On the Rising Complexity of Bank Regulatory Capital Requirements: from Global Guidelines to Their United States (US) Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Extent to Which Financial Crises Are Occasional and the Role of Collateralised Derivatives in the Global Financial Crisis

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: C Finance Volume 17 Issue 2 Version 1.0 Year 2017 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 The Extent to Which Financial Crises Are Occasional and the Role of Collateralised Derivatives in the Global Financial Crisis By Stanyo Dinov Abstract- The article aims to explore to which extent financial crises occur periodically and under what particular conditions, or whether they are occasional and unpredictable. By recalling some of the financial crises from the last century, using historic and systematic approach of investigation the article analyses the factors and the events which stimulate a financial crisis. Particular attention is pointed at the last global financial crisis and one of its reasons, namely the collateralisation of the derivatives of mortgage loans on the US property market. In this regard, different factors are compared, such as the partabolishment of the Brett on Woods agreement and its replacement with a floating currency system, the development of new innovative financial products, the deregulation of the financial markets and the increase of debt in the private sector. The work examines common patterns stimulating financial crises and at the end gives answers to what extend financial crises can be predictable. GJMBR-C Classification: JEL Code: F65 TheExtenttoWhichFinancialCrisesAreOccasionalandtheRoleofCollateralisedDerivativesintheGlobalFinancialCrisis Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2017. Stanyo Dinov. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

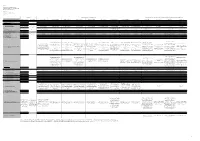

Basel III: Post-Crisis Reforms

Basel III: Post-Crisis Reforms Implementation Timeline Focus: Capital Definitions, Capital Focus: Capital Requirements Buffers and Liquidity Requirements Basel lll 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 2027 1 January 2022 Full implementation of: 1. Revised standardised approach for credit risk; 2. Revised IRB framework; 1 January 3. Revised CVA framework; 1 January 1 January 1 January 1 January 1 January 2018 4. Revised operational risk framework; 2027 5. Revised market risk framework (Fundamental Review of 2023 2024 2025 2026 Full implementation of Leverage Trading Book); and Output 6. Leverage Ratio (revised exposure definition). Output Output Output Output Ratio (Existing exposure floor: Transitional implementation floor: 55% floor: 60% floor: 65% floor: 70% definition) Output floor: 50% 72.5% Capital Ratios 0% - 2.5% 0% - 2.5% Countercyclical 0% - 2.5% 2.5% Buffer 2.5% Conservation 2.5% Buffer 8% 6% Minimum Capital 4.5% Requirement Core Equity Tier 1 (CET 1) Tier 1 (T1) Total Capital (Tier 1 + Tier 2) Standardised Approach for Credit Risk New Categories of Revisions to the Existing Standardised Approach Exposures • Exposures to Banks • Exposure to Covered Bonds Bank exposures will be risk-weighted based on either the External Credit Risk Assessment Approach (ECRA) or Standardised Credit Risk Rated covered bonds will be risk Assessment Approach (SCRA). Banks are to apply ECRA where regulators do allow the use of external ratings for regulatory purposes and weighted based on issue SCRA for regulators that don’t. specific rating while risk weights for unrated covered bonds will • Exposures to Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) be inferred from the issuer’s For exposures that do not fulfil the eligibility criteria, risk weights are to be determined by either SCRA or ECRA. -

Common Equity Capital, Banks' Riskiness and Required Return on Equity

IV SPECIAL FEATURES A COMMON EQUITY CAPITAL, BANKS’ previous regime, banks could hold as little as 2% RISKINESS AND REQUIRED RETURN of common equity as a share of risk-weighted ON EQUITY assets. The new rules demand a higher common equity ratio equal to 7% of risk-weighted assets, In the ongoing reform of the fi nancial system, i.e. the new minimum (4.5%) plus the capital a key regulatory objective is to increase the conservation buffer (2.5%).2 soundness and resilience of banks. In line with this objective, regulators have placed emphasis In addition to Basel III, a parallel strand of work on higher common equity capital requirements. has addressed systemically important fi nancial The industry has been critical of a higher institutions (SIFIs). Joint efforts by the Basel reliance on equity. Since equity is the most Committee and the Financial Stability Board expensive source of capital, it is often asserted have resulted in the publication of a consultative that higher equity ratios may materially increase document proposing a set of measures to initially banks’ funding costs, with adverse consequences be applied to global systemically important for credit availability. banks (G-SIBs).3 These measures are specifi cally designed to address the negative externalities and Based on a sample of large international banks, moral hazard posed by these fi rms. this special feature provides an assessment of the relationship between banks’ equity capital, According to the consultative document, G-SIBs riskiness and required return on equity. will need to satisfy additional loss-absorbency Following a methodology employed in recent requirements beyond Basel III. -

