1 Rhetoric in Ancient China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ps TOILETRY CASE SETS ACROSS LIFE and DEATH in EARLY CHINA (5 C. BCE-3 C. CE) by Sheri A. Lullo BA, University of Chicago

TOILETRY CASE SETS ACROSS LIFE AND DEATH IN EARLY CHINA (5th c. BCE-3rd c. CE) by Sheri A. Lullo BA, University of Chicago, 1999 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2009 Ps UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Sheri A. Lullo It was defended on October 9, 2009 and approved by Anthony Barbieri-Low, Associate Professor, History Dept., UC Santa Barbara Karen M. Gerhart, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Bryan K. Hanks, Associate Professor, Anthropology Anne Weis, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Katheryn M. Linduff, Professor, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Sheri A. Lullo 2009 iii TOILETRY CASE SETS ACROSS LIFE AND DEATH IN EARLY CHINA (5th c. BCE-3rd c. CE) Sheri A. Lullo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 This dissertation is an exploration of the cultural biography of toiletry case sets in early China. It traces the multiple significances that toiletry items accrued as they moved from contexts of everyday life to those of ritualized death, and focuses on the Late Warring States Period (5th c. BCE) through the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), when they first appeared in burials. Toiletry case sets are painted or inlaid lacquered boxes that were filled with a variety of tools for beautification, including combs, mirrors, cosmetic substances, tweezers, hairpins and a selection of personal items. Often overlooked as ordinary, non-ritual items placed in burials to comfort the deceased, these sets have received little scholarly attention beyond what they reveal about innovations in lacquer technologies. -

The Qin Dynasty Laura Santos

Level 6 - 10 China’s First Empire: The Qin Dynasty Laura Santos Summary This book is about the Qin Dynasty—both the good and the bad. Contents Before Reading Think Ahead ........................................................... 2 Vocabulary .............................................................. 3 During Reading Comprehension ...................................................... 5 After Reading Think About It ........................................................ 8 Before Reading Think Ahead Look at the pictures and answer the questions. watchtower The Great Wall of China underground sightseeing statues 1. What did guards along the Great Wall use to see invaders? 2. What are most people doing when they visit the Great Wall today? 3. What are the people and horses in the second picture called? 4. Where were these people and horses found? 2 World History Readers Before Reading Vocabulary A Read and match. 1. a. fake 2. b. mercury 3. c. jewels 4. d. wagon 5. e. scholar 6. f. statue 7. g. sightseeing 8. h. chariot China’s First Empire: The Qin Dynasty 3 Before Reading B Write the word for each definition. evidence messenger ban tomb suicide 1. the act of taking one’s own life 2. a person who carries news or information from one person to another 3. a place or building to keep a dead person 4. one or more reasons for believing that something is or is not true 5. to forbid; to refuse to allow C Choose the word that means about the same as the underlined words. 1. The emperor sent many soldiers up the Yellow River to watch for foreign enemies. a. invaders b. scholars c. chariots d. messengers 2. The emperor built a fancy tomb for himself. -

Mohist Theoretic System: the Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections with the Universal Values and Global Sustainability

Cultural and Religious Studies, March 2020, Vol. 8, No. 3, 178-186 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.03.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Mohist Theoretic System: The Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections With the Universal Values and Global Sustainability SONG Jinzhou East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Mohism was established in the Warring State period for two centuries and half. It is the third biggest schools following Confucianism and Daoism. Mozi (468 B.C.-376 B.C.) was the first major intellectual rivalry to Confucianism and he was taken as the second biggest philosophy in his times. However, Mohism is seldom studied during more than 2,000 years from Han dynasty to the middle Qing dynasty due to his opposition claims to the dominant Confucian ideology. In this article, the author tries to illustrate the three potential functions of Mohism: First, the critical/revision function of dominant Confucianism ethics which has DNA functions of Chinese culture even in current China; second, the interconnections with the universal values of the world; third, the biological constructive function for global sustainability. Mohist had the fame of one of two well-known philosophers of his times, Confucian and Mohist. His ideas had a decisive influence upon the early Chinese thinkers while his visions of meritocracy and the public good helps shape the political philosophies and policy decisions till Qin and Han (202 B.C.-220 C.E.) dynasties. Sun Yet-sen (1902) adopted Mohist concepts “to take the world as one community” (tian xia wei gong) as the rationale of his democratic theory and he highly appraised Mohist concepts of equity and “impartial love” (jian ai). -

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy

Readings In Classical Chinese Philosophy edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe University of Michigan and Bryan W. Van Norden Vassar College Seven Bridges Press 135 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010-7101 Copyright © 2001 by Seven Bridges Press, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Publisher: Ted Bolen Managing Editor: Katharine Miller Composition: Rachel Hegarty Cover design: Stefan Killen Design Printing and Binding: Victor Graphics, Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Readings in classical Chinese philosophy / edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe, Bryan W. Van Norden. p. cm. ISBN 1-889119-09-1 1. Philosophy, Chinese--To 221 B.C. I. Ivanhoe, P. J. II. Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William) B126 .R43 2000 181'.11--dc21 00-010826 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CHAPTER TWO Mozi Introduction Mozi \!, “Master Mo,” (c. 480–390 B.C.E.) founded what came to be known as the Mojia “Mohist School” of philosophy and is the figure around whom the text known as the Mozi was formed. His proper name is Mo Di \]. Mozi is arguably the first true philosopher of China known to us. He developed systematic analyses and criticisms of his opponents’ posi- tions and presented an array of arguments in support of his own philo- sophical views. His interest and faith in argumentation led him and his later followers to study the forms and methods of philosophical debate, and their work contributed significantly to the development of early Chinese philosophy. -

Mozi 31: Explaining Ghosts, Again Roel Sterckx* One Prominent Feature

MOZI 31: EXPLAINING GHOSTS, AGAIN Roel Sterckx* One prominent feature associated with Mozi (Mo Di 墨翟; ca. 479–381 BCE) and Mohism in scholarship of early Chinese thought is his so-called unwavering belief in ghosts and spirits. Mozi is often presented as a Chi- nese theist who stands out in a landscape otherwise dominated by this- worldly Ru 儒 (“classicists” or “Confucians”).1 Mohists are said to operate in a world clad in theological simplicity, one that perpetuates folk reli- gious practices that were alive among the lower classes of Warring States society: they believe in a purely utilitarian spirit world, they advocate the use of simple do-ut-des sacrifices, and they condemn the use of excessive funerary rituals and music associated with Ru elites. As a consequence, it is alleged, unlike the Ru, Mohist religion is purely based on the idea that one should seek to appease the spirit world or invoke its blessings, and not on the moral cultivation of individuals or communities. This sentiment is reflected, for instance, in the following statement by David Nivison: Confucius treasures the rites for their value in cultivating virtue (while virtually ignoring their religious origin). Mozi sees ritual, and the music associated with it, as wasteful, is exasperated with Confucians for valuing them, and seems to have no conception of moral self-cultivation whatever. Further, Mozi’s ethics is a “command ethic,” and he thinks that religion, in the bald sense of making offerings to spirits and doing the things they want, is of first importance: it is the “will” of Heaven and the spirits that we adopt the system he preaches, and they will reward us if we do adopt it. -

