2012 On a rather discreet level, but much anterior, fue la revista británica Se- earlier in time, the British magazine quence la que defendió a finales de Sequence defended with strong rea- los cuarenta la causa fordiana con soning the Fordian cause in the late razones sólidas. -

![Learning from John Ford. History, Geography, and Epic Storytelling in the Works of Peter Handke Zumhof, Tim [Hrsg.]; Johnson, Nicholas K](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9530/learning-from-john-ford-history-geography-and-epic-storytelling-in-the-works-of-peter-handke-zumhof-tim-hrsg-johnson-nicholas-k-2869530.webp)

Learning from John Ford. History, Geography, and Epic Storytelling in the Works of Peter Handke Zumhof, Tim [Hrsg.]; Johnson, Nicholas K

Carstensen, Thorsten Learning from John Ford. History, geography, and epic storytelling in the works of Peter Handke Zumhof, Tim [Hrsg.]; Johnson, Nicholas K. [Hrsg.]: Show, don't tell. Education and historical representations on stage and screen in Germany and the USA. Bad Heilbrunn : Verlag Julius Klinkhardt 2020, S. 131-159. - (Studien zur Deutsch-Amerikanischen Bildungsgeschichte / Studies in German-American Educational History) Empfohlene Zitierung/ Suggested Citation: Carstensen, Thorsten: Learning from John Ford. History, geography, and epic storytelling in the works of Peter Handke - In: Zumhof, Tim [Hrsg.]; Johnson, Nicholas K. [Hrsg.]: Show, don't tell. Education and historical representations on stage and screen in Germany and the USA. Bad Heilbrunn : Verlag Julius Klinkhardt 2020, S. 131-159 - URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-205158 - DOI: 10.35468/5828_09 http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-205158 http://dx.doi.org/10.35468/5828_09 in Kooperation mit / in cooperation with: http://www.klinkhardt.de Nutzungsbedingungen Terms of use Dieses Dokument steht unter folgender Creative Commons-Lizenz: This document is published under following Creative Commons-License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de - Sie dürfen das http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en - You may copy, Werk bzw. den Inhalt unter folgenden Bedingungen vervielfältigen, verbreiten distribute and transmit, adapt or exhibit the work in the public and alter, und öffentlich zugänglich machen sowie Abwandlungen und Bearbeitungen transform or change this work as long as you attribute the work in the manner des Werkes bzw. Inhaltes anfertigen: Sie müssen den Namen des specified by the author or licensor.