Unit 9: Corporate Recovery in Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vehicle Owners Clubs

V765/1 List of Vehicle Owners Clubs N.B. The information contained in this booklet was correct at the time of going to print. The most up to date version is available on the internet website: www.gov.uk/vehicle-registration/old-vehicles 8/21 V765 scheme How to register your vehicle under its original registration number: a. Applications must be submitted on form V765 and signed by the keeper of the vehicle agreeing to the terms and conditions of the V765 scheme. A V55/5 should also be filled in and a recent photograph of the vehicle confirming it as a complete entity must be included. A FEE IS NOT APPLICABLE as the vehicle is being re-registered and is not applying for first registration. b. The application must have a V765 form signed, stamped and approved by the relevant vehicle owners/enthusiasts club (for their make/type), shown on the ‘List of Vehicle Owners Clubs’ (V765/1). The club may charge a fee to process the application. c. Evidence MUST be presented with the application to link the registration number to the vehicle. Acceptable forms of evidence include:- • The original old style logbook (RF60/VE60). • Archive/Library records displaying the registration number and the chassis number authorised by the archivist clearly defining where the material was taken from. • Other pre 1983 documentary evidence linking the chassis and the registration number to the vehicle. If successful, this registration number will be allocated on a non-transferable basis. How to tax the vehicle If your application is successful, on receipt of your V5C you should apply to tax at the Post Office® in the usual way. -

Universal Joints

GKN Driveline Rösrath GKN Driveline Stockholm GKN Service International GmbH GKN Driveline Service Scandinavia AB Nußbaumweg 19-21 P.O. Box 3100, Stensätravägen 9 Universal Joints D-51503 Rösrath SE-127 03 Skärholmen Fon: ++ 49 - 22 05 - 806- 0 Fon: ++ 46 8 6039700 Edition 2005 / 2006 Fax: ++ 49 - 22 05 - 806 - 204 Fax: ++ 46 8 6039701 GKN Driveline Barcelona GKN Driveline Carrières Pol. Ind Can Salvatella GKN Glenco SAS Avda. Arrahona, 54 170 rue Léonard de Vinci E-08210 Barberá del Vallés (Barcelona) F-78955 Carrières sous Poissy Almacén/Warehouse: Fon: ++ 33 1 30 06 84 00 Fon: ++ 34 93 718 40 15 Fax: ++ 33 1 30 06 84 01 Fax: ++ 34 93 729 54 14 Oficina/Office: Fon: ++ 34 93 718 64 85 GKN Driveline Minworth Fax: ++ 34 93 729 47 59 GKN Driveline Service Limited Unit 5, Kingsbury Business Park Kingsbury Road GKN Driveline Amsterdam Minworth GKN Service Benelux B.V. Birmingham Haarlemmerstraatweg 155-159 GB-B76 9DL NL-1165 MK Halfweg Fon: ++ 44 121 313 1661 Nederland Fax: ++ 44 121 313 2074 Fon: ++ 31-20-40 70 207 Fax: ++ 31-20-40 70 227 GKN Driveline Leek GKN Driveline Service Limited GKN Driveline Brussel Higher Woodcroft GKN Service Benelux B.V. Leek 410, rue Emile Pathéstraat Staffordshire B-1190 Brussel - Bruxelles GB-ST13 5QF Fon: ++ 32-2 334 9880 Fon: ++ 44 1538 384278 Fax: ++ 32-2 334 9892 Fax: ++ 44 1538 371265 ervices 07/2005 S GKN Driveline Milano GKN Driveline Wien Uni-Cardan Italia S.p.A. GKN Service Austria GmbH Via G. Ferraris, 125 Slamastraße 32 I-20021 Ospiate di Bollate (MI) Postfach 36A Fon: ++ 39 02 38338.1 A-1230 Wien Fax: ++ 39 02 33301030 Fon: ++ 43 1 616 38 80 Fax: ++ 43 1 616 38 28 Copyright: GKN Industrial & Distribution GB General Information 1. -

