Polyembryonic Development: Insect Pattern Formation in a Cellularized Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

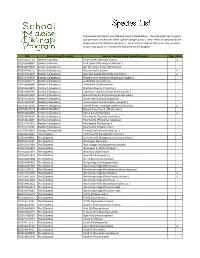

FSMTP Individual Species Lists Final VB.Xlsx

The species collected in your Malaise trap are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. ‘New’ refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in your trap out of all 21 that were deployed for the program. BIN Group (scientific name) Species common name (scientific name) New Rare BOLD:AAE0114 Spiders (Araneae) Pirate spider (Mimetus notius ) ✓ BOLD:AAA8847 Spiders (Araneae) Crab spider (Misumessus oblongus ) BOLD:AAH2753 Beetles (Coleoptera) Ant‐like flower beetle (Anthicidae) BOLD:AAH0141 Beetles (Coleoptera) Ground beetle (Lebia ) ✓ BOLD:AAD4097 Beetles (Coleoptera) Bean leaf beetle (Cerotoma trifurcata ) ✓ BOLD:AAD4999 Beetles (Coleo(Coleoptera)ptera)Western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virvirgiferagifera ) BOLD:AAN6151 Beetles (Coleoptera) Leaf beetle (Longitarsus ) BOLD:ABA9949 Beetles (Coleoptera) Leaf beetle (Chaetocnema ) BOLD:AAU6970 Beetles (Coleoptera) Checkered beetle (Enoclerus ) BOLD:AAB5640 Beetles (Coleoptera) Halloween lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis ) BOLD:AAD7604 Beetles (Coleoptera) Spotted lady beetle (Coleomegilla maculata ) BOLD:AAH0130 Beetles (Coleoptera) Clover weevil (Sitona hispidulus ) BOLD:ABA6367 Beetles (Coleoptera) Plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar ) BOLD:ACD4236 Beetles (Coleoptera) Minute brown scavenger beetle (Corticarina ) ✓ BOLDBOLD:AAH AAH01340134 BeetlesBeetles (Coleoptera)(Coleoptera) ShiningShining floflower er beetlebeetle (Phalacridae)(Phalacridae) BOLD:AAN6202 Beetles -

Topic: Apomixis - Definition and Types

Course Teacher: Dr. Rupendra Kumar Jhade, JNKVV, College of Horticulture,Chhindwara(M.P.) B.Sc.(Hons) Horticulture- 1st Year, II Semester 2019-20 Course: Plant Propagation and Nursery Management Lecture No. 12 Topic: Apomixis - Definition and types Apomixis, derived from two Greek word “APO” (away from) and “MIXIS” (act of mixing or mingling). The first discovery of this phenomenon is credited to Leuwen hock as early as 1719 in Citrus seeds. In apomixes, seeds are formed but the embryos develop without fertilization. The genotype of the embryo and resulting plant will be the same as the seed parent. Definition: “The process of development of diploid embryos without fertilization.” Or “Apomixis is a form of asexual reproduction that occurs via seeds, in which embryos develop without fertilization.” Or “Apomixis is a type of reproduction in which sexual organs of related structures take part but seeds are formed without union of gametes.” In some species of plants, an embryo develops from the diploid cells of the seed and not as a result of fertilization between ovule and pollen. This type of reproduction is known as apomixis and the seedlings produced in this manner are known as apomicts. Apomictic seedlings are identical to mother plant and similar to plants raised by other vegetative means, because such plants have the same genetic make-up as that of the mother plant. Such seedlings are completely free from viruses. In apomictic species, sexual reproduction is either suppressed or absent. When sexual reproduction also occurs, the apomixes is termed as facultative apomixis. But when sexual reproduction is absent, it is referred to as obligate apomixis. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Cross-Compatibility, Graft-Compatibility, and Phylogenetic Relationships in the Aurantioi

