Feminism, Identity, and Gender in Angela Carter's The Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter's Nights

INFOKARA RESEARCH ISSN NO: 1021-9056 Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus R.Padhmavathi Ph.D Researchscholar Department of English Email id:[email protected] AnnamalaiUniversity ,Chidhambaram. Dr.A.Glory , Asst.professor, Department of English Annamalai University, Chidhambaram Abstract: This paper endeavors to examine critically and analytically how the Marxist feminism is developed in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus (1984), and how the postmodernistic ideas in her mind. It sheds light on the feminine themes and concerns, and in this novel Angela Carter speaks out lots of feminine matters and moves around strongly in her mind. Her lasting fascination with femininity as vision has until then been understood mainly in terms of a feminist critical project which identifies and rejects male-constructed images of women as a form of false consciousness. Keywords: Feminism, Marxism, Carnivalisation, Postmodernism Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter’s Nights At The Circus Angela Carter’s achievements asa feminist are clearly understood only if we look at her novels with postmodern eyes. Her novels make no sense unless they are given a postmodern reading which can extricate the challenging thoughts on the essence of womanhood that lie entangled in fantasies, dreams, myths, and parodies. Through reading the novels of Angela Carter, it is noticeable that she goes in the femininity track in her fictional writings. HerNights at the Circus is a novel about the ways in which these dominant, frequently male-centered discourses of power marginalize those whom society defines as freaks, madmen, clowns, the physically and mentally deformed, and, in particular, women, so that they may be contained and controlled because they are all possible sources of the disordered disruption of established power. -

The Quest for Female Empowerment in Angela Carter's Wise Children

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN Supervisor: Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of Professor Marysa Demoor the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Aline Lapeire 2009-2010 Lapeire ii Lapeire iii “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN The cover of Wise Children (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007) Lapeire iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the help of the following people. I would hereby like to thank… … Professor MARYSA DEMOOR for supporting my choice of topic and sharing her knowledge about gender studies. Her guidance and encouragement have been very important to me. … DEBORA VAN DURME and Professor SINEAD MCDERMOTT for their interesting class discussions of Nights at the Circus and Wise Children. Without their keen eye for good fiction, I might have never even heard of Angela Carter and her beautiful oeuvre. … Several very patient librarians at the University of Ghent. … A great deal of friends who at times mocked the idea of a „gender dissertation‟, yet always showed their support when it was due. I especially want to thank my loyal thesis buddies MAX DEDULLE and MARTIJN DENTANT. The countless hours we spent together while hopelessly staring at a world behind the computer screen eventually did pay off. Moreover, eternal gratitude and a vodka-Red Bull go out to JEROEN MEULEMAN who entirely voluntarily offered to read and correct my thesis. -

The Consumption of Angela Carter

The Consumption of Angela Carter: Women, Toody and Power EMMA PARKER A great writer and a great critic, V. S. Pritchett, used to sav that he swallowed Dickens whole, at the risk of indigestion. I swallow Angela Carter whole, and then I rush to buy Alka Seltzer. The "minimalist" nouvelle cuisine alone cannot satisfy my appetite for fiction. I need a "maximalist" writer who tries to tell us many things, with grandiose happenings to amuse me, extreme emotions to stir my feelings, glorious obscenities to scandalise me, brilliant and malicious expressions to astonish me. (Almansi 217) L Vs GUIDO ALMANSI suggests, consuming Angela Carter's fic• tion is simultaneously satisfying and unsettling. This is partly because, as Hermione Lee has commented, Carter "was always in revolt against the 'tyranny of good taste'" (316). As a cham• pion of moral pornography, a cultural dissident who dared to disparage Shakespeare, and a culinary iconoclast who criticised the highly-esteemed cookery writer Elizabeth David, Carter out• raged many people. Yet this impiety also gives her work its ap• peal.1 Like the critical essays, her fiction is deliciously "improper" in that it interrogates and rejects what Hélène Cixous calls the realm of the proper, a masculine economy based on the principles of authority, domination and owner• ship — a realm in which, disempowered and dispossessed, women are without property ("Castration" 42, 50). Her fiction has an unsettling effect precisely because Carter seeks to "up• set" the patriarchal order, in part through her representation of consumption, which, by revealing and refiguring the relation• ship between women, food, and power, challenges the struc• tures that underpin patriarchy. -