SATURDAY 19Th

HAZLE MEADOWS AUCTION CENTRE, LEDBURY HR8 2LP The first annual collective sale of VINTAGE, CLASSIC AND LATER COMMERCIALS, PLANT, TRACTORS, SPARES, MODELS, LITERATURE SATURDAY 19th MAY- 10AM Viewing 18th May 2-5pm and morning of sale Live and Online VIA www.easyliveauctions.com 5% Buyers premium +VAT Caterer in attendance Newmarket House, Market Street, Ledbury.Herefordshire. HR8 2AQ. Tel: 01531 631122. Fax: 01531 631818 Email: [email protected] CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. All prospective purchasers to register to bid and give in their name, address and telephone number, in default of which the lot or lots purchased may be immediately put up again and re-sold 2. The highest bidder to be the buyer. If any dispute arises regarding any bidding the Lot, at the sole discretion of the auctioneers, to be put up and sold again. 3. The bidding to be regulated by the auctioneer. 4. In the case of Lots upon which there is a reserve, the auctioneer shall have the right to bid on behalf of the Vendor. 5. No Lots to be transferable and all accounts to be settled at the close of the sale. 6. The lots to be taken away whether genuine and authentic or not, with all faults and errors of every description and to be at the risk of the purchaser immediately after the fall of the hammer but must be paid for in full before the property in the goods passes to the buyer. The auctioneer will not hold himself responsible for the incorrect description or authenticity of or any fault or defect in any lot and makes no warranty. -

CORGI 2007 Catalogue

TRACKSIDE FEATURE 25/9/06 16:57 Page 1 Bringing model rail layouts to life, Corgi’s 2007 Trackside range has a great selection of new tools such as the Vauxhall HA Van, Harrington Horsebox and the Morris 1000 Van. Perfectly complementing the ‘OO’ range and in response to popular demand, Corgi have also launched an impressive range of 1:76 scale model cars. The Classic Ford Anglia 105E, Morris Minor 1000 and Vauxhall Viva HA are all legends of the road and deserve to be remembered as key vehicles of the era. Trackside.......... The Best of British 126 Trackside January - December 2007 TRACKSIDE FEATURE 25/9/06 17:12 Page 2 127 www.corgi.co.uk TRACKSIDE_PAGES 26/9/06 18:57 Page 1 SCALE 1:76 NON LIMITED MODEL NO DG201005 MODEL NO DG200006 MODEL NAME MORRIS LD MODEL NAME FORD TRANSIT OPERATOR BRS OPERATOR EVENING NEWS RELEASE MARCH RELEASE JULY BARCODE 080577803525 BARCODE 080577803648 The Morris Commercial LD 1-ton van with its early ‘beehive’ grille began production in If one vehicle revolutionised the van market, it was the Ford Transit, launched in 1953. Frontal styling was revised from 1955 and the vans were badged as Austin or 1965, with its V4 petrol engine and two wheelbase options. It was suitable for a vast MODEL NO DG203005 Morris. A 1.5-ton version was added and production continued until 1967. range of special bodywork and Transit production continued until January 1971. MODEL NAME BEDFORD CA OPERATOR HOLLAND TOFFEE RELEASE JANUARY BARCODE 080577803440 Launched in 1952 the Bedford CA 10/12 cwt van featured semi-forward control, a 1.5 litre petrol engine and sliding doors. -

2008 Advanced Vehicle Technology Analysis and Evaluation Activities

annual progress report 2008V EHICLE T ECHNOLOGIES P ROGRAM ADVANCED VEHICLE TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION ACTIVITIES AND HEAVY VEHICLE SYSTEMS OPTIMIZATION PROGRAM A Strong Energy Portfolio for a Strong America Energy efficiency and clean, renewable energy will mean a stronger economy, a cleaner environment, and greater energy independence for America. Working with a wide array of state, community, industry, and university partners, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy invests in a diverse portfolio of energy technologies. For more information contact: EERE Information Center 1-877-EERE-INF (1-877-337-3463) www.eere.energy.gov U.S. Department of Energy Vehicle Technologies Program 1000 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20585-0121 FY 2008 Annual Progress Report for Advanced Vehicle Technology Analysis and Evaluation Activities and Heavy Vehicle Systems Optimization Program Submitted to: U.S. Department of Energy Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Vehicle Technologies Program Advanced Vehicle Technology Analysis and Evaluation Lee Slezak, Technology Manager FY 2008 Annual Report AVTAE Activities & HVSO Program ii AVTAE Activities & HVSO Program FY 2008 Annual Report CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................1 II. MODELING AND SIMULATION....................................................................................................9 A. PSAT Model Validation ...............................................................................................................9 -

Wva Models E11 Certificate No 19052/19055 Daf Truck .Daf

WVA MODELS E11 CERTIFICATE NO 19052/19055 DAF TRUCK .DAF PSV'S VOLVO,DENNIS,RENAULT TRUCKS, 19090 SEDDON ATKINSON 19463 RENAULT TRUCKS 19486 MERCEDES-BENZ 19494 MERCEDES-BENZ 19579/19580 MAN PSV'S 90R-02B01347/32769 19657 RENAULT TRUCK 19706 MAN PSV'S ,MERCEDES-BENZ 19713 MAN,MAN PSV'S 19888/19889 DAF, OPTARE 19935 RENAULT TRUCKS 19938 VOLVO 19068 DENNIS,HEULIEZ,VOLVO 19187 RENAULT TRUCKS 19488 MAN PSV'S,MAN, STEYR-DAIMLER -PUCH 19496 MAN PSV'S,MAN, STEYR-DAIMLER -PUCH 19581/19582 MAN PSV'S MERCEDES-BENZ,NEOPLAN,SETRA, 19699 VAN HOOL,VDL 90R-02B01347/32772 MAN PSV'S ,MERCEDES-BENZ,NEOPLAN,VDL 19707 WRIGHTBUS MERCEDES-BENZ,NEOPLAN, 19743/19755 SETRA, VAN HOOL 19824/19838 IVECO PSV 19847/19848 NEOPLAN,SETRA 19940 VOLVO 19015 DAF TRUCKS 19017/19997 SEDDON ATKINSON 19063/19064 DAF TRUCKS,DAF PSV'S BMC,DENNIS,ERF,SEDDON ATKINSON, 19071/19288 STEYR-DAIMLER-PUCH,VOLVO,IVECO 19091/19098 IVECO 19116/19119 ERF 19263/19343 IVECO 19365/19366 DAF TRUCKS,FODEN,SEDDON ATKINSON 19393 SCANIA,SCANIA PSV 19553/19554 ERF,IVECO 90R-02B01347/32771 19617/19618 DAF PSV'S,VAN HOOL 19716/19717 ERF,IVECO 19754 IVECO PSV,KAROSA,RECREO 19786 IVECO PSV,VAN HOOL 19879/19881 PEGASO,SEDDON ATKINSON 19890/19891 DAF TRUCKS,DAF PSV'S,VDL 19926 SCANIA 19932 SCANIA,SCANIA PSV 90R-02B01347/32771 ERF, SEDDON ATKINSON,STEYR-DIAMLER- 19939 PUCH,VOLVO 19036/19037/19035 DAF TRUCKS,FODEN,SEDDON ATKINSON 19039 DAF TRUCKS,FODEN ,SEDDON ATKINSON 19075 NEOPLAN,SCANIA 19099/19100 IVECO 19109/19110 IVECO 19235 IKARUS 19236 IKARUS 19246 STEYR-DAIMLER-PUCH 19256/19260 DAF TRUCK,DAF PSV'S,NEOPLAN,VDL -

Product Guide

Product Guide THERMOSET Halmatic Ltd A CD THERMOPLASTIC Hardy (M W) (Mercantile} Ltd C D MATERIALS Hercules Powder Co Ltd B C MATERIALS Hermetite Products Ltd AD Hoechst UK Ltd A C D D Epoxide A Honeywell-Atlas Ltd ABS A Ltd D Melamine formaldehyde B Huls (UK) Acrylics B A Phenol formaldehyde C Hysol Sterling Ltd Fluorocarbons (PCTFE) C Polyester D Imperial Chemical Industries Fluorocarbons (PTFE) D B C D E F Urea formaldehyde E Ltd A Polyacetals E Components & Materials Silicones F Insulating Polyamides (Nylon) F Ltd A C D Polycarbonates G Island Plastics Ltd A D Polypropylenes H Jacobson van den Berg & Co (UK) Ltd F Polystyrenes I Anchor Chemical Developments Ltd c KW Chemicals Ltd D Polyethylenes J Aquitane Organico (UK) Ltd A Kingsley & Keith (Chemicals} Ltd A C PVC K Arcode Ltd c Laporte-Synres Ltd B C D E Arinor Ltd D Mica & Micanite Supplies Ltd A C D F Ault & Wiborg Ltd D Micanite & Insulators Ltd A C D F ADI Plastics Ltd B Automobile Plastics Co Ltd A D Middlesex Oil & Chemical Works Ltd D F Albis Plastic Co (Great Britain) Ltd A I J K BASF United Kingdom Ltd B D Midland Silicones Ltd F Alpine Insulations Ltd I B & K Moulds Ltd AD Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Ansor'ite Manufacturing Co F BIP Chemicals Ltd B C E Co Ltd AD Archway Plastics Ltd A B H I BP Chemicals International Ltd B C D E Mining & Chemical Products Ltd E Arcode Ltd A I J K Bakelite Xylonite Ltd (BXL) A B C D Mitchell (W A) & Smith Ltd C D Associated Resin Compounds I J Bayer Chemicals Ltd A D Mosses & Mitchell Ltd A C BASF United Kingdom Ltd A F I J Berk Ltd -

Dash Clusters ‐ Dashboard Instrument Clusters

• SAME DAY FREE COLLECTION • NEXT DAY DELIVERY • 12 MONTH WARRANTY • NATIONWIDE SERVICE • “The Truck Specialist” "Alliance Electronics helping to keep your vehicles on the road since 1993" Alliance Electronics supplies a wide range of new & Remanufactured Electrical and Electronic parts that are used throughout the Commercial Vehicle Industry. Our parts will give you peace of mind that you have a quality remanufactured part supplied with a 12 month warranty and which will minimise downtime and maximise cost savings. Alliance Electronics Remanufacture just about any electrical or electronic part on a Commercial Vehicle. We will also collect any of your own parts free of charge with the aim to turn them around Remanufactured the following day. (mainland UK only) You can Phone, Fax, Email us or fill in an online collection form and we will organise a free collection of your parts from anywhere in mainland UK. Exclusive UK Distributor to the Commercial Vehicle Industry Alliance Electronics is the Exclusive UK Distributor for Powervamp Battery Jump‐starter packs for the automotive industry SEE PAGE 13 2014 Alliance Electronics Ltd celebrates its 21st birthday We would like to take this opportunity to thank all our customers that have helped make Alliance Electronics the Commercial Vehicle Electronics and Electrical Parts Specialist it is today. Thanks and here’s to the next 21 years. • SAME DAY FREE COLLECTION • NEXT DAY DELIVERY • 12 MONTH WARRANTY • NATIONWIDE SERVICE • “The Truck Specialist” Dash Clusters ‐ Dashboard Instrument Clusters -

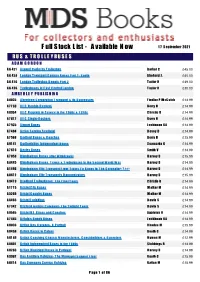

Full Stock List

Full Stock List - Available Now 17 September 2021 BUS & TROLLEYBUSES ADAM GORDON https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/16453/s/around-derby-by-trolleybus/ AG421 Around Derby by Trolleybus Barker C £45.00 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/buses-trolleybuses/london-transport-country-buses-part-1-south.html AG428 London Transport Country Buses Part 1: South Akehurst L £40.00 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/15354/s/london-trolleybus-depots-part-2/ AG416 London Trolleybus Depots Part 2 Taylor H £39.00 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/trolleybuses-in-east-central-london.html AG426 Trolleybuses in East Central London Taylor H £30.00 AMBERLEY PUBLISHING https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/14856/s/Aberdeen%20Corporation%20Transport%20&%20its%20Successors/ A8035 Aberdeen Corporation Transport & its Successors Findlay P/McCutch £14.99 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/15289/s/aec-double-deckers/ A7759 AEC Double-Deckers Berry H £14.99 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/15571/s/aec-regents-in-service-in-the-1960s-1970s/ A8954 AEC Regents in Service in the 1960s & 1970s Christie D £14.99 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/14240/s/AEC%20Single-Deckers/ A7672 AEC Single-Deckers Berry H £14.99 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/14335/s/Airport%20Buses/ A7935 Airport Buses Jenkinson KA £14.99 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/catalog/product/view/id/15285/s/arriva-serving-scotland/ A7404 Arriva Serving Scotland Devoy D £14.99 https://www.mdsbooks.co.uk/bedford-buses-coaches.html -

12 071 June A

Created in TESTS BY MAKE AND YEAR OF MANUFACTURE for VEHICLE HGV upto 1995 YEAR of MANUFACTURE Make . AEC . ALBION . BEDFORD . DAF . DAF . DAF . DAF . DAF . DAF . DAF . DODGE . FORD . FORD . FORD . FORD . IVECO . IVECO FORD . LEYLAND . LEYLAND DAF . LEYLAND ROADRUNNER . MAN . MAN . MAN . MAN/ERF . MAN/ERF . MERCEDES . MERCEDES . MERCEDES . MERCEDES . MERCEDES BENZ . RENAULT . RENAULT . RENAULT DODGE . SCANIA . SCANIA . SCANIA . SCANIA . SEDDON ATKINSON . VOLKESWAGON . VOLVO . VOLVO . VOLVO 1884 FORD 1901 ERF 1904 MERCEDES BENZ 1909 MERCEDES BENZ 1938 BEDFORD 1944 MACK 1951 BEDFORD 1953 BEDFORD 1953 COMMER 1954 CITROEN 1954 AUSTIN 1954 BEDFORD 1957 FORD 1957 BEDFORD 1958 SIMCA-UNIC 1960 FORD 1960 FODEN 1960 BEDFORD 1960 FODEN 1960 ERF 1960 FORD 1960 MUSTAND 1960 FORD 1961 BEDFORD 1961 BRISTOL 1961 FODEN 1961 MERCEDES 1961 MERCEDES BENZ 1961 SEDDON 1961 AEC 1961 DENNIS 1961 A.E.C. 1961 FORD 1961 ATKINSON 1961 ERF 1961 FODEN 1961 MERCEDES 1961 MORRIS 1961 BEDFORD 1961 BEDFORD 1961 FORD 1962 FORD 1962 MORRIS 1962 BEDFORD 1962 DENNIS 1962 SCAMMELL 1962 MORRIS 1962 FODEN 1962 FODEN 1962 FODEN 1962 FODEN 1963 AEC 1963 ALBION 1963 BEDFORD 1963 BEDFORD 1963 FODEN 1963 FODEN 1963 BEDFORD 1963 ERF 1963 SEDDON ATKINSON 1963 BEDFORD 1963 BEDFORD 1963 ERF 1963 SCAMMEL 1963 DODGE 1963 FORD 1963 AUSTIN 1963 COMMER 1964 AEC MILITANT 1964 BEDFORD 1964 LEYLAND 1964 FORD 1964 ERF 1964 FORD 1964 BEDFORD 1964 BEDFORD 1964 FORD 1964 ATKINSON 1964 MORRIS 1964 FODEN 1964 FORD 1964 LEYLAND DAF 1964 AEC 1964 AUSTIN 1964 COMMER 1964 ERF 1964 FORD 1964 FORD 1965 A.E.C. -