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Cross-Compatibility, Graft-Compatibility, and Phylogenetic Relationships in the Aurantioideae: New Data From the Balsamocitrinae A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Plant Biology by Toni J Siebert Wooldridge December 2016 Thesis committee: Dr. Norman C. Ellstrand, Chairperson Dr. Timothy J. Close Dr. Robert R. Krueger The Thesis of Toni J Siebert Wooldridge is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have been an integral part of my research and supportive throughout my graduate studies: A huge thank you to Dr. Norman Ellstrand as my major professor and graduate advisor, and to my supervisor, Dr. Tracy Kahn, who helped influence my decision to go back to graduate school while allowing me to continue my full-time employment with the UC Riverside Citrus Variety Collection. Norm and Tracy, my UCR parents, provided such amazing enthusiasm, guidance and friendship while I was working, going to school and caring for my growing family. Their support was critical and I could not have done this without them. My committee members, Dr. Timothy Close and Dr. Robert Krueger for their valuable advice, feedback and suggestions. Robert Krueger for mentoring me over the past twelve years. He was the first person I met at UCR and his willingness to help expand my knowledge base on Citrus varieties has been a generous gift. He is also an amazing friend. Tim Williams for teaching me everything I know about breeding Citrus and without whom I'd have never discovered my love for the art. -

Cabbage Looper, Trichoplusia Ni (Hübner) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)1 John L

EENY-116 Cabbage Looper, Trichoplusia ni (Hübner) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution stages. In Florida, continuous activity and reproduction occur only south of Orlando. The remainder of Florida and The cabbage looper is found throughout much of the world the portion of Georgia south of Byron, as well as southeast where crucifers are cultivated, and during the summer South Carolina, have intermittent adult activity during the months can be found throughout most of the USA. How- winter months, depending on weather.All points north of ever, overwintering in the US apparently occurs only in the this have no winter activity. southernmost states. It is somewhat erratic in occurrence, typically very abundant one year, and then scarce for two Egg to three years. This is likely due to the residual effects of Cabbage looper eggs are hemispherical in shape, with a nuclear polyhedrosis virus, which is quite lethal to this the flat side affixed to foliage. They are deposited singly insect. The cabbage looper is highly dispersive, and adults on either the upper or lower surface of the leaf, although have sometimes been found at high altitudes and far from clusters of six to seven eggs are not uncommon. The eggs shore. Flight ranges of approximately 200 km have been are yellowish white or greenish in color, bear longitudinal estimated. ridges, and measure about 0.6 mm in diameter and 0.4 mm in height. Eggs hatch in about two, three, and five days at Description and Life Cycle 32, 27, and 20°C, respectively, but require nearly 10 days at The number of generations completed per year varies from 15°C (Jackson et al. -

Polyembryony

COMPILED AND CIRCULATED BY DR. PRITHWI GHOSH, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY, NARAJOLE RAJ COLLEGE Polyembryony [Introduction; Classification; Causes and applications] As per the name Polyembryony – it refers to the development of many embryos. • Occurrence of more than one embryo in a seed is called polyembryony. • When two or more than two embryos develop from a single fertilized egg, then this phenomenon is known as Polyembryony. • In the case of humans, it results in forming two identical twins. This phenomenon is found both in plants and animals. • The best example of Polyembryony in the animal kingdom is the nine-banded armadillo. It is a medium-sized mammal found in certain parts of America and this wild species gives birth to identical quadruplets. Polyembryony in Plants • The production of two or more than two embryos from a single seed or fertilized egg is termed as Polyembryony. • In plants, this phenomenon is caused either due to the fertilization of one or more than one embryonic sac or due to the origination of embryos outside of the embryonic sac. • This natural phenomenon was first discovered in the year 1719 by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in Citrus plant seeds. Types of Polyembryony BOTANY: SEM-V, PAPER-C11T: REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF ANGIOSPERMS, UNITS 7: POLYEMBRYONY AND APOMIXIS COMPILED AND CIRCULATED BY DR. PRITHWI GHOSH, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY, NARAJOLE RAJ COLLEGE There are two different types of polyembryony: 1. Induced Polyembryony – experimentally induced 2. Spontaneous Polyembryony – naturally occurring According to Webber, polyembryony is classified into three different types: 1. Cleavage Polyembryony: In the case of this type, a single fertilized egg gives rise to a number of embryos. -

The Zebra Longwing Butterfly

A Special Visitor to West Central Louisiana and Almost Eden: The Zebra Longwing Butterfly For the first time this past fall we were graced with the presence of Zebra Longwing Butterflies, Heliconius charithonia. These big bold beautiful butterflies are ‘sometimes visitors’ to the warm southern and more tropical regions of Louisiana and are permanent residents of Florida (their state butterfly) and the Lower Rio Grande Valley of south Texas. They migrate north to other portions of the US and have been reported from as far north as Illinois, Colorado, Virginia, and even New York (you think they could have shown up a little sooner, lol). They were here from October until mid-December of 2016. This is one of the easiest butterflies to recognize and of the first a budding butterfly enthusiast like myself to have learned and one I had always yearned to see. Their long delicate wings and seemingly non-stop fluttering give rise to a fairy-like appearance. The long dark wings with broad bold wide buttery yellow stripes are actually warning signs to predators that this butterfly is poisonous due to the fact that the caterpillars consume Passionvines which have poisonous components that the insects take up as a defense against predation in the same way the Monarch butterfly does. The Zebra Longwing is reported to have spatial memory and will return to the same plants each day in search of nectar. And like the Julia, they also have an especially strong affinity for the flowers of Lantana but are not against visiting other similarly nectar rich species such as Porterweed, Mexican Firebush, and Pentas. -

Sensory Gene Identification in the Transcriptome of the Ectoparasitoid

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Sensory gene identifcation in the transcriptome of the ectoparasitoid Quadrastichus mendeli Zong‑You Huang, Xiao‑Yun Wang, Wen Lu & Xia‑Lin Zheng* Sensory genes play a key role in the host location of parasitoids. To date, the sensory genes that regulate parasitoids to locate gall‑inducing insects have not been uncovered. An obligate ectoparasitoid, Quadrastichus mendeli Kim & La Salle (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae: Tetrastichinae), is one of the most important parasitoids of Leptocybe invasa, which is a global gall‑making pest in eucalyptus plantations. Interestingly, Q. mendeli can precisely locate the larva of L. invasa, which induces tumor‑like growth on the eucalyptus leaves and stems. Therefore, Q. mendeli–L. invasa provides an ideal system to study the way that parasitoids use sensory genes in gall‑making pests. In this study, we present the transcriptome of Q. mendeli using high‑throughput sequencing. In total, 31,820 transcripts were obtained and assembled into 26,925 unigenes in Q. mendeli. Then, the major sensory genes were identifed, and phylogenetic analyses were performed with these genes from Q. mendeli and other model insect species. Three chemosensory proteins (CSPs), 10 gustatory receptors (GRs), 21 ionotropic receptors (IRs), 58 odorant binding proteins (OBPs), 30 odorant receptors (ORs) and 2 sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs) were identifed in Q. mendeli by bioinformatics analysis. Our report is the frst to obtain abundant biological information on the transcriptome of Q. mendeli that provided valuable information regarding the molecular basis of Q. mendeli perception, and it may help to understand the host location of parasitoids of gall‑making pests. -

E0020 Common Beneficial Arthropods Found in Field Crops

Common Beneficial Arthropods Found in Field Crops There are hundreds of species of insects and spi- mon in fields that have not been sprayed for ders that attack arthropod pests found in cotton, pests. When scouting, be aware that assassin bugs corn, soybeans, and other field crops. This publi- can deliver a painful bite. cation presents a few common and representative examples. With few exceptions, these beneficial Description and Biology arthropods are native and common in the south- The most common species of assassin bugs ern United States. The cumulative value of insect found in row crops (e.g., Zelus species) are one- predators and parasitoids should not be underes- half to three-fourths of an inch long and have an timated, and this publication does not address elongate head that is often cocked slightly important diseases that also attack insect and upward. A long beak originates from the front of mite pests. Without biological control, many pest the head and curves under the body. Most range populations would routinely reach epidemic lev- in color from light brownish-green to dark els in field crops. Insecticide applications typical- brown. Periodically, the adult female lays cylin- ly reduce populations of beneficial insects, often drical brown eggs in clusters. Nymphs are wing- resulting in secondary pest outbreaks. For this less and smaller than adults but otherwise simi- reason, you should use insecticides only when lar in appearance. Assassin bugs can easily be pest populations cannot be controlled with natu- confused with damsel bugs, but damsel bugs are ral and biological control agents. -

Cervecera. Areas Sembradas Y Graduados, Facultades Y Empresas, Producción En Los Últimos Dos Decenios

ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA Y VETERINARIA ANALES TOMO XLVI 1992 BUENOS AIRES REPUBLICA ARGENTINA ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA Y VETERINARIA Fundada el 16 de Octubre de 1909 Avenida Alvear 1711, 2Q P., Tel. /Fax: 812-4168 C.P. 1014, Buenos Aires, República Argentina MESA DIRECTIVA Presidente Dr. Norberto Ras Vicepresidente Ing. Agr. Diego J. Ibarbia Secretario General Dr. Alberto E. Cano Secretario de Actas Ing. Agr. Manuel V. Fernández Valiela Tesorero Dr. Jorge Borsella Protesorero ACADEMICOS DE NUMERO Dr. Héctor G. Aramburu A rq. Pablo Hary Ing. Agr. Héctor O. Arriaga Ing. Agr.Juan H. Hunziker Ing. Agr. Wilfredo H. Barrett Ing. Agr.Diego J. Ibarbia Dr. Jorge Borsella Ing. Agr.Walter F. Kugler Dr. Raúl Buide Dr. Alfredo Manzullo Ing. Agr. Juan J. Burgos Ing. Agr.Angel Marzocca Dr. Angel L. Cabrera Ing. Agr.Edgardo R. Montaldi Dr. Alberto E. Cano Dr. Emilio G. Morini Dr. Bernardo J. Carrillo Dr. Rodolfo M. Perotti Dr. Pedro Cattáneo +Ing. Agr.Arturo E. Ragonese Ing. Agr. Milán J. Dimitri Dr Norberto Ras t Ing. Agr. Ewald Favret Ing. Agr.Manfredo A.L. Reichart Ing. Agr. Manuel V. Fernández Valiela Ing. Agr.Norberto A.R. Reichart Dr. Guillermo G. Gallo Ing. Agr.Luis De Santis Dr. Enrique García Mata Ing. Agr.Alberto Soriano Ing. Agr. Rafael García Mata Dr. Ezequiel C. Tagle Ing. Agr. Roberto E. Halbinger Ing. Agr.Esteban A. Takacs ACADEMICOS HONORARIOS Ing. Agr. Dr. Norman E. Borlaug (Estados Unidos) Ing. Agr. Dr. Theodore Schultz (Estados Unidos) ACADEMICOS CORRESPONDIENTES Ing. Agr. Ruy Barbosa Ing. Agr. Jorge A. Mariotti (Chile) (Argentina) Dr. -

Spiteful Soldiers and Sex Ratio Conflict in Polyembryonic

vol. 169, no. 4 the american naturalist april 2007 Spiteful Soldiers and Sex Ratio Conflict in Polyembryonic Parasitoid Wasps Andy Gardner,1,2,* Ian C. W. Hardy,3 Peter D. Taylor,1 and Stuart A. West4 1. Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada; Behaviors that reduce the fitness of the actor pose a prob- 2. Department of Biology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario lem for evolutionary theory. Hamilton’s (1963, 1964) in- K7L 3N6, Canada; clusive fitness theory provides an explanation for such 3. School of Biosciences, University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington Campus, Loughborough LE12 5RD, United Kingdom; behaviors by showing that they can be favored because of 4. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, School of Biological Sciences, their effects on relatives. This is encapsulated by Hamil- University of Edinburgh, King’s Buildings, Edinburgh EH9 3JT, ton’s (1963, 1964) rule, which states that a behavior will United Kingdom be favored when rb 1 c, where c is the fitness cost to the actor, b is the fitness benefit to the recipient, and r is their Submitted September 15, 2006; Accepted November 7, 2006; genetic relatedness. Hamilton’s rule provides an expla- Electronically published February 5, 2007 nation for altruistic behaviors, which give a benefit to the recipient (b 1 0) and a cost to the actor (c 1 0): altruism is favored if relatedness is sufficiently positive (r 1 0) so that rb Ϫ c 1 0. The idea here is that by helping a close abstract: The existence of spiteful behaviors remains controversial. -

Chalcid Forum Chalcid Forum

ChalcidChalcid ForumForum A Forum to Promote Communication Among Chalcid Workers Volume 23. February 2001 Edited by: Michael E. Schauff, E. E. Grissell, Tami Carlow, & Michael Gates Systematic Entomology Lab., USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History Washington, D.C. 20560-0168 http://www.sel.barc.usda.gov (see Research and Documents) minutes as she paced up and down B. sarothroides stems Editor's Notes (both living and partially dead) antennating as she pro- gressed. Every 20-30 seconds, she would briefly pause to Welcome to the 23rd edition of Chalcid Forum. raise then lower her body, the chalcidoid analog of a push- This issue's masthead is Perissocentrus striatululus up. Upon approaching the branch tips, 1-2 resident males would approach and hover in the vicinity of the female. created by Natalia Florenskaya. This issue is also Unfortunately, no pre-copulatory or copulatory behaviors available on the Systematic Ent. Lab. web site at: were observed. Naturally, the female wound up leaving http://www.sel.barc.usda.gov. We also now have with me. available all the past issues of Chalcid Forum avail- The second behavior observed took place at Harshaw able as PDF documents. Check it out!! Creek, ~7 miles southeast of Patagonia in 1999. Jeremiah George (a lepidopterist, but don't hold that against him) and I pulled off in our favorite camping site near the Research News intersection of FR 139 and FR 58 and began sweeping. I knew that this area was productive for the large and Michael W. Gates brilliant green-blue O. tolteca, a parasitoid of Pheidole vasleti Wheeler (Formicidae) brood. -

Introduced and Native Leafrollers (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) on Berry Crops in the Lower Fraser Valley, B

INTRODUCED AND NATIVE LIZAFROLLERS (LEPIDOPTERA : TORTRICIDAE) ON BERRY CROPS IN THE LOWER FRASER VALLEY, B .C. David Roy ~illespie B .Sc,, Simon Fraser University, 1975 M~SC.,Simon Fraser university, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMFNTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Biological Sciences @ David Roy Gillespie 1981 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December 1981 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Approval Name : David R. Gillespie Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Introduced and native leafrollers (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) on berry crops in the Lower Fraser Valley, B. C. Examining Committee Chairman: Dr. Robert C. Brooke Dr. B. P. B'ehne, Senior Supervisor Dr. J. H. Borden ~f.J. Raine Dr. P. Belton, Public Examiner ~r:stanlei G.-- oyt, ~ntomolo~ist,Tree Fruit Research, Hentre, Washington State University, Washington, U.S.A. External Examiner Date approved: 9L- &. /%Y ----PART IAt- COPYR l GHT L I CENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title sf which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a reqbest from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies.