Shashthi's Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Nature in the Ashoka Shashthi Vrata Katha of Bengal

11 Separated by the text: Women and Nature in the Ashoka Shashthi Vrata Katha of Bengal Namrata Rathore Mahanta* Abstract: Ashoka Shasthi Vrata is a popular vrata practiced by women in West Bengal for the long life and well-being of children. Celebrated in the month of Chaitra, the vrata is dedicated to the Puranic goddess Shashthi. The vrata rites involve the ritual narration of a story (katha) associated with the vrata. The narrative moves around the life of an abandoned female infant named Ashoka, found under an Ashoka tree in a hermitage and her subsequent encounter with the benevolent and malevolent aspects of the goddess Shashthi. The present paper focusses on the relationship between Ashoka and the flora and fauna in the hermitage in an attempt to read the Ashoka Shasthi Vrata Katha as a narrative of empowerment achieved through bonding between women and nature. Keywords: Women, Nature, Mother Goddesses, Puranas, Vratas, Motherhood omen‟s vratas are simple rituals performed for wish fulfillment and W are distinct from the other kinds of scriptural vratas. The present day women‟s vratas are remnants of primordial rites variously transformed through the puranic tradition. In Bengal, women‟s vratas are termed „ashastriya‟ or „meyeli vratas. Ashoka Shashthi is a popular vrata practiced by women of Bengal for the long life and well-being of their children. Celebrated in the month of Chaitra, the vrata is dedicated to the Puranic goddess Shashthi. The vrata rites involve the ritual narration of a story (katha) associated with the vrata. The narrative of the Ashoka Shashthi Vrata Katha moves around Ashoka, an infant found lying under an Ashoka tree near a hermitage. -

BHAKTI Temple Hours Mon to Fri: 9 AM – 12:30 PM & 4 PM – 8:30 PM January 2011

Greater Cleveland Shiva Vishnu Temple A Non-profit 7733 Ridge Road Organization P.O. Box 29508 US POSTAGE Parma, OH 44129 PAID Cleveland, OH Permit No. 03879 Phone (440) 888-9433 www.shivavishnutemple.org A Non-Profit Tax-Exempt Organization REGULAR WEEKLY & MONTHLY PUJA SCHEDULE Sunday 9:30 AM Shiva Abhishekam; 11 AM Vishnu Puja st rd 1 Sunday 12:30 PM Jagannath Puja 3 Sunday 12:30 PM Jain Puja Monday 10 AM Shiva Abhishekam; 6 PM Jagannath Puja Tuesday 10 AM Ganesha Abhishekam; 6 PM Hanumanji Puja Wednesday 10 AM Ram Parivar Puja 6 PM Aiyappa Puja; Thursday 10 AM Radha Krishna Puja; 6 PM Shrinathji Puja: Friday 10 AM Parvati Puja (Abhishekam 1st Fri 7:15 p) 6 PM Lakshmi Puja: 6:30 PM Durga Puja 7:15 PM Abhishekam for Sridevi 2nd Fri for Bhudevi 3rd Friday (7:15 p) Saturday 11 AM Vishnu Abhishekam 10 AM Aiyappa Puja 1st Sat 5 PM Karthikeya Puja 6 PM Saraswati Puja; 6:30 PM Navagraha Abhishek 11 AM Venkateswara Abhishekam 2nd & 4th Sat Puja 1st &3rd Sat NITYA PUJA (Monday – Saturday ) 10 AM Shiva Abhishekam; 10 AM Vishnu Puja Highlights of Feb 2011 events Date Day Time Description Feb 2 Wed Amavasya Feb 5 Sat 10 a Sri Aiyappa Puja Feb 7 Mon 10 a Vasant PanchamiSri Saraswati Puja Feb 8 Tue 6 p Sukla Shashthi, Murugabhishekam Feb 17 Wed 7.15 p Pournima, Satyanarayanpuja Feb 20 Sat 6 p Sankatahara Chaturthi,Ganeshabhishekam Mar 2 Wed 6 p Mahashivaratri Visitors are requested to wear appropriate attire in the Temple premises 10pm Mini Aarati Bhajan,Prasad Greater Cleveland Shiva Vishnu Temple BHAKTI Temple Hours Mon to Fri: 9 AM – 12:30 PM -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Greater Cleveland Shiva Vishnu Temple

GREATER CLEVELAND SHIVA VISHNU TEMPLE Schedule of Activities: 2014 Date Day Time Description Date Day Time Description Jan 1 Wed 9:15 a New Year Day, Ganesh Havan, Jul 2 Wed 6 p Sukla Shashti Murugabhishekam 11 a Venkateswara Abhishekam Jul 8 Tue 9 a Gowri Vrat, (ends July 12th Sat) 11 a Satsang, Bhajan, Aarati (Main temple hall) Jul 10 Thu 9 a Jayaparvati Vrat, (ends July 14th Mon) Jan 4 Sat 10 a Sri Aiyappa Puja (1) Jul 11 Fri 7.15 p Guru Pournima, Satyanarayana Puja Jan 5 Sun 1 p ScheduleSri Jagannath of Activities: Puja (2) 2004 Jul 13 Sun 11:45a Hindola Puja ends Thu 8/12 (4) 6 p Sukla Shashti (Murugabhishekam) Jul 14 Mon 6 p Sankathara Chaturthi, Ganeshabhihsekam Jan 11 Sat 9 a Vaikunta Ekadashi Jul 16 Wed Dakshinayana Punyakala 10 a Sri Aiyappa Makara Vilakku Puja Celebration Jul 23 Wed 6 p Pradosham, Rudrabhishekam 11 a Venkateswara Abhishekam Jul 26 Sat Amavasya 5:30 p Festival of Lohri Jul 28 Mon 6 p Shravan Somavar: Rudrabhishekam (5) Jan 12 Sun 11:30 a Makara Sankranti & Pongal Celebration Jul 31 Thu Garudapanchami Jan 14 Tue 9:30 a Makara Sankranti, Suryanarayan Puja Aug 1 Fri 6 p Sukla Shashti (Murugabhishekam) Uttarayana Punyakala Aug 8 Fri 7:15 p Varalakshmi Vratam 6p Sri Aiyappa Makara Vilakku Puja Aug 9 Sat 7:15 p Pournima, Satyanarayanpuja, Raksha Bandhan. Jan 15 Wed 7.15 p Pournima,Satyanarayanpuja Aug 10 Sun 7 a Yajur Rik Upakarma, Gayathri japam Jan 16 Thu 6 p Tai Poosam (Murugabhishekam) Aug 13 Wed 6 p Sankatahara Chaturthi,Ganeshabhishekam 6:30 p Sri Srinathji Puja (3) Aug 16 Sat 9 p Krishna Janmashtami Puja, Bhajan,Arti -

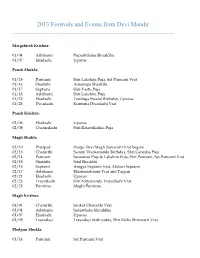

2013 Festivals and Events from Devi Mandir

2013 Festivals and Events from Devi Mandir Margshirsh Krishna: 01/04 Ashthami Pupashthaka Shraddha 01/07 Ekadashi Upavas Paush Shukla: 01/15 Pancami Shri Lakshmi Puja, Sat Pancami Vrat 01/16 Shashthi Annarupa Shashthi 01/17 Saptami Shri Vastu Puja 01/18 Ashthami Shri Lakshmi Puja 01/22 Ekadashi Trailinga Swami Birthday, Upavas 01/23 Dwadashi Kurmma Dwadashi Vrat Paush Krishna: 02/06 Ekadashi Upavas 02/08 Chaturdashi Shri Ratantikalika Puja Magh Shukla: 02/10 Pratipad Durga Devi Magh Navaratri Vrat begins 02/13 Chaturthi Swami Vivekananda Birthday, Shri Ganesha Puja 02/14 Pancami Saraswati Puja & Lakshmi Puja, Shri Pancami, Sat Pancami Vrat 02/15 Shashthi Sital Shashthi 02/16 Saptami Arogya Saptami Vrat, Makari Saptami 02/17 Ashthami Bhishmashtami Vrat and Tarpan 02/21 Ekadashi Upavas 02/23 Trayodashi Shri Nityananda Trayodashi Vrat 02/25 Purnima Maghi Purnima Magh Krishna: 03/01 Chaturthi Sankat Chaturthi Vrat 03/04 Ashthami Sakasthaka Shraddha 03/07 Ekadashi Upavas 03/09 Trayodasi Trayodasi nishi yukta, Shri Maha Shivaratri Vrat Phalgun Shukla: 03/16 Pancami Sat Pancami Vrat 03/17 Shashthi Gorupini Shashthi 03/22 Ekadashi Shri Ramakrishna’s Birthday 03/26 Purnima Shri Krishna Dol Yatra, Holi, Gauranga Mahaprabhu Avirbhav Phalgun Krishna: 03/31 Pancami Shri Krishna Pancama Dol Yatra 04/01 Shashthi Skanda Shashthi 04/03 Ashthami Shri Sitalashtami 04/05 Ekadashi Upavas 04/07 Trayodashi Madhu Krishna Trayodashi Caitra Shukla: 04/10 Pratipad Vasanti Durga Devi Navaratri Vrat 04/15 Pancami Sat Pancami Vrat 04/16 Shashthi Shri Vasanti Durga -

