Sindh Reading Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Supervisory System of School Education in Sindh Province of Pakistan

A STUDY OF THE SUPERVISORY SYSTEM OF SCHOOL EDUCATION IN SINDH PROVINCE OF PAKISTAN By Mc) I-i a mm aci. I sma i 1 13x--cptil Thesis submitted to the University of London in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration. Department of Curriculum Studies Institute of Education University of London March 1991 USSR r- • GILGIT AGENCY • PAKISTAN I ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS q PESH4WAA ISLAMABAD OCCUPIED KASHMIR ( • MIRPUR (AK) RAWALPINDI \., .L.d.) 1■ •-....., CO f ) GUJRAT • --"'-',. • GUJRANWALA X' / 1).--1. •• .'t , C, p.'fj\.,./ ' • X • •• FAISALABAD LAHORE- NP* ... -6 , / / PUNJAB • ( SAHIWAL , / • ....-• .1 • QUETTA MULTAN I BALUCHISTAN RAHIMYAR KHAN/ • .1' \ •,' cc SINDH MIRPURKHAS %.....- \ • .■. • HYDERABAD •( ARABIAN SEA ABSTRACT The role of the educational supervisor is pivotal in ensuring the working of the system in accordance with general efficiency and national policies. Unfortunately Pakistan's system of educational management and supervision is too much entrenched in the legacy of past and has not succeeded, over the last forty years, in modifying and reforming itself in order to cope with the expanding and changing demands of eduCation in the country since independence( i.e. 1947). The empirical findings of this study support the following. Firstly, the existing style of supervision of secondary schools in Sindh, applied through traditional inspection of schools, is defective and outdated. Secondly, the behaviour of the educational supervisor tends to be too rigid and autocratic . Thirdly, the reasons for the resistance of existing system of supervision to change along the lines and policies formulated in recent years are to be found outside the education system and not merely within the education system or within the supervisory sub-system. -

Teacher Education Policies and Programs in Pakistan

TEACHER EDUCATION POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN PAKISTAN: THE GROWTH OF MARKET APPROACHES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TRADITIONAL TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS By Fida Hussain Chang A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education - Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT TEACHER EDUCATION POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN PAKISTAN: THE GROWTH OF MARKET APPROACHES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TRADITIONAL TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS By Fida Hussain Chang Two significant effects of globalization around the world are the decentralization and liberalization of systems, including education services. In 2000, the Pakistani Government brought major higher education liberalization and expansion reforms by encouraging market approaches based on self-financed programs. These approaches have been particularly important in the area of teacher education and development. The Pakistani Government data reports (AEPAM Islamabad) on education show vast growth in market-model off-campus (open and distance) post-baccalaureate teacher education programs in the last fifteen years. Many academics and scholars have criticized traditional off-campus programs for their low quality; new policy reforms in 2009, with the support of USAID, initiated the four-year honors program, with the intention of phasing out all traditional programs by 2018. However, the new policy still allows traditional off-campus market-model programs to be offered. This important policy reform juncture warrants empirical research on the effectiveness of traditional programs to inform current and future policies. Thus, this study focused on assessing the worth of traditional and off-campus programs, and the effects of market approaches, on the implementation of traditional post-baccalaureate teacher education programs offered by public institutions in a southern province of Pakistan. -

Capturing the Demographic Dividend in Pakistan

CAPTURING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN PAKISTAN ZEBA A. SATHAR RABBI ROYAN JOHN BONGAARTS EDITORS WITH A FOREWORD BY DAVID E. BLOOM The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. © 2013 The Population Council, Inc. Population Council One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza New York, NY 10017 USA Population Council House No. 7, Street No. 62 Section F-6/3 Islamabad, Pakistan http://www.popcouncil.org The United Nations Population Fund is an international development agency that promotes the right of every woman, man, and child to enjoy a life of health and equal opportunity. UNFPA supports countries in using population data for policies and programmes to reduce poverty and to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every birth is safe, every young person is free of HIV and AIDS, and every girl and woman is treated with dignity and respect. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capturing the demographic dividend in Pakistan / Zeba Sathar, Rabbi Royan, John Bongaarts, editors. -- First edition. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-87834-129-0 (alkaline paper) 1. Pakistan--Population--Economic aspects. 2. Demographic transition--Economic aspects--Pakistan. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Graduates Directory Spring 2019

