Stock-Flow Analysis in Consumption and Household Production Theory : a Review and Synthesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theory of Household Behavior: Some Foundations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, Volume 4, number 1 Volume Author/Editor: Sanford V. Berg, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/aesm75-1 Publication Date: 1975 Chapter Title: The Theory of Household Behavior: Some Foundations Chapter Author: Kelvin Lancaster Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10216 Chapter pages in book: (p. 5 - 21) Annals a! E won;ic and Ss to!fea.t ure,twn t, 4 1975 THE THEORY OF IIOUSEIIOLI) BEHAVIOR: SOME FOUNDATIONS wt' K1LVIN LANCASTER* This paper is concerned with examining the common practice of considering the household to act us if it were a single individuaL Iconcludes rhut aggregate household behavior wifl diverge front the behavior of the typical individual in Iwo important respects, but that the degree of this divergence depend: on well-defined variables--the number of goods and characteristics in the consu;npf ion fecIJflolOgv relative to the size of the household, and thextent of joint consumption within the houseiwid. For appropriate values of these, the degree of divergence may be very small or zero. For some years now, it has been common to refer to the basic decision-making entity with respect to consumption as the "household" by those primarily con- cerned with data collection and analysis and those working mainly with macro- economic models, and as the "individua1' by those working in microeconomic theory and welfare economics. Although one-person households do exist, they are the exception rather than the rule, and the individual and the household cannot be taken to be identical. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

1 John Stuart Mill Selections from on the Subjection of Women John

1 John Stuart Mill Selections from On the Subjection of Women John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was an English philosopher, economist, and essayist. He was raised in strict accord with utilitarian principles by his economist father James Mill, the founder of utilitarian philosophy. John Stuart recorded his early training and subsequent near breakdown in in his Autobiography (“A Crisis in My Mental History. One Stage Onward”), published after his death by his step-daughter, Helen Taylor, in 1873. His strictly intellectual training led to an early crisis which, as he records in this chapter, was only relieved by reading the poetry of William Wordsworth. During his life, Mill published a number of works on economic and political issues, including the Principles of Political Economy (1848), Utilitarianism (1863), and On Liberty (1859). After his death, besides the Autobiography, his step-daughter published Three Essays on Religion in 1874. On the Subjection of Women (1869) is Mill’s utilitarian argument for the complete equality of women with men. Scholars think that it was greatly influenced by Mill’s discussions with Harriet Taylor, whom Mill married in 1851. The essay is addressed to men, the rulers and controllers of nineteenth-century society, and is his contribution to what had become known as “the woman question,” that is, what liberties should be accorded to women in society. As such, it is a clear and still-relevant contribution to the ongoing discussion of women’s rights and their desire to achieve what Mill announces in his opening thesis, “perfect equality.” Information readily available on the internet has not been glossed. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

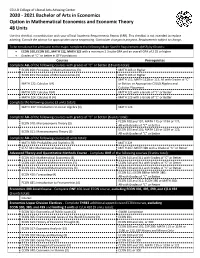

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Household Income and Wealth

HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND WEALTH INCOME AND SAVINGS NATIONAL INCOME PER CAPITA HOUSEHOLD DISPOSABLE INCOME HOUSEHOLD SAVINGS INCOME INEQUALITY AND POVERTY INCOME INEQUALITY POVERTY RATES AND GAPS HOUSEHOLD WEALTH HOUSEHOLD FINANCIAL ASSETS HOUSEHOLD DEBT NON-FINANCIAL ASSETS BY HOUSEHOLDS HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND WEALTH • INCOME AND SAVINGS NATIONAL INCOME PER CAPITA While per capita gross domestic product is the indicator property income may never actually be returned to the most commonly used to compare income levels, two country but instead add to foreign direct investment. other measures are preferred, at least in theory, by many analysts. These are per capita Gross National Income Comparability (GNI) and Net National Income (NNI). Whereas GDP refers All countries compile data according to the 1993 SNA to the income generated by production activities on the “System of National Accounts, 1993” with the exception economic territory of the country, GNI measures the of Australia where data are compiled according to the income generated by the residents of a country, whether new 2008 SNA. It’s important to note however that earned on the domestic territory or abroad. differences between the 2008 SNA and the 1993 SNA do not have a significant impact of the comparability of the Definition indicators presented here and this implies that data are GNI is defined as GDP plus receipts from abroad less highly comparable across countries. payments to abroad of wages and salaries and of However, there are practical difficulties in the property income plus net taxes and subsidies receivable measurement both of international flows of wages and from abroad. NNI is equal to GNI net of depreciation. -

