Télécharger La Page En Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Pond to Pro: Hockey As a Symbol of Canadian National Identity

From Pond to Pro: Hockey as a Symbol of Canadian National Identity by Alison Bell, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology and Anthropology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 19 April, 2007 © copyright 2007 Alison Bell Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-26936-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-26936-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Team Team Philadelphia Quakers Montreal Wanderers 1991 San

17/ 18/ 19/ 20/ 21/ 22/ 23/ 24/ 25/ 26/ 27/ 28/ 29/ 30/ 31/ 32/ 33/ 34/ 35/ 36/ 37/ 38/ 39/ 40/ 41/ 42/ 43/ 44/ 45/ 46/ 47/ 48/ 49/ 50/ 51/ 52/ 53/ 54/ 55/ 56/ 57/ 58/ 59/ 60/ 61/ 62/ 63/ 64/ 65/ 66/ 67/ 68/ 69/ 70/ 71/ 72/ 73/ 74/ 75/ 76/ 77/ 78/ 79/ 80/ 81/ 82/ 83/ 84/ 85/ 86/ 87/ 88/ 89/ 90/ 91/ 92/ 93/ 94/ 95/ 96/ 97/ 98/ 99/ 00/ 01/ 02/ 03/ 04/ 05/ 06/ 07/ 08/ 09/ 10/ 11/ 12/ 13/ 14/ 15/ 16/ 17/ 18/ 19/ 20/ 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Team 1917 Montreal Canadiens Montreal Canadiens 1917-1919 1919 - 1927 Toronto Arenas/St. Patricks/Maple Leafs Arenas Toronto St. Patricks 1927 Toronto Maple Leafs 1924 Boston Bruin Boston Bruins 1926 Chicago Blackhawks Chicago Blackhawks 1926 New York Rangers New York Rangers 1926-1930 Detroit 1930-1932 Detroit Cougars/Falcons/Red Wings Cougars Falcons 1932 Detroit Red Wings 1967 Los Angeles Kings Los Angeles Kings 1967 Philadelphia Flyers Philadelphia Flyers 1967 Pittsburgh Penguins Pittsburgh Penguins 1967 St. -

Sports Rates 2 Indiana 5S for in Big 10 Cellar Lt

THI DITRf'T TIMES I H 4MI 14-C * > ", Jan. 1945 Three Winqs Go to Hawks For Siebert Bob Tales Sports Rates 2 Indiana 5s FOR In Big 10 Cellar Lt. Davey Nelson DETROITERS SPLASH GREAT LAKES boys (left right) High " By 808 MURPHY to Four Detroit to Gerald Asselin from free styler, and Ray Mondro, high school and Wayne W ¦ g Goes Hawaii St. ( lair Recreation (enter; Ned Diefendorf, former Uni- University breast stroke star, will be among the aces Sporta Editor x »ersity of Michigan diver; Pylkas, 1-akes sends light shadow By LEO MACDONELL Arnold Northwestern Great against U. M. Saturday at Ann Arbor. Let’s do a little boxing and see what’s going on (jg.) Dawy Nelson, former Lt. at University of Michigan football various places. star, now In naval intelligence, is For one thing, here is some- on his way to Pearl Harbor. A thing bordering on basketball flier, after returning from an as- sacrilege. Dave MacMillan, as- signment in the Aleutians, Lt. sistant coach and head scout of Nelson, transferred to intelligence the Minnesota cagesters, says the and received his Pacific assign- worst two teams in the Big Ten * * - and jmM i, ment after a this season are Indiana course In Purdue. Washington. For a man to have made a Having spent statement like this in years past Y something like would have meant a fast trip to 50 minutes In the pogey with a police escort. «*? M the penalty t Wbox. Frank MacMillan says Ohio State, I 2A <R«D Kane of lowa find Illinois rate in the first I \ the Indianapo- brae gr t with Northwestern, Mich- lis Capitols igan and Wisconsin in the second ¦K y (IVtroit farm group. -