2019 COOP PROGRAM Short for Cooperative Education - Classroom Based Learning + Work Based Learning Skill Impact Bytes of Coop Program Structured Program enabling university students to learn classroom theory with practical, hands-on experience in industry prior to graduation. Industry to prepare itself requires a framework for product strategy which is insight driven and well thought-out so that it can satisfy the hidden need of the market. Through Coop Program the product, i.e “The Graduate”, is the one who will be insightful with ability to think through the dynamics of Congratulations! the competition and the consumer and come out with winning solutions - for that we are preparing this coop program. Office of Career Services (OCS) has been rebranded as Create a pipeline of future candidates i.e Succession Planning Office of Corporate Linkages and Placements (OCLP) Recruit with low risk On graduation fully Trained Talent with no down time Low Recruitment/training costs Get new/creative ideas for the organization Faculty engagement COOP PROGRAM Short for Cooperative Education - Classroom Based Learning + Work Based Learning Skill Impact Bytes of Coop Program Structured Program enabling university students to learn classroom theory with practical, hands-on experience in industry prior to graduation. Industry to prepare itself requires a framework for product strategy which is insight driven and well thought-out so that it can satisfy the hidden need of the market. Through Coop Program the product, i.e “The Graduate”, is the one who will be insightful with ability to think through the dynamics of Congratulations! the competition and the consumer and come out with winning solutions - for that we are preparing this coop program. -

Comparative Analysis of Public and Private Educational Institutions: a Case Study of District Vehari-Pakistan

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.16, 2015 Comparative Analysis of Public and Private Educational Institutions: A case study of District Vehari-Pakistan. Prof.Dr.Abdul Ghafoor Awan Dean, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences, Institute of Southern Punjab,Multan-Pakistan. Cell# 0313-6015051. Asma Zia, M.Phil Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Institute of Southern Punjab,Multan-Pakistan. Abstract Education is necessary for the personality grooming of individual. There are different types of institutions available like private and public institutions, technical institutions, and madrasas (religious institutions). These institutes are having the triangle of three main pillars; consisted of Teachers, Students, and Curriculum. There are two main types of schools in Pakistan and all over the world. One is public and other is private school system. Now a days private schools are becoming more favorite and attractive for majority of the students due to their better education systems, test criteria and knowledge creation vis-a-vis public schools, which comparatively very cheap but inefficient are losing their attraction. Parents prefer to send their children in private schools and avoid public schools. The main objective of this study is to investigate why people prefer high charging private schools over free public schools (That charge nothing)? We use primary data collected through constructed questionnaire and survey method was applied for collection of data from the target respondents of private and public schools located in District Vehari, Pakistan. The results show that five main factors emerge as important determinants of private school choice. -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

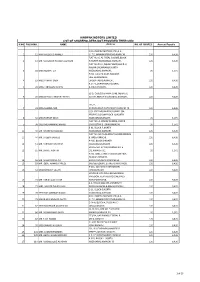

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Best Corporate and Sustainability Report 2015 Awards Ceremony

www.icap.org.pk Volume 39 Issue 10 | October 2016 NewsletterGovernance, Transparency and Service to Members and Students contents meets & events meets & events Best Corporate and Sustainability Appointment at IFAC Committees 8 Report 2015 Awards Ceremony ICAP Distributes Awards Nationally to Top Position Holders Seminar on Success in Professional Life 10 National Finance Olympiad is back! 11 CA Toastmasters Club Islamabad CA Toastmasters Club Lahore 12 member news Top 5 CPD Earners 13 New Fellow/Associate Members Obituary Life Member New Firms 14 The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan (ICAP) and Institute of Discount Cost and Management Accountants of Pakistan (ICMAP) jointly organised Continuing Professional Development the fifteenth Best Corporate and Sustainability Report (BCSR) 2015 Program Awards Ceremony on October 7, 2016 at Movenpick Hotel, Karachi. hr news The chief minister Sindh, Syed Murad Ali Shah was the chief guest, and Traits of Leadership guests of honour included past presidents ICAP, Saqib Masood and Shabbar Zaidi and past presidents ICMAP, M. A. Lodhi and Ashraf Bawany. Welcome on Board 16 Training & Development Shah said that Sindh government intended to have partnership with private sector and accountancy professionals for economic growth to help ICAP Staff Performs Hajj improve the economy of the province as well as that of the country. The chief minister appreciated ICAP and ICMAP for jointly organising these student section awards every year for the enhancement of corporate reporting system and Career Counselling Sessions 17 said that high quality financial reports of the companies are pivotal for the development of the country. He urged the corporate sector to invest in the Learn & Lunch Session with province as it has potential of robust economic growth. -

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity.