Aemi Journal • Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tove Kjellmark Born 1977 Based in Stockholm, Sweden

Tove Kjellmark Born 1977 Based in Stockholm, Sweden P. +46 (0)73 622 77 51 M. [email protected] W. www.tovekjellmark.com S. Wip:sthlm Årsta Skolgränd 12 B 117 43 Stockholm CV 1/2 Tove Kjellmark +46(0)736227751 [email protected] EDUCATION 2016 The Imitation Game, 12.02.2016-05.06.2016 2014 Introduction to artistic research at Konstfack; at Manchester Art Gallery University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm Promises of Monsters, 28.04.2016-29.04.2016 2003-2009 Master of fine Arts at The Royal Institute of Art, University of Stavanger, Norway Stockholm 2001-2003 Idun Lovén School of Arts, sculptur, Stockholm 2015 SKULPTUR, 04.02.2015-15.05.2015 1999-2000 Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Perpignan, France Royal British Society of Sculptors in London Och vad är frågan?/And what is the question? SOLO SHOWS 05.09.2015 - 15.11.2015 Bohusläns Museeum, Uddevalla 2018 Human Assemblage, 1.11.2018-11.11.2018 2014 New Dimensions, 07.06.2014-22.08.2014 WIP Konsthall, Stockholm Galleri Andersson/Sandström in collaboration with 2018 Another Nature, 17.10.2018-10.11.2018 Umeå2014 European capital of culture Moore contemporary, Perth, Austrailia We don’t have to take our clothes off 2017 Inside, 06.11.2017-03.12.2017 02.03.2014 - 31.03.2014 Verkstad Konsthall, Norrköping Geijutsu Kouminkan,Tokyo 2017 Inside, 07.05.2017-30.06.2017 Katarina Church, Stockholm 2013 Going Dark, 26.09.2013-28.09.2013 2015 Alone Together, 24.11.2015-11.12.2015 LEAP, Lab for Electronic Arts and Performance Berlin Epicenter, Stockholm ABCDEFGHI 20.04.2013-28.07.2013 -

Special List 390: Italian Authors, Language, Imprints and Subjects

special list 390 1 RICHARD C.RAMER Special List 390 Italian Authors, Language Imprints and Subjects 2 RICHARDrichard c. C.RAMER ramer Old and Rare Books 225 east 70th street . suite 12f . new york, n.y. 10021-5217 Email [email protected] . Website www.livroraro.com Telephones (212) 737 0222 and 737 0223 Fax (212) 288 4169 October 26, 2020 Special List 390 Italian Authors, Language Imprints and Subjects Items marked with an asterisk (*) will be shipped from Lisbon. SATISFACTION GUARANTEED: All items are understood to be on approval, and may be returned within a reasonable time for any reason whatsoever. VISITORS BY APPOINTMENT special list 390 3 Special List 390 Italian Authors, Language Imprints and Subjects How a Gentleman Should Not Behave 1. ALDANA, Cosme de. Discorso contro il volgo in cui con buone ragioni si reprovano molte sue false opinioni …. Florence: Giorgio Marescotti, 1578. 8°, eighteenth-century sheep (minor worm damage to front cover), spine with raised bands in four compartments, minimal gilt decoration, citron leather lettering piece in second compartment from head (slight defects), gilt letter, text-block edges sprinkled red. Woodcut devices of Marescotti on title-page and colophon leaf. Text in italic. Woodcut initials, headpieces, and tailpieces. Typographical headpiece. Italic type. Minor stains on title and in preliminary leaves. Final line on title page cropped. Overall in very good condition. Contemporary or early ink inscription at top of **1 (the beginning of the table of contents): “Conceptus sacados de la obra y tabla.” Old ink inscription in lower blank margin of title page shaved. (31, 1 blank ll.), 442 pp., (2 ll.). -

