The Use of Address Terms Among Algerian Arabic Speakers in Touat Speech Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGRICULTURAL DEMONSTRATION PILOTS in the Sass Basin

ELABORATION OF OPERATIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS AGRICULTURAL DEMONSTRATION PILOTS FOR A SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF THE WATER RESOURCES SASS III IN THE SASS BASIN OF THE NORTH WESTERN SAHARA AQUIFER SYSTEM July 2010 – June 2014 The North-Western Sahara Aquifer System (SASS) is a basin of over 1,000,000 km2 shared by three countries (Algeria, Tunisia, Libya) whose water reserves are substantial with an almost fossilized aspect. The implementation of “Agricultural Demonstration Pilots” within the framework of the SASS III project was intended to demonstrate within a participatory ap- proach, the feasibility, effectiveness and efficiency of technical solutions to local problems of unsustainability management and operation of the SASS resource in irrigation in the three countries sharing the resource. Six agricultural demonstration pilots at farm scale level, with different themes, were implemented by farmers themselves in the three countries. The technical innovations introduced aimed at the intensification of cropping systems, water saving and the improvement of the resource’s valorization through the selection of high added value crops. The results obtained after two crops in the three countries help confirm the availability of efficient technical solutions for the renovation of cropping sys- tems and making them viable at farm level. What remains to be done, however, AGRICULTURAL DEMONSTRATION is validating these results and making them reliable on a larger spatial scale in pilot “production systems” integrating the various local structural constraints to PILOTS IN THE SASS BASIN the development of irrigation in the SASS area. SIN A B Towards a Sustainable and Profitable SS A S Agriculture in the Sahara THE IN PILOTS ANRH DGRE GWA TION A DEMONSTR L A ISBN : 978-9973-856-86-9 GRICULTUR Sahara and Sahel Observatory A - III Bd du Leader Y. -

14 20 Moharram 1431 6 Janvier 2010 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA

14 20 Moharram 1431 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE N° 01 6 janvier 2010 ANNEXE CONSISTANCE DES OFFICES DES ETABLISSEMENTS DE JEUNES DE WILAYAS DENOMINATION WILAYAS N° DE L’ETABLISSEMENT DE JEUNES IMPLANTATION ADRAR 1.1 Maison de jeunes d’Adrar Quartier Ouled Ali, commune d’Adrar 1.2 Maison de jeunes de Timimoun Commune de Timimoun 1.3 Maison de jeunes de Aougrout Commune d’Aougrout 1.4 Maison de jeunes de Timimoun Commune de Timimoun 1.5 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune de Sali 1.6 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune de Tamest 1.7 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune de Fenoughil 1.8 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune de Tsabit 1.9 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune de Tamantit 1.10 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune d’Aougrout 1.11 Complexe sportif de proximité Commune de Zaouiet Kounta CHLEF 2.1 Maison de jeunes - Hay Bensouna Hay Bensouna, commune de Chlef 2.2 Maison de jeunes - Hay An Nasr Hay An Nasr zone 3, commune de Chlef 2.3 Maison de jeunes - Hay Lala Aouda Hay Lala Aouda, commune de Chlef 2.4 Maison de jeunes - Frères Abbad Route de Sandjas, commune de Chlef 2.5 Maison de jeunes - Hay Badr Hay Badr, commune de Chlef 2.6 Maison de jeunes de Oued Fodda Rue du 1er novembre 1954, commune de Oued Fodda 2.7 Maison de jeunes d’El Karimia Commune d’El Karimia 2.8 Maison de jeunes de Chettia Commune de Chettia 2.9 Maison de jeunes de Ténès Route de Cherchell, commune de Ténès 2.10 Maison de jeunes de Boukadir Commune de Boukadir 2.11 Maison de jeunes de Chlef Route d’Alger, commune de Chlef 2.12 Maison -

DYNAMIQUES ET MUTATIONS TERRITORIALES DU SAHARA ALGERIEN VERS DE NOUVELLES APPROCHES FONDÉES SUR L’OBSERVATION Yaël Kouzmine