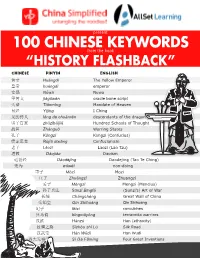

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

1 Paradoxes in the School of Names1 Chris Fraser University of Hong

1 Paradoxes in the School of Names1 Chris Fraser University of Hong Kong Introduction Paradoxes are statements that run contrary to common sense yet seem to be supported by reasons and in some cases may turn out to be true. Paradoxes may be, or may entail, explicit contradictions, or they may simply be perplexing statements that run beyond or against what seems obviously correct. They may be proposed for various reasons, such as to overturn purportedly mistaken views, to illustrate problematic logical or conceptual relations, to reveal aspects of reality not reflected by received opinion, or simply to entertain. In the Western philosophical tradition, the earliest recognized paradoxes are attributed to Zeno of Elea (ca. 490–430 B.C.E.) and to Eubulides of Miletus (fl. 4th century B.C.E.). In the Chinese tradition, the earliest and most well-known paradoxes are ascribed to figures associated with the “School of Names” (ming jia 名家), a diverse group of Warring States (479–221 B.C.E.) thinkers who shared an interest in language, logic, and metaphysics. Their investigations led some of these thinkers to propound puzzling, paradoxical statements such as “Today go to Yue but arrive yesterday,” “White horses are not horses,” and “Mountains and gorges are level.” Such paradoxes seem to have been intended to highlight fundamental features of reality or subtleties in semantic relations between words and things. Why were thinkers who advanced paradoxes categorized as a school of “names”? In ancient China, philosophical inquiry concerning language and logic focused on the use of “names” (ming 名, also terms, labels, or reputation) and their semantic relations to “stuff” (shi 實, also objects, features, events, or situations). -

View Sample Pages

This Book Is Dedicated to the Memory of John Knoblock 未敗墨子道 雖然歌而非歌哭而非哭樂而非樂 是果類乎 I would not fault the Way of Master Mo. And yet if you sang he condemned singing, if you cried he condemned crying, and if you made music he condemned music. What sort was he after all? —Zhuangzi, “In the World” A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. Although the institute is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. The China Research Monograph series is one of the several publication series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. Send correspondence and manuscripts to Katherine Lawn Chouta, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies 2223 Fulton Street, 6th Floor Berkeley, CA 94720-2318 [email protected] Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. [Mozi. English. Selections] Mozi : a study and translation of the ethical and political writings / by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel. pages cm. -- (China research monograph ; 68) English and Chinese. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-103-9 (alk. paper) 1. Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. Mozi. I. Knoblock, John, translator, writer of added commentary. II. Riegel, Jeffrey K., 1945- translator, writer of added commentary. III. Title. B128.M79E5 2013 181'.115--dc23 2013001574 Copyright © 2013 by the Regents of the University of California. -

Foreigners and Propaganda War and Peace in the Imperial Images of Augustus and Qin Shi Huangdi

Foreigners and Propaganda War and Peace in the Imperial Images of Augustus and Qin Shi Huangdi This thesis is presented by Dan Qing Zhao (317884) to the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the field of Classics in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies Faculty of Arts University of Melbourne Principal Supervisor: Dr Hyun Jin Kim Secondary Supervisor: Associate Professor Frederik J. Vervaet Submission Date: 20/07/2018 Word Count: 37,371 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Translations and Transliterations ii Introduction 1 Current Scholarship 2 Methodology 7 Sources 13 Contention 19 Chapter One: Pre-Imperial Attitudes towards Foreigners, Expansion, and Peace in Early China 21 Western Zhou Dynasty and Early Spring and Autumn Period (11th – 6th century BCE) 22 Late Spring and Autumn Period (6th century – 476 BCE) 27 Warring States Period (476 – 221 BCE) 33 Conclusion 38 Chapter Two: Pre-Imperial Attitudes towards Foreigners, Expansion, and Peace in Rome 41 Early Rome (Regal Period to the First Punic War, 753 – 264 BCE) 42 Mid-Republic (First Punic War to the End of the Macedonian Wars, 264 – 148 BCE) 46 Late Republic (End of the Macedonian Wars to the Second Triumvirate, 148 – 43 BCE) 53 Conclusion 60 Chapter Three: Peace through Warfare 63 Qin Shi Huangdi 63 Augustus 69 Conclusion 80 Chapter Four: Morality, Just War, and Universal Consensus 82 Qin Shi Huangdi 82 Augustus 90 Conclusion 104 Chapter Five: Victory and Divine Support 106 Qin Shi Huangdi 108 Augustus 116 Conclusion 130 Conclusion 132 Bibliography 137 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer my sincerest thanks to Dr Hyun Jin Kim. -

Manufacturing Techniques of Armor Strips Excavated from Emperor Qin Shi Huang’S Mausoleum, China