Vikram Samvat 2076-77 • 2020

Vikram Samvat 2076-77 • 2020 Shri Vikari and Shri Shaarvari Nama Phone: (219) 756-1111 • [email protected] www.bharatiyatemple-nwindiana.org Vikram Samvat 2076-77 • 2020 Shri Vikari and Shri Shaarvari Nama Phone: (219) 756-1111 • [email protected] 8605 Merrillville Road • Merrillville, IN 46410 www.bharatiyatemple-nwindiana.org VIKARI PUSHYA - MAGHA AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PUSHYA - MAGHA AYANA: UTTARASUNDAY, RITU: SHISHIRA MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY DHANUSH – MAKARASATURDAY, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY -

Shani on the Web: Virality and Vitality in Digital Popular Hinduism

religions Article Shani on the Web: Virality and Vitality in Digital Popular Hinduism Varuni Bhatia School of Arts and Sciences, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560100, India; [email protected] Received: 10 August 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 6 September 2020 Abstract: What do god posters circulating online tell us about the practice of popular Hinduism in the age of digital mediatization? The article seeks to address the question by exploring images and god posters dedicated to the planetary deity Shani on Web 2.0. The article tracks Shani’s presence on a range of online platforms—from the religion and culture pages of newspapers to YouTube videos and social media platforms. Using Shani’s presence on the Web as a case study, the article argues that content drawn from popular Hinduism, dealing with astrology, ritual, religious vows and observances, form a significant and substantial aspect of online Hinduism. The article draws attention to the specific affordances of Web 2.0 to radically rethink what engaging with the sacred object in a virtual realm may entail. In doing so, it indicates what the future of Hindu religiosity may look like. Keywords: digital Hinduism; god posters; Shani; Hindu images; Hinduism and mediatization The power of digital media impinges on everyday life in contemporary times with ever-increasing scope and intensity. The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic has brought this fact into sharper relief than, perhaps, ever before. Needless to say, this enhanced digitality has also permeated the sphere of religion and religious rituals. How different religions reformulate ritual practices in the light of the pandemic and the theological and doctrinal implications of such reformulations is a topic for a different discussion. -

Book-3-Durga-Puja FINAL

BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA NEW AGE PUROHIT DARPAN! Bd¤¢eL f¤f¤−l¡¢qa−l¡¢qa cfÑZ! Book 3 DURGA PUJA dugÑA pUjA Purohit (priests) Kanai L. Mukherjee – Bibhas Bandyopadhyay Editor Aloka Chakravarty Publishers Association of Grandparents of Indian Immigrants, USA POBox 50032, Nashvillle, TN 37205 ([email protected]) Distributor Eagle Book Bindery Cedar Rapids. IA 52405 Fourth Edition i BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA LIST OF AUDIOS WITH PAGE REFERENCES Play audio by Control+Click on the link: www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga Audio Pages Titles Links 1 13 Preliminaries http://www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-01- Preliminaries-p-13.mp3 2 66 Bodhan- http://www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-02- Saptami Bodhan-Saptami-p65.mp3 3 118 Mahasthami- http://www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-03- Sandhi Mahastami-Sandhi-p117.mp3 4 144 Mahanabami- http:/www.agiivideo.com/books/audio/durga/Audio-04- Dashami Mahanavami-Conclusion-p144.mp3 Video: Prayers and Songs (Page 182) http://www.agiivideo.com/books/video/durga/Durga-stob-mpeg2.mp4 i BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA Global Communication Dilip Som Amitabha Chakrabarti Art work Monidipa Basu Tara Chattoraj Book 3 ii BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA DURGA PUJA dugÑA pUjA Purohit (priests) Kanai L. Mukherjee – Bibhas Bandyopadhyay Editor Aloka Chakravarty Publishers Association of Grandparents of Indian Immigrants, USA POBox 50032, Nashvillle, TN 37205 ([email protected]) Distributor Eagle Book Bindery Cedar Rapids. IA 52405 Fourth Edition iii BOOK 3: DURGA PUJA sîÑEdbmyIQ EdbIQ sîÑErAg vyAphAmÚ| bREþS ib>·u nimtAQ pRNmAim sdA iSbAmÚ|| ibåibåibåÉÉÉÙÛAQ ibåYinlyAQ idbYÙÛAn inbAisnIm| EJAignIQ EJAgjnnIQ ci&kAQ pRNmAmYhmÚÚÚ||||||Ú Sarbadebamayim Devim sarbaroga bhayapaham| Brahmesha Vishnu namitam pranamami sada Shivam || Vindhyastham vindyanilayam divyasthan nibasinim | Joginim jogajananim Chandikam pranamamyaham || Goddess of all Gods, who removes the fear of all diseases Worshipped by Brahma, Vishnu and Maheshwar; I bow to you .with reverence. -

Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Anthropology - Dissertations Affairs 12-2011 Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition Jishnu Shankar Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Shankar, Jishnu, "Aghoreshwar Bhagawan Ram and the Aghor Tradition" (2011). Anthropology - Dissertations. 93. https://surface.syr.edu/ant_etd/93 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Aghoreshwar Mahaprabhu Baba Bhagawan Ram Ji, a well-established saint of the holy city of Varanasi in north India, initiated many changes into the erstwhile Aghor tradition of ascetics in India. This tradition is regarded as an ancient system of spiritual or mystical knowledge by its practitioners and at least some of the practices followed in this tradition can certainly be traced back at least to the time of the Buddha. Over the course of the centuries practitioners of this tradition have interacted with groups of other mystical traditions, exchanging ideas and practices so that both parties in the exchange appear to have been influenced by the other. Naturally, such an interaction between groups can lead to difficulty in determining a clear course of development of the tradition. In this dissertation I bring together micro-history, hagiography, folklore, religious and comparative studies together in an attempt to understand how this modern day religious-spiritual tradition has been shaped by the past and the role religion has to play in modern life, if only with reference to a single case study. -

Sixty-Four Yoginis Dr Suruchi Pande

Sixty-Four Yoginis Dr Suruchi Pande oginis are holy women with yogic unmanifested sound, logos, and she creates the Ypowers or female attendants of Shiva or universe. Durga. Commonly it is believed that eight • Vaishnavi gives the universe a definite yoginis exist, namely Mangala, Pingala, Dhanya, shape. Bhramari, Bhadrika, Ulka, Siddhi, and Sankata. • Maheshvari gives individuality to all cre- They are also perceived as divinities constituted ated beings. by eight groups of letters of the alphabets. • Kaumari bestows the force of aspirations. The philosophy of the concept of yogini is • Varahi is the power of assimilation and based on the concept of Sapta Matrikas, seven enjoyment. Mother goddesses. These seven goddesses sym- • Aindri or Indrani is the immense power bolise the motherly aspect and have a logical, es- that destroys whatever opposes the cosmic law. oteric, and conceptual sequence. Sometimes the • Chamunda is the power of spiritual Sapta Matrikas are portrayed in a deeper philo- awakening. sophical conceptual meaning with the eight div- Sixty-four yoginis symbolise the multiplica- inities involved in the creation of universe and its tion of these values. The symbology involves ref- various integral life forms in a serial logical order. erences to sixteen kalas or phases that are consti- • Brahmi or Brahmani represents the tuted by the mind, five gross elements, and ten sense organs. The moon has sixteen phases out IMAGE: HTTP://REDISCOVERYPROJECT.COM / CHAUSATH-YOGINI-MANDIR, MITAWALI MITAWALI / CHAUSATH-YOGINI-MANDIR, IMAGE: HTTP://REDISCOVERYPROJECT.COM Dr Suruchi Pande is a Vice Chairperson, Ela Foun- of which fifteen are visible and one is invisible. -

Infallible VEDIC REMEDIES (Mantras for Common Problems) INFALLIBLE VEDIC REMEDIES (Mantras for Common Problems)

INfALLIBLE VEDIC REMEDIES (Mantras for Common Problems) _ INFALLIBLE VEDIC REMEDIES (Mantras for Common Problems) Swami Shantananda Puri Parvathamma C.P. Subbaraju Setty Charitable Trust # 13/8, Pampa Mahakavi Road Shankarapuram, Bangalore - 560 004 e-mail : [email protected] Ph : 2670 8186 / 2670 9026 INFALLIBLE VEDIC REMEDIES (MANTRAS FOR COMMON PROBLEMS) Author : Sri Swami Shantananda Puri © Publisher : Parvathamma C.P. Subbaraju Setty Charitable Trust 13/8, PMK Road Bangalore - 560 004. First Edition : September 2005 Enlarged Edition : November 2008 Cover Page design Type Setting & Printing : Omkar Offset Printers 1st Main Road, New Tharagupet Bangalore - 560 002 Ph : 26708186, 26709026. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.omkarprinters.com ii SAMARPAN This book is dedicated with veneration to the Lotus Feet of my revered Guru Swami Purushottamanandaji of Vasishtha Guha, U.P., Himalayas, but for whose infinite Compassion I would not have been able to formulate my thoughts and put them down in this book and to the welfare of Suffering Humanity. – Swami Shantananda Puri iii iv Inside Samarpan iii Introduction 1 Mantras for Common Problems : 1. For ensuring supply of food 32 2. For all physical and mental diseases 34 3. For improving intelligence, self confidence, fearlessness etc. 36 4. For removal of all diseases 38 5. For all heart diseases including hypertension (B.P) 40 6. For all eye diseases involving cataract, glaucoma, retina etc. 42 7. For cure from all types of fevers and animal bites including snake bites and insect bites. 46 8. A healing prayer to deal with diseases 48 v Inside 9. Mantra from Holy Japuji Saheb for healing diseases and invoking the grace of God.