Nhl Morning Skate – Feb. 26, 2019 2019 Nhl Trade Deadline

NHL MORNING SKATE – FEB. 26, 2019 2019 NHL TRADE DEADLINE RECAP Teams made 20 trades involving 32 players on Monday prior to the 2019 NHL Trade Deadline. A few highlights: * The Golden Knights acquired forwards Mark Stone and Tobias Lindberg from the Senators in exchange for defenseman Erik Brannstrom, forward Oscar Lindberg and the Stars' second- round pick in the 2020 NHL Draft (previously acquired). * The Predators acquired forward Wayne Simmonds from the Flyers in exchange for forward Ryan Hartman and a conditional pick in the 2020 NHL Draft. * The Jets acquired forward Kevin Hayes from the Rangers in exchange for forward Brendan Lemieux, a first-round pick in the 2019 Draft (conditional) and a conditional pick in 2022. * The Predators acquired forward Mikael Granlund from the Wild in exchange for forward Kevin Fiala. * The Bruins acquired forward Marcus Johansson from the Devils in exchange for a second- round pick in the 2019 NHL Draft and a fourth-round pick in 2020. Click here for more information. MONDAY’S RESULTS Home Team in Caps TORONTO 5, Buffalo 3 NEW JERSEY 2, Montreal 1 TAMPA BAY 4, Los Angeles 3 (SO) NASHVILLE 3, Edmonton 2 (SO) Florida 4, COLORADO 3 (OT) VANCOUVER 4, Anaheim 0 LUONGO PASSES BELFOUR FOR THIRD PLACE ON ALL-TIME WINS LIST Panthers goaltender Roberto Luongo made 36 saves through regulation and overtime to earn the 485th regular-season win of his NHL career and pass Ed Belfour (484) for sole possession of third place on the League’s all-time list. * The three winningest goaltenders in NHL history are now all Quebec-born. -

1965-66 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1965-66 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Toe Blake 2 Gump Worsley 3 Jacques Laperriere 4 Jean Guy Talbot 5 Ted Harris 6 Jean Beliveau 7 Dick Duff 8 Claude Provost 9 Red Berenson 10 John Ferguson 11 Punch Imlach 12 Terry Sawchuk 13 Bob Baun 14 Kent Douglas 15 Red Kelly 16 Jim Pappin 17 Dave Keon 18 Bob Pulford 19 George Armstrong 20 Orland Kurtenbach 21 Ed Giacomin 22 Harry Howell 23 Rod Seiling 24 Mike McMahon 25 Jean Ratelle 26 Doug Robinson 27 Vic Hadfield 28 Garry Peters 29 Don Marshall 30 Bill Hicke 31 Gerry Cheevers 32 Leo Boivin 33 Albert Langlois 34 Murray Oliver 35 Tom Williams 36 Ron Schock 37 Ed Westfall 38 Gary Dornhoefer 39 Bob Dillabough 40 Paul Popeil 41 Sid Abel 42 Roger Crozier Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Doug Barkley 44 Bill Gadsby 45 Bryan Watson 46 Bob McCord 47 Alex Delvecchio 48 Andy Bathgate 49 Norm Ullman 50 Ab McDonald 51 Paul Henderson 52 Pit Martin 53 Billy Harris 54 Billy Reay 55 Glenn Hall 56 Pierre Pilote 57 Al MacNeil 58 Camille Henry 59 Bobby Hull 60 Stan Mikita 61 Ken Wharram 62 Bill Hay 63 Fred Stanfield 64 Dennis Hull 65 Ken Hodge 66 Checklist 1-66 67 Charlie Hodge 68 Terry Harper 69 J.C Tremblay 70 Bobby Rousseau 71 Henri Richard 72 Dave Balon 73 Ralph Backstrom 74 Jim Roberts 75 Claude LaRose 76 Yvan Cournoyer (misspelled as Yvon on card) 77 Johnny Bower 78 Carl Brewer 79 Tim Horton 80 Marcel Pronovost 81 Frank Mahovlich 82 Ron Ellis 83 Larry Jeffrey 84 Pete Stemkowski 85 Eddie Joyal 86 Mike Walton 87 George Sullivan 88 Don Simmons 89 Jim Neilson (misspelled as Nielson on card) -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 10, 2021 Mackinnon, MATTHEWS and Mcdavid VOTED HART TROPHY FINALISTS NEW YORK