Pillar 3 (Basel Iii) Disclosures As on 31.03.2021 Central Bank of India

PILLAR 3 (BASEL III) DISCLOSURES AS ON 31.03.2021 CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA Table DF-1: Scope of Application (i) Qualitative Disclosures: The disclosure in this sheet pertains to Central Bank of India on solo basis. In the consolidated accounts (disclosed annually), Bank‟s subsidiaries/associates are treated as under a. List of group entities considered for consolidation Name of the Whether the Explain the Whether the Explain the Explain the Explain the entity / Country entity is method of entity is method of reasons for reasons if of incorporation included consolidation included consolidation difference in consolidated under under the method under only one accounting regulatory of of the scopes scope of scope of consolidation of consolidation consolidation consolidation (yes / no) (yes / no) Cent Bank Yes Consolidatio Yes NA NA NA Home Finance n of the Ltd./ India financial statements of subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 21. Cent Bank Yes Consolidatio Yes NA NA NA Financial n of the Services financial Ltd./India statements of subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 21 Uttar Bihar Yes Consolidatio No NA NA Associate: Gramin Bank, n of the Not under Muzzaffarpur/ financial scope of regulatory India statements of Consolidation subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 23 1 Uttar Banga Yes Consolidatio No NA NA Associate: Kshetriya n of the Not under Gramin Bank, financial scope of regulatory Cooch Behar/ statements of Consolidation India subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 23 Indo-Zambia Yes Consolidatio No NA NA Joint Bank Ltd. n of the Venture: Not /Zambia. financial under scope of regulatory statements of Consolidation subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 23 b. -

Navigating Through the Pandemic from a Position of Strength

Navigating Through the Pandemic from a Position of Strength Citi’s Commitment Supporting ICG Clients And Customers During these uncertain times, Citi remains well- Our ICG colleagues are working around the clock We are actively supporting our consumer clients positioned from a capital and liquidity to help our institutional clients navigate volatile through this unprecedented time. perspective. markets and manage their business needs as the • We continue to serve our customers while taking We have a strong balance sheet and will continue economic impacts of the pandemic continue to measures to help reduce the spread of COVID-19. to actively support our clients and customers evolve. As such, we have temporarily adjusted branch hours through this challenging period. • In BCMA, we continue lending to companies in and closed some locations. greatly affected industries, including airlines, leisure, • We were one of the first banks to announce industrials, autos and energy. We are helping blue assistance measures for impacted consumers and Key Financial Metrics chip multinationals strengthen their liquidity positions small businesses in the U.S. and are presenting clients with additional options to • Citibank's individual and Small Business customers (As of September 30, 2020) equitize and monetize. We are proud to work closely impacted by COVID-19 may be eligible for the Managing well through this crisis year-to-date with governments and the public sector to find following assistance measures, upon request. liquidity alternatives and have been working on the • Significant earnings power with ~$7B of net issuance of social bonds to support countries in the - Retail Bank: Fee waivers on monthly service income, despite ~$11B increase in credit Emerging Markets. -

Capital Adequacy Regulation (CAR)

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Central Bank of Myanmar Notification No. (16/2017) 14th Waxing Day of Waso 1379 ME July 7, 2017 ------------------------------------------------- In exercise of the powers conferred under Sections 34 and 184 of the Financial Institutions Law, the Central Bank of Myanmar hereby issues the following Regulations: 1. These Regulations shall be called Capital Adequacy Regulation (CAR). 2. These Regulations shall apply to all banks. 3. Capital Adequacy Ratio is a measure of the amount of a bank’s capital expressed as a percentage of its risk weighted assets. Banks are required to maintain the Capital Adequacy Ratio as follows: (a) Regulatory capital adequacy ratio is 8%; (b) The minimum Tier I Capital Adequacy Ratio is 4%. (c) In meeting the capital adequacy ratio, elements of Tier 2 or supplementary capital, may be included subject to approval of the Central Bank of Myanmar up to a maximum of 100% of Tier 1 or core capital. 4. A bank may increase its paid up capital by- (a) amendment to its constituent documents approved by the general meeting of the shareholders; and (b) the written approval of the Central Bank of Myanmar. 5. The initial paid-up capital and any subsequent increases in paid up capital must be deposited at the Central Bank of Myanmar. Subsequent to verification by the Central Bank of Myanmar, the bank may move the funds to their account. 6. Every bank must report the position of capital and capital adequacy ratio at the end of each month in the attached form to the Banking Supervision Department of the Central Bank of Myanmar. -