DYNAMIQUES ET MUTATIONS TERRITORIALES DU SAHARA ALGERIEN VERS DE NOUVELLES APPROCHES FONDÉES SUR L’OBSERVATION Yaël Kouzmine To cite this version: Yaël Kouzmine. DYNAMIQUES ET MUTATIONS TERRITORIALES DU SAHARA ALGERIEN VERS DE NOUVELLES APPROCHES FONDÉES SUR L’OBSERVATION. Géographie. Université de Franche-Comté, 2007. Français. tel-00256791 HAL Id: tel-00256791 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00256791 Submitted on 18 Feb 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ DE FRANCHE-COMTÉ ÉCOLE DOCTORALE « LANGAGES, ESPACES, TEMPS, SOCIÉTÉS » Thèse en vue de l’obtention du titre de docteur en GÉOGRAPHIE DYNAMIQUES ET MUTATIONS TERRITORIALES DU SAHARA ALGERIEN VERS DE NOUVELLES APPROCHES FONDÉES SUR L’OBSERVATION Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Yaël KOUZMINE Le 17 décembre 2007 Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Marie-Hélène DE SÈDE-MARCEAU Membres du Jury : Abed BENDJELID, Professeur à l’université d’Oran Marie-Hélène DE SÈDE-MARCEAU, Professeur à l’université de Franche-Comté Jacques FONTAINE, Maître de conférences à -

Mémoire De Master En Sciences Économiques Spécialité : Management Territoriale Et Ingénierie De Projet Option : Économie Sociale Et Solidaire

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE Université Mouloud Mammeri Tizi Ouzou Faculté des sciences économiques commerciales et des sciences de gestion Département des sciences économiques Laboratoire REDYL Mémoire De master en sciences économiques Spécialité : management territoriale et ingénierie de projet Option : économie sociale et solidaire Caractérisation de la gestion de l’eau en tant que bien communs dans l’espace saharien Algérien mode de gouvernance du système traditionnel des foggaras Présenté par : Sous-direction : GHAOUI Nawal Pr. AHMED ZAID Malika HADJALI Sara Année universitaire : 2016/2017 Caractérisation de la gestion de l’eau en tant que bien communs dans l’espace saharien Algérien mode de gouvernance du système traditionnel des foggaras Résumé du mémoire : Depuis quelques années, la ressource en eau n’est plus seulement appréhendée en termes de disponibilité et d’usage mais aussi comme un bien commun à transmettre aux générations futures .Ces deux conceptions de l’eau demeurent grandement contradictoire malgré les efforts déployés pour concilier viabilité économique et participation sociale. Dans ce contexte, au Sahara algérien le système traditionnel d’irrigation « foggara » constitue un élément majeur pour comprendre la complexité de la relation entre les ressources en eau disponibles, la gestion et la gouvernance de la ressource, son usage et la prise de décision. Mots clés : bien commun, gouvernance, ressource en eau, foggara. Dédicaces Je dédie ce modeste travail à : A mes très chers parents .Aucun hommage ne pourrait être à la hauteur de l’amour dont ils ne cessent de me combler. Que dieu leur procure bonne santé et longue vie. -

Essaie De Presentation

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIEENE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL INSTITUT NATIONAL DES SOLS DE L’IRRIGATION ET DU DRAINAGE ESSAI DE PRESENTATION D’UNE TECHNIQUE D’IRRIGATION TRADITIONNELLE DANS LA WILAYA D’ADRAR : LA « FOGGARA » SOMMAIRE Introduction CHAPITRE -I- 1-1/ Définition d’une foggara 1-2/ Historique CHAPITRE –II- 2-1/ Situation géographique 2-2/ Caractères généraux 2-2-1/ Climatologie i/ température ii/ les vents iii/ la pluviométrie 2-2-2/ Géologie 2-2-3/ Hydrogéologie 2-2-4/ Végétation CHAPITRE –III- 3-1/ Inventaire des foggaras taries 3-2/ Les causes du tarissement des foggaras 3-2-1/ Les problèmes liés à la foggara 3-2-2/ Les problèmes liés à l’exploitation des foggaras. Conclusion Recommandations Bibliographie 1- « Mobilisation de la ressource par le système des foggaras ». Par Hammadi Ahmed El Hadj KOBORI Iwao.1993. 2- «Irrigation et Structure agraire à Tamentit (Touat) » Travaux de l’Institut de Recherches Sahariennes Tome XXI.1962. 3-« Une Oasis à foggaras ‘Tamentit) » Par J. Vallet 1968 4- Inventaires des foggaras (ANRH de la wilaya d’Adrar).2001 5- Etude du tarissement des foggaras dans la wilaya d’Adrar ANRH2003. 6- Les villes du sud, vision du développement durable, Ministère de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Equipement, Alger, 1998, page 46 7- « Les foggaras du Touat » par M. Combés Introduction : Issue du découpage administratif de 1974, la Wilaya d’Adrar s’étend sur la partie Nord du Sud Ouest Algérien, couvrant ainsi une superficie de 427.968 km2 soit 17,97% du territoire national. -

Characterization of Two Oasis Luzerns (El Menea, Tamentit) at the Floral Bud and Early Flowering Stages