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 10, 2021 MacKINNON, MATTHEWS AND McDAVID VOTED HART TROPHY FINALISTS NEW YORK (June 10, 2021) – Colorado Avalanche center Nathan MacKinnon, Toronto Maple Leafs center Auston Matthews and Edmonton Oilers center Connor McDavid are the three finalists for the 2020-21 Hart Memorial Trophy, awarded “to the player adjudged to be the most valuable to his team,” the National Hockey League announced today. Members of the Professional Hockey Writers Association submitted ballots for the Hart Trophy at the conclusion of the regular season, with the top three vote-getters designated as finalists. The winners of the 2021 NHL Awards presented by Bridgestone will be revealed during the Stanley Cup Semifinals and Stanley Cup Final, with exact dates, format and times to be announced. Following are the finalists for the Hart Trophy, in alphabetical order: Nathan MacKinnon, C, Colorado Avalanche MacKinnon placed fourth in the NHL with a career-high 1.35 points per game (20-45—65 in 48 GP) to propel the Avalanche’s top-ranked offense to the franchise’s third Presidents’ Trophy (also 1996-97 and 2000-01). MacKinnon finished among the League leaders in shots on goal (3rd; 206), power-play points (3rd; 25), assists (5th; 45), points (8th; 65) and power-play assists (t-10th; 17) despite missing eight of Colorado’s 56 contests. He did so on the strength of a career-best 15-game point streak from March 27 – April 28 (9-17—26), the longest by any player in 2020-21 as well as the longest by a member of the Avalanche since 2006-07 (Paul Stastny: 20 GP). -

Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 9 September 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 783016864] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of the History of Sport Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713672545 Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson To cite this Article Wilson, JJ(2005) 'Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War', International Journal of the History of Sport, 22: 3, 315 — 343 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09523360500048746 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360500048746 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

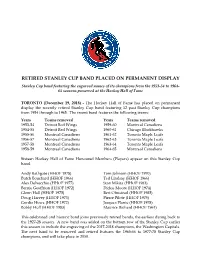

Retired Stanley Cup Band Placed on Permanent Display

RETIRED STANLEY CUP BAND PLACED ON PERMANENT DISPLAY Stanley Cup band featuring the engraved names of its champions from the 1953-54 to 1964- 65 seasons preserved at the Hockey Hall of Fame TORONTO (December 19, 2018) - The Hockey Hall of Fame has placed on permanent display the recently retired Stanley Cup band featuring 12 past Stanley Cup champions from 1954 through to 1965. The recent band features the following teams: Years Teams removed Years Teams removed 1953-54 Detroit Red Wings 1959-60 Montreal Canadiens 1954-55 Detroit Red Wings 1960-61 Chicago Blackhawks 1955-56 Montreal Canadiens 1961-62 Toronto Maple Leafs 1956-57 Montreal Canadiens 1962-63 Toronto Maple Leafs 1957-58 Montreal Canadiens 1963-64 Toronto Maple Leafs 1958-59 Montreal Canadiens 1964-65 Montreal Canadiens Sixteen Hockey Hall of Fame Honoured Members (Players) appear on this Stanley Cup band. Andy Bathgate (HHOF 1978) Tom Johnson (HHOF 1970) Butch Bouchard (HHOF 1966) Ted Lindsay (HHOF 1966) Alex Delvecchio (HHOF 1977) Stan Mikita (HHOF 1983) Bernie Geoffrion (HHOF 1972) Dickie Moore (HHOF 1974) Glenn Hall (HHOF 1975) Bert Olmstead (HHOF 1985) Doug Harvey (HHOF 1973) Pierre Pilote (HHOF 1975) Gordie Howe (HHOF 1972) Jacques Plante (HHOF 1978) Bobby Hull (HHOF 1983) Maurice Richard (HHOF 1961) This celebrated and historic band joins previously retired bands, the earliest dating back to the 1927-28 season. A new band was added on the bottom row of the Stanley Cup earlier this season to include the engraving of the 2017-2018 champions, the Washington Capitals. The next band to be removed and retired features the 1965-66 to 1977-78 Stanley Cup champions, and will take place in 2030. -