Manufacturing techniques of armor strips excavated from Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum, China LIAO Ling-min(廖灵敏)1, PAN Chun-xu(潘春旭)1,2, MA Yu(马 宇)3 1. Department of Physics, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China; 2. Center for Archaeometry, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China; 3. Museum of the Terra-cotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shi Huang, Xi’an 710600, China Received 17 February 2009; accepted 17 June 2009 Abstract: The chemical compositions and microstructures of the armor strips excavated from the Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum were examined systematically by using optical microscopy and electron microscopy. It was found that the armor strips were made of pure copper. Based on the morphology of α-Cu recrystal grain and copper sulphide (Cu2S) inclusions in the armor strips, the manufacturing techniques were proposed as follows: smelting pure copper, casting a lamellar plate, forming the cast ingots into sheets through repeated cold forging combined with annealing heat treatment, and finally cutting the sheets into filaments. Furthermore, through the deformation of copper sulphide (Cu2S) inclusions in the strips, the work rate during forging was evaluated and calculated to be close to 75%. Key words: Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum; armor strips; copper; manufacturing techniques; cold forging; annealing complex techniques were employed. However, the 1 Introduction ancient technicians could not manufacture such slender armor strips with the same process in the productive In 1998, the stone armors were excavated in the condition over 2 000 years ago. As a matter of fact, accessory pit K9801 of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s following the flourishing period for bronze, Spring and mausoleum[1]. -

Daoism and Daoist Art

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Daoism and Daoist Art Works of Art (19) Essay Indigenous to China, Daoism arose as a secular school of thought with a strong metaphysical foundation around 500 B.C., during a time when fundamental spiritual ideas were emerging in both the East and the West. Two core texts form the basis of Daoism: the Laozi and the Zhuangzi, attributed to the two eponymous masters, whose historical identity, like the circumstances surrounding the compilation of their texts, remains uncertain. The Laozi—also called the Daodejing, or Scripture of the Way and Virtue—has been understood as a set of instructions for virtuous rulership or for self- cultivation. It stresses the concept of nonaction or noninterference with the natural order of things. Dao, usually translated as the Way, may be understood as the path to achieving a state of enlightenment resulting in longevity or even immortality. But Dao, as something ineffable, shapeless, and conceived of as an infinite void, may also be understood as the unfathomable origin of the world and as the progenitor of the dualistic forces yin and yang. Yin, associated with shade, water, west, and the tiger, and yang, associated with light, fire, east, and the dragon, are the two alternating phases of cosmic energy; their dynamic balance brings cosmic harmony. Over time, Daoism developed into an organized religion—largely in response to the institutional structure of Buddhism—with an ever-growing canon of texts and pantheon of gods, and a significant number of schools with often distinctly different ideas and approaches. At times, some of these schools were also politically active. -

2015 Sample Topic Ideas

2015 Sample Topics List • Benjamin Franklin and the Library Company of • The Three Leaders: Mazzini, Garibaldi, Cavour and the Philadelphia: A New Intellectual Nation • Charlemagne’s Conquest and its Impact on European • TheUnification International of Italy Space Station: Leading an International Architecture Effort to Unite Space • Mikhail Gorbechev: Leading a Struggling Nation out of the • Cold War Presidency The Iran Hostage Crisis: Defining the Leadership of a • The Euro: How the European Union Led the Movement for • Thomas Paine’s Revolutionary Writings Economic Integration • Bacon’s Rebellion and the Growth of Slavery in Colonial • William Howard Taft and Dollar Diplomacy • The World Health Organization: Leading the Fight to • TheVirginia Bloodless Revolution of 1800: John Adams, Thomas Eradicate Communicable Disease Jefferson, and the Legacy of a Peaceful Transition of Power • Yoga Bonita: How Brazil Led a Soccer Revolution • Andrew Jackson: The Legacy of the People’s President • Globalization of McDonalds: American Corporations • Invoking the Power of the Federal Government: Grover Leading the World’s Economy Cleveland and the Pullman Strike of 1894 • Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev: Leading the World • Alice Paul: Leading the Movement for Equal Rights Out of the Cold War • Leading the Charge to Legislate Equality: Lyndon B. • • ThePierre Legacy de Coubertin of King Leopold’s and the Rebirth Vision ofin the InternationalCongo • A.Johnson Philip andRandolph: the Voting Leading Rights the Act Way to Integrate America’s Olympic