Crimson Publishers Research Article Wings to the Research Characterization of Two Oasis Luzerns (El Menea, Tamentit) at the Floral Bud and Early Flowering Stages Alane Farida1*, Moussab Karima B1, Chabaca Rabeha2 and Abdelguerfi Aissa2 1Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique d’Algérie (INRAA) Baraki; Division productions animales, Algeria ISSN: 2578-0336 2Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Agronomie (ENSA), Algeria Abstract Adrar’s oasis with great ingenuity knew, taking into account the harshness of pedoclimatic conditions, to adapt the means of production to Lucerne. We compared 2 oasis alfalfa cultivars through biometric is correlated with the phenological stages. Indeed, the older the plant, the greater the assimilation of and chemical parameters at two phenological floral and early flowering stages. The quality of these cultivarmineral atmatter; the same But stagethe needs at the at second the floral mowing. button The stage ratio are of higherleaves tothan stems at the in greenearly bloomand dry stage. is higher The highest value of MAT is 38.7% in El Menea at the floral bud stage and the lowest is 20.8% in the same this ratio, in dry, decreases from 1.51 to 1.04. With the same planting rate, the Tamentit population has *1Corresponding author: Alane Farida, in Tamentit than in El Menea in both stages, resulting in better digestibility. At the initial flowering stage Institut National de la Recherche values of the other 2 parameters, height of stems and number of stems per square meter. The summer Agronomique d’Algérie (INRAA) Baraki; seasonan average and plantthe second per square year ofmeter operation lower encouragethan El Menea, the increase ie 15.8 atin thethe floralnumber bud of stage, stems as and well the as spring lower Division productions animales, Algeria season favors the height of the stems. -

La Lettre De Solimed

La lettre de SoliMed Lettre n°14 Mai 2008 EDITO PRESENTATION DE SOLIMED Vers de nouveaux défis ! EN QUELQUES MOTS Constituée en 1994 par des Quatorze ans après sa création, SoliMed, fidèle à ses débuts, conti- cadres et médecins algériens nue d’œuvrer à l’émergence d’un élan de solidarité en faveur des per- résidents en France qui souhai- sonnes nécessiteuses et malades qui vivent en Algérie. Dans cette taient venir en aide aux mala- perspective, nous organisons ou participons à des missions médica- des démunis algériens, Soli- les qui ont pour objectif d’améliorer la couverture sanitaire des popula- Med a traversé depuis sa créa- tions défavorisées dans le Sud Algérien. Nous montons également tion différentes étapes. De des projets de solidarité qui soutiennent la formation et l’information 1994 à 2004, nous avons mis des professionnels de santé et qui encouragent l’éducation sanitaire l’accent sur l’envoi de matériel en Algérie. Nous développons aussi des partenariats afin de venir en médical et de médicaments à aide aux malades algériens qui ne peuvent se procurer leurs médica- divers services hospitaliers et ments en raison de leur coût excessif ou de leur pénurie. associations. A partir de 2005, Portée par un réseau de quelque 2500 sympathisants, SoliMed re- nous avons opté pour l’organi- pose sur le travail d’une cinquantaine de bénévoles qui se réunissent sation de missions médicales mensuellement afin d’initier des projets et de faire avancer les actions dans des zones défavorisées en cours. SoliMed parvient à soutenir financièrement ses initiatives de l’Algérie. -

Aba Nombre Circonscriptions Électoralcs Et Composition En Communes De Siéges & Pourvoir

25ame ANNEE. — N° 44 Mercredi 29 octobre 1986 Ay\j SI AS gal ABAN bic SeMo, ObVel , - TUNIGIE ABONNEMENT ANNUEL ‘ALGERIE MAROC ETRANGER DIRECTION ET REDACTION: MAURITANIE SECRETARIAT GENERAL Abonnements et publicité : Edition originale .. .. .. .. .. 100 D.A. 150 DA. Edition originale IMPRIMERIE OFFICIELLE et satraduction........ .. 200 D.A. 300 DA. 7 9 et 13 Av. A. Benbarek — ALGER (frais d'expédition | tg}, ; 65-18-15 a 17 — C.C.P. 3200-50 ALGER en sus) Edition originale, le numéro : 2,50 dinars ; Edition originale et sa traduction, le numéro : 5 dinars. — Numéros des années antérleures : suivant baréme. Les tables sont fourntes gratul »ment aux abonnés. Priére dé joindre les derniéres bandes . pour renouveliement et réclamation. Changement d'adresse : ajouter 3 dinars. Tarif des insertions : 20 dinars la ligne JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE CONVENTIONS ET ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX LOIS, ORDONNANCES ET DECRETS ARRETES, DECISIONS, CIRCULAIRES, AVIS, COMMUNICATIONS ET ANNONCES (TRADUCTION FRANGAISE) SOMMAIRE DECRETS des ceuvres sociales au ministére de fa protection sociale, p. 1230. Décret n° 86-265 du 28 octobre 1986 déterminant les circonscriptions électorales et le nombre de Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux siéges & pourvoir pour l’élection a l’Assemblée fonctions du directeur des constructions au populaire nationale, p. 1217. , ministére de la formation professionnelle et du travail, p. 1230. DECISIONS INDIVIDUELLES Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux fonctions du directeur général da la planification Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux et de. la gestion industrielle au ministére de fonctions du directeur de la sécurité sociale et lindustrie lourde,.p. -

