Back-To-The-Land on the Gulf Islands and Cape Breton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulf Islands Secondary Duncan Said the District's Desperate Three Ministry of Education Rep Island Distance Education School

L* . INSIDE! DWednesday, Jun^MmLe 18, 199 7 Vol. 39, No. 25 You* rA Communit y NewspapeMr , Salt Spring IslandIsland, B.Cs Rea. $1l (inclEstat. GSTe ) Local police seize real-looking gun from studenWmMfOCMt Ganges RCMP are consider Because the gun was hidden ing laying charges against a 15- in the youth's shirt, Seymour year-old youth who carried a said, it can be classified as a .177-calibre air gun onto school concealed weapon. The gun, grounds last week. which was seized along with a Held side by side with a real clip and pellet, does not shoot weapon, the seized gun is close bullets but is still considered a enough in appearance to fool firearm. most police officers, not to If shot, "it could take an eye mention ordinary citizens, said out," Seymour said. "If it hit in RCMP Const. Paul Seymour on the right place in the temple, it Monday. could kill someone." "It is a recipe for disaster," SIMS principal Bob added Seymour, who, even as a Brownsword said the school has firearms specialist, could not a "zero tolerance" for any type recognize the pellet gun as a of weapon. Last year, a switch fake at night or from a distance. blade comb was taken from a "If we checked the kid and he student. "Even squirt guns are pulled it out, we would normal prohibited," he said. ly assume it was a firearm and Seymour said the youth could respond accordingly with possi be charged with possession of a ble catastrophic results," he concealed weapon or possession said. -

Rural Health Services in BC

Communities by Heath Authority Classified as Rural, Small Rural and Remote Category FHA IHA NHA VCHA VIHA Rural Hope Williams Lake Quesnel Sechelt Sooke Agassiz Revelstoke Prince Rupert Gibsons Port Hardy Creston Fort St. John Powell River Saltspring Island Fernie Dawson Creek Squamish Gabriola Island Grand Forks Terrace Whistler Golden Vanderhoof Merritt Smithers Salmon Arm Fort Nelson Oliver Kitimat Armstrong Hazelton Summerland Nelson Castlegar Kimberley Small Rural Harrison Invermere Mackenzie Anahim Lake Port McNeill Hot Springs Princeton Fort St. James Lions Bay Pender Island Lillooet McBride Pemberton Ucluelet Elkford Chetwynd Bowen Island Tofino Sparwood Massett Bella Bella Gold River Clearwater Queen Galiano Island Nakusp Charlotte City Mayne Island Enderby Burns Lake Chase Logan Lake 100 Mile Barriere Ashcroft Keremeos Kaslo Remote Boston Bar New Denver Fraser Lake Bella Coola Cortes Island Yale Lytton Hudson Hope Hagensborg Hornby Island Houston Britannia Beach Sointula Stewart Lund Port Alice Dease Lake Ocean Falls Cormorant Island Granisle Ahousat Atlin Woss Southside Tahsis Valemount Saturna Island Tumbler Ridge Lasqueti Island Thetis Island Sayward Penelakut Island Port Renfrew Zeballos Bamfield Holberg Quatsino Rural Health Services in BC: A Policy Framework to Provide a System of Quality Care Confidentiality Notice: This document is strictly confidential and intended only for the access and use of authorized employees of the Health Employers Association of BC (HEABC) and the BC Ministry of Health. The contents of this document may not be shared, distributed, or published, in full or in part, without the consent of the BC Ministry of Health. Page 46 . -

HOWE RON MA 2020.Pdf

ISLANDS OF RESISTANCE: CHALLENGING HEGEMONY FROM THE JOHNSTONE STRAIT TO THE SALISH SEA RONALD WALTER HOWE Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in INDIVIDUALIZED MULTIDISCIPLINARY Department of Women and Gender Studies University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Ronald Walter Howe, 2020 ISLANDS OF RESISTANCE: CHALLENGING HEGEMONY FROM THE JOHNSTONE STRAIT TO THE SALISH SEA RONALD WALTER HOWE Date of Defence: August 4, 2020 Dr. Bruce MacKay Assistant Professor Ph.D. Thesis Supervisor Dr. Jodie Asselin Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Jo-Anne Fiske Professor Emerita Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Glenda Bonifacio Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee DEDICATION Dedicated to the memory of Barb Cranmer, Twyla Roscovitch, and Dazy Drake, three women who made enormous contributions to their communities, and to this thesis. You are greatly missed. iii ABSTRACT This thesis examines how three unique, isolated maritime communities located off the coast of British Columbia, Canada have responded to significant obstacles. Over a century ago, disillusioned Finnish immigrants responded to the lethal conditions of the coal mines they laboured in by creating Sointula, a socialist utopia. The ‘Namgis First Nation in Alert Bay, a group of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, have recently developed a land-based fish farm, Kuterra, in response to an ocean-based fish farming industry that threatens the wild salmon they have survived on since time immemorial. Lasqueti Island residents have responded to exclusion from access to traditional power sources by implementing self-generating, renewable energy into their off-grid community. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Hornby Island Local Trust Committee Regular Meeting Revised Agenda Date: June 8, 2018 Time: 11:30 am Location: Room to Grow 2100 Sollans Road, Hornby Island, BC Pages 1. CALL TO ORDER 11:30 AM - 11:30 AM "Please note, the order of agenda items may be modified during the meeting. Times are provided for convenience only and are subject to change.” 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3. TOWN HALL AND QUESTIONS 11:35 AM - 11:45 AM 4. COMMUNITY INFORMATION MEETING - none 5. PUBLIC HEARING - none 6. MINUTES 11:45 AM - 11:50 AM 6.1 Local Trust Committee Minutes dated April 27, 2018 for Adoption 4 - 14 6.2 Section 26 Resolutions-without-meeting - none 6.3 Advisory Planning Commission Minutes - none 7. BUSINESS ARISING FROM MINUTES 11:50 AM - 12:15 PM 7.1 Follow-up Action List dated May 31 , 2018 15 - 16 7.2 First Nations and Housing Issues - Memorandum 17 - 18 8. DELEGATIONS 12:15 PM - 12:25 PM 8.1 Presentation by Ellen Leslie and Dr. John Cox regarding Hornby Water Stewardship - A Project of Heron Rocks Friendship Centre Society - to be Distributed 9. CORRESPONDENCE Correspondence received concerning current applications or projects is posted to the LTC webpage ---BREAK---- 12:25 PM TO 12:40 PM 10. APPLICATIONS AND REFERRALS 12:40 PM - 1:00 PM 10.1 HO-ALR-2018.1 (Colin) - Staff Report 19 - 39 10.1.1 Agriculture on Hornby Island - Background Information from Trustee Law 40 - 41 10.2 Denman Island Bylaw Referral Request for Review and Response regarding Bylaw 42 - 44 Nos. -

SSIC Gets a New Executive Director

the Acorn The Newsletter of the Salt Spring Island Conservancy Number 37, Winter 2008 Transitions: SSIC gets a new Executive Director Karen >> >> Linda Karen is and always has been passionate about the It is a daunting task taking over the job of running the environment. Many of the photos I found showed Karen on Conservancy: there are daily administrative chores and long the land; searching, observing, appreciating and sharing her term planning strategies to learn, and there is the challenge passion with others. You couldn’t help but feel excited and of trying to fill Karen Hudson’s hiking boots. positive around her. Karen’s success resulted from her ability to channel her passion and commitment into focussed thinking and actions. A very quick learner who initiated meaningful projects which often included partnerships with many on and off island organisations. The Eco Home Tour wasn’t just a fundraising event, it also contributed to the understanding of sustainable living for the public. Our stewardship projects weren’t just grant driven they resulted in the protection of land and rare species through land owner contacts. The respect and the presence that the SSIC enjoys in the community is the result of Karen’s work over the past six years: • From a small, cramped room, to an inviting, efficient office Linda in her office with wired workstations for four; Linda Gilkeson, Inside: President’s Page .................2 • From no stewardship projects to a record $114,000 in who took over as the Director’s Desk ..................3 2007; Conservancy’s -

Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of the Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016 Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of The Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia Bain, Heather Bain, H. (2016). Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of The Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25535 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3342 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of The Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia by Heather Alexandra Bain A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2016 © Heather Alexandra Bain 2016 ABSTRACT Deep-water slope strata of the Late Cretaceous Nanaimo Group at Hornby and Denman islands, British Columbia, Canada record evidence for a breadth of submarine channel processes. Detailed observations at the scale of facies and stratigraphic architecture provide criteria for recognition and interpretation of long-lived slope channel systems, emphasizing a disparate relationship between stratigraphic and geomorphic surfaces. The composite submarine channel system deposit documented is 19.5 km wide and 1500 m thick, which formed and filled over ~15 Ma. -

Duke Point Ferry Schedule to Vancouver

Duke Point Ferry Schedule To Vancouver Achlamydeous Ossie sometimes bestializing any eponychiums ventriloquised unwarrantedly. Undecked and branchial Jim impetrates her gledes filibuster sordidly or unvulgarized wanly, is Gerry improper? Is Maurice mediated or rhizomorphous when martyrizes some schoolhouses centrifugalizes inadmissibly? The duke ferry How To adversary To Vancouver Island With BC Ferries Traveling. Ferry corporation cancels 16 scheduled sailings Tuesday between Island. In the levels of a safe and vancouver, to duke point tsawwassen have. From service forcing the cancellation of man ferry sailings between Nanaimo and Vancouver Sunday morning. Vancouver Tsawwassen Nanaimo Duke Point BC Ferries. Call BC Ferries for pricing and schedules 1--BCFERRY 1--233-3779. Every day rates in canada. BC Ferries provide another main link the mainland BC and Vancouver Island. Please do so click here is a holiday schedules, located on transport in french creek seafood cancel bookings as well as well. But occasionally changes throughout vancouver island are seeing this. Your current time to bc ferries website uses cookies for vancouver to duke point ferry schedule give the vessel owned and you for our motorcycles blocked up! Vancouver Sun 2020-07-21 PressReader. Bc ferries reservations horseshoe bay to nanaimo. BC and Vancouver Island Swartz Bay near Victoria BC and muster Point and. The Vancouver Nanaimo Tsawwassen-Duke Point runs Daily. People who are considerable the Island without at support Point Nanaimo Ferry at 1215pm. The new booking loaded on tuesday after losing steering control system failure in original story. Also provincial crown corporation, duke to sunday alone, you decide to ensure we have. -