Explorations in Sights and Sounds

Number 2 Summer, 1982 EXPLORATIONS IN SIGHTS AND SOUNDS Annual Review Supplement to Explorations in Ethnic Studies Published by NAIES Ethnic Studies Department California State Polytechnic University 3801 West Temple Avenue Pomona, California 91768 EDITOR: Charles C. Irby California State Polytechnic University ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Gretchen Bataille Iowa State University Helen Maclam Dartmouth College ASSISTANT EDITOR: Meredith Reinhart California State Polytechnic University ii. EXPLORATIONS IN SIGHTS AND SOUNDS Number 2 - Summer, 1982 CONTENTS James A. Banks , Multiethnic Education: Theory and Practice, reviewed by Ramond L. Hall ...................................1 Hubert M. Blalock , Jr., Race and Ethnic Relations, reviewed by Hardy T. Frye .......................................................3 Hedu Bouraoui , ed., The Canadian Alternative: Cultural Pluralism and Canadian Unity, reviewed by George F. Theriault ...............5 Lynwood Carranco and Estle Beard , Genocide and Vendetta: The Indian Wars of Northern California reviewed by Charles E. Roberts .............................................6 John F. Day , Bloody Ground, reviewed by Helen G. :::hapin ......8 William A. Doublass and Richard W. Etulain , eds., Basque Americans: A Guide to Information Sources, reviewed by Sergio D. Elizondo ...........................................10 Walter Dyke and Ruth Dyk , eds., Left Handed: A Navajo Autobiography, reviewed by Andrew Wiget ...................11 Alice Eichholz and James M. Rose , eds., Free Black Heads of Household in the New -

Sofia Kyrka Sofia Church

NORDIC EDITION • SEPTEMBER 6–9, 2018 • NORDIC EDITION Svend-Ove Møller Orgel- Te Deum (1949) Sofia kyrka 1903-1949 Sofia Church J. P. E. Hartmann Sonate i g-mol, op. 58 (1855) 1805-1900 1. Allegro marcato 2. Andantino Torsdag 6 september kl 19.30 3. Allegro poco agitato Thursday September 6th, 7.30 p.m. César Franck Prière, op. 20 (1860) 1822-1890 Denmark Christian Præstholm 3 koralforspil til Den Danske Salmebog: 1972- • Alt hvad som fuglevinger fik Kristian Krogsøe, orgel (Mel: Th. Laub) • Min Jesus, lad mit hjerte få (Mel: Carl Nielsen) • Denne er dagen, som Herren har gjort (Mel: Melchior Vulpius/Laub) Maurice Duruflé Scherzo, op. 2 (1926) 1902-1986 Jeanne Demessieux Te Deum, op. 11 (1957-58) 1921-1986 Mingel efter konserten, ingen föranmälan behövs. Welcome to a mingle after the concert. 2 ORGANSPACE |2018 Kristian Krogsøe Kristian Krogsøe (b. 1982) has been the Spring 2012 his first CD was released with Aarhus Cathedral organist since 2007 and the complete organ works by Duruflé and teaches the organ at the Royal Academy of his Requiem and Motets together with Music in Aarhus. Aarhus Cathedral Choir and featuring Bo Skovhus and Randi Stene. The recording He studied with prof. Ulrik Spang-Hanssen has recently won the german critics’ award at the Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus “Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik”. and later on, he studied with prof. Leo van Doeselaar and Erwin Wiersinga at the Kristian has also appeared as a soloist with Soloists Class at the University of Arts in orchestras. In the year 2008 he played the Berlin, Germany. -

SOMIGLIANZE E RAPPORTI TRA NAPOLI E IL PORTOGALLO (Sumigliànz E Rappòrt Tra Napule E O’ Portuàll )

SOMIGLIANZE E RAPPORTI TRA NAPOLI E IL PORTOGALLO (Sumigliànz e rappòrt tra Napule e o’ Portuàll ) SEMELHANÇAS E RELAÇÕES ENTRE NÁPOLES E PORTUGAL RESEMBLANCES AND RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NAPLES AND PORTUGAL Jorge Silva 2012 INDICE/ÍNDICE/INDEX Ringraziamenti/Agradecimentos/Acknowledgements 3 Introduzione/Introdução/Introduction 5 Citazioni/Citações/Quotes 9 OSSERVAZIONI GENERALI / GENERALIDADES Geografia e Clima 11 Lingua e Popolo/Língua e Povo 11 RAPPORTI STORICI/RELAÇÕES HISTÓRICAS Una Storia Comune/Uma História Comum 13 Matrimoni Reali e Parentela/Casamentos Reais e Parentescos 23 Santi, Mercanti, Ecclesiastici e Artisti 25 Santos, Mercadores, Eclesiásticos e Artistas 26 Dopo l’Unità d’Italia/Depois da Unificação da Itália 30 ILLUSTRAZIONI/FIGURAS/PICTURES 32 RESEMBLANCES AND RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PORTUGAL AND NAPLES (English Text) Geography and Weather 43 Language and People 43 A Common History 44 Royal Weddings and Family Ties 49 Saints, Merchants, Clergymen and Artists 50 After the Unification of Italy 52 CONCLUSIONE/CONCLUSÃO/CONCLUSION 53 1 BIBLIOGRAFIA/BIBLIOGRAPHY 57 DOCUMENTI/DOCUMENTOS/DOCUMENTS 58 NAPOLI, TI ODIO! (poesia) 59 NÁPOLES, ODEIO-TE! (poema) 60 NAPLES, I HATE YOU! (poem) 61 “FARE IL PORTOGHESE”/”FAZER-SE DE PORTUGUÊS”/ ”TO ACT LIKE A PORTUGUESE” 63 COLTIVANDO QUEST’AMICIZIA/CULTIVANDO ESTA AMIZADE /CHERISHING THIS FRIENDSHIP Associazione Italia-Portogallo 65 Amicizia Napoli-Portogallo 67 ABBREVIAZIONI E ACRONIMI/SIGLAS E ABREVIATURAS/ ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 69 INDICE ICONOGRAFICO/ÍNDICE ICONOGRÁFICO/ ICONOGRAPHIC -

Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1047-2932 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Robert Laxalt: A Basque Who Wrote SPRING by David Río “I am not a Basque scholar or even a Basque In a Hundred Graves: A Basque Portrait 2001 writer; I am just a Basque who writes.” In (1972), A Time We Knew: Images of this humble way Robert Laxalt used to Yesterday in the Basque Homeland (1990) or define himself whenever asked about his The Land of My Fathers: A Son’s Return to role in the expansion of Basque studies in the Basque Country (1999), and also in the NUMBER 63 the United States or about his literary contributions to Basque culture. This extreme humility was one of the features that most struck In this issue: me about Bob Laxalt when I first interviewed him in the spring of 1995. At that time I was familiar Robert Laxalt 1 with his impressive literary career and admired him for his imagina- tive writings on the Basques. In the Highlights 3 following years, until our last meeting in September 2000, I had Advisory Board Meeting 4 the pleasure to visit Bob almost every summer and to discover his deep humanity. Over time, my Basque Art Exhibition 5 admiration for Bob Laxalt’s literary gift was equalled by my high respect for his remarkable human Photo: John Ries UN Press Celebrates values. 40th Anniversary 6 novella A Cup of Tea in Pamplona (1985). In During these long interviews with Bob fact, Robert Laxalt may be regarded as the Laxalt I was primarily interested in his most talented American author writing on Studies Abroad in Basque roots and, above all, in his creative the experience of Basques both in America the Basque Country 7 writings on the Basques. -

The Best Sheepherder. the Racial Stereotype of Basque Immigrants in the American West Between the End of the Nineteenth and the Beginning of the Twentieth Centuries

Historia Contemporánea 56: 81-119 ISSN: 1130-2402 — e-ISSN: 2340-0277 DOI: 10.1387/hc.17458 THE BEST SHEEPHERDER. THE RACIAL STEREOTYPE OF BASQUE IMMIGRANTS IN THE AMERICAN WEST BETWEEN THE END OF THE NINETEENTH AND THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURIES THE BEST SHEEPHERDER. EL ESTEREOTIPO RACIAL DE LOS INMIGRANTES VASCOS EN EL OESTE NORTEAMERICANO ENTRE FINALES DEL SIGLO XIX Y PRINCIPIOS DEL XX Iker Saitua University of California, Riverside and University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) orcid.org/0000-0002-8367-7070 Recibido el 15-12-2016 y aceptado el 12-7-2017 Resumen: El presente artículo estudia la imagen de los inmigrantes vascos en el Oeste norteamericano entre finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, y la influencia que esa imagen tuvo en la integración socioeconómica de este colec- tivo, dedicado fundamentalmente al pastoreo de ovejas, prestando especial aten- ción al Estado de Nevada. Su objetivo principal es mostrar cómo dicha imagen fue racializada, cómo la etiqueta étnica de vasco fue equiparada a la categoría racial «blanca» en los Estados Unidos, especialmente tras la aprobación de la ley de inmigración de 1924, y cómo esta percepción benefició a los inmigran- tes vascos, facilitando su integración. Para ello examina los estudios historio- gráficos, sociológicos y antropológicos sobre los inmigrantes vascos en el Oeste realizados a finales del siglo XIX y principios del siglo XX por intelectuales esta- dounidenses, y muestra cómo, influidos por el análisis turneriano y la ideología racialista de la época, elaboraron un estereotipo racial vasco, expresado en la imagen del «buen pastor», que terminó reflejándose en la prensa escrita estado- unidense y divulgándose a través de ella. -

Basques in the Americas from 1492 To1892: a Chronology

Basques in the Americas From 1492 to1892: A Chronology “Spanish Conquistador” by Frederic Remington Stephen T. Bass Most Recent Addendum: May 2010 FOREWORD The Basques have been a successful minority for centuries, keeping their unique culture, physiology and language alive and distinct longer than any other Western European population. In addition, outside of the Basque homeland, their efforts in the development of the New World were instrumental in helping make the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America what they are today. Most history books, however, have generally referred to these early Basque adventurers either as Spanish or French. Rarely was the term “Basque” used to identify these pioneers. Recently, interested scholars have been much more definitive in their descriptions of the origins of these Argonauts. They have identified Basque fishermen, sailors, explorers, soldiers of fortune, settlers, clergymen, frontiersmen and politicians who were involved in the discovery and development of the Americas from before Columbus’ first voyage through colonization and beyond. This also includes generations of men and women of Basque descent born in these new lands. As examples, we now know that the first map to ever show the Americas was drawn by a Basque and that the first Thanksgiving meal shared in what was to become the United States was actually done so by Basques 25 years before the Pilgrims. We also now recognize that many familiar cities and features in the New World were named by early Basques. These facts and others are shared on the following pages in a chronological review of some, but by no means all, of the involvement and accomplishments of Basques in the exploration, development and settlement of the Americas. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface......................................................................................... -

Collaboration of Interreligious Workers and the Perception of Help Seekers in Interreligious Organizations

Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University Department of Social Sciences Master’s program in voluntary social work with focus on organizational analysis and development in civil society, 120 university credits Collaboration of interreligious workers and the perception of help seekers in interreligious organizations. Christabel Hellberg Degree project in voluntary social work at advanced level, 30 university credits Course: SM40, D thesis, Master's degree Supervisor: Johan von Essen Examiner: Lars Sörnsen Acknowledgement Foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to all those who participated in my research. I would not have been given the opportunity to do this research without your participation. Secondly, I would like to take this opportunity to thank my supervisor Johan Von Essen, professor, researcher and lecturer at Ersta Sköndal Bräcke Högskola for your generosity, support and guidance. I would like to thank Hanna Berg for your plentiful support and encouragement. Furthermore, I would like to thank Johan Gärde, lecture and docent at Ersta Sköndal Bräcke Högskola for your support and guidance. Last but not least I would like to thank my family starting with my niece Patricia Kamwela for your abundant support; my husband Robert Hellberg and my son Nils Hellberg for your generosity, support, and understanding; my parents-in-law Evy Hellberg and Ingvar Hellberg, who made it possible for me to attend the Swedish language classes by taking care of my son; my late mother Grace Mwania and my daddy Joseph Mwania Manyenze, who supported gender equality and made it possible for me to attend secondary school which wasn’t possible for many girls in my home village. -

Uma Tiara Com 4000 Diamantes

Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes A tiara with 4000 diamonds História e paradeiro da tiara de D. Estefânia, reconvertida por D. Maria Pia e vendida após a implantação da República. 1858-1912 João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes História e paradeiro da tiara de D. Estefânia, reconvertida por D. Maria Pia e vendida após a implantação da República. 1858-1912 João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Título: Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes. História e paradeiro da tiara de D. Estefânia, reconvertida por D. Maria Pia e vendida após a implantação da República. 1858-1912 Aos meus pais, por me ensinarem a ver. Autor: João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira [email protected] Prefácio: Teresa Maranhas, PNA, DGPC Revisão: Teresa Maranhas, PNA, DGPC Hugo Xavier, PNP, PSML Capa, design e paginação: Nicolás Fabian nfabian.pt Imagem da capa: Desenho do diadema de D. Estefânia, Nicolás Fabian, técnica mista sobre papel, col. autor. Tradução: Autor Revisão da tradução: Catarina Alcântara Luz Abril 2020, Todos os direitos reservados Uma tiara com 4000 diamantes João Júlio Rumsey Teixeira Índice 7 9 15 Prefácio Introdução Identificação e Análise Pericial 21 37 39 História, Conclusão Apêndice Proveniência Documental e Autorias Abreviaturas ANTT - Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo APNA - Arquivo do Palácio Nacional da Ajuda Col. - Coleção 55 57 58 Cx. - Caixa DGFP - Direção Geral da Fazenda Pública Preface Introduction Identification Doc. - Documento and expert Doc. cit. - Documento citado analysis ELI - Espólio Leitão & Irmão FCG - Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian Fig. - Figura 60 67 68 Inv. -

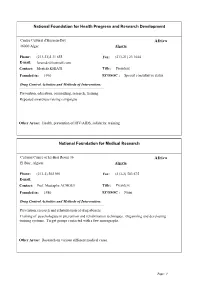

NGO Directory

National Foundation for Health Progress and Research Development Centre Culturel d'Hussein-Day Africa 16000 Alger Algeria Phone: (213-21)2 31 655 Fax: (213-21) 23 1644 E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Mostefa KHIATI Title: President Founded in: 1990 ECOSOC : Special consultative status Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, counselling, research, training Repeated awareness raising campaigns Other Areas: Health, prevention of HIV/AIDS, solidarity, training National Foundation for Medical Research Cultural Centre of El-Biar Room 36 Africa El Biar, Algiers Algeria Phone: (213-2) 502 991 Fax: (213-2) 503 675 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Mustapha ACHOUI Title: President Founded in: 1980 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, research and rehabilitation of drug abusers. Training of psychologists in prevention and rehabilitation techniques. Organizing and developing training systems. Target groups contacted with a few monographs. Other Areas: Research on various different medical cases. Page: 1 Movimento Nacional Vida Livre M.N.V.L. Av. Comandante Valodia No. 283, 2. And.P.24. Africa C.P. 3969 Angola, Rep. Of Luanda Phone: (244-2) 443 887 Fax: E-mail: Contact: Dr. Celestino Samuel Miezi Title: National Director, Professor Founded in: 1989 ECOSOC : Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, treatment, counselling, rehabilitation, training, and criminology To combat drugs and its consequences through specialized psychotherapy and detoxification Other Areas: Health, psychotherapy, ergo therapy Maison Blanche (CERMA) 03 BP 1718 Africa Cotonou Benin Phone: (229) 300850/302816 Fax: (229) 30 04 26 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Rene Gilbert AHYI Title: President Founded in: 1988 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, treatment, training and education.