Capital-Instruments-Key-Features-Table

Capital instruments of UBS Group AG (consolidated) and UBS AG (consolidated and standalone) as of 31 March 2016 Key features Ordered by issuance date within each category Based on Swiss SRB Basel III phase-in requirements Issued on 4 May 2016 Share capital Additional Tier 1 capital instruments (Basel III compliant) Additional Tier 1 capital / Tier 2 capital instruments in the form of hybrid instruments and related subordinated notes (non-Basel III compliant) UBS Group AG, Switzerland, or other employing UBS Group AG, Switzerland, or other UBS Preferred Funding Trust IV UBS AG, Switzerland UBS Preferred Funding Trust V UBS AG, Switzerland 1 Issuer (country of incorporation; if applicable, branch) UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS AG, Switzerland entities of the Group employing entities of the Group Delaware, US Cayman branch Delaware, US Cayman branch 1a Instrument number 001 002 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 010 011 012 013 014 015 2 Unique identifier (e.g. ISIN) ISIN: CH0244767585 ISIN: CH0024899483 - ISIN: CH0271428309 ISIN: CH0271428317 ISIN: CH0271428333 ISIN: CH0286864027 - - ISIN: CH0317921697 - ISIN: US90263W2017 - ISIN: US90264AAA79 - 3 Governing law(s) of the instrument Swiss Swiss Swiss / NY, US Swiss law Swiss law Swiss law Swiss law Swiss law Swiss / NY, US Swiss law Swiss law Delaware, US NY, US Delaware, US NY, US Regulatory treatment 4 Transitional Basel III -

Regulatory Capital and Risk Management Pillar 3 Disclosures

2021 HSBC Bank Canada Regulatory Capital & Risk Management Pillar 3 Supplementary Disclosures As at March 31, 2021 HSBC Bank Canada Pillar 3 Supplementary Disclosure First Quarter 2021 1 Contents Page Notes to users 3 Road map to Pillar 3 disclosures 4 Capital and RWA 5 Regulatory Capital Disclosure - CC1 5 Overview of Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) - OV1 6 Credit Risk 6 RWA flow statements of credit risk exposures under IRB - CR8 6 Market Risk 6 RWA flow statements of market risk exposures under an Internal Model Approach (IMA) - MR2 7 Leverage Ratio 7 Summary comparison of accounting assets vs. leverage ratio exposure measure (LR1) 7 Leverage Ratio Common Disclosure (LR2) 8 Glossary 9 2 HSBC Bank Canada Pillar 3 Supplementary Disclosure First Quarter 2021 Notes to users Regulatory Capital and Risk Management Pillar 3 Disclosures The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (“OSFI”) supervises HSBC Bank Canada (the “Bank”) on a consolidated basis. OSFI has approved the Bank’s application to apply the Advanced Internal Ratings Based (“AIRB”) approach to credit risk on our portfolio and the Standardized Approach for measuring Operational Risk. Please refer to the Annual Report and Accounts 2020 for further information on the Bank’s risk and capital management framework. Further information regarding HSBC Group Risk Management Processes can be found in HSBC Holdings plc Capital and Risk Management Pillar 3 Disclosures available on HSBC Group’s investor relations web site. The Pillar 3 Supplemental Disclosures are additional summary -

2Q21 Net Profit of USD 2.0Bn, 19.3% Return on CET1 Capital

Investor Relations Tel. +41-44-234 41 00 Media Relations Tel. +41-44-234 85 00 Ad Hoc Announcement Pursuant to Article 53 of the SIX Exchange Regulation Listing Rules 2Q21 net profit of USD 2.0bn, 19.3% return on CET1 capital “We sustained our business momentum in 2Q21 as we continued to be a trusted partner for clients. Our focus on growth, relentless execution and evolution of our strategic initiatives drove strong financial performance across all businesses, resulting in a pre-tax profit of USD 2.6bn.” Ralph Hamers, Group CEO Group highlights We are executing We are delivering on We are committed relentlessly our strategic initiatives to driving higher for our clients to drive growth and returns by unlocking efficiency the power of UBS 2.0 0.55 19.3 14.5 USD bn USD % % Net profit Diluted earnings RoCET1 capital CET1 capital ratio attributable to per share UBS Group AG shareholders UBS’s 2Q21 results materials are available at ubs.com/investors The audio webcast of the earnings call starts at 09:00 CEST, 20 July 2021 UBS Group AG and UBS AG, Media Release, 20 July 2021 Page 1 of 17 Investor Relations Tel. +41-44-234 41 00 Media Relations Tel. +41-44-234 85 00 Group highlights We are executing relentlessly We are delivering on our strategic for our clients initiatives to drive growth and efficiency Our clients continued to put their trust in us as was During 1H21, we facilitated more than USD 18bn of evident from the continued momentum in flows and investments into private markets from private and volume growth. -