Vol.37 No.6 D'océanographie

ISSN 1195-8898 . CMOS Canadian Meteorological BULLETIN and Oceanographic Society SCMO La Société canadienne de météorologie et December / décembre 2009 Vol.37 No.6 d'océanographie Le réseau des stations automatiques pour les Olympiques ....from the President’s Desk Volume 37 No.6 December 2009 — décembre 2009 Friends and colleagues: Inside / En Bref In late October I presented the CMOS from the President’s desk Brief to the House of Allocution du président Commons Standing by/par Bill Crawford page 177 Committee on Finance at its public hearing in Cover page description Winnipeg. (The full text Description de la page couverture page 178 of this brief was published in our Highlights of Recent CMOS Meetings page 179 October Bulletin). Ron Correspondence / Correspondance page 179 Stewart accompanied me in this presentation. Articles He is a past president of CMOS and Head of the The Notoriously Unpredictable Monsoon Department of by Madhav Khandekar page 181 Environment and Geography at the The Future Role of the TV Weather Bill Crawford Presenter by Claire Martin page 182 CMOS President University of Manitoba. In the five minutes for Président de la SCMO Ocean Acidification by James Christian page 183 our talk we presented three requests for the federal government to consider in its The Interacting Scale of Ocean Dynamics next budget: Les échelles d’interaction de la dynamique océanique by/par D. Gilbert & P. Cummins page 185 1) Introduce measures to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions; Interview with Wendy Watson-Wright 2) Invest funds in the provision of science-based climate by Gordon McBean page 187 information; 3) Renew financial support for research into meteorology, On the future of operational forecasting oceanography, climate and ice science, especially in tools by Pierre Dubreuil page 189 Canada’s North, through independent, peer-reviewed projects managed by agencies such as CFCAS and Weather Services for the 2010 Winter NSERC. -

An Educational Experience

INTRODUCTION An Educational Experience In many countries, hockey is just a game, but to Canadians it’s a thread woven into the very fabric of our society. The Hockey Hall of Fame is a museum where participants and builders of the sport are honoured and the history of hockey is preserved. Through the Education Program, students can share in the glory of great moments on the ice that are now part of our Canadian culture. The Hockey Hall of Fame has used components of the sport to support educational core curriculum. The goal of this program is to provide an arena in which students can utilize critical thinking skills and experience hands-on interactive opportunities that will assure a successful and worthwhile field trip to the Hockey Hall of Fame. The contents of this the Education Program are recommended for Grades 6-9. Introduction Contents Curriculum Overview ……………………………………………………….… 2 Questions and Answers .............................................................................. 3 Teacher’s complimentary Voucher ............................................................ 5 Working Committee Members ................................................................... 5 Teacher’s Fieldtrip Checklist ..................................................................... 6 Map............................................................................................................... 6 Evaluation Form……………………............................................................. 7 Pre-visit Activity ....................................................................................... -

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

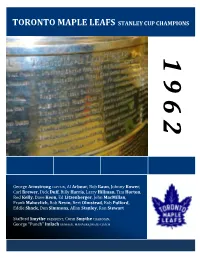

TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 6 2 George Armstrong CAPTAIN, Al Arbour, Bob Baun, Johnny Bower, Carl Brewer, Dick Duff, Billy Harris, Larry Hillman, Tim Horton, Red Kelly, Dave Keon, Ed Litzenberger, John MacMillan, Frank Mahovlich, Bob Nevin, Bert Olmstead, Bob Pulford, Eddie Shack, Don Simmons, Allan Stanley, Ron Stewart Stafford Smythe PRESIDENT, Conn Smythe CHAIRMAN, George “Punch” Imlach GENERAL MANAGER/HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1962 STANLEY CUP SEMI-FINAL 1 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 98 v. 3 CHICAGO BLACK HAWKS 75 GM FRANK J. SELKE, HC HECTOR ‘TOE’ BLAKE v. GM TOMMY IVAN, HC RUDY PILOUS BLACK HAWKS WIN SERIES IN 6 Tuesday, March 27 Thursday, March 29 CHICAGO 1 @ MONTREAL 2 CHICAGO 3 @ MONTREAL 4 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD NO SCORING 1. CHICAGO, Bobby Hull 1 (Bill Hay, Stan Mikita) 5:26 PPG 2. MONTREAL, Dickie Moore 2 (Bill Hicke, Ralph Backstrom) 15:10 PPG Penalties – Moore M 0:36, Horvath C 3:30, Wharram C Fontinato M (double minor) 6:04, Fontinato M 11:00, Béliveau M 14:56, Nesterenko C 17:15 Penalties – Evans C 1:06, Backstrom M 3:35, Moore M 8:26, Plante M (served by Berenson) 9:21, Wharram C 14:05, Fontinato M 17:37 SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING SECOND PERIOD 3. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.