ALGERIE POTENTIEL EN HYDROCARBURES RÉSERVES PAR BASSIN 50 Mds Bep 15Mbep 15 Mbep (En Mds Bep)

ALGERIE POTENTIEL EN HYDROCARBURES RÉSERVES PAR BASSIN 50 Mds Bep 15Mbep 15 Mbep (en Mds Bep) 1 Mbep 10 Mbep HMD: 15 HRM: 15 3 Mbep 9 Mbep BERK.:10 ILLIZI:9 1 Mbep OMYA:1 1 Mbep 1,5 Mbep AHN.:1,5 6,5 Mds Bep TIMI.:3 SBAA:1 REGG:1 CARTE PETROLIERE DES BASSINS TOTAL: 56,5 Algeria Gas Exploration Trends (Evaluation par un opérateur indépendant) Circum HRM: Conventional Reservoir Gas Exploration Rich Gas condnesates Triassic and Palaeozoic Plays Reserve Potential 50 – 100 TCF ?? 50-70 TCFG Potential Tight Gas Exploration Potential Reserve Potential 100 – 200 TCF Berkine Basin: Rich Gas Condensates Gourara Basin: Upr Dev / Carb Ssts Dry Gas 20-70 TCFG Potential Palaeozoic plays 10-25 TCFG Pot Illizi Basin: Tindouf / Reggane Lean Gas Condensates Dry Gas C/O ssts Fault seals Deep basin and basin 10-20 TCFG potential margin Plays Ahnet Basin: 50-100 TCFG Potential Dry Gas Palaeozoic Ssts 5-25 TCF Potential RESSOURCES SPECULATIVES EN PLACE (dans le sous-sol !!!) • CONVENTIONNELLES : GAZ : SH : 2.800 à 6.000 Mds M3 PETROLE : SH : 3 Mds Tonnes HC liquides • NON CONVENTIONNELLES : - GAZ : SH : 25.000 à 140.000 Mds M3 ALNAFT : 126.000 à 168.000 Mds M3 - PETROLE : SH : 248 Mds barils (30 Mds Tonnes) ALNAFT : 170 Mds barils (24 Mds Tonnes) RESERVES RECUPERABLES : 10 à 20% ??? POTENTIEL EN GAZ DE SCHISTE Les études & travaux actuels couvrent une surface de moins de 200.000 Km2 sur une région désertique de plus d’un million Km2 SILURIEN Réf: Sonatrach FRASNIEN 17/11/2014 A. -

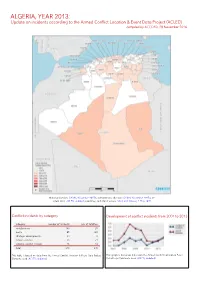

ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 28 November 2016

ALGERIA, YEAR 2013: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 28 November 2016 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2004 to 2013 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 149 25 battle 85 282 strategic developments 34 0 remote violence 26 21 violence against civilians 16 12 total 310 340 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). ALGERIA, YEAR 2013: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 28 NOVEMBER 2016 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Adrar, 27 incidents killing 62 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Adrar, Bordj Badji Mokhtar, Ouaina, Sbaa, Tanezrouft, Tanezrouft Desert, Timiaouine, Timimoun. In Alger, 56 incidents killing 8 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Algiers, Bab El Oued, Baraki, Kouba, Said Hamdine. -

Bouda - Ouled Ahmed Timmi Tsabit - Sebâa- Fenoughil- Temantit- Temest

COMPETENCE TERRITORIALE DES COURS Cour d’Adrar Cour Tribunaux Communes Adrar Adrar - Bouda - Ouled Ahmed Timmi Tsabit - Sebâa- Fenoughil- Temantit- Temest. Timimoun Timimoun - Ouled Said - Ouled Aissa Aougrout - Deldoul - Charouine - Adrar Metarfa - Tinerkouk - Talmine - Ksar kaddour. Bordj Badji Bordj Badj Mokhtar Timiaouine Mokhtar Reggane Reggane - Sali - Zaouiet Kounta - In Zghmir. Aoulef Aoulef - Timekten Akabli - Tit. Cour de Laghouat Cour Tribunaux Communes Laghouat Laghouat-Ksar El Hirane-Mekhareg-Sidi Makhelouf - Hassi Delâa – Hassi R'Mel - - El Assafia - Kheneg. Aïn Madhi Aïn Madhi – Tadjmout - El Houaita - El Ghicha - Oued M'zi - Tadjrouna Laghouat Aflou Aflou - Gueltat Sidi Saâd - Aïn Sidi Ali - Beidha - Brida –Hadj Mechri - Sebgag - Taouiala - Oued Morra – Sidi Bouzid-. Cour de Ghardaïa Cour Tribunaux Communes Ghardaia Ghardaïa-Dhayet Ben Dhahoua- El Atteuf- Bounoura. El Guerrara El Guerrara - Ghardaia Berriane Sans changement Metlili Sans changement El Meniaa Sans changement Cour de Blida Cour Tribunaux Communes Blida Blida - Ouled Yaïch - Chréa - Bouarfa - Béni Mered. Boufarik Boufarik - Soumaa - Bouinan - Chebli - Bougara - Ben Khellil – Ouled Blida Selama - Guerrouaou – Hammam Melouane. El Affroun El Affroun - Mouzaia - Oued El Alleug - Chiffa - Oued Djer – Beni Tamou - Aïn Romana. Larbaa Larbâa - Meftah - Souhane - Djebabra. Cour de Tipaza Cour Tribunaux Communes Tipaza Tipaza - Nador - Sidi Rached - Aïn Tagourait - Menaceur - Sidi Amar. Kolea Koléa - Douaouda - Fouka – Bou Ismaïl - Khemisti – Bou Haroum - Chaïba – Attatba. Hadjout Hadjout - Meurad - Ahmar EL Aïn - Bourkika. Tipaza Cherchell Cherchell - Gouraya - Damous - Larhat - Aghbal - Sidi Ghilès - Messelmoun - Sidi Semaine – Beni Milleuk - Hadjerat Ennous. Cour de Tamenghasset Cour Tribunaux Communes Tamenghasset Tamenghasset - Abalessa - Idlès - Tazrouk - In Amguel - Tin Zaouatine. Tamenghasset In Salah Sans changement In Guezzam In Guezzam. -

Future of an Oasis to the Detriment of a Hydraulic Monument “Case of Timimoun”

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Engineering & Technology (IMPACT: IJRET) ISSN(E): 2321-8843; ISSN(P): 2347-4599 Vol. 2, Issue 7, Jul 2014, 113-122 © Impact Journals FUTURE OF AN OASIS TO THE DETRIMENT OF A HYDRAULIC MONUMENT “CASE OF TIMIMOUN” RATIBA WIDED BIARA 1 & DJAMAL ALKAMA 2 1Department of Architecture, Faculty of Science & Technology, Bechar University, Béchar, Algeria 2Department of Architecture, Mohamed Khider University, Biskra, Algeria ABSTRACT "Foggara" certainly reflects a system of conventional irrigation, which has long served as caravan dwellers and roaming in their travels through the Sahara. But, it reports ingenious irrigation process conjecture, is adapting to the climate, inherent social context to this region. It’s a method for groundwater capture who assured the payment of local institutions in the Algerian Sahara. History testified to an evolution of the oasis, where the parties y related to abandoned, while others replaced the percolates gardens. Causes emanate from the drawdown of the sheet, either to silting, or at the same time. There are overriding reasons that justify the occupation of the ground of human settlements in the Gourara. If the foggara, has of sustainability for long periods the Algerian oasis; It is also important to mention that the hydraulic evolution, which were subject, has been proven in the Gourara: typically at Timmoun. Unfortunately today we are witnessing the decline of countless oasis of foggara. Thus, it can be assumed a quasi interim implementation in the Gourara; even can be downright fear further severe natural conditions, final desertification in the region. In view of this is to ask: How can we preserve and safeguard this hydraulic heritage? KEYWORDS: Foggara, Hydraulic Monument, Decline, Heritage Approach to Backup, Timmoun/Gourara INTRODUCTION This is the Algerian Sahara, a vast area, which is divided, if it is by nature itself, then by men, in three parts: The Gourara region, the Touat, and the Tidikelt.