Identity I N Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children

Performing (and) Identity In Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children Janine Root @ B .A. B. Ed A cnesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Lakehead University, Thnder Bay, Ontario, 1999 National Library BibliotMy nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Cana a Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wauinglm Strwt 385. rue WdlingWn WONK1AW o(I.waON K1AW Cwudr CMed. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Libmy of Cana& to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, prster, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imprimes reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. Abstract In her last two novels, Nights at the Circus and Wise Children, Angela Carter examines some of the complex factors involved in the construction of identity, both within the fictional world, and for readers in their interaction with 'Le .jn-74 ,., I ,,,, 2f the fictix. 35 zhese f3ctxs, qezier is cf primary importance. -

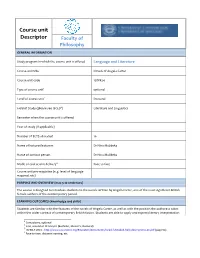

Course Unit Descriptor

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered Language and Literature Course unit title Novels of Angela Carter Course unit code 15DFk24 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Doctoral Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 10 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Angela Carter, one of the most significant British female authors of the contemporary period. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Angela Carter, as well as with the position the authoress takes within the wider context of contemporary British fiction. Students are able to apply and express literary interpretation 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. effectively. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Angela Carter, contemporary British novel, feminist theory and engaged writing. Shadow Dance as parodic contemporary gothic fiction. Let’s begin countering patriarchal stereotypes: The Magic Toyshop. Several Perceptions: generation gap and the counterculture of the 60s. -

Section A. Feminist Theory in Late-Nineteenth-Century France, The

45 2 Section A. Feminist Theory In late-nineteenth-century France, the word féminisme, meaning women’s liberation was first used in political debates. The most generic way to define feminism is to say that it is an organized activity on behalf of women’s rights and common interests and based on the theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes. Some initial forms of feminism were criticized for considering the perspective of only white, middle-class and educated people. Ethnically specific or multiculturalists forms of feminism were created as a reaction to this criticism. Most feminists believe that inequality between men and women are open to change because they are socially constructed. Many consider feminism as theory or theories, but some others see it as merely a kind of politics in the culture. Feminist theory aims to understand gender inequality and focus on sexuality, gender politics, and power relations. To achieve this, it has developed theories in a wide range of disciplines. Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into fields of theory or philosophy. Since in academic institutions ‘theory’ is often the male standpoint and feminists have fought hard to expose the fraudulent objectivity of male ‘science’, (for example, the Freudian theory of female sexual development) some feminists have not wished to embrace theory at all. Raman Selden, Widdowson and Brooker argue “Feminism and feminist criticism may be better termed a cultural politics than a theory or theories” (116). However, much recent feminist criticism wants to free itself from the ‘fixities and definites’ of theory and to develop a female discourse which is not considered as a belonging to a recognized conceptual position (and, therefore, probably male produced). -

Modernism and Postmodernism in Feminism: a Conceptual Study on the Developments of Its Defination, Waves and School of Thought

1 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), Volume 4, Issue 1, (page 1 - 14), 2019 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH) Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2019 e-ISSN : 2504-8562 Journal home page: www.msocialsciences.com Modernism and Postmodernism in Feminism: A Conceptual Study on the Developments of its Defination, Waves and School of Thought Mohd Hafiz Bin Abdul Karim1, Ariff Aizuddin Azlan2 1Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC-IIUM) 2Faculty of Administrative Science and Policy Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Correspondence: Mohd Hafiz Bin Abdul Karim ([email protected]) Abstract ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ This study seeks to identify the relations of modernism and postmodernism in feminism by looking deeply on the development of its definitions, waves of feminism and framework in its specific schools of thought; liberal, classical Marxist, socialist and radical feminism. By adapting qualitative descriptive study, this study covers mainly secondary data from English language sources, be it from books, academic articles or any literatures pertaining to this topic, which obtained from various databases. This study argues that modernism and postmodernism is the worldviews that become the essence of feminism. By looking at the variations of how feminism is studied, e.g. definitions, waves and school of thought, this study concluded that there are several points indicating the relations that exist between modernism and postmodernism with feminism. Modernism can be seen in the relational approach of the liberal, classical Marxist and socialist feminism in the first wave, which are more centered on education, politics and economic participation. Meanwhile, the relation of postmodernism to feminism is exampled in the deconstructing approach of the radical feminism that began from the second wave shown in their individualist views on sex, sexuality, motherhood, childbirth, and language institution. -

Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus: a Feminist Spatial Journey to Emancipation and Gender Justice

International Review of Literary Studies IRLS 2 (2) December 2020 ISSN: Online 2709-7021; Print 2709-7013 Angela Carter’s Nights at The Circus: A Feminist Spatial Journey to Emancipation and Gender Justice Dr. Wiem Krifa1 International Review of Literary Studies Vol. 2, No. 2; December 2020, pp. 46- 61 Published by: MARS Research Forum Received: October 10, 2020 Accepted: December 15, 2020 Published: December 22, 2020 Abstract Mobility can be considered as a natural characteristic of human beings, regardless of gender, sex or geographical roots. Within the feminist postmodern context, mobility ushers women in a new world based on gender equality and tolerance. Angela Carter’s Nights at The Circus displays a female character who achieves her New Woman status while traveling from one country to another, as a circus aerialist. Fevvers’ train journey from London to Siberia, together with her lover, empowers her female being. Space proves to be a substantial prerequisite for the achievement of the human subjectivity whether the female or the masculine one. Carter’s heroine succeeds to overcome the patriarchal misogynist attitude that surrounds her professional career and ends by achieving her female subjectivity. Besides, she triumphs to metamorphose Walser from the traditional male figure who looks to debunk Fevvers ‘claimed bird origin, into the new postmodern man who believes in gender equality and surrenders to Fevvers’love. All along their journey, Fevvers, Walser and other female characters, undergo a deep transformation at the level of their personal growth and subjectivities. They overcome their culturally internalized believes, to be prepared for a life based on equal principles and free from the imposed patriarchal cultural constraints. -

Egoism and the Post-Anarchic: Max Stirner's New Individualism

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY SAN MARCOS THESLS SIGNATURE PAGE Tl IESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF Tl IE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS IN LITERA TUR.E AND WRITING STUDIES THESIS TJTLE: Egoism and the Post-Anarchic: Max Stimer's New Individualism AUTHOR: Kristian Pr'Out DATE OF SUCCESSFUL DEFEN E: May 911' 2019 --- THE THESIS HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE THESIS COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LITERATURE AND WRITING STUDIES. Oliver Berghof August 5, 2019 TIIESIS COMMITTEE CHAIR DATE Francesco Levato 8/5/19 TIIESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER DATE Heidi Breuer �-11 THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER DATE Pr’Out 1 Egoism and the Post-Anarchic: Max Stirner’s New Individualism Kristian Pr’Out Pr’Out 2 Table of Contents Preface 3 Chapter 1 Max Stirner: Biographers and Interpreters 13 Stirner and The Dialectic: A Genealogy of Liberalism 23 Fichte and the Unique One: Speaking the Intangible 32 Chapter 2 Stirner and the Case for Anarchism 39 Stirner’s Egoism Meets Classical Anarchism 48 Welsh’s Dialectical Egoism and Post-Anarchist Individualism 64 Chapter 3 May 1968 and Its Impact 67 Post-Anarchism: A Contemporary Theoretical Model 82 Narrative and the Critique of Modernity 89 ‘Ownness,’ Power, and The Material 92 Conclusion: A Revenant Returns 102 Bibliography 104 Pr’Out 3 Preface In the 19th century, the influence of Georg W. F. Hegel was widespread. His works influenced anarchists, communists, the moderately liberal, and the staunchly traditional. In Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1977), history operates in certain movements - namely, that of a world spirit that ushers in new and different epochs (6-7). -

Beyond Postmodern Margins: Theorizing Postfeminist Consequences Through Popular Female Representation

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Beyond Postmodern Margins: Theorizing Postfeminist Consequences Through Popular Female Representation Victoria Mosher University of Central Florida Part of the Women's Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mosher, Victoria, "Beyond Postmodern Margins: Theorizing Postfeminist Consequences Through Popular Female Representation" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3605. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3605 BEYOND POSTMODERN MARGINS: THEORIZING POSTFEMINIST CONSEQUENCES THROUGH POPULAR FEMALE REPRESENTATION by VICTORIA MOSHER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ©2008 Victoria Mosher iii ABSTRACT In 1988, Linda Nicholson and Nancy Fraser published an article entitled “Social Criticism Without Philosophy: An Encounter Between Feminism and Postmodernism,” arguing that this essay would provide a jumping point for discussion between feminisms and postmodernisms within academia. Within this essay, Nicholson and Fraser largely disavow a number of second wave feminist theories due to their essentialist and foundationalist underpinnings in favor of a set of postmodernist frameworks that might help feminist theorists overcome these epistemological impediments. -

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title/Author Publisher Year ISBN Annotations 5638 1000-year-old boy, The HarperCollins 2018 9780008256944 Alfie Monk is like any other pre-teen, except he's 1000 years old and Welford, Ross Children's Books can remember when Vikings invaded his village and he and his family had to run for their lives. When he loses everything he loves in a tragic fire and the modern world finally catches up with him, Alfie embarks on a mission to change everything by finally trusting Aidan and Roxy enough to share his story, and enlisting their help to find a way to, eventually, make sure he will eventually die. 22034 13 days of midnight Orchard Books 2015 9781408337462 Luke Manchett is 16 years old with a place on the rugby team and the Hunt, Leo prettiest girl in Year 11 in his sights. Then his estranged father suddenly dies and he finds out that he is to inherit six million dollars! But if he wants the cash, he must accept the Host. A collection of malignant ghosts who his Necromancer father had trapped and enslaved! Now the Host is angry, the Host is strong, and the Host is out for revenge! Has Luke got what it takes to fight these horrifying spirits and save himself and his world? 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Scholastic Australia 2018 9781742998381 Tick and his friends are still trying to work out how to defeat Mistress Dashner, James Jane, but when there are 13 realities from which to draw trouble, the battle is 13 times as hard. -

Gendered Landscapes Project”

CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 5 Preamble 5 Section 1 Gender and geographical landscape 9 Introduction 8 Defining “landscape” 13 Three feminist approaches to gender and landscape 19 A liberal feminist approach 20 A radical/socialist feminist approach 25 A postmodern feminist approach 34 Section 2 Case study on Hill End 40 Introduction 40 A brief introduction to Hill End, as if women mattered 41 Feminist interpretations of landscape imagery in Hill End 51 Conclusions 70 Section 3 Summary and recommendations 72 Summary 72 List of references 74 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report offers a literature review as the initial step in the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) Cultural Heritage Division’s “Gendered Landscapes Project”. It outlines some of the possibilities of such a project within the context of this state government agency by presenting an overview of research in the topic area, with an emphasis on studies of national parks and women. It also offers a case study examining gender and landscape in historical and art images associated with the NPWS “Historic Site” township of Hill End. The report proposes, from a social constructivist perspective, that “landscape” is a spatial representation of human relationships with nature, while “gender” is the representation of sexual difference, and that both concepts are malleable, cultural constructions. However, in agreement with Kay Schaffer’s Women and the Bush (1988), the report argues that in Australia two dominant historic modes of gendering the landscape have been to represent it firstly as the site of white masculine endeavour (“no place for a woman”) and secondly as a feminine being (“Mother Nature”).