The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation Financial Supplement Fourth Quarter 2018 Table of Contents

The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation Financial Supplement Fourth Quarter 2018 Table of Contents Consolidated Results Page Consolidated Financial Highlights 3 Condensed Consolidated Income Statement 4 Condensed Consolidated Balance Sheet 5 Fee and Other Revenue 6 Average Balances and Interest Rates 7 Noninterest Expense 8 Capital and Liquidity 9 Key Market Metrics 10 Business Segment Results Investment Services Business 11 Investment Management Business 13 AUM by Product, AUM Flows and Wealth Management Client Assets 14 Other Segment 15 Other Investment Securities Portfolio 16 Allowance for Credit Losses and Nonperforming Assets 17 Supplemental Information – Explanation of GAAP and Non-GAAP Financial Measures 18 THE BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON CORPORATION CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (dollars in millions, except per common share amounts, or unless 4Q18 vs. FY18 vs. otherwise noted) 4Q18 3Q18 2Q18 1Q18 4Q17 3Q18 4Q17 FY18 FY17 FY17 Selected income statement data Fee revenue $ 3,146 $ 3,168 $ 3,209 $ 3,319 $ 2,886 (1)% 9 % $ 12,842 $ 12,162 6 % Net securities gains (losses) — — 1 (49) (26) N/M N/M (48) 3 N/M Fee and other revenue 3,146 3,168 3,210 3,270 2,860 (1) 10 12,794 12,165 5 (Loss) income from consolidated investment management funds (24) 10 12 (11) 17 N/M N/M (13) 70 N/M Net interest revenue 885 891 916 919 851 (1) 4 3,611 3,308 9 Total revenue 4,007 4,069 4,138 4,178 3,728 (2) 7 16,392 15,543 5 Provision for credit losses — (3) (3) (5) (6) N/M N/M (11) (24) N/M Noninterest expense 2,987 2,738 2,747 2,739 3,006 9 (1) 11,211 10,957 -

Education Note Lead Analyst Understanding Bank Capital UBS Financial Services, Inc

UBS Wealth Management Research / 26 March 2008 a b Education Note Lead analyst Understanding Bank Capital UBS Financial Services, Inc. Dean Ungar, CFA At a glance Asset Class: Equity This education note explains different capital measures used by regulators and analysts to assess the capital adequacy of US banking organizations. Capital adequacy moves onto the radar screen Large write-downs of securities backed by subprime mortgages along with increasing loan losses resulted in losses or minimal earnings per share at a number of US banks in 2007. Overall, earnings for the sector were down approximately 25% during the year. And stormy days are far from over. The outlook for 2008 includes further increases in loan losses and addi- tional credit costs as banks need to augment loan loss reserve levels. The pressure on bank earnings has had an adverse effect on bank capital levels. The average Tier 1 capital ratio (Tier 1 capital/risk-weighted assets) Chart 1 for US banks with market capitalization (cap) of USD 1 billion or more de- Tangible equity ratio – 10 largest banks clined from 11.2% as of 31 December, 2006 to 10.8% as of 31 Decem- ber, 2007. For the top 10 largest banks, the Tier 1 ratio declined from Tangible equity ratio - 10 largest banks 9.1% to 8.0% over the same period. Despite the decline, these ratios are 7.50 well above the 6.0% level that regulators consider well-capitalized. In fact, as of year-end 2007, there was no bank with market cap of USD 1 billion 7.00 or more with a Tier 1 ratio below 6.5%. -

Basel-Ii-Iii-Capital-Framework.Pdf

CAPITAL MEASUREMENT AND CAPITAL STANDARDS BASEL II/III CAPITAL DEFINITION AND PILLAR I FRAMEWORK January 2020 2 Table of contents ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Authority ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Purpose ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Minimum Capital Adequacy Requirement ......................................................................................... 6 1.5 Regulatory Reporting Requirements ................................................................................................. 6 1.6 Commencement ............................................................................................................................... 6 2 SCOPE OF APPLICATION ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Treatment of Significant Minority Investments ................................................................................