MAN SE Annual Report 2016

The MAN Group is one of Europe’s leading players in the engine, commercial vehicle, and mechanical engineering industries. As a supplier of trucks, buses, vans, diesel engines, turbomachinery, and special gear units, we hold leading positions in all our markets. II MAN AT A GLANCE 2016 ORDER INTAKE ON A LEVEL WITH THE PREVIOUS YEAR 14.4 € billion [ 2015: €14.4 billion] SALES REVENUE SLIGHTLY BELOW THE PREVIOUS YEAR 13.6 € billion [ 2015: €13.7 billion] SIGNIFICANT IMPROVEMENT IN OPERATING PROFIT 204 € million [ 2015: €92 million] SIGNIFICANT IMPROVEMENT IN OPERATING RETURN ON SALES 1.5 percent [ 2015: 0.7%] BREAK-EVEN NET CASH FLOW 0 € billion [ 2015: €0.5 billion] III Group key figures (IFRSs) Change € million 2016 2015 in % Order intake 14,357 14,381 0 Germany 3,677 3,486 5 Other countries 10,680 10,895 – 2 Sales revenue 13,564 13,702 – 1 Germany 3,273 3,252 1 Other countries 10,290 10,449 – 2 Order backlog 1 5,641 6,037 – 7 Headcount 1 53,824 55,030 – 2 Change Income statement € million Operating profit before special items 2 417 277 140 Special items 2 – 213 – 185 – 28 Operating profit 204 92 112 Operating return on sales (%) 1.5 0.7 0.8 Earnings before tax from continuing operations (EBT) 49 95 – 46 Profit/loss after tax – 7 150 – 156 Balance sheet Total assets 1 19,438 18,110 1,327 Total equity 1 5,850 5,565 285 Equity ratio (%) 1 30.1 30.7 – 0.6 Net financial debt 1 – 1,875 – 1,311 – 564 Cash and cash equivalents 1 796 779 17 Cash flow Net cash provided by operating activities 833 1,162 – 329 Net cash used in investing activities attributable to operating activities – 831 – 667 – 164 Net cash flow 2 495 – 493 Change Shares in € Earnings per share from continuing operations in € – 0.12 1.02 – 1.14 Annual cash compensation payment/guaranteed dividend per share in € 3 3.07 3.07 – 1 As of December 31, 2016, vs. -

Ricardo Study on Cost Analysis of V2I Deployment

Cost Analysis of V2I Deployment Final Report ___________________________________________________ Report for 5GAA 7720475 ED 13276 | Issue Number 5 | Date 11/08/2020 Ricardo Energy & Environment Cost Analysis of V2I Deployment | i Customer: Contact: 5G Automotive Association E.V. Tom Nokes Ricardo Energy & Environment Customer reference: 30 Eastbourne Terrace, London, W2 6LA, United Kingdom 7720475 t: +44 (0) 1235 75 3102 Confidentiality, copyright & reproduction: e: [email protected] This report is the Copyright of Ricardo Energy & Ricardo is certificated to ISO9001, ISO14001 Environment, a trading name of Ricardo-AEA Ltd and OHSAS18001 and has been prepared by Ricardo Energy & Environment under contract to 5GAA for Authors: Analysis of V2X deployment cost of 11p RSU vs C-V2X (Uu/PC5), 06/01/2020. The contents of Tom Nokes, Ben Baxter, Harry Scammell, this report may not be reproduced in whole or in Denis Naberezhnykh (Ricardo), Leonardo part, nor passed to any organisation or person Provvedi (Roke) without the specific prior written permission of the Commercial Manager at Ricardo Energy & Approved By: Environment. Ricardo Energy & Environment accepts no liability whatsoever to any third party Denis Naberezhnykh for any loss or damage arising from any interpretation or use of the information contained Date: in this report, or reliance on any views expressed 11 August 2020 therein, other than the liability that is agreed in the said contract. Ricardo Energy & Environment reference: Ref: ED13276- Issue Number 5 Ricardo Confidential Ref: Ricardo/ED13276/Issue Number 5 Ricardo Energy & Environment Cost Analysis of V2I Deployment | 1 Table of contents 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 2 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Definitions .........................................................................................................................