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: The Keynes Effect D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA USA [email protected] Version 1.3 September 2009 15,246 Words This paper was initially presented at The First International Symposium on the History of Economic Thought “The Integration of Micro and Macroeconomics from a Historical Perspective,” University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, August 3-5, 2009. Abstract: Two popular claims about mid-to-late twentieth century economics are that Walrasian ideas had a significant impact on the Keynesian macroeconomics that became dominant during the 1950s and 1060s, and that Arrow-Debreu Walrasian general equilibrium theory passed its zenith in microeconomics at some point during the 1980s. This paper does not challenge either of these standard interpretations of the history of modern economics. What the paper argues is that there are at least two very important relationships between Keynesian economics and Walrasian general equilibrium theory that have not generally been recognized within the literature. The first is that influence ran not only from Walrasian theory to Keynesian, but also from Keynesian theory to Walrasian. It was during the neoclassical synthesis that Walrasian economics emerged as the dominant form of microeconomics and I argue that its compatibility with Keynesian theory influenced certain aspects of its theoretical content and also contributed to its success. The second claim is that not only did Keynesian economics contribute to the rise Walrasian general equilibrium theory, it has also contributed to its decline during the last few decades. The features of Walrasian theory that are often suggested as its main failures – stability analysis and the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems on aggregate excess demand functions – can be traced directly to the features of the Walrasian model that connected it so neatly to Keynesian macroeconomics during the 1950s. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Monetary Policy in the New Neoclassical Synthesis: a Primer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Monetary Policy in the New Neoclassical Synthesis: A Primer Marvin Goodfriend reat progress was made in the theory of monetary policy in the last quarter century. Theory advanced on both the classical and the Keynesian sides. New classical economists emphasized the G 1 importance of intertemporal optimization and rational expectations. Real business cycle (RBC) theorists explored the role of productivity shocks in models where monetary policy has relatively little effect on employment and output.2 Keynesian economists emphasized the role of monopolistic competition, markups, and costly price adjustment in models where mon- etary policy is central to macroeconomic fluctuations.3 The new neoclas- sical synthesis (NNS) incorporates elements from both the classical and the Keynesian perspectives into a single framework.4 This “primer” provides an in- troduction to the benchmark NNS macromodel and its recommendations for monetary policy. The author is Senior Vice President and Policy Advisor. This article origi- nally appeared in International Finance (Summer 2002, 165–191) and is reprinted in its entirety with the kind permission of Blackwell Publishing [http://www.blackwell- synergy.com/rd.asp?code=infi&goto=journal]. The article was prepared for a conference, “Stabi- lizing the Economy: What Roles for Fiscal and Monetary Policy?” at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, July 2002. The author thanks Al Broaddus, Huberto Ennis, Mark Gertler, Robert Hetzel, Andreas Hornstein, Bennett McCallum, Adam Posen, and Paul Romer for valuable comments. Thanks are also due to students at the GSB University of Chicago, the GSB Stanford University, and the University of Virginia who saw earlier versions of this work and helped to improve the exposition. -

Econ5153 Mathematical Economics

ECON5153 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS University of Oklahoma, Fall 2014 Tuesday and Thursday, 9-10:15am, Cate Center CCD1 338 Instructor: Qihong Liu Office: CCD1 426 Phone: 325-5846 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:30-2:30pm, and by appointment Course Description This is the first course in the graduate Mathematical Economics/Econometrics sequence. The objective of this course is to acquaint the students with the fundamental mathematical techniques used in modern economics, including Matrix Algebra, Optimization and Dynam- ics. Upon completion of the course students will be able to set up and analytically solve constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. The students will also be able to solve linear difference equations and differential equations. Textbooks Required: Simon and Blume: Mathematics for Economists, W.W.Norton, 1994. Other useful books available on reserve at Bizzell: Chiang and Wainwright: Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, Fourth Edition, 2005. Darrell A. Turkington: Mathematical Tools for Economics, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Avinash Dixit: Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1990. Michael D. Intriligator: Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory, Prentice-Hall, 1971. Assessment Grades are based on homework (15%), class participation (10%), two midterm exams (20% each) and final exam (35%). You are encouraged to form study groups to discuss homework and lecture materials. All exams will be in closed-book forms. Problem Sets Several problem sets will be assigned during the semester. You will have at least one week to complete each assignment. Late homework will not be accepted. You are allowed to work 1 with other students in this class on the problem sets, but each student must write his or her own answers. -

Paul Samuelson's Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boianovsky, Mauro Working Paper Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Boianovsky, Mauro (2019) : Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196831 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Paul Samuelson’s Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics by Mauro Boianovsky CHOPE Working Paper No. 2019-08 May 2019 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3386201 1 Paul Samuelson’s ways to macroeconomic dynamics Mauro Boianovsky (Universidade de Brasilia) [email protected] First preliminary draft. -

Mathematical Economics

ECONOMICS 113: Mathematical Economics Fall 2016 Basic information Lectures Tu/Th 14:00-15:20 PCYNH 120 Instructor Prof. Alexis Akira Toda Office hours Tu/Th 13:00-14:00, ECON 211 Email [email protected] Webpage https://sites.google.com/site/aatoda111/ (Go to Teaching ! Mathematical Economics) TA Miles Berg, Econ 128, [email protected] (Office hours: TBD) Course description Carl Friedrich Gauss said mathematics is the queen of the sciences (and number theory is the queen of mathematics).1 Paul Samuelson said economics is the queen of the social sciences.2 Not surprisingly, modern economics is a highly mathematical subject. Mathematical economics studies the mathematical foundations of economic theory in the approach known as the Arrow-Debreu model of general equilibrium. Partial equilibrium (things like demand and supply curves), which you have probably learned in Econ 100ABC, considers each market separately. General equilibrium (GE for short), on the other hand, considers the economy as a whole, taking into account the interaction of all markets. Econ 113 is probably the most mathematically advanced undergraduate course of- fered at UCSD Economics, but it should have a high return. In the course, we will develop a mathematical model of classical economic thoughts like Bentham's \greatest happiness principle" and Smith's \invisible hand", and prove theorems. Then we will apply the theory to international trade, finance, social security, etc. Time permitting, I will talk about my own research. Prerequisites A year of calculus and a year of upper division microeconomic theory (at UCSD these courses are Math 20ABC and Economics 100ABC) are required.