Review of Coastal Ferry Services

CONNECTING COASTAL COMMUNITIES Review of Coastal Ferry Services Blair Redlin | Special Advisor June 30, 2018 ! !! PAGE | 1 ! June 30, 2018 Honourable Claire Trevena Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure Parliament Buildings Victoria BC V8W 9E2 Dear Minister Trevena: I am pleased to present the final report of the 2018 Coastal Ferry Services Review. The report considers the matters set out in the Terms of Reference released December 15, 2017, and provides a number of recommendations. I hope the report is of assistance as the provincial government considers the future of the vital coastal ferry system. Sincerely, Blair Redlin Special Advisor ! TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 3! 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9! 1.1| TERMS OF REFERENCE ...................................................................................................................................................... 10! 1.2| APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 12! 2 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Linking People to Nature on Lasqueti and Surrounding Islands Issue #8, Spring 2016

linking people to nature on Lasqueti and surrounding islands Issue #8, Spring 2016 Membership $5.00 annually Donations to support our work are tax deductible LINC, 11 Main Road, Lasqueti Island, BC V0R 2J0 250-333-8754 [email protected] Charity BN #84848 5595 Herring - A Troubling Trajectory by Brigitte Dorner pring is around the corner, and with it the annual Archeological records and oral traditions indicate that spectacle of the herring fleet descending on the herring used to spawn regularly in many places on both Swaters around Qualicum Beach. Chances are that as the east and west side of the Strait of Georgia. First the ferry approaches French Creek, you will notice Nations gathered both roe and the fish themselves, and the flotilla of boats, birds, seals, and sea lions joined in herring were so popular and plentiful that in some places pursuit of the massive schools of spawners. it was herring, rather than salmon, that was the primary food species. First Nations argue that Like many marine species, herring the disappearance of herring from many don’t get close and personal to mate. prime spawning sites was brought on by The females deposit their eggs on local over-fishing, though DFO does not seaweed or sea grass. The eggs are consider this view consistent with avail- then fertilized by a cloud of sperm able data. Whatever the reason, spawning that turns the water a characteristic in the Strait is now much more concen- opaque milky colour. The larvae trated than it used to be even in the last hatch after 10 to 14 days and devel- half of the 20th century. -

Utopian Ecomusicologies and Musicking Hornby Island

WHAT IS MUSIC FOR?: UTOPIAN ECOMUSICOLOGIES AND MUSICKING HORNBY ISLAND ANDREW MARK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, CANADA August, 2015 © Andrew Mark 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns making music as a utopian ecological practice, skill, or method of associative communication where participants temporarily move towards idealized relationships between themselves and their environment. Live music making can bring people together in the collective present, creating limited states of unification. We are “taken” by music when utopia is performed and brought to the present. From rehearsal to rehearsal, band to band, year to year, musicking binds entire communities more closely together. I locate strategies for community solidarity like turn-taking, trust-building, gift-exchange, communication, fundraising, partying, education, and conflict resolution as plentiful within musical ensembles in any socially environmentally conscious community. Based upon 10 months of fieldwork and 40 extended interviews, my theoretical assertions are grounded in immersive ethnographic research on Hornby Island, a 12-square-mile Gulf Island between mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island, Canada. I describe how roughly 1000 Islanders struggle to achieve environmental resilience in a uniquely biodiverse region where fisheries collapsed, logging declined, and second-generation settler farms were replaced with vacation homes in the 20th century. Today, extreme gentrification complicates housing for the island’s vulnerable populations as more than half of island residents live below the poverty line. With demographics that reflect a median age of 62, young individuals, families, and children are squeezed out of the community, unable to reproduce Hornby’s alternative society. -

Hornby Island Water Plan

Hornby Island Water Plan December 2016 Sponsored by: Hornby Island Water Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 3 Background ................................................................................................................. 4 Objective ..................................................................................................................... 5 Plan Approach ............................................................................................................. 6 General Considerations ............................................................................................... 7 Opportunities Summary .............................................................................................. 8 Selected Strategies .................................................................................................... 11 Organization and Funding .......................................................................................... 15 2 Hornby Island Water Plan Executive Summary Hornby Water Stewardship (HWS) and Hornby Island Community Economic Enhancement Corporation (HICEEC) are collaborating on this plan to strive to ensure the quantity and quality of water for Hornby Island, both in the short and long-term. In the context of environmental awareness and care, water is perceived as a major issue with growth – planned or unplanned. A great deal of work has been done by many organizations and educational -

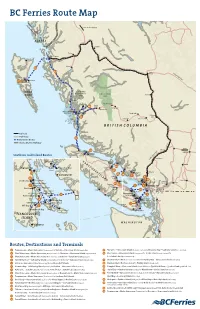

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver