A Selfish Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

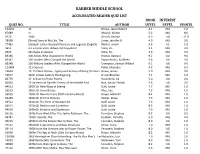

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Coach's Word Packets©

! ! Coach’s Word Packets © ! 1. Level 1-100 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “A Bus Trip to the River” ! 2. Level 101-200 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “Two Houses” ! 3. Level 201-300 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “A Trip to the Country” ! 4. Level 301-400 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “My School Day” ! 5. Level 401-500 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “The Good Book” ! ! ©copyright 2014 ! ! ! !2 The New First 100 Fry Words in Phrases ! 1. The people 28. We had their dog 2. of the water 29. By the river water 3. Now and then 30.The first words 4. This is a good day. 31. But not for me 5. From here to there 32. Not him or her 6. up in the air 33. What will they do? 7. Now is the time 34. All or some 8. Can you see? 35. We were 9. That dog is 36. We like to write 10. He has it. 37. When will we 11. He called me. 38. Write your 12. There was 39. Can he 13. for some people 40. She said to go 14. on the bus. 41. So there you are 15. How long are 42. No use 16. as big as the first 43. An angry cat 17. with his mother 44. Each of us 18. for his people 45. Which way 19. What did they say 46. She sat 20. I like him. 47. Do you 21. at your house 48. How did they 22. -

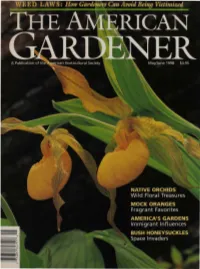

Willi Orchids

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

A B S T R a C T S

5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting Perspectives on an endangered species A B S T R A C T S EGSM 5 • 5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting • Rust •Austria • 02-05 Oct 2014 • egsm2014.univie.ac.at EGSM 5 5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting Perspectives on an endangered species ABSTRACTS 02‐05 October 2014 • Rust • Burgenland • Austria 5th European Ground Squirrel Meeting Perspectives on an endangered species Published and edited by: Eva Millesi and Ilse E. Hoffmann Department of Behavioural Biology Faculty of Life Sciences University of Vienna, Althanstraße 14 1090 Vienna, Austria http://www.behaviour.univie.ac.at/ The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from them remain the responsibility of the authors. Revision of abstracts: Ilse E. Hoffmann, Werner Haberl Layout: Dagmar Rotter, Ilse E. Hoffmann, Michaela Brenner Cover: Ilse E. Hoffmann Photograph © Lukas Mroz / modified after maps.iucnredlist.org (http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=20472/) Printed by: druck.at, Aredstraße 7, 2544 Leobersdorf, Austria Printed with the support of: Amt der NÖ Landesregierung, Abteilung Naturschutz (RU5) ISBN 978-3-200-03792-2 © 2014 University of Vienna Contents Preface ............................................................................... 1 Behavioural Ecology ................................................................ 3 Seasonal shift in the diet of the European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus) in Hungarian dry grasslands B. GYŐRI-KOÓSZ, K. KATONA and S. FARAGÓ ..................................... 5 Relations between genetic, geographic and acoustic distances in five populations of speckled ground squirrels Spermophilus suslicus V.A. MATROSOVA, L.E. SAVINETSKAYA, O.N. SHEKAROVA, S.V. PROYAVKA (PIVANOVA), M.Yu. RUSIN, A.V. RASHEVSKA, I.A. VOLODIN, E.V. VOLODINA and A.V. TCHABOVSKY ................................................................ 6 Ontogeny of the alarm call in the European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus): findings from a semi-natural enclosure I. -

Show #1276 --- Week of 6/24/19-6/30/19

Show #1276 --- Week of 6/24/19-6/30/19 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL________________ SEGMENT ONE: "Million Dollar Intro" - Ani DiFranco :55 in-studio n/a "The Luckiest"-Ben Folds 4:20 Rockin’ The Suburbs Epic "Atlantic"-Kelsey Lu 3:10 Blood Columbia "Hard Way"-Jamestown Revival 3:15 San Isabel Thirty Tigers "Hardwired"-Hailey Knox (in-studio) 3:25 in-studio n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** New West Records/Buddy & Julie Miller "Breakdown On 20th Ave. South" (:30) Outcue: " at NewWestRecords.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 16:52 ***PLAY CUSTOMIZED STATION ID INTO: SEGMENT TWO: "Turn Off The News (Build A Garden)"-Promise Of The Real 3:00 Turn Off The News (Build A Garden) Fantasy ***INTERVIEW & MUSIC: RODRIGO y GABRIELA ("Kratona Days," "Electric Soul") in-studio interview/performance n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** The Ark/"Monthly Schedule" (:30) Outcue: " TheArk.org." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 20:00 SEGMENT THREE: "Weak Wrists"-Elissa LeLeCoque (Song.Writer podcast) 3:30 Perspective self-released "Heavy On My Mind"-Mavis Staples 3:40 We Get By Anti- "Pull You Close"-JR JR 3:55 Invocations/Conversations Love Is EZ "Walter Reed"-Michael Penn (in-studio) 3:40 in-studio n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Leon Speakers/"The Leon Loft" (:30) Outcue: " at LeonSpeakers.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 18:08 TOTAL TIME FOR HOUR ONE-55:00 acoustic café · p.o. box 7730 · ann arbor, mi 48107-7730 · 734/761-2043 · fax 734/761-4412 [email protected] ACOUSTIC CAFE, CONTINUED Page 2 Show -

View Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 – November 22, 2017) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. -

RODERICK MAIN Revelations of Chance SUNY Series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology

REVELATIONS OF C HANCE Synchronicity as Spiritual Experience RODERICK MAIN Revelations of Chance SUNY series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology Richard D. Mann, editor Revelations of Chance Synchronicity as Spiritual Experience Roderick Main State University of New York Press Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2007 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 194 Washington Avenue, Suite 305, Albany NY 12210-2384 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Anne M. Valentine Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Main, Roderick. Revelations of chance : synchronicity as spiritual experience / Roderick Main. p. cm. — (SUNY series in transpersonal and humanistic psychology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-7023-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-7024-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Coincidence—Religious aspects. I. Title. II. Series. BL625.93.M35 2007 204'.2—dc22 2006012813 10987654321 In memory of John Mein Main (1930–2006) CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Synchronicity and Spirit 11 3. The Spiritual Dimension of Spontaneous Synchronicities 39 4. Symbol, Myth, and Synchronicity: The Birth of Athena 63 5. Multiple Synchronicities of a Chess Grandmaster 81 6. -

Civil War Era Correspondence Collection

Civil War Era Correspondence Collection Processed by Curtis White – Fall 1994 Reprocessed by Rachel Thompson – Fall 2010 Table of Contents Collection Information Volume of Collection: Two Boxes Collection Dates: Restrictions: Reproduction Rights: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History Location: Archives Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Biographical Sketches Anonymous: This folder consists of one photocopy of a letter from an unknown soldier to “Sallie” about preparations for the Battle of Allegheny Mountain, Virginia (now West Virginia). Anonymous [J.A.R?]: This folder contains the original and enlarged and darkened copies of a letter describing to the author’s sister his sister the hardships of marching long distances, weather, and sickness. Reuben M. Benjamin was born in June 1833 in New York. He married Laura W. Woodman in 1857. By 1860, they were residents of Bloomington, IL. Benjamin was an attorney and was active in the 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention. Later, he became an attorney in the lead Granger case of Munn vs. the People which granted the states the right to regulate warehouse and railroad charges. In 1873, he was elected judge in McLean County and helped form the Illinois Wesleyan University law school. His file consists of a transcript of a letter to his wife written from La Grange, TN, dated January 21, 1865. He may have been part of a supply train regiment bringing food and other necessities to Union troops in Memphis, TN. This letter mentions troop movements. Due to poor health, Benjamin served only a few months. -

The Inheritance

The Inheritance EDWARD (TED) TODD, 2012 The Inheritance This is Autobiofiction .............................................................................................................. 4 BookEsalen 1. Institute The Father of Human .................................................................................................... Relations, California 1979 ............................................... 17 5 Near the Don River, Russia 1945 ................................................................................... 17 Russians ................................................................................................................................22 The Journey 1957 .................................................................................................................. 35 Uncle Carlos, Argentina 1958 ........................................................................................... 59 Antonio Garibaldi, Buenos Aires, a few months later ............................................. 67 BookOscar 2.1976 The ............................................................................................................................... Son’s Story ........................................................................................... 8270 Budapest 1980 ....................................................................................................................... 88 INTERLUDE:The other Grandma Is Life Really is crazy? a Jewish .................................................................................... -

Bill Harry. "The Paul Mccartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970

Bill Harry. "The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970 BILL HARRY. THE PAUL MCCARTNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA Tadpoles A single by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, produced by Paul and issued in Britain on Friday 1 August 1969 on Liberty LBS 83257, with 'I'm The Urban Spaceman' on the flip. Take It Away (promotional film) The filming of the promotional video for 'Take It Away' took place at EMI's Elstree Studios in Boreham Wood and was directed by John MacKenzie. Six hundred members of the Wings Fun Club were invited along as a live audience to the filming, which took place on Wednesday 23 June 1982. The band comprised Paul on bass, Eric Stewart on lead, George Martin on electric piano, Ringo and Steve Gadd on drums, Linda on tambourine and the horn section from the Q Tips. In between the various takes of 'Take It Away' Paul and his band played several numbers to entertain the audience, including 'Lucille', 'Bo Diddley', 'Peggy Sue', 'Send Me Some Lovin", 'Twenty Flight Rock', 'Cut Across Shorty', 'Reeling And Rocking', 'Searching' and 'Hallelujah I Love Her So'. The promotional film made its debut on Top Of The Pops on Thursday 15 July 1982. Take It Away (single) A single by Paul which was issued in Britain on Parlophone 6056 on Monday 21 June 1982 where it reached No. 14 in the charts and in America on Columbia 18-02018 on Saturday 3 July 1982 where it reached No. 10 in the charts. 'I'll Give You A Ring' was on the flip.