Landscape and Dialectical Atavism in the Ruling Class PAPER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Barnes and the Nature of Authority

PETER BARNES AND THE NATURE OF AUTHORITY Liorah Anrie Golomb A thesis subnitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Study of Drarna in the University of Toronto @copyright by Liorah Anne Golomb 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliagraphiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington OttawaON K1AW Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à fa National Libmy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loaq distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distri'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. PETER BARNES AND THE NATURE OF AUTHORITY Liorah Anne Golomb Doctor of Philosophy, 1998 Graduate Centre for Study of Drama University of Toronto Peter Barnes, among the most theatrically-minded playwrights of the non-musical stage in England today, makes use of virtually every elernent of theatre: spectacle, music, dance, heightened speech, etc- He is daring, ambitious, and not always successful. -

The Humor of Red Noses by Peter

LAUGHING AT THE DEVIL: THE HUMOR OF RED NOSES BY PETER BARNES by PAULA JOSIE RODRIGUEZ, B.F.A. A THESIS IN THEATRE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Approved December, 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several people I would like to thank for their motivation and assistance throughout my graduate career at Texas Tech University. I wish to thank my thesis chairperson. Dr. Jonathan Marks for his encouragement, faith, and guidance through the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Professor Christopher Markle for his stimulating insights and criticism throughout the production of Red Noses. Special recognition goes to Dr. George W. Sorensen for recmiting me to Texas Tech University. This thesis would not have been possible without his patience and unwavering commitment to this project. I would also like to thank the cast of Red Noses for their infinite creativity and energy to the production. Finally, I am gratefiil to my friend and editor Deirdre Pattillo for her inmieasurable support, motivation, and assistance in this thesis writing process. n TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 n. ANALYSIS OF THE THEMES AND APPROACHES IN THE WORK OF PETER BARNES 10 m. PRE-PRODUCTION WORK FOR RED NOSES 26 IV. CREATIVE PROCESS AND PRESENTATION 39 V CONCLUSION 60 BIBLIOGRAPHY 68 m CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During World War n, as Allied forces battled fascism and the annihilation of six million Jews had begun, a joke circulated among European Jews: Two Jews had a plan to assassinate Hitler. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

Vimeo Link for ALL of Bruce Jackson's and Diane

Virtual March 23, 2021 (42:8) Peter Medak: THE RULING CLASS (1972, 154 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the virtual BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to The Ruling Class Zoom link for all Spring 2021 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 Director Peter Medak Writing Peter Barnes wrote the screenplay adaption from his original play. Producers Jules Buck and Jack Hawkins Music John Cameron Cinematography Ken Hodges Editing Ray Lovejoy Carolyn Seymour....Grace Shelley The film was nominated for Best Actor in a Leading Peter Medak (23 December 1937, Budapest). From Role for Peter O’Toole at the 1973 Academy Awards The Film Encyclopedia, 4th Edition. Ephraim Katz and for the Palme d’Or at the 1972 Cannes Film (revised by Fred Klein & Ronald Dean Nolen). Harper Festival. 2001 NY: “Born Dec. 23, 1937, in Budapest. Escaping Hungary following the crushing of the 1956 Cast uprising, he entered the British film industry that same Peter O'Toole.... Jack Arnold Alexander Tancred year as a trainee at AB-Pathe. Following a long Gurney, 14th Earl of Gurney apprenticeship in the sound, editing, and camera Alastair Sim....Bishop Lampton departments, he became an assistant director, then a Arthur Lowe....Daniel Tucker second-unit director on action pictures. -

„Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duisburg-Essen Publications Online „Yours truly, Jack the Ripper” Die interdiskursive Faszinationsfigur eines Serienmörders in Spannungsliteratur und Film Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. phil. im Fach Germanistik am Institut für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen Vorgelegt von Iris Müller (geboren in Dortmund) Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jochen Vogt Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rolf Parr Tag der Disputation: 26. Mai 2014 Inhalt 1. Vorbemerkungen ..................................................................................... 4 1.1 Erkenntnisinteresse .............................................................................. 7 1.2 ‚Jack the Ripper‘ als interdiskursive Faszinationsfigur .......................... 9 1.3 Methodik und Aufbau der Arbeit ......................................................... 11 2. Die kriminalhistorischen Fakten ........................................................... 13 2.1 Quellengrundlage: Wer war ‚Jack the Ripper‘? ................................... 13 2.2 Whitechapel 1888: Der Tatort ............................................................. 14 2.3 Die Morde .......................................................................................... 16 2.3.1 Mary Ann Nichols ................................................................................................ 16 2.3.2 Annie Chapman .................................................................................................. -

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/[14927] Clare Smith Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith University of Wales: Trinity St. David United Kingdom Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8 ISBN 978-1-137-59999-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59999-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938047 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author has/have asserted their right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accor- dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. -

Black Skin, White Masks (Get Political)

Black Skin, White Masks Fanon 00 pre i 4/7/08 14:16:58 <:IEA>I>86A www.plutobooks.com Revolution, Black Skin, Democracy, White Masks Socialism Frantz Fanon Selected Writings Forewords by V.I. Lenin Homi K. Edited by Bhabha and Paul Le Blanc Ziauddin Sardar 9780745328485 9780745327600 Jewish History, The Jewish Religion Communist The Weight Manifesto of Three Karl Marx and Thousand Years Friedrich Engels Israel Shahak Introduction by Forewords by David Harvey Pappe / Mezvinsky/ 9780745328461 Said / Vidal 9780745328409 Theatre of Catching the Oppressed History on Augusto Boal the Wing 9780745328386 Race, Culture and Globalisation A. Sivanandan Foreword by Colin Prescod 9780745328348 Fanon 00 pre ii 4/7/08 14:16:59 black skin whiteit masks FRANTZ FANON Translated by Charles Lam Markmann Forewords by Ziauddin Sardar and Homi K. Bhabha PLUTO PRESS www.plutobooks.com Fanon 00 pre iii 4/7/08 14:17:00 Originally published by Editions de Seuil, France, 1952 as Peau Noire, Masques Blanc First published in the United Kingdom in 1986 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA This new edition published 2008 www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Editions de Seuil 1952 English translation copyright © Grove Press Inc 1967 The right of Homi K. Bhabha and Ziauddin Sardar to be identifi ed as the authors of the forewords to this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 2849 2 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 2848 5 Paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

American Restaurant Culture and the Rise of the Middle Class, 1880-1920

TURNING THE TABLES: AMERICAN RESTAURANT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF THE MIDDLE CLASS, 1880-1920 by Andrew Peter Haley BA, Tufts University, 1991 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1997 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Andrew Peter Haley It was defended on May 26, 2005 and approved by Dr. Paula Baker, History, The Ohio State University Co-Dissertation Director Dr. Donna Gabaccia, History, University of Pittsburgh Co-Dissertation Director Dr. Richard Oestreicher, History, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Carol Stabile, Communications, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Bruce Venarde, History, University of Pittsburgh ii © Andrew Peter Haley iii TURNING THE TABLES: AMERICAN RESTAURANT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF THE MIDDLE CLASS, 1880-1920 Andrew Peter Haley, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation examines changes in restaurant dining during the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era as a means of understanding the growing influence of the middle- class consumer. It is about class, consumption and culture; it is also about food and identity. In the mid-nineteenth century, restaurants served French food prepared by European chefs to elite Americans with aristocratic pretensions. “Turning the Tables” explores the subsequent transformation of aristocratic restaurants into public spaces where the middle classes could feel comfortable dining. Digging deeply into the changes restaurants underwent at the turn of the century, I argue that the struggles over restaurant culture—the battles over the French-language menu, the scientific eating movement, the celebration of cosmopolitan cuisines, the growing acceptance of unescorted women diners, the failed attempts to eliminate tipping—offer evidence that the urban middle class would play a central role in the construction of twentieth-century American culture. -

Jack the Ripper: Hell Blade, Volume 3 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JACK THE RIPPER: HELL BLADE, VOLUME 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Je-Tae Yoo | 192 pages | 08 Jan 2013 | Seven Seas Entertainment | 9781937867065 | English | New York Jack the Ripper: Hell Blade, Volume 3 PDF Book Release dates: French volume 1. Zivot u neposlusnosti i Zivot u poslusnosti PDF. Ripper stories appealed to an international audience. No account yet? Partners MySchool Discovery. He mutilates female prostitutes with extreme brutality. Everything chronological archives Features incl. London, A. Industry Comments. Stone Season 1 Jan 14, 3 comments. Open Preview See a Problem? Driven mad by infernal influence, his true nature is at last revealed! The Ripper is a legless man "strapped onto the shoulders of a midget". Lost your password? Select Parent Grandparent Teacher Kid at heart. Seven Seas 5 Vols - Complete; Digital. Lulu is the personification of sinful Lust who meets her comeuppance when she unwittingly flirts with the Ripper. We've saved something truly strange for the end. Published: January 8, Strangelove , the antagonist is named General Jack D. It is based on Stephen Knight 's conspiracy theory , which accused royalty and freemasons of complicity in the crimes and was popularised by his book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. Hell Blade 5 books. This Also Happened To Me! Aretha Franklin PDF. Hyde, Jack the Ripper must battle a new breed of creature that tests the limits of science. The Preview Guide is full of of this season's latest shows. Conversation Piece PDF. Death Note. Game Reviews Columns incl. Where will our heroine end up is her bar-hopping Alternative title: Hell Blade. -

Adaptation Through Landscape: the Ruling Class

1 Adaptation Through Landscape: The Ruling Class There have been many screen adaptations of literary narratives set on country estates. These films and television programmes frequently place significant emphasis on the estates’ landscape gardens. Invariably, the emphasis is of a different nature from that conferred on landscapes by the source texts. In the adaptation process, landscape scenes are added or elaborated, but they are rarely excised. Interpolation or transformation of landscape seems, therefore, to have often played an intrinsic role in the transition of narrative from page or stage to film. However, the significance of landscape to the adaptation process has largely been neglected. Compared with, say, costume history, on which critics have lavished attention, landscape history is the poor relation of adaptation studies. Since the late 1960s there has been a dramatic rise in the number of country estate screen adaptations shot on location. This tendency raises two connected questions. Firstly, does the location shot make the film more or less naturalistic than its source text? Since naturalism is a construct, we cannot readily assume that a film becomes naturalistic just by featuring an actual landscape. It depends what use the film makes of the landscape. Secondly, theoreticians of medium specificity have contrasted the concreteness of the filmic image with the imaginary breadth allowed readers by a novel. How does filmic representation delimit the associative range of the landscape? How do these associations contribute to the adaptation? Before the landscape garden is depicted on screen, it is already the result of human intervention: it has been sculpted by one or more landscape designers. -

An Action History of British Underground Cinema

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2003 Not Art: An Action History of British Underground Cinema Reekie, Duncan http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1273 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. NOT ART: AN ACTION HISTORY OF BRITISH UNDERGROUND CINEMA by DuRan Reekie A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Falmouth College of Arts August 2003 THESIS CONTAINS CD This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis and no injormntion derived from it mny be published without the author's prior consent. Abstract NOT ART: AN ACTION IDSTORY OF BRITISH UNDERGROUND CINEMA My thesis is both an oppositional history and a (re)definition of British Underground Cinema culture (1959 - 2(02). The historical significance of Underground Cinema has long been ideologically entangled in a mesh of academic typologies and ultra leftist rhetoric, abducting it from those directly involved. The intention of my work is to return definition to the 'object' of study, to write from within. -

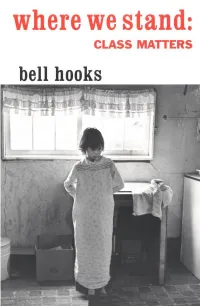

Class Matters

contents preface vii where we stand introduction 1 Class Matters 1 Making the Personal Political 10 Class in the Family 2 Coming to Class Consciousness 24 3 Class and the Politics of Living Simply 38 4 Money Hungry 50 5 The Politics of Greed 63 6 Being Rich 70 7 The Me-Me Class 80 The Young and the Ruthless 8 Class and Race 89 The New Black Elite 9 Feminism and Class Power 101 10 White Poverty 111 The Politics of Invisibility 11 Solidarity with the Poor 121 12 Class Claims 131 Real Estate Racism 13 Crossing Class Boundaries 142 14 Living without Class Hierarchy 156 preface where we stand Nowadays it is fashionable to talk about race or gender; the uncool subject is class. It’s the subject that makes us all tense, nervous, uncertain about where we stand. In less than twenty years our nation has become a place where the rich truly rule. At one time wealth afforded prestige and power, but the wealthy alone did not determine our nation’s values. While greed has always been a part of American capitalism, it is only recently that it has set the standard for how we live and interact in everyday life. Many citizens of this nation, myself included, have been and are afraid to think about class. Affluent liberals concerned with the plight of the poor and dispossessed are daily mocked and ridiculed. They are blamed for all the problems of the welfare state. Caring and sharing have come to be seen as traits of the idealistic weak.